By Rob Willis

Colonel John F. Hartranft surveyed the blue-jacketed ranks to his front with a mixture of frustration and humiliation, and some of the men returned the favor. It was July 20, 1861, and the entire Federal Army under the command of Irvin McDowell was marching south toward the first, and hopefully last, major battle of the war.

The men of Hartranft’s 4th Pennsylvania would not be going with them, however, because their 90-day enlistments had expired and most of them wanted to go home, at least for a while. Despite speeches, accusations, and even a personal plea from McDowell, the men of the 4th had had enough, and, while many had already reenlisted in new regiments, they felt that the Army had used them badly; they wanted a break. Hartranft turned his back on his regiment and rode south with the rest of the army to volunteer his services to the staff of Colonel William B. Franklin—an act that would win Hartranft the Medal of Honor after the war—while the 4th began its march north to Washington. The next day, July 21, the army would be defeated at the first Battle of Bull Run, and McDowell would lay some of the blame squarely at the feet of the 4th Pennsylvania.

Hartranft was perhaps the classic example of the volunteer officer, having served in his local militia unit before the war started. A former civil engineer and deputy sheriff, the 30-year-old had passed the county bar exam in 1860 and was practicing law in Montgomery County, Penn., when the South seceded. Elected colonel by the militia companies of Montgomery County, Hartranft offered their services to Washington and was soon appointed head of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment. Even before the 4th had turned their backs on the Union that July day, Hartranft realized he might be of further service and, eager to prove himself, asked for and received permission to raise a second regiment. Thus, in mid-September 1861, the first men of the new, three-year 51st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry began arriving at Camp Curtin near Harrisburg to be organized and mustered in.

The men of the 51st were drawn from Montgomery, Northhampton, Centre, Snyder, Union, and Lycoming counties. In fact, many of them had served in the ranks of the old 4th, and had felt driven to clear their reputation after the disaster at Bull Run and McDowell’s indictment.

As the new officers and men of the 51st labored through September and into the late autumn to get the regiment into shape, the rain, their poor campsite, scant clothing, and the indifferent attitude of the U.S. Army were too much for some of the recruits, and desertion became an alarming problem, although one that the regiment would weather successfully.

The hardier souls of the 51st found unofficial ways to improve their lot, and such actions led some observers to look upon the 51st—to the regiment’s apparent delight—as a pack of rascals. Beyond the pedestrian offenses of roughhousing, drunkenness, and generally raucous behavior, one incident stood out in the memories of the men that autumn.

In early November, after suffering through miserable rations for too long, a dozen men slid past the perimeter guard one dark evening and made their way to an Army supply train not far from the camp. They selected a fine, 250-pound hog from the livestock car, killed it, and, slinging it in a blanket, made their way back to camp, envisioning a wonderful meal for their efforts. Unfortunately, they found themselves challenged by a picket but, thinking quickly, proclaimed themselves to be “railroad hands” who had found a sick soldier some distance up the tracks. Feigning grave concern for the “sick fellow,” the men convinced the guard to let them pass, only to run into the camp’s interior guards, who were also in the process of believing the story until the officer of the day approached while on grand rounds. In no time, stories of nonexistent physicians and harmful vapors were invented by the culprits, and the tale was related with such urgency that the OOD was fooled as well. The cargo, borne by its terrified owners, finally returned to the safety of the company street at 1 am.

Winter Drill

On November 5, 1861, Governor Andrew G. Curtin presented new state colors to the 51st, 52nd, and 53rd Pennsylvania in a joint ceremony, and thus gave the 51st Regiment a unique characteristic: Because Colonel Hartranft had preserved the national and regimental colors that the old 4th Pennsylvania had carried and presented them to the 51st as well, the 51st was one of very few Civil War units to carry three flags—two national colors and a blue state flag.

By mid-November the regiment finally received orders to move to Baltimore and, feeling that they owed Harrisburg one last fling, almost half of the 51st broke guard during the evening of November 15, went into town, and proceeded to throw themselves a party. Hartranft, fearing unimagined chaos, ordered what was left of the regiment into town to escort the revelers back to camp under guard. Unfortunately, most of the guards—many of whom were allegedly temperate to begin with—were talked into “just one toast” by the renegades, and before it was all over the rescuers were carried back to camp in a terrible state of intoxication by the rescued.

The 51st moved by rail toward Baltimore and reached Annapolis on November 18. Along the way the boys found time to forage for food that resulted in, among other things, the theft of a watchdog, his chain, and the larder he was supposed to be guarding. Moving outside the city, they took up quarters at Camp Burnside and commenced the dreary job of winter drill. On December 24, the 51st was formally assigned to Brig. Gen. Jesse Reno’s brigade, together with the 51st New York, 21st Massachusetts, and 9th New Jersey. The regiment passed into the new year as part of Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Coast Division; few men realized at the time what that meant.

The 51st Lands in North Carolina

During the first week of January 1862, the regiment was split into halves and boarded Navy transport ships with the rest of Burnside’s command for a grueling, month-long journey down the wintry coast toward destinations unknown.

Scout and Cossack were only two of over 100 vessels that comprised Burnside’s large but inexperienced amphibious force and, as the fleet moved slowly south, it was revealed that its goal was Hatteras Inlet, N.C. Over the next 30 days the men of the regiment suffered horrible conditions on the two ships, including sweeping seasickness (most of the men had never even seen a ship this large, let alone sailed through stormy waters), ship collisions, lack of proper accommodations, and disease. Rations were very short, even absent, for days at a time, and the men resorted to drinking vinegar for several days because the fresh-water supply had run out.

The officers tried to drill the men during calmer moments, but the sound of hundreds of rifle butts thumping on the hurricane deck compelled the ship captains to order such activity to cease, because the sailors couldn’t hear orders over the din. Several soldiers died during the journey despite the efforts of the Navy to provide decent conditions, and by the time the regiment was put ashore on Roanoke Island on February 7, 1862, the soldiers were thoroughly prepared to embrace dry land again, enemy forts be damned. The next morning, Burnside’s force attacked the Confederate positions and forced the surrender of the island, although the 51st was only lightly engaged.

When Roanoke Island was cleared of Confederate troops, the regiment began a miserable occupation. They found occasional distraction harassing the locals, but staying warm and fed was their chief concern. On March 3 the men were delighted to give up their old “pig-iron” rifles for new Enfield rifled muskets, and were simultaneously ordered to pack up and re-board their ships. Conditions afloat were just as bad as before but the duration of the journey was mercifully shorter and, on March 13, 1862, the brigade again reached land.

The Battle of New Bern

They debarked and began marching north toward New Bern, N.C., through “the muddiest mud ever invented,” and made about four miles before their first halt. There they were confronted by a Marine artillery officer whose six-gun battery had become so bogged down that the Marines could no longer pull it. The 51st Pennsylvania had no choice but to pitch in, and soon the exhausted men were pulling inland both the Marine battery and two large rifled guns brought ashore by the Cossack’s captain.

Through near-constant rain and loaded with their own equipment, the soldiers pulled the guns for more than 14 miles through boggy, muddy tracks until they were within range of the Confederate works surrounding New Bern. The unusual anchor-and-cannon corps badge that the future IX Corps would adopt much later was a direct reference to the monumental endeavors of the Coast Division during this period.

Thankfully, the Pennsylvanians were only slightly engaged in the infantry battle that followed and suffered only a handful of wounded. After New Berne fell, the entire Federal force worked to consolidate their gains and improve their living conditions, while making occasional expeditions into the surrounding countryside.

Significant Casualties at South Mills

By April 1, the 51st’s ranks had thinned substantially, the original 981 men who had left Camp Curtin the previous autumn having been reduced to about 350 effectives. Hartranft himself took leave to return to Norristown where two of his children were gravely ill; tragically, they would soon die within a week of each other. During this period, the regiment was in the charge of Lt. Col. Thomas Bell, who was Hartranft’s straight-laced and well-respected second-in-command.

The 51st moved its camp again in early April. Once they were situated, Bell commenced a rigorous program of drill and also tightened the regiment’s discipline. Bell reduced 12 noncommissioned officers to the ranks for improper conduct. This conduct was actually part of a larger problem, namely the uncanny ability of the Pennsylvanians to find supplies of whiskey even in what appeared to be the most destitute areas of the Confederacy.

Bell attempted to teach the regiment to drill by the bugle, but so many of the men were tone deaf that the experiment was a dismal failure. Also instituted was the standing order to bathe every Saturday (when possible)—a tradition that stuck with 51st until it was mustered out.

The regiment again boarded ships in mid-April and sailed northeast to participate in an amphibious landing near Elizabeth City, N.C., as part of an expedition under General Reno. The 51st and Reno’s other regiments were accompanied by Colonel Rush Hawkins’s 4th Brigade.

The combined command moved over dusty roads inland (again pulling along cannon—this time it was two 3-inch rifles) with the mission of making a “demonstration” against Norfolk, Va. The force encountered a Rebel brigade at South Mills in Camden County, N.C., and, after a confused and exhausting fight, Reno abandoned the advance and ordered his brigades back to their ships. The 51st lost 30 men killed and wounded at South Mills—their first significant combat casualties.

Competition in the Camp

Fatigue rendered the march back difficult. Arriving in Currituck Court House, the worn-out Pennsylvanians could not resist the temptation of some illicit fun and proceeded to release all of the prisoners from the town jail, after which they cleaned out the local country store, which was owned by a mouthy secessionist. The used-up troops then marched the final three miles to the landing, brought their wounded aboard the waiting transports, and collapsed after a nearly continuous nightmare-like march of over 40 miles.

Arriving back in New Bern on April 22, 1862, the men were delighted to be met by Colonel Hartranft, who had just returned from Norristown. The Pennsylvanians were given a few days to organize themselves, and it was at this time that they received their first issue of oilcloth blankets, which the men found both novel and useful.

On April 25, a whiskey ration arrived in camp and was put under guard for distribution by the regimental quartermaster. The proximity of the whiskey was too much for the guards to withstand. The detail tapped a keg and sucked the whiskey through a disassembled rifle barrel, which earned each of them a fine hangover and 10 days in a barrel-shirt for their trouble.

In the last week of April, life began to take on a more attractive quality for the hard-used men of Burnside’s command, as excellent rations and other supplies found their way down the coast. The 51st Pennsylvania settled to the more mundane but generally less dangerous business of camp existence. April faded into May, and barring some camp gossip of a rumored attack by the retreating Rebels, little of note occurred. An exception to the tedium came on May 24, when an unpopular order was issued that required all noncommissioned officers to remove their green wool chevrons and trim for replacement with standard-issue blue chevrons.

As June arrived, Hartranft began to recognize that even with frequent moves of camp and steady drill his men were getting itchy, and his company officers began to get creative to fill the men’s time. On June 22, during the regular Sunday-morning inspection, Captain William Bolton decided to offer cash prizes to the three best-groomed enlisted men of his Company A, and competitive spirits ran high. The two best men were so closely matched that the tie had to be broken by Hartranft himself, and only an upside-down coat button on one of the men decided the close contest. From that day forward, the companies of the 51st held competitions with one another for similar honors and, until the regiment mustered out, took great pride in the condition of their weapons and accoutrements.

“Camp Lincoln”

As Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign the north drew to a close after the Seven Days’ battles, orders came for the 51st Pennsylvania to break its tedium and move. On July 1 the regiment was ordered to strike the tents, and next day boarded the schooner Recruit, which made its way down the Neuse River in a rain squall. The vessel collided with another Union ship, causing mass confusion among the tightly packed soldiers. The Pennsylvanians’ anger turned to amusement when they saw that Recruit had rammed their old friend Cossack, and the Pennsylvanians bellowed cheer after cheer when Captain Bennett appeared on the Cossack’s deck.

The fleet was supposed to land its troops in support of McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, which was then at Harrison’s Landing on the York-James Peninsula, but on July 3 word passed through the Pennsylvanians’ ranks that Richmond had fallen. Accordingly, the fleet reversed its course and landed at New Bern on July 4. The next morning the sour truth that the Army of the Potomac had been driven away from Richmond circulated through the division, and once again the men were ordered to strike camp. The regiment reboarded Recruit early on July 6 and headed north for another earnest try to take the Confederate capital, although this attempt would also soon be abandoned. Moving to Fortress Monroe and finally Newport News, the regiment again made landfall on July 10 and established a new quarters that they quickly dubbed “Camp Lincoln.” Although the campsite was adequate, the men were not prepared for the oppressive summer heat and humidity of the Virginia Tidewater region, and life at Camp Lincoln was very uncomfortable. The 51st nevertheless found some amusements, and baseball was a popular pastime among the officers and men alike. Hartranft himself was hailed as one of the best players in the regiment.

During this period, Colonel Edward Ferrero of the 51st New York was given command of the brigade, much to the annoyance of the Pennsylvanians. Ferrero was not particularly popular in the brigade to begin with, and his challenging new schedule of daily drill did not further endear him to the men. In a few weeks’ time he would further insult the 51st Pennsylvania by suspending their whiskey ration as punishment for one of their transgressions. The constant work and summer heat conspired to make the July days pass slowly.

Cat-and-Mouse Toward Washington, D.C.

Recruit sailed up the Potomac River and, on August 4, the regiment landed and moved by rail to Fredericksburg. After a short rest the 51st, along with the rest of the newly organized IX Army Corps, began moving north by hard marches and railroad. The men arrived at Culpeper on August 14. It was apparent that a major campaign was under way.

Moving again on August 15, the suspicion that something big was brewing was confirmed when the regiment watched Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s Confederates making camp on the heights above the 51st’s new position at Raccoon Ford, northwest of Fredericksburg.

Thus began a great game of cat-and-mouse as the blue and gray armies, again on the move after the Seven Days’ battles, began pressing one another for an advantage, and in the intense heat the men grudgingly threw away or stored their excess clothing. In general, the Confederates advanced while the Federals moved northward toward Washington, D.C. During the subsequent days, the 51st Pennsylvania served as the rear guard of the IX Corps’ 2nd Division and lost several men captured by Jackson’s fast-moving vanguard. On August 19 the brigade reached Kelly’s Ford after a 29-mile march and settled down for a rest. While the short break was welcome it was also nerve-wracking due to constant probing of the brigade’s picket line by Confederate cavalry.

Over the next 10 days, the regiment marched hard through the rain and heat with almost no food. On August 29, the Pennsylvanians, in a state of near-exhaustion, reached Manassas Junction, where they joined up with the rest of the Federal army of Virginia under Maj. Gen. John Pope. The Second Battle of Bull Run was already under way in earnest, and the 51st found itself laying in support of Durrell’s Battery D, 1st Pennsylvania Artillery, and standing picket duty.

By nightfall on August 30, the battle was over and Union forces were withdrawing toward Washington. Mercifully for the 51st, it had not been committed to the main part of the fighting, although Ferrero’s brigade was ordered to provide the division’s rear guard during the retreat. This order cost the 51st their knapsacks, which had been unslung, neatly stacked, and subsequently overrun by the enemy. Although pressed hard, the brigade managed to avoid disaster and made its way to Centreville, soaked to the skin by a rainstorm and minus 13 men who had been wounded or captured during the withdrawal. In the short time they lingered at Centreville, the 51st Pennsylvania managed to steal the stored clothing of a German regiment (whose “Cod fer tams” were frequent and loud) to replace some of what they had lost a few days earlier.

Clash at Fox Gap

After again supporting Durrell’s battery during the sharp engagement at Chantilly on September 1, the regiment made its way to Alexandria, Va., where the men enjoyed a short rest and their first hot meal in weeks. Drawing a few items of clothing but still on scant rations, the men moved first to Washington and then to Brookville, Md., on September 9. During the march Ferrero’s brigade was reorganized and was now composed of the 51st Pennsylvania, the 51st New York, and the 21st and 35th Massachusetts.

During the march through Maryland, the brigade enjoyed the attention of loyal citizens and was allowed a short rest at Brookville that featured plentiful rations and time to clean up a bit. The brigade again took to the road on September 11, and on the 14th arrived near Fox’s Gap in South Mountain, where yet another engagement was in progress.

Laying down once more in front of Durrell’s guns, the lads of the 51st watched their artillery wage a rousing duel with Rebel cannon until the late afternoon. As the sun headed toward the nearby peaks, the brigade was ordered up the side of South Mountain to consolidate gains made in the day’s fighting.

Moving into a field bordered by heavy woods, the brigade saw all around them the wreckage of the desperate fight for Fox’s Gap. Earlier in the day the rookie 17th Michigan had pushed the Confederates out of a nearby field and farther up the mountain. What Ferrero, Hartranft, and the 51st did not know was that the 17th Michigan had not stayed there. As Ferrero’s brigade filed into the field to stack arms and boil coffee, the dark tree line to their left exploded with a tremendous flash of musketry. The Confederates had retaken their previous positions after the Michigan troops had moved to another part of the mountain, and the 51st Pennsylvania was caught in a perfect ambush.

Scrambling to form a line and fight back, the brigade lost cohesion and, as the 51st wheeled into line to face their attackers, the green 35th Massachusetts to their rear fired a volley into the surprised Pennsylvanians. The 51st New York hurriedly stepped up and threatened to volley into the confused Massachusetts men if they fired again, and this gave Hartranft’s troops a chance to charge the woods and chase away the Confederate threat.

In the aftermath of the sharp fight, the 51st Pennsylvania shook out a strong picket line and grimly tallied their losses: 6 men killed and 24 wounded. The damage was worse than they knew at the time because General Jesse Reno, who was temporarily commanding the IX Corps, had been one of the first to fall during the initial volley and died shortly thereafter. The news was a sore blow to the already stunned 51st and the corps had just lost an irreplaceable leader. Burnside, who was temporarily responsible for the right wing of the entire Army of the Potomac, gave command of IX Corps to Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox of the Kanawha (4th) Division.

The Battle of Antietam Begins

Pushing forward after a troubled night’s sleep, the regiment looked in wonder at the number of dead draft animals that lined the road. The Confederates were in retreat and IX Corps marched westward in pursuit. Over the next two days the corps captured a number of Confederate stragglers. On the afternoon of September 16, Ferrero’s brigade, with the rest of its division, halted east of Sharpsburg, Md., about a mile from an arched stone bridge across Antietam Creek. The 51st Pennsylvania bedded down and passed a reasonable night’s sleep, disregarding the ever-increasing noise of nearby skirmishers’ rifles, which seemed to erupt from everywhere at once.

Well before daylight, Ferrero’s men were awakened by the sound of heavy artillery fire, followed by the distant rattle of musketry as the sun rose. While making a hasty breakfast, the 51st Pennsylvania was somewhat cheered by the surprise arrival of a bag of mail. Captain Bolton of Company A received a letter from his sister, “and after reading it, [I] destroyed it, and placed the envelope in my pocket, thinking if anything happened to me it might be of use to me.”

With daylight it became obvious that the massed IX Corps was in a less-than-ideal location: Several Union batteries had unlimbered on the high ground between the infantry and Rebel batteries on the opposite side of Antietam Creek, and the two sides were trading iron in the growing daylight. As Confederate overshots began to fall among the four helpless divisions, General Cox ordered them to move west and then south toward some sheltering hills that lay closer to the stream. Cox dispatched Brig. Gen. Isaac Rodman’s division well to the south and Colonel George Crook’s brigade to the north,with orders to move close to the banks of the Antietam and search for fords that were rumored to be in the area. Brigadier General Orlando Wilcox was to keep his division in reserve near the high ground just vacated, thus leaving Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis’s 2nd Division—including the 51st Pennsylvania—in the center, in close proximity to the stone bridge they had glimpsed the night before. Sturgis positioned his 1st Brigade, under Brig. Gen. James Nagle, in a field south of the Rohrbach farmhouse, with Ferrero’s 2nd Brigade slightly east and south of Nagle’s. The 51st moved to the edge of a cornfield and, as reported by one member of the regiment, “came to a halt near a large log barn near Antietam Creek. Here we found a fine spring of water.”

Although no one had yet told them so, it was clear to most of the IX Corps that the stone bridge had to be taken, and it was equally clear that the Confederates did not intend to give it up. During the slow march down the hill around 9 am, the 51st heard a sharp exchange of musketry that turned out to be a probe of the bridge by some skirmishers from the 11th Ohio. About an hour later, the firing suddenly increased again, when the 11th Connecticut of Rodman’s division made a frontal attack on the bridge. Portions of the Nutmeg regiment made it to the creek north of the bridge, and a few men even plunged into the four-foot-deep water to ford the creek, but they suffered heavy losses and retreated in shambles.

Nagle’s Assault on the Bridge

As the 11th Connecticut fell back, Burnside, who had reassumed direct command of the IX Corps and was receiving increased pressure to take the span and attack the Confederate right, ordered Sturgis’s 2nd Division forward. Singling out Nagle’s brigade to make the attempt, Sturgis even offered a general’s star to Lt. Col. Eugene Duryea of the 2nd Maryland if he led a successful assault over the bridge. Duryea agreed and moved the 2nd Maryland from the cornfield down to the Bridge Road on his left, followed closely by the 6th New Hampshire, with the 9th New Hampshire and 48th Pennsylvania in support. Firing a wild volley into the enemy position, the two lead regiments took off down the road in a deadly race toward the bridge, which was nearly 400 yards away.

As soon as they passed the bend in the road near the barn, Nagle’s formations were hit by constant rifle and cannon fire and, though a few men did reach the bridge’s eastern end, they were unable to remain there. Nagle’s two chewed-up regiments retreated up a sloping hill to the east and sought cover. Meanwhile, Nagle’s two supporting regiments tried to move closer but were also repulsed; afterward, the 48th Pennsylvania moved across the plowed field to their right to rejoin their battered comrades, while the 9th New Hampshire huddled along a fence near the creek.

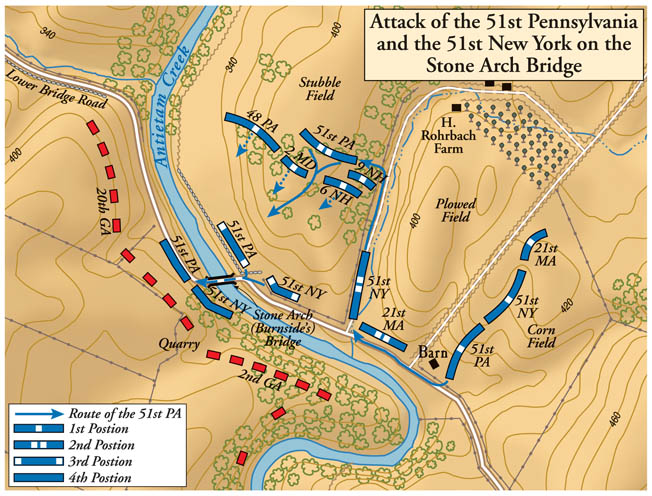

After Nagle’s brigade marched from the cornfield, Ferrero’s regiments filed into Nagle’s former positions. The 51st Pennsylvania stacked their blanket rolls and knapsacks and placed their left company closest to the Bridge Road near the barn, which by now was serving as a field hospital. The 51st New York formed on the Pennsylvanians’ right, and the 21st and 35th Massachusetts took up supporting positions slightly to the north and east.

As the sounds of Nagle’s attack diminished into an artillery exchange, Ferrero’s men were finally able to get a glimpse of what was happening. Bolton wrote in his diary, “The road leading to the bridge is strewn with … dead and wounded. It is a sickening sight.” For nearly an hour, Hartranft’s men had been watching other soldiers disappear into the tall corn, then heard the hellish noises of battle. Now the grisly epilogue to those assaults became evident when groups of mutilated men came stumbling back through the cornrows, headed to the rear. The sight nearly unnerved the inexperienced troops of the 35th Massachusetts, and none of Ferrero’s men had any illusions about what was happening at the bridge.

Once again the volume of fire rose, as Nagle’s partially reformed brigade again tried to take the bridge, this time charging from the hill where they had gone to ground. Almost before it had started, the attack ended in disaster, and the beaten Marylanders and New Hampshire men fell back again. It was just before 11 am, and Nagle’s brigade was used up. After Nagle’s failed assaults, Ferrero’s brigade was next.

“Will You Give Us Our Whiskey, If We Take It?”

Burnside was nearly beside himself by this time and, in a final desperate bid, sent a message through Sturgis for Ferrero to “take the two 51sts out of the 2nd brigade” and let them try. Sturgis reported: “[I] directed them to charge with the bayonet. They started on their mission of death full of enthusiasm.”

Ferrero, knowing his brigade was already worn out from the hard campaigning of the previous days, was hoping instead to ford the stream at a less dangerous point. After a series of short but heated exchanges between Ferrero’s aide, Lieutenant John Hudson, and Sturgis, Ferrero bitterly obeyed. Bolton recorded, “Finally at 11 o’clock a.m. the dreaded order came from Burnside to Ferrero to take the 51st PA and the 51st NY holding the 21st Mass. in reserve, and take the bridge at all hazzards [sic].”

For his part, Ferrero was eager to regain some of his regimental commanders’ respect, because he had made an embarrassing, errant order earlier that morning that led to an argument with Hartranft.

Ferrero rode up hard to his brigade and, ordering them to their feet, shouted:“It is General Burnside’s special request that the two 51sts take that bridge. Will you do it?” The cynical silence that followed was broken when Corporal Lewis Patterson shouted from the Pennsylvania ranks, “Will you give us our whiskey, if we take it?” Eyes alit at the opportunity, Ferrero wheeled around and exclaimed, “Yes, by God, you shall all have as much as you want, if you take the bridge!” In a quick hedge that was not lost on the soldiers, he continued: “I don’t mean the whole brigade, but you two regiments shall have just as much as you want, if it is in the commissary or I have to send to New York to get it, and pay for it out of my own private purse, that is if I live to see you through it! Will you take it!?” The deal was struck when a resounding “YES!” filled the air. Afterward, Patterson’s bold suggestion was looked on with some wonder because he was an abstainer.

The View From the Hill at Rohrbach Farm

After some consultation, the brigade began marching by the left flank toward the Bridge Road with the 51st Pennsylvania in the lead. Along the way, Hartranft encountered Duryea of the 2nd Maryland, who warned him “not to go up the road”—good advice, but difficult to heed. With the 51st New York following, the Pennsylvanians moved along the road and past the barn just as Nagle’s brigade had done earlier.

As they reached the fork in the road south of the bridge, the men were astonished when Hartranft suddenly led them to the right—away from the bridge—up the fenced lane that led to the Rohrbach farm, which was near the hilltop that overlooked the bridge. The 51st Pennsylvania had turned their backs to the Rebels dug in across the creek. Nevertheless, according to Bolton, “from that moment the regiment received volley after volley of grape, musketry, shot and shell, filling our faces and eyes with sand and dirt, all this time reserving our fire.”

On gaining the crest of the hill, the 51st Pennsylvania turned left and jumped over the fence that lined Rohrbach’s lane, entering the same depression in the field on the north side of the road where the remains of Nagle’s Brigade had gone to ground. Following the Pennsylvanians, the 51st New York also filed right off the Bridge Road into Rohrbach’s farm lane, but stopped at the base of the hill, perpendicular to the creek and facing upstream. The 21st Massachusetts formed a short, oblique line on the New Yorkers’ left flank, parallel to the Bridge Road.

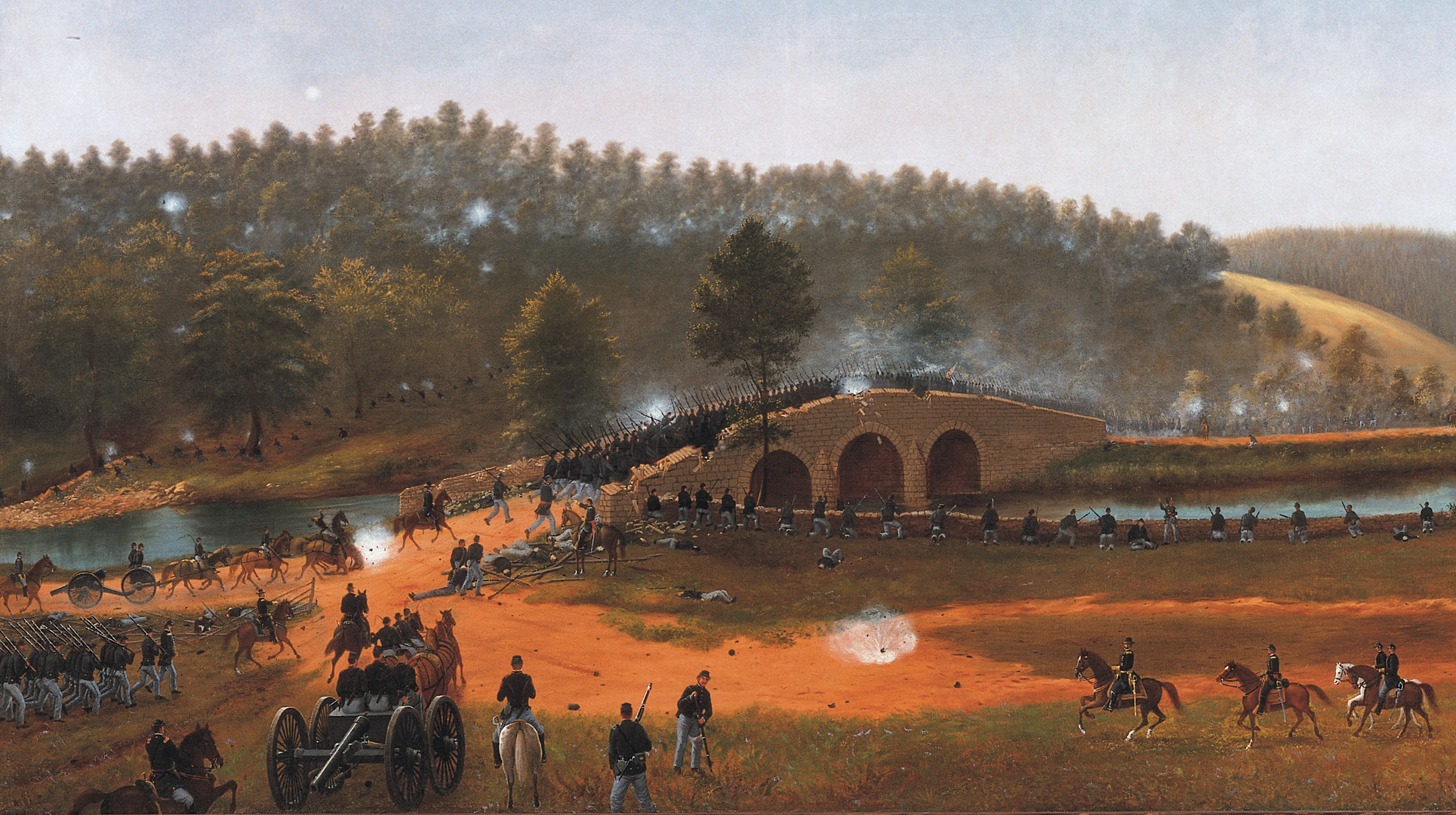

From their new positions, the twin 51sts could finally see what they were up against. The bridge crossed the creek from the open ground on the eastern bank, but terminated at a small lane on the far side. Overlooking the bridge and lane was a steep and wooded bluff that rolled higher and higher to a hill nearly half a mile to the west. The wooded slope near the bridge seemed alive with well-dug-in Confederate soldiers, and the distant hill was crowned with enemy guns that had been refining their aim on the bridge all morning as they pounded the Federal batteries and infantry with everything they had including, according to one account, chunks of railroad track.

The Confederate Defenders Brace For an Assault

Across the creek the Southern defenders saw the new Union troops massing and, for the fifth time in three hours, began throwing metal as fast as they could. Situated in trees and rifle pits on the west bank of the creek were two Georgia regiments: the 2nd (south of the bridge) and the 20th (to the north). These two small regiments had covered the span with a paper-thin line all morning, often with eight feet or more separating each man from the next. Worse, the persistent Union artillery and musketry had thinned the gray line even further, and the remaining men were getting tired.

The supporting Confederate guns on the hill behind the Georgians were worn out and bloodied too, but both little groups believed they had one more good fight left in them. Colonel Henry Benning, in local command of the dwindling Confederate force, thought so too. Part of Benning’s confidence stemmed from the excellent ground his troops occupied. The controversial politician-general Robert Toombs, in overall command of the Confederate forces near the creek, described the position in his official report: “From the nature of the ground on the other side, the enemy were compelled to approach mainly by the road which led up the river for nearly three hundred paces parallel with my line of battle and distant from fifty to a hundred and fifty feet, thus exposing his flank to a destructive fire the most of that distance.”

The scores of dead and wounded Federals littering the far bank confirmed Toombs’s words. Unfortunately for the Southerners, confidence alone could not ease Toombs and Benning’s growing problems. The bridgehead’s two defending regiments had less than 400 men, and their ammunition was nearly exhausted. Several hundred yards downstream, a Union regiment—the 28th Ohio of Rodman’s division—was forcing its way across the creek. Further, the Federals had brought up more artillery that was, by now, pounding the wooded slope with round after round of canister. Toombs sent word to the Georgians that, should the blue troops manage to get across the bridge, they should retire to the patchwork Confederate line that was being formed in the direction of Sharpsburg. It was a little after 12 noon, and it was clear that the Yankees were going to try again.

The Twin 51sts Advance

Immediately after the 51st Pennsylvania had jumped the fence along Rohrbach’s farm lane near the summit of the little hill, they were ordered to form by company into line just behind the prone ranks of Nagle’s 2nd Maryland and 6th New Hampshire, whose men were still taking potshots at the Rebels from the crest of the knoll. As soon as the regiment sorted itself out, Hartranft ordered the 51st to fix bayonets, and reformed them “in close column of division just behind the crest. When the formation was complete I ordered the movement upon the bridge.”

The energetic Lieutenant Hudson was with Colonel Ferrero at the base of the hill near the barn when he heard a strained cheer come from the knoll and, looking up, “saw the 51st Pennsylvania rush (not very fast—tired soldiers don’t go very fast)” directly toward the bridge.

As the Pennsylvanians’ column of divisions (two companies abreast) moved through the New Englanders to their front, the world seemed to explode. The remains of Nagle’s brigade lining the knoll began firing with a will at the Confederate positions, and elements of Nagle’s 48th Pennsylvania and 9th New Hampshire began scrambling forward on the flanks of the 51st to offer what support they could. Meanwhile, the 21st Massachusetts, back along the creek bank at the intersection of the Bridge Road and Rohrbach’s lane, increased their fire, as did the 51st New York, and all the while the Federal guns on the hills behind them redoubled their efforts, throwing enormous quantities of shot over the creek.

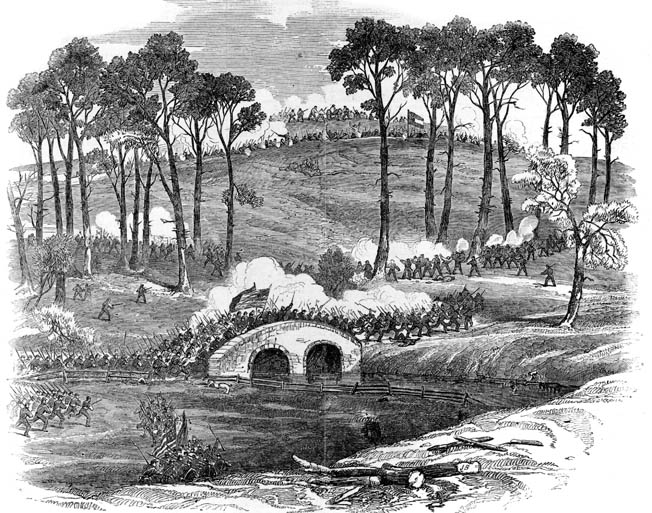

Despite all this, the Georgians were ready and, as the 51st Pennsylvania stumbled and ran down the slope, hundreds of muskets turned a murderous fire on them. Men began falling from the careening column at what seemed like every step, and the Pennsylvanians broke into a run in a bid to get to the small stone wall that ran along the creek bank north of the bridge. The 51st New York, taking a cue from their twin regiment, jumped over the fence along Rohrbach’s lane to their front and raced toward the bridge with equal determination. They finally stopped in a line behind another rail fence directly south of the crossing.

Returning Fire on the Georgians

Avoiding the bodies that remained on the slope from the previous assaults, Hartranft’s men finally tumbled into line behind the little wall and took a moment to catch their breath. As he ran toward the cover of the bridge abutment, Hartranft realized to his frustration that a stout rail fence, which was linked into the abutment itself, blocked the 51st’s route onto the bridge—the regiment was trapped. He quickly ordered a handful of enlisted men to tear down the fence and, under tremendous fire from the Southerners, they managed to remove a few panels. Pennsylvanians tumbled through the new opening and threw themselves down on the road behind the stonework parapets— the eastern entrance of the bridge was theirs.

Simultaneously, a squad of New Yorkers made their way to the east end of the bridge as well, and both 51sts began to return the Rebels’ fire with a vengeance, discharging round after round into the just-visible Confederates. It was the Georgians who began to suffer now, but they nevertheless maintained a steady fire into the paralyzed Union regiments while their own artillery continued to bark from the hill behind them. Hartranft was directing fire and shouting orders with a steadily failing voice when Hudson made a sudden appearance near the northern abutment, bearing Ferrero’s impatient demand to move the 51st over the bridge immediately. Hartranft was a bit shocked—the Rebel fire was certainly slackening, but the eager Federal artillery was sending a wall of fire just over the top of the bridge, threatening to decimate anyone who tried to cross.

Realizing he had little choice but to obey, Hartranft took Hudson in tow and scurried to the southern side of the bridge to find Colonel Robert Potter of the 51st New York. Ordering Potter to follow the Pennsylvanians across, Hartranft ran back to his men and passed the word: It was time.

“I Can’t Halloo Any Longer!”

In a moment of electric excitement, Captain William Allebaugh of Company C found First Sgt. William Thomas nearby. Accompanied by the three color bearers and one other member of the color guard, Allebaugh and Thomas made a dash for the bridge. Rounding the corner and pushing a few feet onto the bridge itself, they planted the colors on the road and called back to the startled 51st Pennsylvania. Hartranft, waving his hat toward the colors, rasped out, “Come on, boys, for I can’t halloo any longer!” and was gratified to see his veterans suddenly stand up, rush through the gap in the fence, and pour onto the bridge, stopping only to fire or to avoid the men who fell in front of them.

Allebaugh’s Company C seems to have been the first onto the bridge, followed by Captain William Blair’s Company G. However, the order that the companies reached the bridge really did not matter because almost immediately all was chaos, and any order or formation melted away as hundreds of men in blue tried to push through the bottleneck. Just as he was about to lead his Company A onto the eastern approach, the observant Bolton suffered a vicious hit, a Southern bullet smashing out all the teeth from his right jaw and exiting just below his left ear. Bolton stumbled to the rear and fell senseless, eventually waking up in the barn-turned-hospital from which he’d started an hour before. To add to the congestion and chaos, Colonel Potter was standing on the southern parapet, screaming like a madman and urging the men of his 51st New York to move across as well. Allebaugh’s little group turned, raced across the span and, as the colors went forward, so did the 51st Pennsylvania. They were over!

General Sturgis reported, “The Stars and Stripes were planted on the opposite bank at 1 o’clock p.m., amid the most enthusiastic cheering from every part of the field from where they could be seen.” At the opposite end of the bridge the quick-moving regiment turned to the right and ran north along the Bridge Road. The leading elements began to find cover and fired at the occasional target. To their surprise, the Pennsylvanians took several Confederate prisoners. Hartranft managed a peek at his watch and was amazed to discover the attack had lasted only 13 minutes; it had seemed much longer.

Stampede Across the Bridge

The Georgians had finally had enough. Nearly every one of them was now out of ammunition, and most began to fall back over the bluff as ordered; however, there were scattered groups that could not or would not leave, while others were simply too tired to run and surrendered. When they finally reformed, there were fewer than 250 men remaining of Toombs’s and Benning’s original 400, but even so it was a remarkably low price to pay in trade for what they had done: The little group had nearly defeated an entire Federal division and had stymied a whole corps for several critical hours.

The Pennsylvanians moved north along the Bridge Road far enough to make room for the 51st New York to file in on their left and, except for the occasional artillery round, Confederate resistance at the bridge had completely crumbled. The numbed men of the 51st Pennsylvania were nearly out of ammunition a testimony to the intense firefight at the stone wall, so, being veteran soldiers, they did the only thing that made sense to them: They stacked arms by the stream and began boiling coffee.

Like his men, Hartranft began to recover his bearings and, as he surveyed his situation, he noticed something peculiar—the two 51sts were by themselves on the western side of the creek. The Federal commanders had concentrated so hard all morning on taking the bridge that they had neglected to design a follow-up plan. Simultaneously, Ferrero, still on the eastern bank, unhappily watched as the 51sts stopped their advance and called for his Massachusetts regiments to immediately cross the bridge. As quickly as the order was delivered, the 21st and 35th Massachusetts moved toward the bridge, but the bruised regiments of Nagle’s brigade suddenly wanted the honor of crossing the span next, and a stampede ensued. Men from every command in Sturgis’s division made for the bridge.

The nearly solid blue-clad mass pushed for the far side and, in so doing, grabbed the attention of the still-feisty Confederate artillerymen on the far hill. As flying shells began to make the crossing a very hazardous place once again, Ferrero’s Massachusetts men made it to the far side and filed right, then up the bluff, pushing the Pennsylvanians farther north.

Lieutenant Colonel Bell of the 51st Pennsylvania, who had gone looking for reinforcements a few minutes earlier, was returning from the bridge after his redundant errand, and became one of the regiment’s final casualties that day when a Southern canister ball grazed his skull. Rolling down the creek bank into the regiment’s stacked muskets, Bell seemed only stunned at first, but he died a few hours later. This was a hard blow to the 51st, and a harder blow to Hartranft, who would mourn his dear friend for a very long time.

The 51st Gets Relieved

Over the next two hours Ferrero’s brigade, which had moved north and west along the top of the bluff, waited in disbelief for other Union regiments to cross over and take up the fight. While they waited, the systematic Confederate artillery fire caused the Pennsylvanians to lose another handful of men wounded, and the regiment’s beautiful, blue flag was torn to pieces when a shell passed through it.

Well over an hour after they had fired their last round, the 51st was finally relieved by the 45th Pennsylvania. The 51st had totally exhausted its ammunition and, after holding a forward position with nothing more than their bayonets, Hartranft ordered the regiment back to the Bridge Road in twos and threes.

As they struggled to reorganize themselves back at the creek, the Pennsylvanians began to reconcile the huge gaps that had rent their ranks during that maddening day. Of approximately 335 men who had marched away from the barn that morning, more than one in three were confirmed casualties: 29 were dead or dying, five of the wounded would die from their wounds before the year was out, and 91 wounded men were in the care of the surgeons. The 51st New York had been hurt too, losing 87 men during the charge. The twin regiments’ casualties accounted for almost half of the Federal losses in front of the stone bridge that day.

Whiskey For the 51st

Ferrero’s brigade played a further role in the late-afternoon fighting near Sharpsburg, the unlucky 35th Massachusetts alone losing over 200 men while waiting for reinforcements that never came. As the sun set that evening, the men of the two 51sts, like future historians, would wonder what went wrong after their sacrifice at the bridge that noon. Inexplicably, it had taken nearly three hours for the generals to launch the long-awaited attack on the Rebel right and, when Burnside’s attack finally came, it was too late. The Confederate army would escape the next day.

The tough boys of the 51st Pennsylvania continued their fight for three more years, and finally mustered out as a veteran volunteer regiment on July 27, 1865. Before that day, however, the Pennsylvanians would fight more hard battles in places like Fredericksburg, Vicksburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, and many others, always with their three flags flying proudly. But they would be remembered best for their wild and deadly charge on “Burnside’s Bridge” that bloody September afternoon in the central Maryland countryside.

In early 1864 Hartranft was given a brigadier’s star and turned over command of the 51st to the newly promoted Colonel William Bolton, who had recovered from his terrible Antietam wound.

On September 19, 1862, in the same ceremony that saw Ambrose Burnside promoted to major general, Colonel Edward Ferrero was promoted to brigadier general as a reward for his brigade’s actions at Antietam. Not coincidentally, the next day the 51st Pennsylvania Volunteers finally got their whiskey.

Thank you for this explicit detail of the fighting at the

Antietam/Sharpsburg Bridge, AKA Burnside’s Bridge.

The real life stories were great to read.

Thank you for work in researching the 51st PA. I’ve read some of it before (e.g., in Bolton’s journal) but you added many new details. I’m interested in the regiment because my great-great-grandfather, Theodore Gilbert, served in it. He started out a sergeant gotten broken to the ranks because of his comments to his superiors during the Roanoke landing & shortly after won 3rd place in the 1st regimental best kept kit contest. He ended up getting his leg shattered during the battle of the Wilderness. He had to muster out after the hospital but joined the another PA regiment & guarded trains during the rest of the war and mustered out as a 2nd Lt.