By Joe Kirby

When Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, the hard-driving commander of the Twentieth U.S. Air Force based in Guam, decided to change tactics in early 1945 to boost the effectiveness of the B-29 Superfortress, it was the Bell Aircraft plant in Marietta, Georgia, that ultimately provided him with the stripped-down bombers that played such a key role in ending the war in the Pacific.

The Bell plant, usually referred to both then and now as The Bell Bomber Plant, had already churned out 357 “regular” model B-29s since the first one, assembled mostly by hand, rolled out of the plant’s doors in November 1943.

Between January and September 1945, that plant produced all 311 of the B-29B models that shouldered much of the load after LeMay decided to switch from high-altitude bombing to low-altitude firebomb attacks. He also decided the planes could fly faster and have less trouble achieving takeoff speed if they weighed less.

Japanese fighter strength was in decline and their attacks tended to come from the rear, so LeMay’s solution was to remove all defensive armament except for those in the tail. That saved the weight not just of the guns, ammo, and turrets, but also of their fire-control system (a then cutting-edge analog computer that corrected for distance, speed, temperature, gravity, barrel-wear, etc.). LeMay also decided that leaving the planes unpainted would save each one several thousand pounds of unneeded weight.

Ground had been broken for the Marietta plant in March 1942 just three months after Bell Aircraft head Larry Bell chose the city as the site for a factory in which to assemble the mammoth new bombers under contract from Boeing.

Why Marietta? It was just a small town near Atlanta in the middle of the Cotton Belt with a prewar population of only 8,000—very few of whom had college degrees or experience in an industrial setting. It was best known, if known at all, for being in the shadow of Kennesaw Mountain of Civil War fame. Some in Washington initially resisted the idea of training farmers to assemble what was to be, up to that point, the biggest and most technologically advanced plane ever built.

But there were advantages to the Marietta site as well. It was only 15 miles from the large, untapped pool of labor in Atlanta, which lacked any other munitions plants. Those workers could commute via the Marietta-Atlanta trolley while components for the B-29 (such as the plane’s 18-cylinder Curtiss-Wright R-3350 engines assembled elsewhere by Pratt and Whitney) could be delivered to the plant via the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway (today’s CSX), whose tracks skirted the western edge of the chosen site.

In addition, the plant could make use of a runway that was already in the very early stages of development by the city and county governments as part of a deal with Eastern Airlines’ President Eddie Rickenbacker of World War I fame to handle the overflow from Candler Field in Atlanta (today’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport).

Marietta leaders had traveled to Washington, D.C., in the autumn of 1940 hoping to land federal funding for their airport and wound up hitting the jackpot, thanks in part to President Franklin Roosevelt’s crash rearmament program—and also to a fortuitous coincidence.

In 1940 Congress was still under the sway of antiwar isolationists and was reluctant to fully fund FDR’s plans, so he persuaded that body to pay for the construction of more than 450 civilian airports around the country. If war came, they could be converted to military airbases. And, as luck would have it, the Army officer in charge of developing those civilian bases was a native of Marietta.

The Marietta delegation was walking the halls of the Civil Aeronautics Administration when the city’s mayor unexpectedly saw on an office door the name of his Marietta boyhood friend, Major Lucius D. Clay (West Point, 1918) of the Army Corps of Engineers. The mayor barged into the office—and soon learned that Clay was the de facto head of FDR’s airport construction program, despite his comparatively minor rank.

Clay, the son of late U.S. Senator Alexander Stephens Clay of Marietta, had served as chief engineer under MacArthur (and his chief of staff Dwight D. Eisenhower) in the Philippines until 1937. Not long after Pearl Harbor Clay was promoted to director of material procurement for the Army. (After the war he would serve as the four-star military governor of the U.S. sector of Occupied West Germany and commanded the Berlin Airlift before retiring in 1949.)

But in 1940, Clay’s title was secretary to the approval board for airport construction and assistant to the administrator of the CAA. He told the Marietta leaders standing in his office that he wanted to see his hometown do well and that, if they could procure the land for an airport, he would ensure they got federal funding for it.

Clay proved as good as his word, first getting the city the funding needed for the runway (which initially was christened “Rickenbacker Field” and today is the centerpiece of Dobbins Air Reserve Base), and then a year later helping persuade Larry Bell that Marietta and its new runway would be an excellent location for the B-29 plant he had just been tasked with building.

The government paid to build the plant but left it up to Bell to decide where it should go.

“The [Army] Air Force had to have a new plant—and a big plant,” Clay told his biographer, Jean Edward Smith. “And they came to me to ask for a list of possible places where there was both a labor supply available and an existing airport. And I happened to remember Marietta, so I gave it to them as one of the names. It had tremendous labor potential—both from Atlanta and from the surrounding mountain area.”

Robert Lovett, who, in 1941, was assistant secretary of war for air, later told Smith that the reason the Bell plant went to Marietta was, “It was an area with a large population of first-class Anglo-Saxon farmers with not much to do in the way of farming. They were men with a mediocre amount of education, but a good farm boy from that area could take any kind of machine apart and put it back together again. He had to in order to live on his farm. So you had a good basic labor force. And when they opened the doors, the plant was flooded with them.

Lovett also noted that Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Walter George was from Georgia, and the congressman who was approaching seniority on the House Military Affairs Committee, Carl Vinson, also was from Georgia.

The government spent $72 million to construct the plant—nearly as much ($83 million) as it spent on another major construction that got started in 1942: the Pentagon. The Bell plant was the largest industrial facility ever built south of the Mason-Dixon Line, a distinction it reportedly still holds.

After breaking ground on March 30, 1942, the 3.2-million-square-foot plant was completed just 54 weeks later, even though there were severe war-related shortages of construction materials, such as the 32,000 tons of steel used for the main assembly building. That building was a half mile long and approximately a quarter mile wide (a size comparable to 63 football fields) and boasted enough space for a pair of parallel final assembly lines.

The facility’s construction was an enormous investment in money and materials, especially when one realizes the prototype for the new bomber, the XB-29, did not make its maiden flight until September 21, 1942—nearly six months after the Marietta groundbreaking.

No attempt was ever made to camouflage the Bell plant, presumably because by the time it was coming on line in late summer 1943 the tide of the war had turned sufficiently that enemy air attacks were no longer a concern.

The plant had another notable distinction for that era—a feature usually limited to government buildings and large theaters in the prewar era. But, with the Allies struggling against the Axis in the first two years of the war, there were real fears that German bombs might at some point be raining down on the East Coast, so the plant was designed to meet blackout specifications so as not to emit any light at night, which in turn tended to rule out including windows. Yet a windowless building would be unbearably hot during a Georgia summer.

In addition, since the B-29 would be of all-metal construction, the plant would need to have a constant temperature to prevent metal aircraft components from expanding and contracting.

More than 100 contractors and their crews labored 24/7 to build the plant. They worked so quickly, in fact, that many concrete walls and support footings for the plant’s basement and subbasement were complete before those basement areas had been completely excavated. Once those walls and footings were complete, the builders realized the doors to the basement were too narrow for them to get their mechanical excavators back in to finish the job. Yet there was far too much dirt still to be moved for a simple pick-and-shovel operation. The solution? Mule-drawn equipment was hired from nearby farmers.

Workers had started assembling components of the first B-29 even before construction of the main building was complete. Harold Mintz, a foreman in the plant at the time, recalled in a 2000 interview that assembly work was taking place even in areas where the roof was not yet complete.

“While we were starting off, the end of the shift didn’t mean anything,” he said. “If we had something going there we just stayed. [At night] I could look up and see the stars and everything with no roof.… It rained in [on us].”

Bell brought a cadre of experienced workers to Marietta from its plant in Buffalo, New York (where the company built the P-39 Airacobra and P-63 Kingcobra), but the bulk of the workforce hailed from the greater Atlanta area.

Thousands of others, drawn by the prospect of steady work at 60 cents an hour, flocked from the Southeast to Marietta (literally doubling its population in the process) to work at the plant. And even though special training schools were set up to teach the rudiments of riveting while the plant was being constructed, it was still slow going.

“The Marietta plant is probably the best illustration available of the difficulties we have had in production,” wrote Brig. Gen. Bennett Meyers, assistant chief of air staff of the Army Air Forces, who was acting at the time as a trouble-shooter for General Henry “Hap” Arnold on the B-29 program. “Believe it or not, people who were employed to make aluminum planes had to be shown what a sheet of aluminum looked like.”

Stinson Adams, Jr., of Marietta, who worked as an inspector in the plant, recalled that car mechanics had skills that could be put to good use. “If they were mechanically inclined and knew how to tighten a nut and were willing to work, we could make an aircraft mechanic out of them,” he said.

Richard Croop, part of the cadre of Buffalo Bell workers who came South in 1942, recalled, “A lot of people didn’t know what a drill or drill motor or rivet gun was. They’d never seen rivet guns.”

Yet the Southerners were willing to learn—and few of them were strangers to hard work.

Most of the plant’s workers had not finished high school, and many of them had gone no farther than eighth grade. Most had never seen a time clock or a time card, and more than a few workers were illiterate and “signed” their card each week with an “X.”

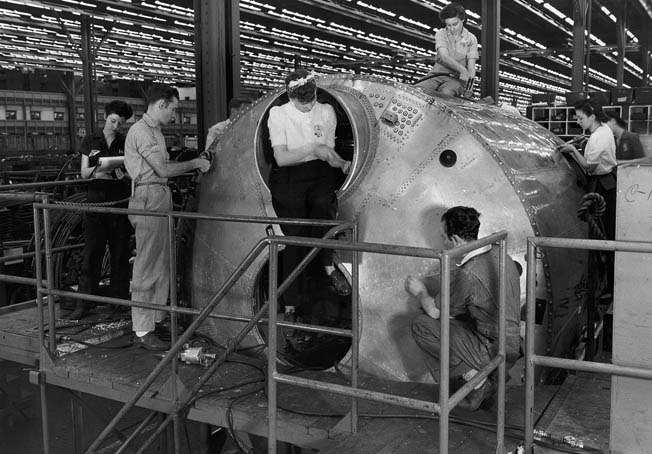

By 1944, the plant employed 28,000 people. Some 37 percent of the Bell plant’s workforce was female, but contrary to the popular myth that has grown up around World War II defense plants, the majority were not “Rosie the Riveters.” Rather, women staffed a wide array of positions.

In addition to the typical secretarial/cafeteria jobs, they also worked as engineers, tool designers, draftswomen, estimators, production illustrators, bicycle couriers, chauffeurs, inspectors, nurses, radio tower dispatchers, and gun-toting security guards. They also served as riveters (handling rivet guns that weighed as much as 15 pounds), die makers, sheet-metal fabricators, toolmakers, welders, and crane operators.

The Bell plant also opened new employment horizons for local black workers; it had more than 2,000 African Americans on its payroll in January 1945, although it unfortunately also seemed to have a quota system in place. No more than 800 blacks at one time were ever working in skilled-labor positions, according to research by Kennesaw State University History Professor Emeritus Dr. Tom Scott. And, while Bell was a Northern-owned company, it adhered to the South’s “Jim Crow” laws at the plant, with separate restrooms and water fountains for blacks and whites.

Interestingly, the plant also employed a number of midgets and dwarfs, who could easily squeeze into tight spaces, such as the planes’ nose cones, where normal-sized adults could not. And they could work standing up in such places and not become as fatigued as a full-sized person, who would have to kneel or crouch. There also were blind workers whose job it was to sort by hand the stray rivets swept up off the floor.

All told, the plant employed 1,750 disabled workers—no doubt at least in part a reflection on the plant’s manager, James Carmichael, who had been left severely disabled by a motor vehicle accident as a teen.

With so many young men in uniform, the plant employed many older workers who under normal circumstances would never have been employed in a heavy industrial setting; the oldest of them was 81-year-old riveter Helen Dortch Longstreet, widow of late Confederate General James Longstreet (she married him in 1897 when he was 74).

One of the plant’s most remarked on features by visitors of the day were the rows of thousands of fluorescent lights overhead from one end of the plant to the other. The plant had a crew that did nothing but change bulbs, starting at one end of the plant in the morning and working toward the other end; then reversing direction to swap out the bulbs that had burned out since its first pass earlier in the day.

Vintage photos of the sprawling factory give a good representation of what it looked like at full production but can’t begin to convey what the plant sounded like: a cacophony of thousands of rivet guns, steel presses, drills, welding torches, and other machinery. Few, if any, workers wore ear protection.

Like many munitions plants, the Bell factory was visited by numerous celebrities promoting bond sales and the war effort. They included movie stars Bob Hope, Al Jolson (in one of his final public appearances), Mary Pickford, and Jane Withers, as well as General Dwight Eisenhower’s wife Mamie and golf legend Bobby Jones. The plant also was visited in June 1945 by two of the “flag-raisers” from the just concluded battle of Iwo Jima in a war bond sales drive.

Still another visitor in the summer of 1945 was Lieutenant Mildred Dalton, one of 77 Army nurses christened “the angels of Bataan and Corregidor.” They had been liberated that February from hellish captivity at Santo Tomas in Manila by General Douglas MacArthur’s men. After a month or so of recuperation, she was sent on a war bond tour that brought her to Marietta.

The first 16 of the more than 600 Superfortresses built at the plant were assembled mostly by hand, and the very first of them rolled out the door in early November 1943; three more followed by year’s end. Production slowly ramped up to a plane a day by the summer of 1944, then to two a day by May 1945. After test-firing the engines on the tarmac, the planes then were towed to another hangar in which their armaments, radios, and radar were installed.

It was a point of local pride that not a single Marietta-built bomber ever crashed on its ensuing test flight.

Those Superfortresses and the men who flew them were crucial cogs in LeMay’s firebombing offensive against the Japanese homeland in the spring and summer of 1945. And though neither the Enola Gay nor Bock’s Car were built by Bell, they were similar in most respects to those that were.

Within weeks of the war’s end, the Pentagon canceled its contract with Bell, and the plant almost immediately began laying off its workers. They were all gone by January 1946 and the mammoth plant was used as a storage facility for aircraft manufacturing equipment shipped there from other plants. From a high of 28,000 workers during the war, the plant employed just 79 people in the late 1940s while operated by the Tumpane Corporation.

That changed in 1950 after the Korean War broke out. Most of the country’s B-29 fleet had been mothballed at Pyote Air Force Base in the Texas desert. The Pentagon chose Lockheed to reopen the old Bell plant (officially known as Air Force Plant No. 6) with two purposes in mind: to recondition and upgrade 120 B-29s brought from Pyote, and to start assembling what ultimately were 394 copies of the country’s first mass-production jet-powered bomber (under contract from Boeing): the B-47 Stratojet.

Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin) continues to operate the old Bell plant, which through the years produced 131 C-5 Galaxy cargojets, 285 C-141 StarLifter cargojets, 202 JetStar VIP Transport planes, and all 195 copies of the F-22 Raptor fighter jet.

The plant’s flight line now is building part of the fuselage for the F-35 Lightning II fighter and updated versions of the revolutionary C-130 Hercules cargo plane (now designated the C-130J). Nearly 2,500 copies of the “Herk” have rolled out the plant’s doors since 1955 (including 24 in 2015)—enough to make it the longest-continuously manufactured military aircraft in history.

And, fittingly, a sizable number of the people assembling those C-130s are the sons and daughters—and grandsons and granddaughters—of the workers who labored in the plant in 1943-1945 building Bell’s B-29s.

The writer made a comment about no windows in the plant in Georgia making B-29’s and said it would be too hot in the summer time for the metal. But it was never explained how they solved the problem of keeping the heat down in the summer time.

Gary