By Glen Barnett

Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals, or M*A*S*H units, were popularized by Richard Hooker’s novel series, the 1970 film starring Donald Southerland and of course the long-running television show starring Alan Alda. But the idea for a portable surgical or field hospital came decades before the Korean War. The idea came from General Percy J. Carrol, chief surgeon of the U.S. Army. He envisioned a hospital unit housed in tents whose personnel could strike camp and carry all of the unit’s equipment and supplies to a new site and set up again, saving valuable time for treating patients close to the battlefield. His idea was first put into practice in June 1942.

Australia Receives the First pre-MASH Units

Two such hospitals were equipped and sent to Australia with American troops. More would follow. Each hospital consisted of four officers, three of whom were surgeons, and 25 enlisted men, including medical, surgical, laboratory, administrative, and mess personnel. While awaiting orders to move out from Australia they practiced packing up and moving, refining the procedures to be used in the jungles of New Guinea.

The station hospital at Port Moresby was a busy place. “Four days after we were given this real estate, which was covered by high kunai grass, we had 500 patients,” remembered Lt. Col. C.T. Wilkinson, one of the doctors who served there. “They had to bring in water from miles away and there were Japanese air raids every night. Doctors did the carpentry for the operating room and the nurses painted the interior.”

In October the portable medical units moved to Port Moresby with the 32nd Division. They were subsequently located with the active units until the victory at Buna in January.

Surgery Within Earshot of Combat

There were no nurses at the forward portable hospitals at Buna. Here surgery took place within earshot of the firing. Sometimes enemy patrols were found at night inside the hospital area. On more than one occasion enemy planes used the red crosses on the hospital tents as targets for treetop-level strafing runs.

The first attempts to provide medical care at the front were dashed when the 22nd Portable Hospital was shipped in on boats that were sunk by the Japanese on November 16. All of the supplies and equipment and some of the personnel were lost.

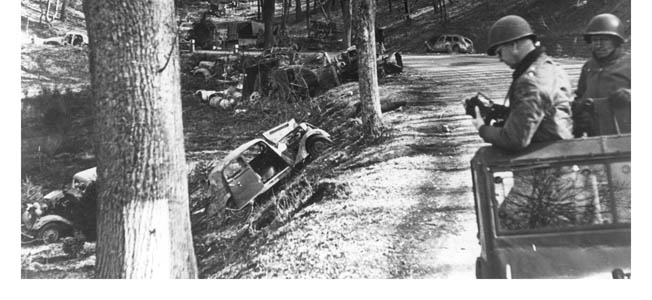

Conditions were appalling for the next month. There were shortages of everything. Swarms of malarial mosquitoes blackened the skin of patients. Bold swamp rats did not care if they chewed on the living or the dead. Fever was treated by placing a shivering man in a stream until his temperature came down. Maggots infected wounds. Records were lost, and evacuation by litter or on the hood of a jeep was torturous.

Infections As Well As Battle Wounds

Fully 70 percent of the battle wounds at Buna were in the limbs. The Japanese .25-caliber bullet tended to wobble in flight and strike slightly off-center. This resulted in a large exit wound, causing more damage than a bullet with a perfect trajectory.

All types of battle and personal injuries were treated in the portable hospitals. Plaster of Paris casts were routinely applied to immobilize fractures. Sodium pentathol was the most common anesthetic used at the front due to the flammable nature of ether.

Infectious jungle-borne disease was perhaps more prevalent than battle wounds at the portable hospitals. At Buna, the doctors as well as the patients were infected with malaria, dysentery, jungle rot, and other maladies. Two hundred men at Buna died of typhus alone. Almost every man on both sides contracted malaria. Other diseases claimed their share of victims as well.

The Battle of Buna was an overwhelming experience for those who lived through it. The hospital personnel could not have anticipated the thousands of casualties that came through their tents in the months of November and January 1942-1943. The painful lessons learned, and the progress made in medical technology, helped to save thousands of lives in later battles and future wars.

In fact, the Portable Army Surgical Hospital was so successful that it was adopted on every front of the war where Americans fought. During the Korean War the name of these medical units was changed to the more familiar Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (M.A.S.H.), made famous by the movie and television series.

My dad was in the 1st Army Portable Surgical Hospital from August 1943 (in New Guinea) until after VJ day (Leyte and Luzon, Philippines). He was an enlisted man, a Sgt. T/3, and was both a ward master and also a surgical assistant. I’m putting together a history of his travels with the 1st PSH and am having a hard time finding very much specific to the 1st PSH. My dad did take a few photos in-country which I possess, one of which he and others of his outfit are next to the 1st Army PSH sign which includes all the major battles they participated in, both in NG and Philippines. If you know of any links to any information specific to the 1st Army PSH, I’d deeply appreciate it. If you would like a scan of the photo I mentioned, I would be happy to send. Thanks, and thanks very much for this nice article to which I’m replying. –Paul L, Saginaw MI [email protected]

I am writing a book on my father’s life, with emphasis on his service in WWII in the South Pacific. He was with the Army’s 1462nd Engineer Maintenance Company from 1943-45. While in New Guinea, he contracted malaria and nearly died. He spent several months recovering in a Portable Surgical Hospital (PSH) and later on a hospital ship. He did rejoin his company in the Phillippines in 1945 and became part of the Occupation Army in Japan after their surrender. My father was Woodrow F. Nelson (1913-1993).

I am looking for personal stories and testimonies from family members and friends of soldiers who were also impacted by diseases in the Pacific theater during WWII – for possible inclusion in my book. If you have any stories to share, please send them to me at [email protected]

Many thanks,

Rich Nelson

Muskegon Michigan

My Father, H.L. Riva commanded the 28th Portable Surgical Hospital in China during WW II. My parents wrote every day. There are over 1300 letters between them. We have the majority of these letters. Hers were the Diary of a war bride with two small children. His the chronicles of a combat surgeon.

It’s taken almost ten years to transcribe, research and document their story. A book is in the process.

Any additional information is welcomed.

My dad was assigned to a hospital unit in the near the front when the battle of the bulge broke out. He was a refrigeration engineer. He would never talk about the war. Don’t know what unit he belonged to so I can’t track its history.

Same with my wife’s step dad. He was a second gen Japanese American. He and his his family were locked up in a California concentration camp. He joined the Army when he turned 18 and fought in Europe in an artillery unit. And, yes, he did receive the ten grand the government to camp survivors, along with a letter of apology.