By Allyn Vannoy

As the Allied armies advanced across Western Europe in the summer of 1944, the First Canadian Army undertook the task of clearing the coastal areas and opening the Channel ports. Fighting on the left flank of the Allied forces, the Canadians pushed rapidly eastward through France toward Belgium. The II Canadian Corps reached Ostend, Bruges, and Ghent in the middle of September.

After Allied forces landed in France on D-Day, June 6, the British Second Army pushed forward into the Low Countries and captured Brussels and Antwerp, the latter with its excellent port facilities intact. But the British advance halted with the Germans still controlling the Scheldt Estuary, a waterway running 50 miles from the North Sea to Antwerp. By September, it had become urgent for the Allies to open Antwerp to shipping in order to ease logistical burdens on their supply lines, which now stretched hundreds of miles back into Normandy.

American General Omar Bradley urged Allied commander in chief General Dwight D. Eisenhower to pressure the British. “All plans for future operations always lead back to the fact that in order to supply an operation of any size beyond the Rhine, the port of Antwerp is essential.” Eisenhower agreed, telling British commander General Bernard Montgomery: “I insist upon the importance of Antwerp. As I have told you I am prepared to give you everything for the capture of the approaches to Antwerp, including all the air forces and anything else you can support.”

The British XXX Corps, after taking Antwerp, could have easily driven the additional 20 miles north and cut off German positions along the inlet to the port. The estuary itself was lined with German forces, including heavy coastal batteries on Walcheren Island that prevented Allied ships from approaching the Scheldt. During the first three weeks of September, however, the German Fifteenth Army withdrew, pulling off something of a minor miracle by extricating nearly 86,000 troops from possible encirclement south of the estuary, using boats and rafts to evacuate them northward across the Scheldt.

The Allies did nothing to open the port of Antwerp during September, instead allocating most of their resources to Operation Market Garden, an ambitious plan to mount a lightning thrust into the heart of the German homeland. The ensuing battle at Arnhem resulted in the near destruction of the British 1st Airborne Division after relief forces from British XXX Corps failed to reach them before heavy counterattacks by German armored units threatened annihilation. Market Garden was a disastrous failure.

At the same time, First Canadian Army completed the clearing of French and Belgian Channel ports by October 1. The force, under the temporary command of Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds, included the II Canadian Corps, the Polish 1st Armored Division, and the British 49th and 52nd Infantry Divisions under Maj. Gen. E.H. Smith. After Market Garden failed, the often stubborn Montgomery was more inclined to listen to American advice. The First Canadian Army was dispatched to bring the Scheldt Estuary under its control. But the remaining German defenders were prepared as always to fight an effective delaying action. Complicated by waterlogged terrain, the ensuing Battle of the Scheldt would prove to be an especially grueling campaign.

To Open the Scheldt Estuary

North of the estuary lay the island of South Beveland, which was joined to the mainland by a narrow isthmus. Beyond South Beveland, to the west, was the island of Walcheren, a fortified German stronghold. Much of the area was below sea level, comprising polder land that had been reclaimed from the sea. Large raised embankments kept the waters from flooding the low-lying land. The German defenders skillfully exploited these conditions. In addition, the Germans constructed bunkers in the steep rear slopes of the dikes and located much-feared Nebelwerfer rocket launchers immediately behind them.

The plan for opening the Scheldt Estuary involved a succession of operations. The first task was to clear the eastern approaches to the Scheldt River north of Antwerp as far as the village of Woensdrecht. This would isolate the German forces on South Beveland from the Dutch mainland. Next step was to eliminate German positions north of the Leopold Canal and south of the estuary—the so-called Breskens Pocket. The capture of 19-mile-long South Beveland was to follow. The final phase of ground combat would be the capture of Walcheren Island, after which Royal Navy minesweepers could undertake operations to clear German mines from the waterway and enable Allied supply ships to pass safely through the estuary to Antwerp.

As a prelude to the coming battle, the Polish 1st Armored Division advanced northeast from Ghent in late September. Against stiffening resistance the division reached the coast on September 20, occupying the town of Terneuzen and clearing the south bank of the Scheldt east to Antwerp. On September 21, the 4th Canadian Armored Division moved north roughly along the line of the Ghent-Terneuzen Canal, with orders to clear the south shore of the Scheldt around the town of Breskens. The division advanced from a hard-won bridgehead over the Ghent Canal at Moerbrugge, becoming the first Allied troops to confront the formidable obstacle of the Leopold and Dérivation de la Lys Canals.

The Algonquin Regiment of the 10th Infantry Brigade, from North Bay, Ontario, mounted a night attack across the Leopold Canal on the Belgian-Dutch border in the vicinity of Moekerke, but the assault force was nearly wiped out in a German counterattack. Those who survived swam back to the Belgian side of the canal and were placed in reserve.

“Black Friday”

The Germans placed a priority on holding Woensdrecht, thus controlling access to South Beveland and Walcheren Island. Infanterie Division 346, under General Erich Diestel (replaced on October 16 by General Walter Steinmüller), was in line north of Antwerp. The division had taken a beating during Operation Goodwood on July 18, coming under intense aerial bombardment. It then had avoided encirclement in the Falaise pocket, retreating across France and Belgium into Holland with only a few howitzers and 2,500 men. Elements of Sturmgeschütz Brigade 280, equipped with heavy assault guns, provided support for the division.

The German high command ordered the Army reserve, Infanterie Division 85, under General Kurt Chill, to bar access to Walcheren by holding Woensdrecht. The division consisted of remnants of two grenadier regiments, elements of Parachute Regiments 2 and 6, and Training and Replacement Regiment Hermann Göring. It was reinforced by remnants of Army Assault Gun Brigades 244 and 667. The Germans had established positions on the little available high ground, Woensdrecht ridge and the railway dike passing through Beveland to Walcheren Island. German guns and paratroopers had dug in along the top of the dike road.

On October 2, the 2nd Canadian Division began its advance north from Antwerp to clear the choke point of the South Beveland peninsula. For the first four days the division made good progress, advancing nine miles to capture Putte, with the base of the peninsula just five miles distant. The 4th Canadian Armored Division moved up to cover 2nd Division’s eastern flank, freeing forces for a renewed drive toward the base of the peninsula. During the next 10 days, the Canadians managed to secure a tenuous foothold on the peninsula west of Woensdrecht.

For the Canadians, attacking the German positions with understrength infantry regiments, a squadron of tanks, and artillery regiments that had to ration ammunition was not an inviting prospect. The operation, code-named Angus, called for 5th Brigade to employ one regiment to seize the railway embankment, with two others passing through to seal off the route to Walcheren Island. The first phase of the assault was to be undertaken by the understrength Black Watch Regiment in a daylight assault.

Heavy casualties resulted as the Canadians attacked over open, flooded ground. Driving rain, booby traps, and enemy land mines made the advance even more difficult. For the Black Watch, October 13, became known as “Black Friday,” the second-worst single-day disaster in the history of the regiment. In an unsuccessful assault on a topographical feature known ominously as “the Coffin,” 56 Black Watch soldiers were killed and another 27 were taken prisoner. All four company commanders were killed, and one company of 90 men was reduced to just four survivors.

Preparing For Operation Switchback

After the debacle of Black Friday, Canadian commanders decided that a night attack was needed. The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry was selected to assault Woensdrecht on October 16. The unit was blessed with seasoned company commanders and veteran noncommissioned officers, and the attack had the support of three field and two medium artillery regiments. By noon on October 17, the Royal Hamilton Infantry had captured the village and the high ground beyond, but German defenders launched repeated counterattacks. Bitter fighting raged for five days, costing the Royal Hamiltons 21 killed and 146 wounded. The Canadians held on to their hard-won gains.

While Simonds concentrated his forces at the neck of the South Beveland peninsula, the 4th Canadian Armored Division moved north and took Bergen-op-Zoom on the Dutch shoreline, further protecting the flank of the 2nd Division. To the south of the Scheldt, German Infanterie Division 64 held a 25-mile sector that ran west along the Leopold Canal from the Braakman Inlet to the historic town of Zeebrugge. The division, formed as an emergency measure after the collapse of German forces in Normandy, consisted mainly of men on leave from the Eastern Front. Thrown into the line in August 1944, it fought in the subsequent battle for the Albert Canal and was isolated when the Fifteenth Army was forced to withdraw.

On October 2, the German division commander, General Kurt Eberding, with 2,350 infantry plus 8,500 support and service personnel and six coastal artillery pieces, prepared to meet the Canadian assault. The Germans had deliberately breached the dikes, and the ensuing flooding channeled the Canadian advance onto the area’s few raised dike roads and polder land.

The next day, Maj. Gen. D.C. Spry’s 3rd Canadian Infantry Division initiated the second phase of the Scheldt campaign, code-named Operation Switchback, to reduce the Breskens Pocket. The 3rd Division encountered tenacious German resistance as it fought to cross the Leopold Canal. It was decided that the best place for an assault would be immediately east of where the Leopold and Dérivation de la Lys Canals split—a narrow strip of dry ground only a few hundred yards wide at its base beyond the Leopold Canal. The plan was for the Canadians to cross the canal, drive straight north to the coast, eliminate the key German gun battery at Cadzand, capture the port of Breskens, and move east, eliminating German gun batteries there.

On the night of October 5, the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment of the 8th Brigade brought forward canvas assault boats, carrying them over the fields and placing them along the slope of the dike to their front. When the signal came, they could grab the assault boats, carry them over the top of the dike, and throw them into the water.

Operation Switchback Begins

The next morning the assault commenced, with the 3rd Division’s 7th Brigade, along with the North Shore Regiment, making the initial assault across the canal near the town of Eede. German positions in the area included concrete bunkers reinforced with logs, with good fields of fire across the canal. Roads leading north from the rear of the German positions were covered by machine-gun fire.

The assault of the 7th Brigade was supported by artillery and Canadian-built Wasp troop carriers, which were equipped with flamethrowers to deliver a barrage of flame across the Leopold Canal. With screaming Germans lit up like torches running into the trees on the opposite shore, the attackers scrambled up the steep banks and launched their assault boats.

Only half of the troops made it to the far side and established two precarious footholds. The Germans, dug in on the rear slope, managed to recover from the shock of the flamethrowers and counterattacked repeatedly for the next 48 hours, but they were unable to drive the Canadians from their vulnerable bridgeheads. The Canadian infantry soon discovered that they could not dig foxholes more than a foot deep before the holes filled with water. Adding to their problems, close air support was hampered by poor weather. By October 9, however the gap between the bridgeheads was closed.

The flooded polder land beyond the dike made maneuvering extremely difficult. Any movement along the roads leading north came under intense enemy fire. After six days of fighting, the Canadian commanders, having suffered nearly 600 casualties, realized that they needed to find another way to get to the coast. Orders were given to withdraw. Meanwhile, the 9th Infantry Brigade mounted an amphibious attack on the coastal side of the pocket, sweeping west of the mile-wide Braakman Inlet. The brigade used Terrapin and Buffalo amphibious vehicles, crewed by the British 5th and 6th Assault Regiments of the Royal Engineers, to carry them across the mouth of the inlet to land in the vicinity of Hoofdplaat and exert pressure from two directions on the German defenders along the inlet. Mortars laid down a heavy smoke screen as the Canadians made their way across marshland and over dikes.

The Canadians took the German defenders by surprise and quickly established a bridgehead. Once again, the Germans recovered quickly and counterattacked with ferocity, but they were slowly forced back. General Spry moved his remaining force, the 8th Brigade, into the bridgehead. Attacking west, the Canadians took Biervliet and Hoofdplaat on the coast. Seeing the eastern flank of their defenses unhinged, the Germans withdrew to a second line of defense that ran from Breskens along the Sluis Canal to Zeebrugge. Meanwhile, RAF Bomber Command mounted heavy strikes against German gun batteries at Breskens and Flushing.

Cornering the Germans on Walcheren

The second phase of Operation Switchback started on October 21 with a successful assault on Breskens. The 9th Brigade cleared German troops from the towns of Schoondijke, Oostburg and Zuidzande. The coastal bastion of Fort Frederik Hendrik held out for three more days before its garrison surrendered. Cadzand, where the Germans had their largest gun emplacement along the southern side of the Scheldt, fell on October 27. The 3rd Division completed Operation Switchback two days later, overwhelming the last German resistance in the Belgian coastal towns of Knocke and Zeebrugge, southwest of the pocket. Some 29 days of fighting had cost the Canadian division 2,077 casualties. During the fighting, some remnants of Infanterie Division 64 managed to escape north across the estuary to South Beveland.

With the Breskens Pocket cleared, the Allies could now use it as a staging area for the attack on Walcheren. Amphibious vehicles landed at the port of Breskens, and the Allies positioned supporting artillery in the low-lying area to the south. The 2nd Division began its westward advance down the South Beveland peninsula from its hard-earned gains at Woensdrecht. After a heavy artillery bombardment, the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade began to fight its way west. By dawn the following day, it had advanced three miles to capture Rilland. Throughout the remainder of the day, the brigade closed on the town of Krabbendijke. The Canadians hoped to advance rapidly, bypassing opposition and seizing bridgeheads over the Beveland ship canal, which bisected the peninsula, but they were slowed by mines, mud, and strong enemy defenses.

In support, other Allied forces launched Operation Vitality II to outflank German defenses at the eastern end of the peninsula. A Royal Navy landing craft, supplemented by Buffalo and Terrapin amphibious vehicles, carried elements of the British 52nd (Lowland) Division across the Scheldt. Sailing from Terneuzen, the amphibians of the 1st Assault Brigade, Royal Engineers, advanced eight miles across the estuary to South Beveland, west of the ship canal. Spearheaded by amphibious DD (Duplex Drive) Shermans from the Staffordshire Yeomanry, the force established a beachhead near Hoedekenskerke.

On October 26, the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade began a frontal attack on the canal head in assault boats. Engineers were able to bridge the canal along the main east-west road. By October 29, the Canadians had captured the town of Goes and linked up with the 52nd Division. With the canal line cleared, German resistance crumbled on South Beveland. Remnants of some German units managed to withdraw to Walcheren Island. The final phase of the Battle of the Scheldt was about to begin.

The Defenses of Walcheren

The enemy defenses on Walcheren Island were extremely strong, with heavy coastal batteries posted on the western and southern coasts. The coastline itself had been fortified against amphibious assaults, and a landward-facing defensive perimeter had been built around the town of Vlissingen to defend its port facilities should an Allied landing on Walcheren succeed. The only land approach was the Sloeda, or Walcheren, Causeway—a thin strip of ground a few yards wide joining South Beveland to Walcheren Island over the Sloe Channel. The causeway was little more than a raised two-lane road. To make matters even more difficult for attackers, the flats that surrounded the causeway were too saturated with sea water for movement on foot or in vehicles, but were too shallow for assault boats. The defenses had been attacked by Bomber Command and 2nd Tactical Air Force in September, but poor weather and heavy antiaircraft fire had reduced the effectiveness of the air strikes.

Walcheren Island was garrisoned by Infanterie Division 70, under 60-year-old Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Daser. The unit was a “white bread” or magen (stomach) division made up of men with special dietary needs. Some were recovering from stomach wounds, others had digestive problems such as ulcers and could not tolerate the normal, heavy German flour. The Germans had grouped the sufferers together in August 1944 and assigned the division to safeguard the Dutch coast at Zeeland. Despite their shortcomings, the ailing soldiers performed surprisingly well. Also on Walcheren Island were naval personnel of the 202nd Marine Artillery Battalion.

Gaining a Foothold

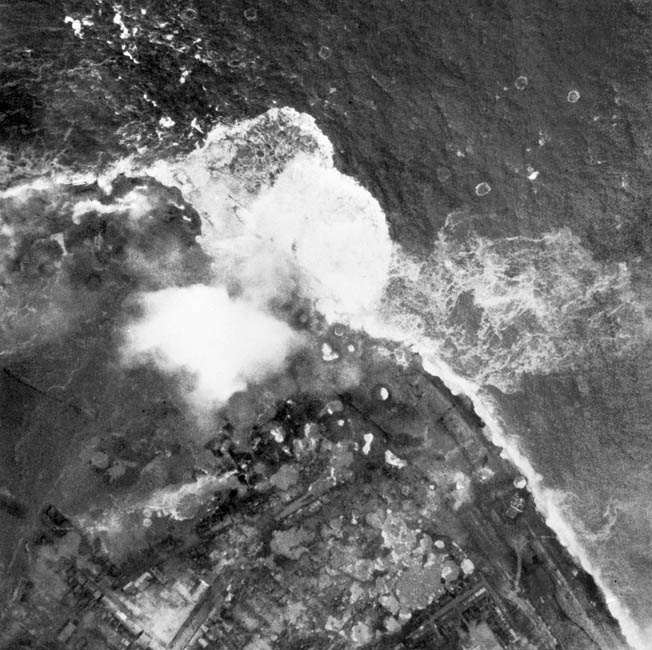

To weaken the German defenses, Allied bombers mounted five separate attacks involving some 494 sorties against the island’s perimeter dike. The bombing breached the dike in four places, and the sea poured into the interior of the low-lying island, flooding four-fifths of the area. Between October 28 and 30, Bomber Command mounted a further 745 sorties against German defenses, dropping more than 4,000 tons of bombs and destroying 11 of the enemy’s 28 artillery batteries.

The island was to be attacked from three directions—from the east, across the Scheldt from the south, and by sea from the west. It was hoped that the German defenders would not be able to respond effectively to these multiple assaults. The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division’s already bloodied 5th Brigade attacked the causeway from South Beveland on October 31. The initial attack by the Black Watch was rebuffed. The Calgary Highlanders then sent a company, which was also stopped halfway down the causeway.

An attack by the Highlanders on the morning of November 1 managed to gain a precarious foothold, but a subsequent German counterattack drove the Canadians back onto the causeway. A day of fighting followed, with the Highlanders relieved by Le Regiment de Maisonneuve, which struggled to maintain the bridgehead. The “Maisies” withdrew onto the causeway on November 2 and were relieved by a battalion of the Glasgow Highlanders of the British 52nd Division.

On November 3, other lowland units crossed the Sloe Channel south of the causeway in boats to outflank the German defenses. Within 24 hours the division had established a sizable bridgehead along the island’s unflooded eastern fringes.

Capturing Flushing

The second element of the assault on the island began shortly after midnight on November 1, as landing craft and amphibious vehicles, part of Force T, departed Ostend and headed northeast. Carrying troops from 4th Special Service Brigade under Brig. Gen. G.W. Leicester, Royal Marines, the landing force was to launch an amphibious assault on the westernmost point of Walcheren at Westkapelle.

Meanwhile, the third assault component, with landing craft and amphibious vehicles, under cover from a bombardment of artillery around Breskens, departed Breskens for Flushing—code-named “Uncle Beach.” This was Operation Infatuate I and consisted mainly of infantry of the British 155th Infantry Brigade—4th and 5th Battalions, King’s Own Scottish Borderers; 7/9 Battalion, Royal Scots; and the No. 4 Commando. At 5:40 am, the commandos assaulted the heart of Flushing’s harbor area, with troops of the 4th King’s Own Scottish Borderers landing at 7:30. Within the town, Dutch resistance groups also began to attack German positions supported by artillery and Typhoon fighter-bombers. British troops, along with French commandos, gradually fought their way through the town.

The next day, the Allied troops pushed their way to the northern edge of Flushing, again aided by artillery and Typhoons. That night the 7/9 Royal Scots attacked the Hotel Britannia, a center of German resistance southwest of the town. Despite finding themselves wading through water five feet deep in the dark, the Royal Scots pressed home the attack. When the 600 defenders surrendered around noon on November 3, Flushing was finally cleared of enemy forces.

The Assault on Westkapelle

The force destined for Westkapelle—Operation Infatuate II—had moved northeast during the early hours of November 1. At 8 am, the German coastal batteries engaged the landing force, with the battleship HMS Warspite and the monitors HMS Roberts and Erebus returning fire. At 8:45, Allied artillery from Breskens added its weight to the bombardment.

During the approach to the beaches, at least one LCT was disabled and a rocket support launch was hit and set off an amazing fireworks display that damaged several other craft. Lt. Col. J.B. Hillsman of the 8th Surgical Unit observed the sinking of one of his unit’s craft. “We were getting close in now and the landing craft tank in front of us turned out of line to further back,” Hillsman recalled. “As it passed us, it struck a sea mine. There was tremendous explosion and the ship was hurled into the air. It settled rapidly. Men jumped into the sea. Some were picked up by the following craft. Others floated face down in their life belts.”

The first assault troops of the 4th Special Service Brigade landed at 9:59 am. Within 30 minutes, the bulk of No. 41 (Royal Marines) Commando was ashore, as were elements from No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando, which consisted mainly of Belgian and Norwegian troops, and No. 48 (Royal Marines) Commando, supported by specialized armored vehicles—amphibious transports, mine-clearing tanks, and bulldozers—of the 79th Armored Division. These forces landed at Red and White Beaches, respectively, located to the north and south of the breached dike just to the south of Westkapelle.

To ensure that the landing would be successful, 27 armed landing craft of the Support Squadron Eastern Flank engaged the German batteries in the area, seeking to divert their fire from the assault troops. They achieved hard-won success, but only seven of the craft survived undamaged and another 370 casualties was suffered by the squadron’s sailors and marines.

During that morning, the commandos fought their way through Westkapelle in the face of fierce resistance. Subsequently, No. 41 Commando advanced north along the narrow, unflooded coastal strip toward Domburg, which was secured before dusk. Meanwhile, No. 48 Commando had advanced southeast toward Zoutelande, with No. 47 Commando landing later that day. By nightfall, the 4th Brigade had secured a six-mile strip of coast and now had three complete Commandos, plus two French troops of No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando ashore.

The Campaign’s Last Stages

On the morning of November 2, No. 48 Commando captured Zoutelande, taking 150 prisoners in the process. Two days later No. 47 Commando linked up with No. 4 Commando advancing northwest from Flushing. Three days later, the 11th Royal Tank Regiment, along with the Royal Scots, advanced northeast through the island’s flooded interior to Middelburg, using their remaining 11 operational Buffaloes. Simultaneously, the 5th’s Calgary Highlanders struck west from the bridgehead secured on the unflooded eastern flank of Walcheren by the 52nd Division. The German defenders were taken by some surprise. General Daser, the German commander, was reported to be considering surrendering, but only to an armored force.

As it was impossible to reach the water-logged town with tanks, a calculated gamble was made to drive amphibious Buffaloes into Middelburg. Faced with the heavy Allied armament, Daser relented, and in the hours that followed the small British force found itself guarding a much larger number of disarmed Germans. Later that day, Veere, in the northeastern corner of the island, surrendered to the 158th Brigade, but enemy forces continued to hold out along the northern coast. By November 7, however, No. 41 Commando and French Commandos overwhelmed the last pocket of enemy resistance.

In the final stage of operations to open Antwerp, a large-scale minesweeping operation of the estuary—Operation Calendar—was undertaken from November 3 to 25, collecting 267 mines. Thus cleared, the first Allied ship, the Canadian-built freighter Fort Cataraqui, arrived in Antwerp on November 28. The Battle of the Scheldt Estuary was over.

2.4 Million Tons of Matériel

In the course of five weeks of often savage fighting, the First Canadian Army took 41,043 Germans prisoner, while suffering 12,873 casualties, 6,367 of whom were Canadians; the remainder were from British and Polish units. The 2nd Canadian Division alone lost 3,650 men in 33 days of intense battle across the isthmus and west to Walcheren Island. The importance of the port was made apparent when the Germans selected it as a key objective in the coming winter offensive known as the Battle of the Bulge. According to one estimate, the two-month delay in opening Antwerp cost the Allies some 2.4 million tons of additional matériel—supplies that were sorely missed during the autumn fighting across northern France and Germany.

I would not in any way diminish the effort at Antwerp but in terms of total casualties, including civilian, I would have to say that the battle for Manila in Feb-Mar 1945 that resulted in over 200,000 dead was probably the toughest urban battle after the Battle of Stalingrad. The nature of Japanese resistance at Manila and the Soviet mass attacks at Stalingrad, both of which trapped hundreds of thousands of civilians, were illustrative of urban warfare.