Warfare brings about great deeds and dire circumstances. In the aftermath of the world’s greatest conflicts, some soldiers and commanders become footnotes in the history books, whereas others are able to rewrite the book itself.

Here is a brief list of our badasses of history: leaders and the commanders who, for good or ill, changed the course of world events forever.

“Yasha” Botchkareva and the Battalion of Death

In May 1917, Duma (the Russian parliament) President Mikhail V. Rodzianko summoned Maria “Yasha” Botchkareva, a Siberian peasant, to St. Petersburg to hear her plea to organize a women’s battalion for the coming summer offensive. During her lifetime, Botchkareva had fled from her drunken and abusive husband, enlisted in the Russian Imperial Infantry, suffered two wounds in combat, and won three decorations for bravery under enemy fire.

“You heard of what I have gone through and what I have done as a soldier,” Botchkareva stated to Rodzianko’s assembly of soldiers’ delegates to the Duma. “Now, how would it do to organize three hundred women like me to serve as an example to the army and lead the men into battle?”

Botchkareva later recalled that she was granted authority then and there to form the First Russian Women’s Battalion of Death.

Howard W. Gilmore

On February 7, 1943, while on patrol in the South Pacific, U.S .Navy Commander Howard W. Gilmore, commander of the USS Growler and his crew carved out a place for themselves in navy legend, and set a standard of duty that is remembered in the submarine service today.

Growler had departed Brisbane, Australia, on January 1, 1943, to partrol shipping lanes between Truk and Rabaul in the Bismarck Islands, off the northeastern coast of New Guinea, an area that was bristling with Japanese aircraft and armament.

On the night of February 4, Growler spotted a Japanese convoy of merchant ships with two patrol boats as escort. Opting for a surface attack, Growler slipped through the darkness to get a head of the Japanese ships.

What happened next made submarine and military history.

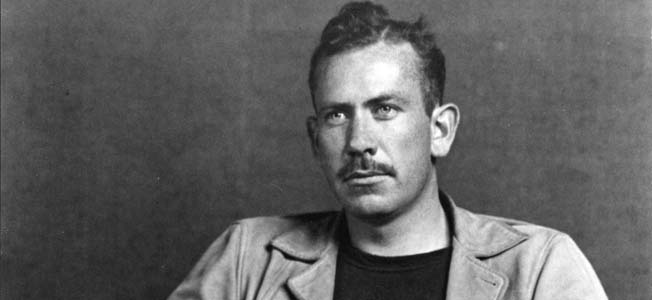

John Steinbeck

A fuming John Steinbeck vented his frustration over World War II to a friend on March 15, 1943. Employed by the government in home front duties, the Pulitzer Price-winning author of The Grapes of Wrath expected a big military push to come soon, and he wanted to be overseas, not stateside, covering the war.

As an accredited journalist, Steinbeck could still write and yet be in the thick of the fighting. But his temper flared as he told his friend, “From what I have so far, if I go into the army I would prefer to be a private. The rest is very like the fraternity system at Stanford. I have not been notified of rejection by the way.”

He would get his wish and more, participating in the Salerno invasion and serving alongside a special commando unit that would enable him to blur the role of journalist and soldier.

Louis XIV: The Sun King of France

Louis XIV of France is remembered as the Sun King, the most resplendent figure of his age, the man who snatched dominance of Europe from the Spanish and built France into the preeminent power of the second half of the 17th century.

His first main venture into guiding military affairs would be well plotted and practically assured of success; it was the conquest of Spanish Flanders. First, Louis made sure he had the money to pay for the venture—his minister Colbert saw to it that the coffers were adequately filled. Louis also made much of organizing and retraining his soldiers, weeding out incompetent commanders. And he waited until his prey was weak—the Spanish empire was in decline and in the year 1666 Spain had a five-year-old sickly king, Charles II.

Even this was not enough. Louis claimed that where he was sending his army was by right his anyway. The argument revolved around six-year-old clauses of his marriage to Marie Therese—the late King of Spain Philip IV’s daughter—and the argument had some validity. Moreover, Louis made a treaty with Portugal so that he could attack Spain through this country if the conquering grew complicated in Flanders. Not even all this was enough; he also bribed German princes into neutrality. And he waited until his own army vastly outnumbered Spanish forces in Flanders. Then he gave military command of the campaign to his most experienced general, Turenne.

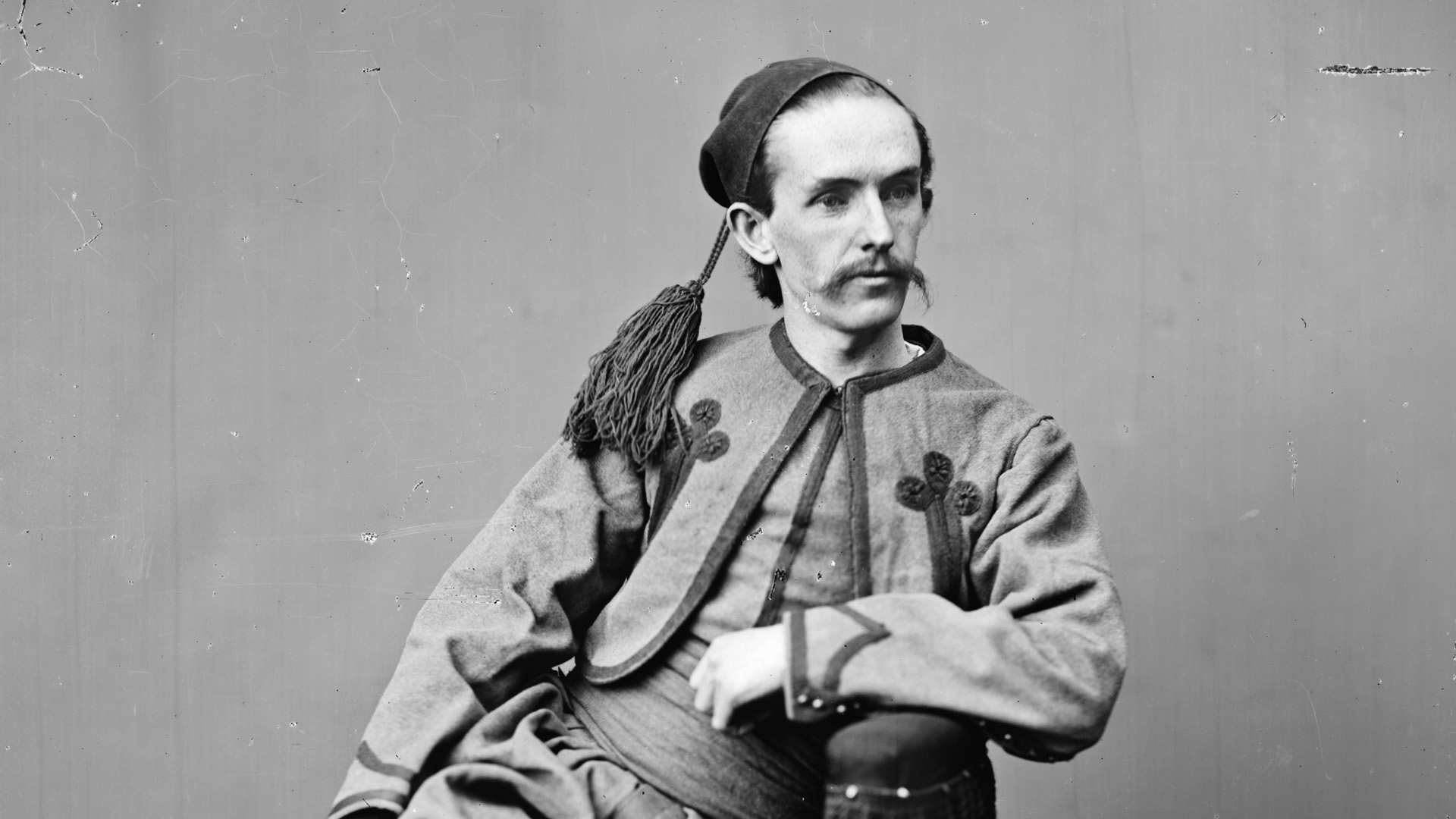

William B. Hazen: The Civil War’s “Best-Hated Man”

In the course of his 30-year military career, William Hazen managed to quarrel with various superior officers, up to and including the president of the United States.

He was reprimanded, court-martialed, and removed several times from command, only to be restored when political allies such as Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield entered the White House. His courageous testimony in the trading post scandals surrounding Secretary of War William Belknap resulted in the secretary’s resignation in disgrace but earned Hazen the lasting enmity of Belknap’s patron, President Ulysses S. Grant, and Grant’s minions, including Generals William T. Sherman, Phil Sheridan, and George A. Custer.

For Hazen, this was all in a day’s work.

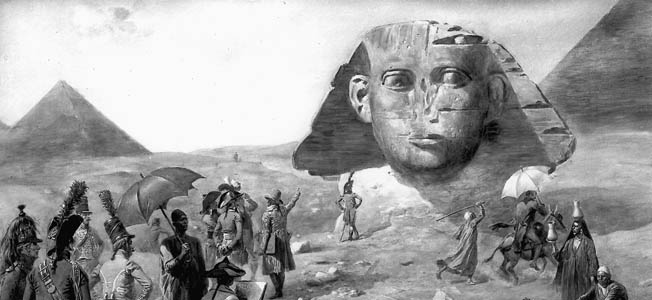

Alexander the Great: The “Unstoppable God of War”

Alexander III became King of Macedon at the age of 20 in 336 B.C., upon the assassination of his father, Philip II. In the spring of 334, having spent the last two years settling things in Macedonia and Greece, Alexander set out for the Hellespont to fulfill his father’s plan to bring war to the Persians. The undertaking was made possible by the standing army Alexander had inherited from Philip.

In 334 B.C., at age 22, he met the Persian army at Arisbe, marched east to defeat the Persians in bloody hand-to-hand combat at the Granicus River, and then turned south along the coastline, taking the coastal cities. The Macedonian king then wanted to visit the temple of Jove to see the famous Chariot of Gordion.

There, he made history.

“Mad Jack” Churchill

It was May 1940, and the German officer’s unit was attacking toward a village called l’Epinette, near Bethune, France. Five of his soldiers took cover behind a farmyard wall, sheltered from the fire of British rearguards covering the retreat of the British Expeditionary Force to the English Channel. Without warning, one German crumpled, the feathered tip of an arrow sticking out of his chest. From a small farm building on their flank, rifle-fire tore into the others.

While he may have known that his enemy was soldiers of the Manchester Regiment, the German leader could not have known that they were led by the formidable Captain Jack Churchill. It was Churchill’s arrow that skewered the luckless German, while his men’s rifles accounted for the rest. However deadly, bows and arrows were surely anachronisms in modern war. They were formidable soldiers and always had been, precisely the sort of men Jack Churchill was cut out to lead.

But then, so was the bowman.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments