by Robert Suhr

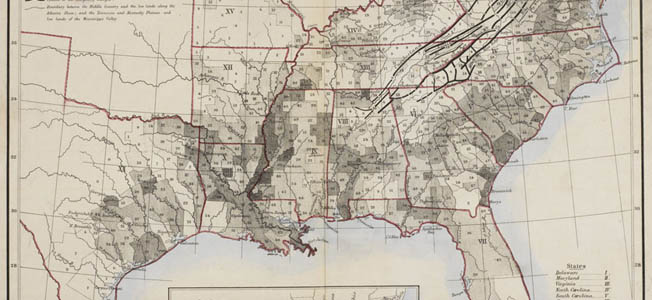

In late September 1861, the Union navy moved to the Head of the Passes. From there, below New Orleans, the Mississippi River divided into three major passes leading to the Gulf of Mexico. Efforts to blockade the river from outside the passes had been only partially successful. From the Head of the Passes the Union sailors had a stranglehold on commerce in and out of the river.

Captain “Honest John” Pope commanded the detachment from his flagship, the Richmond. Besides this 22-gun steam sloop, he had the 20-gun sailing sloop Vincennes, the 16-gun sailing sloop Preble, and the 3-gun paddlewheel Water Witch.

While not impressive in numbers or size, the Union force certainly was stronger than what the Confederates could muster. Besides the rigged-up ironclad Manassas, they had only five steamers that carried 19 guns. But the Southerners were determined to win back Head of the Passes and resume what trade they could out of the South’s largest city.

[text_ad]

Too Late for a Warning

About 3:30 am, the low-riding ironclad reached Head of the Passes. In the darkness, Captain Warley spotted lanterns hung by the Richmond as the crew transferred coal from a schooner. He ordered the pilot to steam toward the lights while the crew stoked the engine to gain as much speed as possible.

A lookout on a captured schooner spotted the Manassas approaching and shouted a warning to the Richmond that no one heard over the noise of the coaling operation. An officer on the Preble saw the ironclad, but it was too late.

At 10 knots per hour the Manassas rammed the Richmond. In severing the hawsers that connected the Union warship to the coal schooner, she lost both smokestacks. The impact damaged one engine.

Union in Retreat

As the Manassas limped away, a midshipman aboard fired the signal rocket for Confederate gunboats to advance. Three fire rafts preceded them down the river, but the wind drove them ashore. Dawn saw the Manassas and one gunboat aground. But the Union was in retreat.

The attack by the Manassas did little damage to the Richmond, but it had the desired effect. The Richmond and the two sailing ships retired from danger. The Water Witch, with the captured schooner in tow, guarded the rear.

At the bar, where the Mississippi finally ends in the Gulf, the Vincennes went aground. With smoke from the Confederate gunboats visible to the lookouts, Pope tried to swing the Richmond about to guard her. He succeeded only in driving his ship aground too.

“A Laughingstock of All and Everyone

Pope was shocked when Commander Robert Handy and the crew from the Vincennes suddenly appeared alongside the Richmond in several boats. Handy had misread a signal from the Richmond that he was to abandon ship. Handy had set a charge near the powder magazine so the vessel would not fall into Rebel hands, but a sailor who did not want to see the ship pulverized cut the fuse. Pope ordered Handy back on the Vincennes. Handy finally got the sloop free by throwing her guns overboard.

Pope soon removed Handy from command, writing, “He is a laughingstock of all and everyone.” Pope himself asked to be relieved of command for “health reasons,” a request that was granted.

After the war, Commander David Porter wrote: “Perhaps this fiasco had a good effect by causing the Confederates to underrate the Northern navy; if so, they dearly paid for it, for only a few months afterwards all their rams, ironclads, fire-rafts and gunboats were swept away.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments