By John F. Murphy, Jr.

With Rommel driving on Egypt and the British pushed out of Greece, a sudden pro-Nazi coup d’état in Iraq lay rich oil fields and more at Germany’s feet.

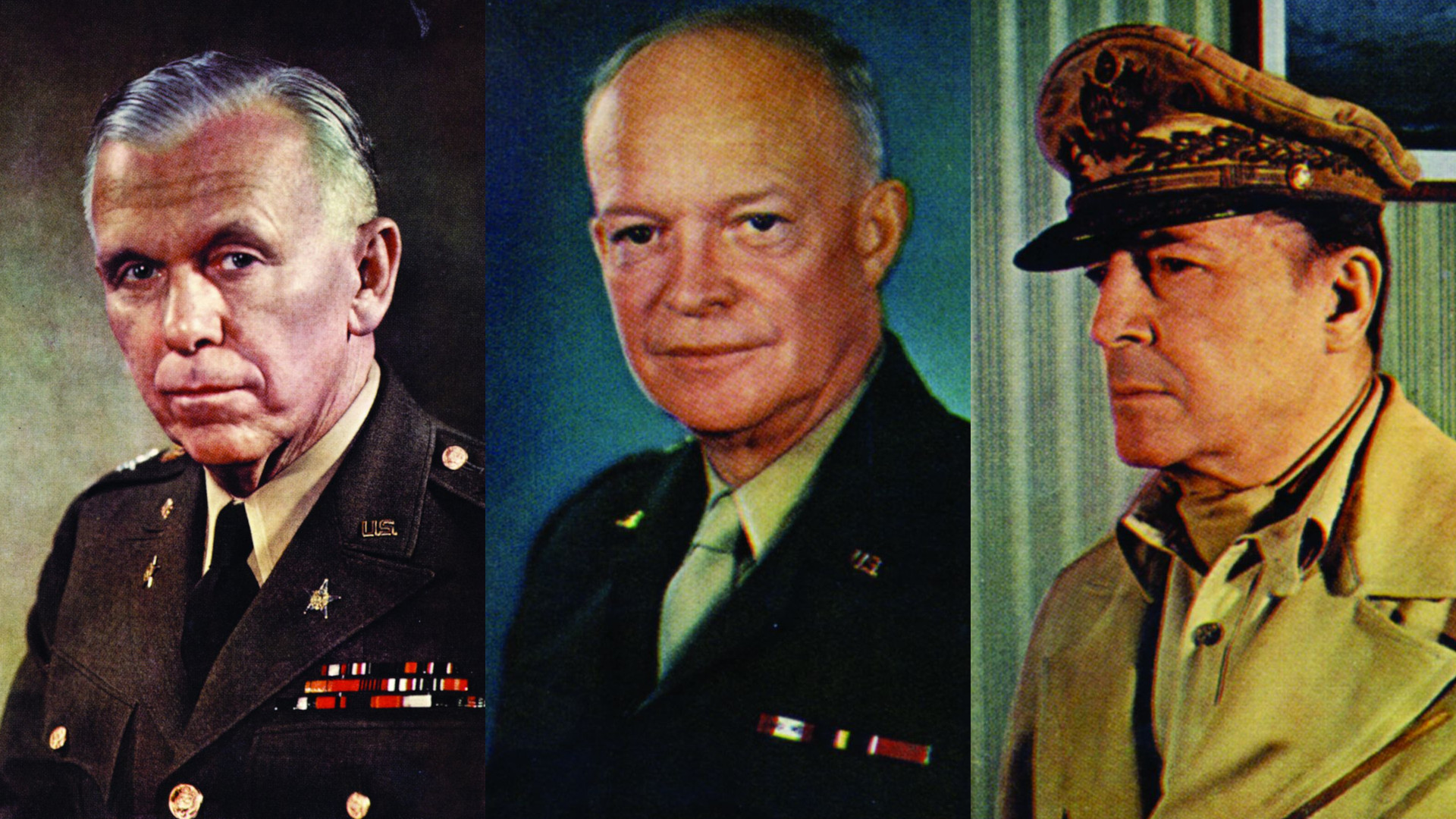

In the spring of 1941, events in the Middle East suddenly exploded in a crisis for Great Britain. On March 24, Lt. Gen. Erwin Rommel, soon to be known as the legendary “Desert Fox,” dealt the British its first defeat by his Afrika Korps at El Agheila in Libya. It was just the beginning. By April 12, Rommel would drive the hard-pressed British Tommies back to the very gates of Egypt itself, threatening the vital Suez Canal. Also in April, the German Twelfth Army would overrun Greece in a lightning three-week campaign, forcing a wholesale evacuation of British forces to the island of Crete only to be ejected once again by a German airborne invasion.

Multiple Implications of the Iraq Putsch

Just as these events were unfolding, a worse blow fell. Iraq’s pro-British government was toppled in a coup in March by the very pro-German Rashid Ali al-Gailani. Iraqi Prime Minister, Nuri al-Said, had to flee for his life. The British Ambassador, Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, was held hostage in the embassy. Rashid Ali made “threats to the Ambassador about cutting the throats of the British if any bombs were dropped on Baghdad,” recalled British officer Somerset de Chair, who would play an important role in the drama to come.

The Iraq putsch was as devastating a blow to England in the Middle East, especially coupled with the Desert Fox’s spectacular victories in North Africa, because Iraq shared an importance, second only to that of Egypt, for the survival of British power in the entire region. The reason for Iraq’s importance to England was simple. Whoever controlled Iraq sat astride the crucial overland route between Egypt and India, the most precious jewel in England’s Imperial Crown. Just as vital, whoever controlled Baghdad, the Arabian Nights capital of Rag, could sever the vital oil pipelines that flowed across the deserts to the Mediterranean and from Iran to the Iraqi Persian Gulf port of Basra, from which fat-bellied tankers carried the precious fuel that was now the very life’s blood of England and her Empire.

Rommel, whose panzer tanks depended on oil, realized the value of the vast oil reservoir of the Middle East. “In 1939,” he wrote, “Persia and Iraq together provided in all some 15 million tons of mineral oil, compared with Romania’s 6.5 million tons.” Romania was the site of the famed German-controlled oil fields of Ploesti, the target of heavy Allied bombing during the war.

Ever since World War I overthrew the power of the Ottoman Turks, having a friendly government sitting in Baghdad had been a cornerstone of British policy. The League of Nations had given Iraq, like Palestine, to England as a mandate—almost a colony, but technically under League of Nations’ supervision. When the famed T.E. Lawrence helped Winston Churchill broker the British settlement of the Middle East, Emir Feisal, Lawrence’s leader in the famed Arab Revolt, was installed in Baghdad as king. To ensure Feisal’s rule (and protect Britain’s interest), the British patrolled the vast Iraqi desert and its Bedouin tribes by Royal Air Force (RAF) planes from above and Rolls-Royce armored cars on the desert floor.

Germany’s Plans for the Middle East

But Rashid Ali al-Gailani’s March 1941 coup, led by the secret “Golden Square” society, had toppled this careful settlement. For Rommel, the possibility of a pro-Axis ruler in oil-rich Iraq was a dream come true. With sufficient support from Hitler (which, good for the Western Allies, never materialized, owing in no small part to the Führer’s preoccupation with the coming attack on the Soviet Union), Rommel saw the Afrika Korps striking through the Middle East to seize the oil fields and then, with plenty of fuel for his panzers, be poised to strike, if needed, the underbelly of Russia.

In his crisp, soldierly prose, the Desert Fox spelled out his campaign plans in a note to himself to be used for post-war memoirs: “We could have defeated and destroyed the British Field Army, and that would have opened the road to the Suez Canal.… With the entire Mediterranean coastline in our hands, supplies could have been shipped to North Africa unmolested. It would then have been possible to thrust forward into Persia [present-day Iran] and Iraq in order to cut off the Russians from Basra [which became a main source of supply for Russia once Hitler invaded], take possession of the oil fields and create a base for an attack on southern Russia.” In short, Rommel’s conquest of the Middle East oil fields “would thus have created the conditions for victory in the Russian plains.”

But the Germans had done more than merely dream of Middle East conquest. The groundwork for the plot had been very carefully laid. German secret agents, spies for the famed Abwehr of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, had carefully infiltrated Iraq, under the very noses of the British, fomenting discontent and building support for their candidate for power, Rashid Ali. Already a base was in readiness next door in Persia, where a sizable German—and pro-Nazi—colony already existed.

Somerset de Chair has left an ominous picture of what was going on inside neighboring Persia. “We soon noticed how the stream of German armaments to Persia, by way of Turkey, had been increasing in recent months.… We examined closely the set-up of the German Fifth Column in Persia, where 4,000 Germans in commercial occupations were organized under Gauleiters [Nazi Party leaders] and could be mobilized on the telephone. At the most recent maneuvers the Persian Army had displayed ninety tanks; and we could not rule out the possibility that Germany was going to ‘borrow’ these from Persia to reinforce the Iraqis.”

Already the German Army had formed two special units trained and ready to assist the Iraqis, the 287th and 288th Brandenburg companies [the 288th was commanded by Colonel Menton, an old friend of Rommel’s from the Great War]. The danger was obvious, and growing worse. It was clear that something had to be done about Rashid Ali in Baghdad. It was in this grave hour that one of the most exciting, and least-known, campaigns of World War II was launched—the story of Kingcol and the British march on Baghdad.

The Launching of ‘Kingcol’ and the Legendary Glubb Pasha

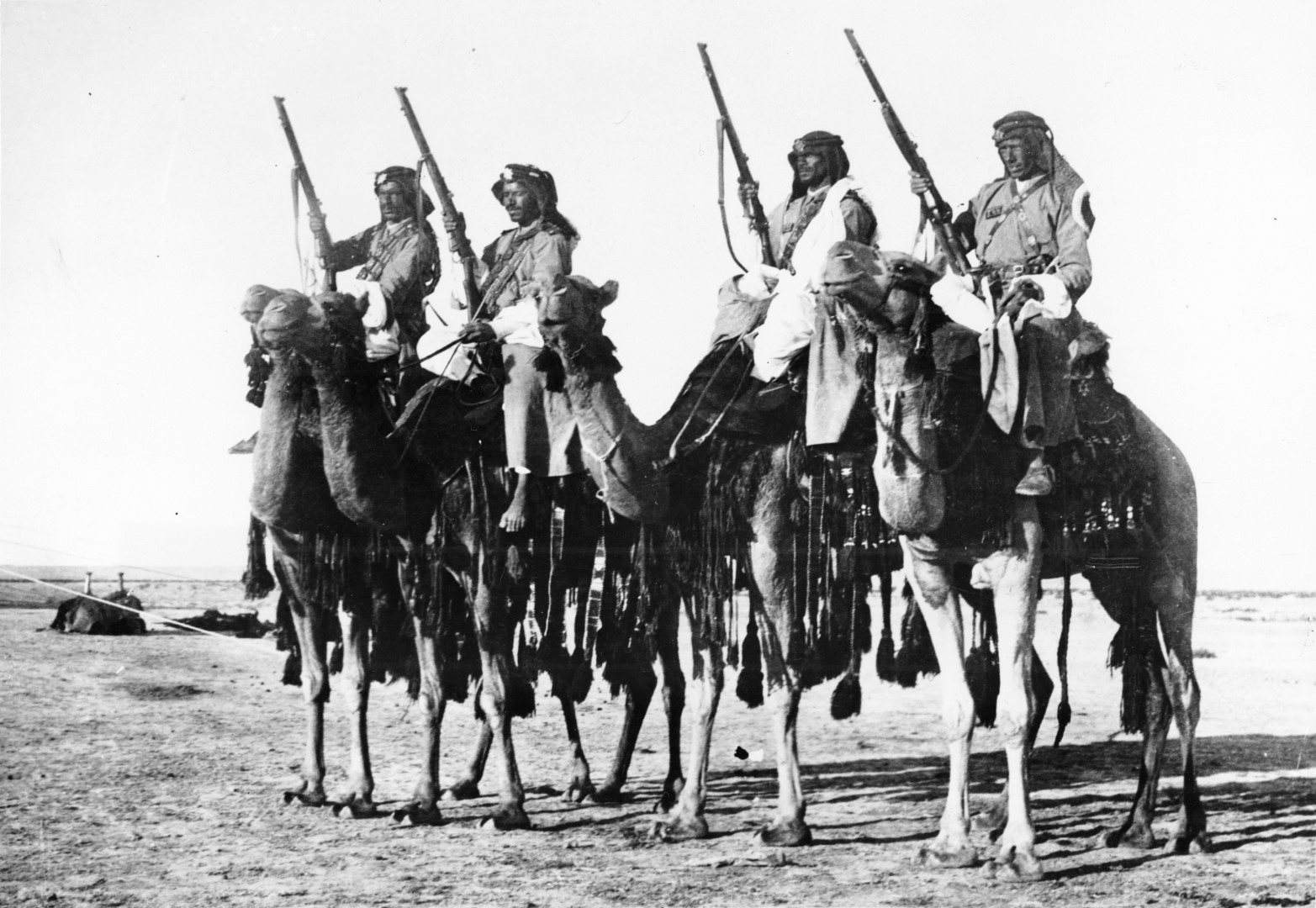

Still facing an Afrika Korps bent on the conquest of the Land of the Pharaohs, the British daringly assembled a strike force for the advance on Baghdad. Commanded by Brig. Gen. Joe Kingstone, whom de Chair said some considered “the best fighting Brigadier in the British Army,” the British force assembling for this Arabian Nights’ adventure was called King Column, or “Kingcol” for short, taking part of its name from part of its leader’s name. A more colorful army had not been gathered together in the Middle East since Lawrence of Arabia, mounted on his fleet racing camels, had marshaled the wild Bedouin to do battle with the Turks.

Massing for the searing 750-mile trek across the desert sands from Palestine were soldiers from some of the oldest regiments in the British Army—baptized under fire with the great Duke of Marlborough—standing beside warriors of some of the most picturesque units mustered to guard the frontiers of Britain’s far-flung empire, now led by Marlborough’s descendant, Winston Churchill. De Chair described this colorful and barbaric cavalcade: “We were a motley crowd. His Majesty’s Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards jostled along in their army trucks beside the Bedouin of the Arab Legion—Glubb’s Desert Patrol, swathed in garish robes, who raced about in light trucks armed with Lewis guns,” like the commandos of David Stirling’s Long Range Desert Group fighting against Rummel farther west.

Of all the array led by the capable Kingstone, none was more exotic than the Arab Legion, nor more legendary than Sir John Bagot Glubb, Glubb Pasha [pasha is an old Turkish title loosely meaning “commander” or “leader”]. Second only to Lawrence in the dramatic history of the British Empire in the Middle East, by this time Glubb Pasha was the warrior sheikh of the Arab Legion. He had taken over command of the Legion in 1939 from F.G. Peake, who had formed the desert corps. During World War I, Peake had first been in the Egyptian Camel Corps, and then had been sent to serve under T.E. Lawrence in the Arab Revolt. After the war, Peake entered the service of Feisal’s brother Abdullah, who ruled as Emir, and later as King, of the Arab state of Transjordan, now part of the Kingdom of Jordan. The Arab Legion was formed to control the Bedouin tribes in his new domain, and to defend it from outsiders.

Under the leadership of Peake, and later Glubb, the Arab Legion soon gained such a bold reputation that Arabs from all over the region flocked to join. Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre have described Glubb Pasha in 0, Jerusalem, their account of the birth of Israel, in 1948. “Yet of all the long line of British Arabists that had followed the master [Lawrence] east, he was indisputably the greatest. No Westerner alive had mastered the intricacies of the Bedouin dialect as completely as Glubb. He could hear a Bedouin’s history in the inflections of his accent and read his character in the folds of his kafriyeh [headdress]. He knew Bedouin lore, their customs, their tribal structure, the complex web of unwritten law governing their lives.”

Kingcol Begins Its March

On May 2, 1941 the Kingcol, burdened with the knowledge of British defeats all through the Middle East, and like a medieval army from the Crusades, began its advance. Out in front were the hawk-eyed Bedouin of Glubb’s Arab Legion scouting for signs of the mutinous Iraqi forces. Soon Somerset de Chair and Kingcol caught up with the Legion at the desert watering-hole of Rutbah, whose 10,000-gallon water tank made it a vital spot for the British to hold in the water-parched sands.

Already the British had fought—and won—the first battle of the war for the possession of this oasis. On May 9 Fawzi Qawukji, the leader of the Iraqi fighters, had defended Rutbah with machine guns and a hundred members of Iraq’s Desert Police, like the Arab Legion armed and trained by the British. (Fifty years later, Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi army would also turn its Western arms and armor against the same Western Powers that had armed it.) The next day, May 10, as Glubb reported to Brigadier Kingstone, Qawukji “fought an action with RAF armored cars, as a result of which he retired east in evening and contact has not been reestablished.” The Bedouin tribes, however, did not join with the Iraqis in the fight, for their loyalty to Glubb Pasha, “Abu Hunaik” to the tribesmen, proved too strong. Qawukji, however, was an old enemy of the British: He had won the Iron Cross second class while fighting against them in the Turkish Army during WWI.

As Kingcol rested for two days at Rutbah before the next leg of their desert trek, Somerset de Chair, the intelligence officer of the expedition [he had held the same job against Rommel], received some disturbing news: “Seven unidentified aircraft had passed over Aley, near Beirut, heading for Iraq,” recalled de Chair. “Another 17 were reported to be refueling at Mezze. We knew they were Germans. Was this the advance guard of the 22d Airborne Division which I knew to be ready for action? Was it going to be sent through [Vichy French] Syria to assist the Iraqis, to whom lavish promises of German assistance were hourly made by Axis propaganda?” Worse yet, “one of our pilots on reconnaissance over Mosul [in northern Iraq’s oil fields] had been fired at by an Me 110.” Had the Wehnnacht already joined the battle on the side of 40,000 hostile Iraqi soldiers?

If this were so, things would be even worse for another British force than it would be for de Chair and Kingcol. Entrenched at the airport at Habbaniya on the Euphrates River west of Baghdad was a detachment of the RAF, with its planes and armored cars, 1,500 troops of Assyrian levies under British command, and a battalion of the British King’s Own Royal Regiment (KORR). They had already driven off an Iraqi attack with bombing runs at sanddune level, but the British force at Habbaniya would be in serious peril if the German 22nd Airborne entered the fight—their airfield would be a prime objective. Also endangered would be another British force, Indian troops, who were currently blockaded at the port of Basra.

The Urgency to Reach Baghdad Quickly Increases

More than ever Kingcol had to move fast to get to Baghdad before the Germans. De Chair recalled in his eyewitness account, The Golden Carpet, “the real advance now lay ahead of us. We were faced with the waterless stretch of desert, about 200 miles to the shores of Lake Habbaniya, which was fed from the Euphrates. But Ramadi at the north-west corner of the lake was held by one or possibly two brigades of the Iraqi army [two as it turned out] and was also surrounded by natural floods.” A long culvert on the road between Ramadi and Habbaniya had already been blown up by Iraqi engineers to block the relief of the besieged British by Kingcol. Now, the troops at Habbaniya were hurriedly building “an alternative trestle bridge” over the flood waters so Kingcol could come to their rescue.

But, as de Chair noted ominously, “If this trestle bridge were bombed by the Germans before we got across, we would not be able to relieve the Air Force garrison at all.” Accordingly, Kingcol lost no time in heading out into the desert in a race against the Germans. Still keeping to the ancient traditions of the British Army, the Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards, “the Household Cavalry, should lead off, with a truck load of Glubb’s Girls [as the British called the Arab Legion because of its long Bedouin robes] to guide them.” So Kingcol moved out, “gathering speed in clouds of dust on a mysterious course to the northwards, drawn on by the incalculable will-o’-the-wisp Bedouin who were their guides.”

Along tracks charted by the first British who explored the desert on the backs of camels, the men of Kingcol moved through the shimmering heat. De Chair plotted their course, although with the rough route laid out by those intrepid camel-riders as guides, he was not sure he was headed where he should. “I was going to Baghdad, but I prayed to my several gods at stated intervals to take me there by the right route.” Soon, though, de Chair’s fears of the column “streaming into Rutbah again over a wide front, as sunset closed a long and exhausting march,” were overtaken by a tragedy of a far graver kind. While ascending a rise in the ground, he looked back at Kingcol, snaking 20 or 30 miles out behind him like some long armored dragon, and then “suddenly I saw, with surprised eyes, two black tulips of smoke blossom far down the line, and, while the bomb bursts still hovered in the air, I saw the bright white-hot flash of anti-aircraft fire stream upwards across them. We had been discovered at last.”

The bombs from the unidentified planes—Iraqi, or German, the British could not be sure—had found their target. “A truck of the Essex Regiment had been hit, and some men were killed.” If the bombing raid were just the prelude to a major airplane attack, Kingcol would be desperately exposed on the flat desert. The column was forced to dig shelter trenches every time it halted for fear of an air raid striking from the cloudless desert sky, “all this in weather which made it impossible to touch metal where the thermometer reached 118 degrees. In the sun the metal seemed to have become incandescent. Men handled it with rags, grimed handkerchiefs, anything they could lay hold of.”

The Mission is Placed in Jeopardy

Suddenly, at this worst possible time, a series of disasters began to rain down on the troops. Brigadier Kingstone issued orders “to start the head of the column on a compass bearing that should bring it to the Wadi Abu Farouk [a “wadi” is a dried-out river bed], where it would turn west until it struck the flood race south of Lake Habbaniya at Mujara,” closer still to Baghdad. But when the column reached a point about 14 miles west of Ramadi, from where it would have been within striking distance of Baghdad, everything seemed to go wrong. First, perhaps feeling the effects of the incinerating heat, de Chair and the other leaders of Kingcol, like Major May of the Essex Regiment, were unsure of which path to follow by their compass, a critical factor when an error of only a few degrees might put the force miles off its route.

Then, finally deciding on a compass heading to set them on the best path to Wadi Abu Farouk, the column turned off into the desert—only to find that the dunes would not support the heavy trucks. Dispersed out of fear of an air raid, soon “the great supply monsters were everywhere floundering in soft sand,” noted de Chair. Those which had driven up the crisp ridges were now bedded down to the axles, while their crews labored in the desperate heat to dig them out.” At the same time, thirst began for the first time to become a serious problem for the already-suffering men of Kingcol.

The situation, especially the lack of water, became so alarming that Kingstone was forced to consider abandoning the entire mission. At a council of war, the brigadier told de Chair and the other officers that “we have enough supplies of water to stay here one more day. After that we go on or go back.” Then he addressed Glubb, “I shall want your dusky maidens to help us find an alternative route.” The next morning, three Arab Legion reconnaissance parties raced off in search of a better track to follow, and Somerset de Chair was sent off to find water, thirst becoming a more crucial problem with every hour the sun stood overhead.

As de Chair realized, he and his searchers might run into Bedouin, who would also be seeking water for themselves and their herds. Their interpreter, a man named Reading, suggested, just in case, that they should pretend to be Iraqi soldiers should any herdsmen discover them. Reading proved correct, and for good reason, because these Bedouin were enemies of the British. Encountering one, and asking if she had seen any British soldiers, an old woman answered no. “But,” she added fiercely, “I know what to do if I do,” and proceeded to produce an enormous knife. “After which,” de Chair concluded, “we thought it about time to return to our own encampment.” Fortunately, however, they succeeded in finding water at a place called Abu Jir. At the same time, Brigadier Kingstone, guided by the unerring Glubb, had found another line of march for the men, and had even reached Habbaniya unmolested by the rebels.

Fortune Turns Kingcol’s Way

Kingcol was fortunate to have received its new march directions when it did. Once again, death struck from the air. “Just as the tail of the column had been moving off from the camp, four black fighters had roared across the desert drilling the lorries [trucks] on the ground with bullets and cannon fire,” de Chair wrote. Had the planes, which de Chair was sure were German, struck earlier, “they would have found us the day before, immobilized in the soft sand,” and radioed bombers to fly in to massacre the trapped soldiers below.

Fortune, however, was now with the British, as they doggedly continued their march. The column reached Mujara, and from there went on to relieve the force holding Habbaniya, the Habforce, just like a relieving column in British India in the days of Gunga Din. Yet, as de Chair wrote, “the odds still seemed heavily against us. But we had been fortunate so far. And as the signpost on the aerodrome reminded us, Baghdad was now only fifty-five miles distant.”

During a council at Habbaniya, the fateful plans were made for the final advance on Baghdad. Now, however, it was made terribly clear that the British would be fighting not one enemy, but two, because the German Luftwaffeopenly entered the fight on the side of Rashid Ali’s Iraqis. Before Kingcol departed Habbaniya, “three light-green Heinkel bombers [came] flying over, the black cross clearly distinguishable through our binoculars.” No sooner had the German bombers dropped their deadly payload on the RAF hangers than four Messerschmitt fighters strafed the camp. How much longer would it be before the fallischirm-jagers [paratroopers] of the 22nd Airborne Division joined the combat too?

Before long, the first battle for the recapture of Baghdad erupted at Falluja. In a dawn attack, the Iraqis took the British by surprise in a determined assault with some small tanks. House-to-house fighting flared with the King’s Own Royal Regiment and the Christian Assyrians in the British force, mortal foes of the Muslim Iraqis. Kingstone himself rushed into Falluja to take over, for the Iraqis were gaining the upper hand, supported by townspeople sniping at the British from rooftops. Finally, with the Assyrians “tearing open the tanks with their hands,” and reinforcements called up from the column, the Iraqi attack melted away.

Falluja now became the base for the last push on Baghdad. Kingstone organized two columns to fight their way through any Iraqi—or German—opposition: the Northern Column comprised “most of the Household Cavalry, four 25-pounders, Glubb’s Desert Patrol, and the rest of the RAF armored cars;” the Southern Column comprised “one Squadron of the Household Cavalry, the two companies of the Essex Regiment, the independent anti-tank troop, three RAF armored cars and the Field Ambulance Section.” The main firepower rested in the 25-pounder guns. The Northern Column under Andrew Ferguson “was to be ferried across the Euphrates and reach Baghdad from the north after a wide detour around the Aqqa Quf floods. The Southern Column of 750 men under Joe Kingstone was to advance directly upon Baghdad down the road from Falluja.” The mighty 25-pounder artillery, ranked among the best field guns in the world, would serve as Kingcol’s battering ram.

The Challenge of Crossing Hammond’s Bund

The greatest obstacle for the British columns now was not the Iraqi Army, however, but a natural roadblock called Hammond’s Bund, a swampy gap in the vital causeway that was the main attack route into the capital. Immediately troopers were drafted to fill in the Bund. They worked around the clock, but as they filled in from the sides the middle channel only cut deeper.

Finally, working under de Chair, the Madras Sappers and Miners, the elite engineering corps of the Indian Army, devised another way. They used a large iron barge as a ferry. Recalled de Chair: “The sappers [laid] a pair of heavy ten-foot iron ramps from the end of the bund on to the end of the pontoon, in order to provide a pair of movable tracks for the vehicles to be run on to the ferry. A similar pair of steel ramps would be lifted on to the ferry from the bund when it reached the farther side.” The operation seemed simple enough except for one thing: The entire bridging operation and crossing had to be done under cover of night, with only the light of torches to guide the men. Once the sun came up, the Messerschmitts would be hunting their prey and the vehicles would have to scatter into the desert for safety.

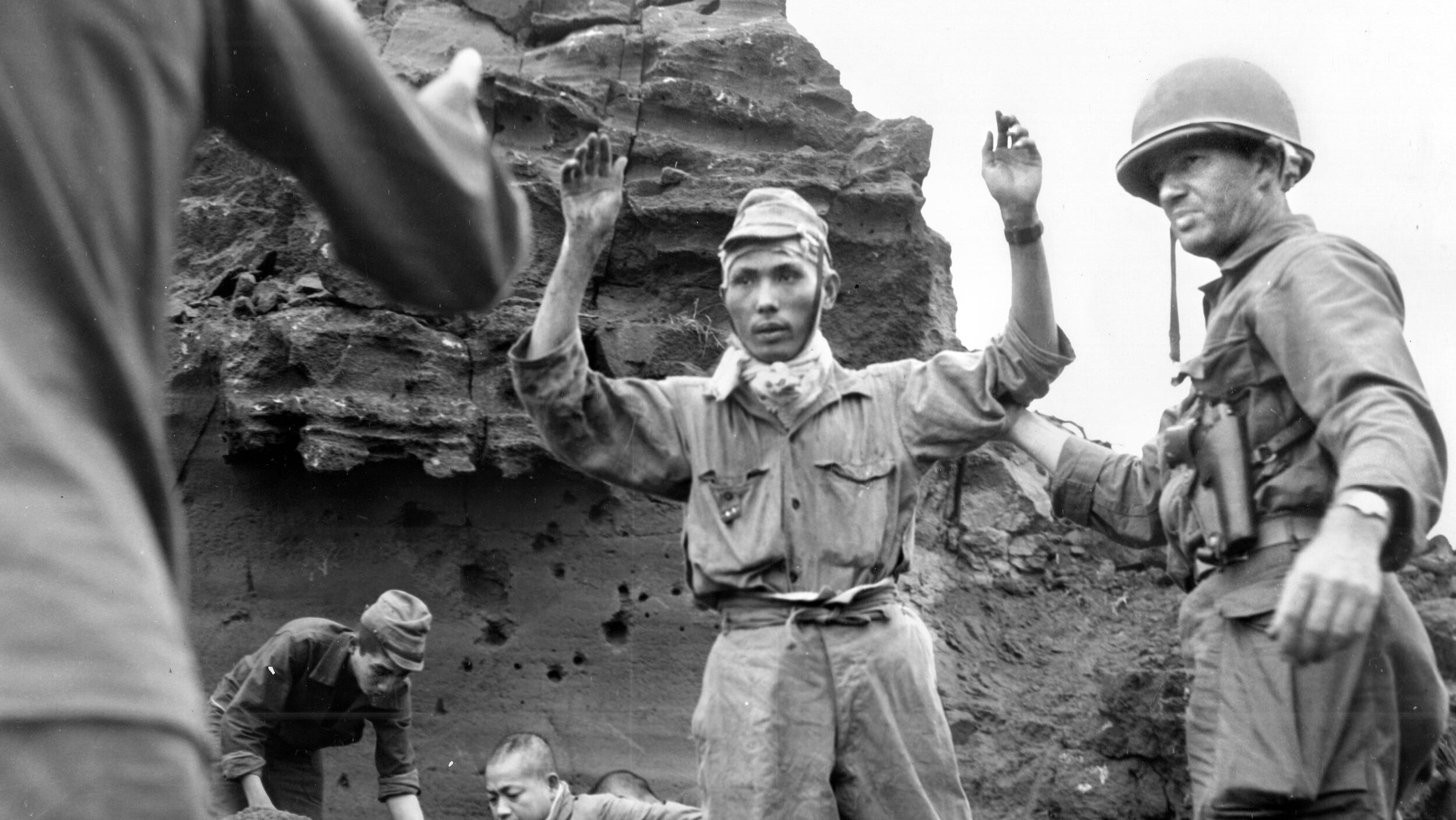

The bridging action went forward like clockwork and, by dawn, the caravan of the attacking force had passed over the Bund like the Hebrews crossing the Red Sea. Now it was time to confront the Iraqis, who had used the time Kingcol had spent spanning Hammond’s Bund to fortify the village of Khan Nuqta, 25 miles away. But faced with the British and the devastating power of the 25-pounders, the Iraqis surrendered. Somerset de Chair with the Southern Column arrived to see “our troopers were darting about among the network of ditches with bayonets on their rifles, stirring up Iraqi soldiers who quickly came out to surrender.”

De Chair’s Intelligence Coup

It was here, with the Iraqis in disarray, that de Chair was able to use his intelligence background. In their haste to surrender, the Iraqi communications officers had forgotten to cut the telephone link to Baghdad, and now de Chair and the British were able to listen in on all the plans the Iraqis made to defend the city. More than that, de Chair was able to play a deception game that threw the Iraqi defenders into a panic. Using the interpreter Reading, de Chair was able to convince the enemy that the British had a huge force of tanks, when there was not one with the entire Kingcol. De Chair reported that the excited defenders were completely taken in by the ruse. A patrol sent out to investigate from the 3rd Iraqi Division actually reported to Baghdad that “the British had at least fifty tanks, of which fifteen were already across the floods”!

Ultimately, an Iraqi technician discovered that the British were listening in on their conversations, and cut the line to Khan Nuqta, but not before, de Chair wrote, “the captured telephone had given me a complete X-ray of the forces ahead of us, besides enabling me to launch a wholly imaginary but very powerful tank attack of my own.” With the seizure of Khan Nuqta, “the first phase of the battle for Baghdad had been won.”

Stiffening Iraqi Resistance on the Way to Baghdad

But while de Chair’s column was moving on to Baghdad, Glubb’s force was being held up by stiffening Iraqi resistance at the holy city of Khadimain, where the Iraqis, all devout Muslims, had thrown up entrenchments. Moreover, Glubb’s column, the Northern Column, was deprived of the impact of bombarding the enemy at Khadimain for fear of alienating the overwhelmingly Muslim population of Iraq. Here, the battle for Baghdad was at the stage where things could have taken a decidedly bad turn for the British forces, for the Arab Legion were all Muslim, too.

But their loyalty to their regiment and to Glubb proved a stronger tie, and they fought the Iraqis for the city with a fierceness born of a pride in themselves and in their unit. As Glubb wrote later, “they were quite certain that, even if we beat the Iraqis, they were on the losing side and that the Germans would soon arrive. But in spite of this they not only fought on our side (the only Arabs who stood by us), but they were themselves continually pressing for more active operations, and making suggestions for new ways of attacking the enemy.”

While the Northern Column met determined opposition at the holy city, de Chair’s column was facing a hardened enemy as well. All of a sudden it seemed that the conquest of Baghdad was not going to be the easy exercise everybody in Kingcol had thought it would. Had the Iraqis received word that the Germans were on the way?

In Baghdad’s outskirts fighting centered around the Palace of Roses. “C” Squadron of the Household Cavalry dismounted from their trucks to begin the final rush on foot, across open ground commanded by enemy weapons. Recalled de Chair:“Machine-gun fire was opening up on us now, all along the belt of trees which screened the Palace of Roses, and the Blues [Royal Horse Guards] and the Life Guards were getting well down” into the dikes to shelter from the machine guns. Heavy artillery fire now joined in the bombardment of the Southern Column, and an even worse danger entered the picture: friendly fire, for the Southern Force was now within range of the 25-pounders of the Northern force.

But with the Northern Column still tied down before Khadimain, and the Indian Army units at Basra barely moving, the main assault on Baghdad rested on the shoulders of the men of the Southern Column. “So we were left alone, to seize victory if we could—and Baghdad was very near.”

An Unexpected Armistice

It began to seem that taking the city would be a costly operation because, as de Chair wrote, that night the “Iraqi guns on the Tigris seemed to be opening up into a furious barrage. It might presage a counter-attack in the dark.” Then, at “a quarter past midnight,” de Chair heard an officer giving a message to Kingstone: “Two delegates from the Iraq Army will appear on the Iron Bridge at two o’clock in the morning. Will we send two officers to meet them to discuss terms of the armistice?” Quickly, de Chair volunteered to go with fellow officer Ian Spence, and one from the Household Cavalry, Rupert Hardy, as well as an adventurous British diplomat, Gerald de Gaury.

Not knowing if they were heading into an ambush, de Chair and the other members of the truce party drove in the dark to an antitank ditch near the Iron Bridge leading into Baghdad. “There we were to erect our white flag. The Iraqi delegates were to show their headlights on the Iron Bridge and if we could see these, we were to respond by switching on our own.” As de Chair described their tense ride, “we were now moving forward, without escort, into No Man’s Land, where the fighting had been going on all afternoon.… There was no moon up and the darkness closing in on either side of the road brushed past the windows of our cars.”

When de Chair arrived at the antitank ditch for the rendezvous with the Iraqis, nobody was there. Spence and de Gaury moved out along the ditch, but they were stopped by barbed wire. Fearing trouble, de Chair went back to Kingstone for instructions. The brigadier told him “the Iraqi delegates are now expected at four o’clock.” De Chair and the others were to wait for daybreak and then return to Kingcol. De Chair returned with Kingstone’s orders and they waited alone for the Iraqis to come, not knowing if a machine gun might open up on them any minute from the darkness. Then, “suddenly from the right, following unexpectedly the course of the anti-tank ditch itself, came two cars rapidly, with headlights blazing. It was exactly four o’clock.” The Iraqis had finally come.

With Maj. Gen. George Clark, Kingstone’s senior commander, taking over the negotiations, work for an armistice began. Glubb Pasha came down from Khadimain to be a part of the victory for which he had fought so hard. De Chair was taken to Baghdad with Spence and de Gaury, guided by an Iraqi officer named Daghestani, to make contact with the Iraqi government and Ambassador Cornwallis. Rashid Ali, it was learned, had fled the country and the rebel’s military leader, Fawzi Qawukji, had taken refuge with the Vichy French across the border in Syria. The pro-British Regent Abdul Blah was on his way to take power. Terms for an armistice were rapidly concluded. All POWs were to be released on both sides, and any Germans or Italians in Iraq were to be interned. Most important, the Iraqis were to “facilitate in every way the task of British forces in the war against Germany and Italy.” Baghdad lay open to Kingcol. The Iraqi gateway to the oil fields of the Middle East had been barred forever to Rommel and his Afrika Korps.

After the agreement was signed, de Chair took the flag of truce and cut it in three pieces. “Taking from my map case a thick black lead pencil I wrote in bold writing on the corner of each third of the flag, ‘part of the flag of truce with which the emissaries from Baghdad were received at 0400 hours May 31st, 1941, to surrender the city and accept terms of armistice.’” De Chair gave one piece to Kingstone, another to Spence and kept the third for himself.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments