By Adam Griffith

Nineteen-year-old U.S. Army Specialist E5 James Griffith wasn’t particularly nervous when he boarded Seaboard World Airlines Flight 253 at McChord Air Base in Tacoma, Washington, on June 30, 1968. The plane was a sleek, new DC-8 Super 63 commercial airliner chartered by the Military Airlift Command to fly to Yokota Air Base near Tokyo, Japan, and then on to Cam

Ranh Bay, South Vietnam. Carrying 214 servicemen and 16 crew members, the plane made a brief stop at SeaTac Airport to refuel for the long flight ahead before it departed U.S. soil at 8:15 pm local time.

Griffith, a native of Holland, Michigan, was at the end of a 30-day leave and heading for his second tour of duty in Vietnam. He had enlisted in November 1966 and had been assigned to the 2/17 Field Artillery, 1st Cavalry, stationed at An Khe, South Vietnam. “I didn’t enlist because I wanted to go to Vietnam.” Griffith said. “I had just turned 18, had a really low draft number, and was told by a recruiter that if I went ahead and enlisted I would be stationed in Germany. But as soon as I completed my training, I received orders for Vietnam.

Flight 253’s Forced Landing

By June 1968, Griffith had completed his first tour and was given a choice of going to Fort Hood, Texas, or signing a six-month tour extension in Vietnam. “I got my orders to go to Texas and everyone in the room groaned when I told them,” he recalled. “I really didn’t want to go there anyway and everyone told me it was one of the worst places you could be sent, and I liked the idea of having a 30-day leave if I signed the extension, so I re-upped.”

As the plane headed for Japan and crossed the International Date Line, making it July 1 for those on board, Griffith noticed something strange. “I had flown this route when I did my first tour, and this time I noticed some islands that hadn’t been there before,” he noted. A Soviet MiG-17 fighter plane abruptly appeared on the left side of the aircraft. The men inside the airliner then realized the MiG was shooting bullets across the wing of their plane. “I’ll never forget the sight of the tracers being fired over our wing, and the feeling that we were about to be shot down,” Griffith said. “We could see the MiG pilot gesturing for us to land, and we were all wondering if we were going to make it.”

A second MiG had flown up behind the plane at the same moment. The pilot of the commercial plane immediately cooperated with the Soviet’s instructions, turning toward the nearby island of Inturup, part of the Kurile Islands, which had belonged to the Soviets since World War II. At the same time, on the ground a Japanese radar station noticed the plane had gone off course and warned the pilot but was told that the course could not be changed. The pilot later claimed that he had never actually heard the warning, as it was lost in static. “We must have been in Soviet airspace,” Griffith said. “We approached the runway from what was clearly the Soviet side.”

Negotiations Between the United States and the Soviet Union

By the time the plane landed, the pilot had quickly radioed what had happened. Soviet officials boarded within minutes and escorted the crew off. In addition, they asked for identification of everyone on board and ordered that the window shades be closed. “The manner of the men who boarded was blunt and their appearance was very formal,” Griffith remembered. “The guy I handed my ID to was wearing a red cape and was surrounded by armed guards.”

While the crew was being interrogated, Griffith and the other servicemen sat quietly in the plane. “We were all nervous, but no one panicked,” Griffith said. “The Soviets were very serious; but quite honestly, they seemed just as surprised to see us as we were to see them.” Later, the flight attendants were allowed to return to the plane, and the male crew members were kept in separate barracks. “As the hours dragged by, I eventually fell asleep,” Griffith said. “Later I found out that the Russians had brought over some soup while I slept, but no one woke me up.”

The following day, July 1 in the United States, a major non-proliferation treaty was signed in Washington, D.C., with similar signing ceremonies occurring in the Soviet Union and Great Britain. At the U.S. ceremony, President Lyndon Johnson was questioned about the American transport plane currently being held in Russia but refused to comment. Word had actually reached Secretary of State Dean Rusk the night before. He had already called a Soviet representative and instructed the American ambassador in Moscow to begin talks to free the hostages.

The incident had come at an inconvenient time for all involved. The United States was still negotiating for the release of the crew of the USS Pueblo, which had been seized off the coast of North Korea in January. In addition, neither the United States nor the Soviet Union wanted the fresh treaty to fall apart before the ink had even dried. For their part, the Soviets faced a double-edged sword. On one hand, they could hold the plane and strengthen their ties with China and North Vietnam, but also worsen relations with the United States at a time when both sides seemed willing to make significant concessions. On the other hand, they could release the plane and risk looking soft to their allies for allowing the soldiers aboard to go on to fight in Vietnam. After some initial communication on the issue, the U.S. Defense Department acknowledged vaguely that the plane “apparently strayed off course” by as much as 100 miles. They waited for the Soviet response.

“A Navigational Error”

Meanwhile, on the remote Russian island, the servicemen had spent an uncomfortable night in their airline seats. Griffith remembered: “After the initial way we were intercepted in the air, which was pretty frightening, none of us were really scared once we were on the ground. I didn’t worry that we would be physically harmed while under our present conditions, but I was worried that at any moment a bunch of trucks were going to pull up with armed men who would escort us off the plane and transport us to a Russian prison camp.”

The extended hours of camping in a parked aircraft were taking their toll; the lavatories in the plane had filled up, and the men were permitted to leave in large groups to use a facility nearby. “While I was outside, I saw that they only had a modest barracks, a small flight tower, and a few small buildings,” Griffith recalled. “It became clear to me that they didn’t really have the facilities to hold us for very long. Even the outhouse was just a hole in the ground.”

“We were really in the dark as to what was going on,” Griffith said. “No one was talking much, all we could do was sit and wait.” That night they were served rye bread, lard, and water. The flight attendants were taken off the plane again to sleep in a building that appeared to be used to manufacture clothing.

Back in Washington several hours later, the American ambassador made contact with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin, who said only that the matter was being looked into. Later that day, the ambassador handed Kosygin a note from Secretary Rusk that expressed regret to the Soviet Union over the violation of Soviet airspace, calling it “a navigational error.”

The Release of Flight 253

By July 3 in the Pacific, the pilot of the Seaboard World Airlines plane had signed a document stating that he had deliberately flown into Soviet airspace. Griffith remembered that everyone onboard the plane “was exhausted, and wanted to shower and shave.” The men had another meal of bread and water. Earlier that morning in Washington, word was sent by the Russians to the American ambassador that the plane would be released. The news was quickly announced at a press conference that morning. Again, President Johnson refused to comment.

The news reached the men on the plane that the Soviets were allowing them to leave. Griffith recalled, “I was glad to hear the news, but I didn’t feel we would be safe until we reached Japan.” The Soviets handed out cigarettes to everyone and allowed the plane to be refueled, and the servicemen all got off and pushed the aircraft into position so that it could take off again. As the plane taxied down the rough runway and finally lifted off, “I looked back from my seat at the window and could see the light metal runway rippling wildly behind us,” Griffith said. “We gained altitude and everyone cheered.”

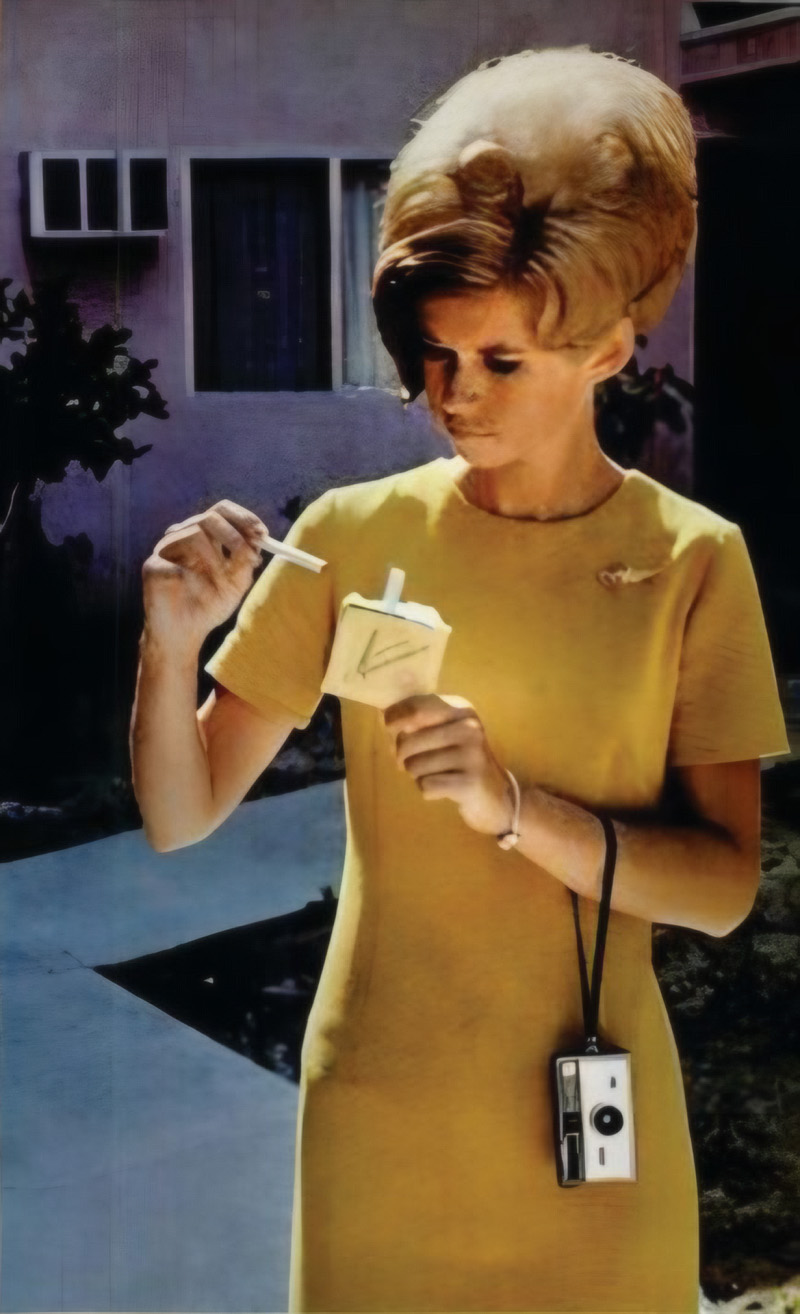

The flight to Japan was a short one—only about an hour, Griffith recalled. Once the plane was again safely on the ground, CIA officials boarded to debrief the men and asked if anyone had taken pictures during the incident. “The guy next to me had taken a bunch of photos while we were there, and pulled out his film,” Griffith noted. “I told him not to give it to them, but he said he was sure they would give it back. I don’t think he ever saw it again. Interestingly, one of the flight attendants had asked a couple of guys around me to take pictures with her camera when we were intercepted, as she couldn’t get a good look out the window. She didn’t say a word to the officials about her camera. Later, I saw her pictures in Life magazine.”

The crew was taken to a nearby Hilton to be interviewed by waiting reporters. During the interviews, the pilot adamantly claimed that he had done nothing wrong and had only agreed to sign the Russian document to gain the plane’s release, a position sternly maintained by Seaboard World Airlines. For Griffith, there was no press conference, just a few hours’ layover before he and the rest of the servicemen boarded the plane again. They flew to Cam Ranh Bay that night, where a large government staff waited to further debrief them.

Return to Vietnam

When Griffith finally returned to An Khe, he found that while he had been on leave a mortar round had landed on the roof of a building next to the one where he worked. “Shrapnel had flown everywhere and had gone through my building, completely shredding my typewriter,” he remembered. Later he discovered what a big story the plane incident had been when he learned that he had been featured in his hometown newspaper. For the next six months, Griffith was stationed at An Khe and at firebases in Mang Yang Pass and Happy Valley. As his second tour drew to a close at the end of 1968, he was offered another extension, but he opted to go home instead. “By this time things were becoming very dangerous,”Griffith said. “The Viet Cong had moved from hitting us with mortars to rockets, and the attacks were becoming more frequent. I was generally sick of the whole thing.”

In December 1968, the FAA released a report on the incident, which stated that the plane had been “operated carelessly so as to endanger lives and property of others by causing the flight to be performed with inadequate navigational equipment, permitting the aircraft to deviate from its course.” For this egregious error, which nearly set off an international diplomatic crisis, the airline was fined the grand total of $5,000.

Griffith was shocked in 1983 when he read that Korean Air Lines Flight 007 had been shot down over the Sea of Japan with 269 people on board, including Georgia Congressman Larry McDonald. The incident occurred, Griffith noted, “in a location very close to where our plane had been after it strayed into Soviet airspace. I thought about how easily that could have happened to our flight. What if our pilot hadn’t immediately complied with the hand signals from the pilot of the MiG?”

Looking back, Griffith believes that the crew and the State Department handled the situation well. So did the servicemen on the plane, he said, adding: “We were a well-controlled group. Everyone stayed calm, quietly talking to people seated next to them. We were all unsure what would happen to us, but no one panicked the entire time we were held in Russia. It was as if the whole situation was little more than an inconvenience. But I guess that was understandable. After all, we were headed to Vietnam.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments