By Christopher J. Chlon

Fregattenkapitän (Commander) Otto Kretschmer sank or damaged more Allied ships than any other U-boat commander during World War II. According to German records, he racked up 312,000 gross tons sent to the bottom or damaged.

Self-confident, well-trained, and with a ruthless quest for knowledge of the sea and ships, Kretschmer was a man who preferred ships to women. He carried himself with the bearing of a man who knew what he was doing and why he was doing it. He had other characteristics, too: a cruel contempt for weakness, an intolerance for anything that did not conform to his personal standards, a refusal to allow ordinary human failings to interfere with duty, and his pride, which was offset by a ready sense of humor and a willingness to listen to the problems of others providing they did not trespass on his privacy or lead to familiarity.

Born on May 1, 1912, in Prussian Silesia, he was the son of a schoolmaster who loved languages and science. Kretschmer shared his father’s loves and at age 17 went to Britain, France, Italy, and Austria to perfect his knowledge of both. At age 18, he joined the Reichsmarine as an officer candidate. After completing his officer training, he sailed for three months aboard the training ship Niobe, followed by a year aboard the light cruiser Emden.

The Treaty of Versailles had placed strict limits on Germany’s armed forces. Nevertheless, the Navy openly launched a reconstruction program. Under the command of Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, shipyards in Bremen, Hamburg, Wilhelmshaven, and Kiel built a new, modern fleet of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. However, Raeder was not satisfied. At a naval conference in Berlin, Raeder told Hitler, “The key to German power at sea lies below the surface. Give us submarines and we will have the teeth to attack.”

Six months later, Hitler gave him the “teeth.” He showed Raeder a telegram from Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop with the news that Britain had signed the Anglo-German Naval Treaty of 1935 giving Germany the right to build a surface fleet up to 35 percent of the size of Britain’s. Also included was a clause that allowed Germany to build a new submarine service of 45 percent of the Royal Navy’s and up to parity if a “situation arose which in their opinion made it necessary.” Hitler curtly told Raeder, “There are your teeth.”

Raeder quickly turned Germany’s diplomatic victory into action. He pulled World War I U-boat Ace Karl Dönitz from his duty on the cruiser Emden and put him in charge of rebuilding the U-boat arm. He made the anti-submarine training school in Kiel the center for teaching both defensive and offensive tactics.

Kretschmer’s career in the U-boat fleet began in 1936 as a trainee in Kiel. Along with the other trainees, he listened earnestly to Dönitz’s greeting. “The Navy represents the cream of the armed forces. The U-boat arm represents the cream of the Navy. A few of you will command your own submarines one day. But most of you will be sent back to the big ships you came from. The future of each of you depends on your individual efforts to meet the standards that I require of you.”

Two of Kretschmer’s fellow trainees, Gunther Prien and Otto Schepke, were delighted to have the chance to train for U-boat duty, getting them away from obscure duties on ships. Both would achieve notable success for the U-boat arm.

By the middle of 1938, the U-boat fleet had grown from two World War I training boats to 30 modern oceangoing attack craft. Trainee crews anxiously awaited the new U-boats under construction in Germany’s shipyards.

On the eve of the third meeting between Hitler and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in Munich in 1938, Dönitz called a secret meeting of his officers in his headquarters on the Baltic coast. More than 50 officers were there, including Prien, Schepke, and Kretschmer, all wearing lieutenant’s stripes.

Prien was given command of U-47, a 500-ton oceangoing vessel. Schepke had the smaller U-3, and Kretschmer took command of U-23, a small 250-ton attack boat. During his training Kretschmer acquired a reputation as the finest torpedo shot in the German Navy.

By September 1938, rumors of war filled the air. The new commanders anticipated their first assignments with nervous tension. They guessed that the meeting in Munich would shed some light on the talk of war. Dönitz did not keep them waiting and addressed the U-boat men. “Gentlemen, you will know by now that Führer has left Berlin to meet with the British Prime Minister at Munich,” said Dönitz. “I am assured by Admiral Raeder that he is determined to reach an agreement with England, but it is our duty to be prepared for the failure of any political settlement and the consequences which may result. You will therefore hold yourselves in readiness for hostilities as from now until further notice.

“Before leaving here you will be issued with sealed envelopes containing secret orders, and I must impress upon you that the seals are not to be broken until you receive signals from me indicating that hostilities have been declared. You will receive sailing orders from your flotilla leaders, and every operational submarine must be in battle stations within the next three days.

“Tomorrow a public announcement will be made that the German Navy is carrying out fleet exercises in the North Sea and the Baltic. This will serve to cover our real purpose. I hope—indeed I am confident—that the Munich conference will succeed in reaching a settlement with England. But should it fail, you will serve Germany in the forefront of the armed services. Good luck.”

In the following 12 hours, 25 submarines sailed into the North Sea from their bases in Kiel and Wilhelmshaven. They proceeded to set up patrols from the Shetland Islands in the north to the Atlantic coast of France in the south. Dönitz had thrown “a loop of steel” around the British Isles while Chamberlain and Hitler argued in Munich.

Two days later Kretschmer, in command of U-23, sailed into his first patrol. The boat had stores and provisions for 25 days at sea. Built to carry four torpedoes, it had only one in order to allow for magnetic mines to be launched. The boat patrolled the area 15 miles east of the Humber region of England. Submerged during the day to avoid detection, the boat surface at night to recharge its batteries. U-23 stayed on its battle stations for three days.

Gunter Prien and U-47 patrolled the waters off Scapa Flow, the main anchorage of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet. Concerned about the outcome of the meeting in Munich, Prien did not relish the idea of attacking the well-defended base.

Otto Schepke cruised far to the south and was not worried about possible orders. He amused his crew with sarcastic comments as his boat carried out dummy attacks on freighters and passenger ships in the English Channel.

Two days later, on the eve of their third day at sea, Dönitz signaled his commanders: “All units return to base with utmost dispatch. Exercises completed.”

Hitler had given Chamberlain his word that he had no further territorial ambitions. The two had achieved “peace for our time.”

Dönitz ordered his commanders to open their sealed orders, hold inquests on them, and to send him a composite report. Upon reading their orders, the commanders learned that they had been expected to lay mines in the entrances of all the rivers and harbors around England. They were to have attacked targets close to shore batteries inside what they regarded as a well-defended belt, running the risk of unknown antisubmarine devices. The commanders considered such operations suicidal.

By May 1939, the U-boat fleet numbered 56 boats with 40 operational. Fleet battle instructions called for all operational U-boats to be at battle patrols before war broke out. In August, Dönitz issued sealed orders to his commanders and banned personnel from communicating with friends or relatives until further notice. From August 17-27, the 40 operational U-boats slipped from their moorings and charted courses to their stations. Kretschmer eased U-23 into the waters off Wilhelmshaven with orders to place mines at the entrance of the Humber region. On Sunday, September 3, a message from Wilhelmshaven to all U-boats delivered the anticipated news in a coded message.

“1105/3/9/39 From Naval High Command stop To Commanders-in-chief and Commanders Afloat stop Great Britain and France have declared war on Germany stop Battle stations immediate in accordance with battle instructions for the Navy already promulgated.”

A second message followed from Dönitz that instructed commanders to open their sealed orders.

“1116/3/9/39 From Commander-in-Chief U-boats stop To Commanding Officers afloat stop Battle instructions for the U-boat arm of the Navy are now in force stop Troop ships and military ships carrying military equipment to be attacked in accordance with prize regulations of the Hague Convention stop Enemy convoys to be attacked without warning only on condition that all passenger liners carrying passengers are allowed to proceed in safety stop These vessels are immune from attack even in convoy stop.”

Kretschmer opened his orders, which instructed him to take U-23 to the Humber again and lay the mines that night. He estimated he would be ready by 10 pm. He brought U-23 to the surface about five miles from the entrance to the Humber. He was deciding the best way to enter the shipping channel when a new message arrived from Dönitz.

“From Commander-in-Chief U-boats stop To U-23 U-47 U-35 Return to base immediately stop Present operations canceled stop Acknowledge.”

Three days later Dönitz asked Kretschmer how long it would take to prepare U-23 for the open sea. The answer was 12 hours.

Dönitz said, “You are the first commander who seems to recognize that we are at war. You will sail at 8 amtomorrow. I want mines laid.”

The next morning U-23 sailed into the North Sea on the surface. During the voyage to the Humber, no ships were sighted. At dusk, submerged, Kretschmer eased the boat into the harbor at periscope depth, expecting to be discovered at any minute. The crew was tense as the mine laying operation took place without any problems. On the return trip, off the Firth of Forth U-23 sighted its first target. Kretschmer followed the ship and determined that its course would bring it within one mile of the U-boat.

“Torpedoes ready,” Kretschmer ordered. “Fire one.”

The crew was silent as it listened for the expected blast from the torpedo reaching the target, but there was no blast. Two more attempts were made, but neither struck the target ship. Kretschmer ordered the attack to end.

He and his officers then met to determine why the torpedoes failed, but the discussion ended without an explanation. Although he successfully laid the mines, he failed to sink the targeted ship, and he was angry that he had to report the mission was a failure.

During the return, U-23 stopped several ships in the Skagerak, a strait between the southeast coast of Norway, the southwest coast of Sweden, and the Jutland Peninsula of Denmark. Under prize regulations the belligerents could prevent the shipment of vital war materials to an enemy in neutral ships. Lists of cargoes had been published by France, Germany, and Britain. The Admiralty’s list of banned goods to Germany was lengthy and confusing to the German naval high command, which considered it irksome and a hindrance to their war effort.

One ship was Swedish, carrying timber. Kretschmer ordered a shot across the bow with the submarine’s 20mm gun. The ship stopped and sent up an international code signal: “I am stopped.” Kretschmer checked the list of cargoes for timber but it was not included. In frustration, Kretschmer allowed the ship to proceed.

Stopping neutral ships and checking cargoes became a sore subject as the war proceeded. Kretschmer stated his opinion in a message to Dönitz. “It seems strange that Germany should allow cargoes of stout timber to be moved freely to England, thereby making … pit props for mines that produce coal to make steel with, which in turn, is manufactured into weapons used to kill German troops.” U-23 returned to base, and the crew went on a short leave.

On October 1, Kretschmer received orders to patrol the western entrance to the Pentland Firth, which was the approach channel to the Orkney Islands and the British fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow.

During the three-day trip, U-23 was on the surface most of the time. Kretschmer studied his charts for Scapa Flow and worked up a plan to penetrate the anchorage. He planned to breach the defenses after dark, fire his torpedoes, and then retreat the same way he had entered.

On the third night of the patrol, while surfaced, the U-boat’s lookout spotted a darkened ship that was passing through the lights of a fleet of fishing boats. Kretschmer expected the fishing boats to suddenly become fast patrol boats, but that did not happen. He waited until the lights of the fishermen had faded. At 1,000 yards his gun crew fired tracer rounds across the bow of the darkened ship. Instead of slowing, the targeted ship increased its speed. He called out to his gun crew, “On the bridge this time.”

The second burst sent the ship’s crew scrambling to man lifeboats. Its radio operator sent out a distress signal in plain language. Kretschmer’s radio operator reported, “Target calling for assistance, sir. She is saying Glen Farg attacked by U-boat using gunfire.” Kretschmer allowed the crew to man their lifeboats before firing a torpedo. About 20 seconds passed before a blinding sheet of flame lit up the night from the middle of the coaster ship. After the smoke and spray had dispersed, the small ship sank in less than a minute.

The bridge lookout on U-23 watched the lifeboats as Kretschmer took the boat alongside and called out, “What ship and what were you carrying?”

The immediate answer was: “Glen Farg in ballast.”

“Right, head southeast and you will get the advantage of the current. Are any of you hurt?”

“No.”

“Sorry you are landed in this position. I am leaving now.”

“Thanks for coming over.”

While Kretschmer patrolled near the Pentland Firth, Dönitz developed a plan for attacking Scapa Flow. He assigned Prien and U-47 this daring mission. He needed a 500-ton boat that could remain submerged for 24 hours. Prien was briefed on the operation, and Kretschmer was ordered to take up a patrol in the North Sea away from the Orkney Islands.

At 1:16 amon October 14, 1939, Prien entered the harbor at Scapa Flow and fired a spread of three torpedoes toward the old battleship Royal Oak and the seaplane tender HMS Pegasus then turned around and sent a second spread of torpedoes that hit the Royal Oak on its starboard side and caused a magazine to blow up. The battleship rolled over and sank in 19 minutes, taking 834 crew members to the bottom.

Upon receiving the news of the Royal Oak sinking, there was jubilation across the U-boat arm. The Germans learned that the British had no secret weapon to defend their shores against U-boat attacks.

By year’s end, Kretschmer had successfully mined the Humber and Invergordon waters, sinking many Allied ships. At that point in the war, the mines had sunk more ships than the U-boats. Kretschmer acknowledged his successes with mines but was unhappy because he had not sunk more ships. During the first four months of the war, he accounted for only 6,000 tons. His mine-laying missions and patrols won him the Iron Cross 2nd Class, the Submarine War Insignia, and the Iron Cross 1st Class.

On his last trip before Christmas, he attacked a convoy off Farne Island, near the Firth of Forth. In less than one hour he sank the Deptford, 4,101 tons, and the Magnus, 1,339 tons. This patrol became known as “Kretschmer’s Shetland Sorties.”

After the attack on the Royal Oak, the British Home Fleet had disappeared from Scapa Flow, and Kretschmer was ordered to find it. He patrolled creeks and inlets in the islands, sometimes creeping in on the surface at night but more often sneaking around at periscope depth.

On January 12, 1940, Kretschmer inched U-23 into the entrance of Inganes Bay and to his surprise saw two patrol boats anchored on either side of the channel. Farther in the channel he spotted the outline of a tanker. Oil tankers ranked as the richest targets for U-boats.

He cruised back and forth across the entrance at periscope depth trying to find a way to enter the harbor past the patrol boats. Unable to do so, he surfaced U-23 and proceeded toward the tanker. After several minutes, he concluded that the patrol boat crews had bedded down for the night, but he determined that he could be caught in a crossfire between the boats if the crews were on duty.

The night sky was clear with a bright moon shining. As the range closed, Kretschmer ordered a torpedo launched. Its trail of bubbles was visible, and as it neared the tanker U-23 made a 180-degree turn and raced for open seas. As the boat distanced itself from the tanker, a huge red ball of fire shot skyward with a deafening roar, illuminating the gray low-slung ship for a few seconds. A second explosion sent a sheet of white flame across the bay with large chunks of the superstructure rising into the air. Kretschmer kept his field glasses on the patrol boats and saw crewmen scurrying around on their decks. After U-23 reached open waters, Kretschmer and his officers pored over their books showing the silhouette of merchant ships of all nations and decided that they had sunk the Danish motor tanker Danmark, 10,517 tons.

On another patrol in the Shetlands, they sighted what appeared to be a cruiser at anchor in Fell Sound. They crept into the bay and fired two torpedoes at the target. One struck with a flash and a roar, but Kretschmer’s navigator, Warrant Officer Petersen, shouted, “It’s not a cruiser; it’s a rock.” For a few moments, there was stunned silence in the conning tower. Suspecting a trap, they searched the bay but found it was empty.

Kretschmer was unhappy about wasting two torpedoes on a rock. Looking at his crew and their barely concealed grins, he sent a signal to U-boat command: “Rock torpedoed, but not sunk.”

The U-23 left the bay and charted a course for the Fair Isle Passage and the North Sea. On its way back to Kiel, two more ships were sunk, the freighter Polzella and the coaster Baltanglia. By the time they reached Kiel,U-23 had been at sea longer than any other boat in its flotilla.

After docking, Kretschmer reported to Dönitz on the depot ship there. Dönitz wanted a complete report of the action. He asked Kretschmer, “What about the torpedoing of the Nelson?”

“The Nelson?” Kretschmer asked in astonishment. “But I have not torpedoed the Nelson. I have never even seen the Nelson.”

Dönitz then telephoned the signal officer to bring in U-23’s file. When the officer arrived, Dönitz took the file and showed it to Kretschmer and then said triumphantly, “There, what does that say?”

Dumbfounded, Kretschmer read the report, which stated, “Nelson torpedoed but not sunk.” He thought for a moment and then shook his head in amusement as he realized a mistake had been made. The German word for rock is Felson, and in the transmission report it had been entered as Nelson.

Dönitz sat down and said: “So you attacked a rock.” He began to laugh.

“Oh Kretschmer, if you could know what I am thinking, I do not think either one of us would be laughing. Can you see the look on Goebbels’ [Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels] face when he hears this.”

Dönitz put in a call to Berlin and then turned to Kretschmer.

“All right, I will get tonight’s announcement stopped. They were going to say, ‘Where is Nelson, Churchill…?’ I do not need much imagination to guess what reply would come from the Prime Minister.”

On February 9, 1940, U-23 sailed from Kiel on its eighth patrol. Soon after its departure, the lookout shouted, “Torpedoes to starboard.” Kretschmer ordered control to steer hard to starboard and watched three lines of bubbles racing toward him. He ordered the ship to dive, and it leveled out at 50 feet. He and the crew listened to the propellers of the torpedoes, bracing themselves for impact, but the torpedoes missed. Kretschmer determined a British submarine had fired at them. After the torpedoes had passed, U-23 surfaced and headed toward its rendezvous point.

A convoy lay ahead, and two destroyers were spotted. Kretschmer sank one of them. He then steered a course parallel to the convoy. While on this course a lone merchant ship appeared on the horizon. He attacked with two torpedoes that struck the ship, causing a gigantic roar. After checking the books, he told his men that they had sunk the freighter Tiberton, 5,225 tons.

Three days later off the east coast of the Orkneys, Kretschmer sank another freighter, the Loch Maddy at 4,996 tons. At this point, he had used all his torpedoes and steamed toward Kiel. After his arrival, Dönitz ordered him to take U-23 back to the Orkneys, but it turned out to be a fruitless patrol. This patrol lasted nine days, and Dönitz ordered him to return to Kiel on the last day.

This patrol was Kretschmer’s last as commander of U-23. He had taken it on nine patrols, spent 96 days at sea, and sunk eight merchant ships and one destroyer, racking up 30,000 tons.

In late April Kretschmer received an order from Dönitz informing him that he would be taking command of U-99, a new boat. It was a 500-ton oceangoing boat with a complement of 44 men and 12 torpedoes. Compared to the U-23, the U-99 was luxurious. After loading stores, the captain took a skeleton crew for a trial run in the Baltic. They dived, fired torpedoes, and the gunnery crew completed its exercises without any problems. Kretschmer put his new boat through its paces until June 17, when he set out for the Atlantic.

During this patrol Dönitz signaled that the battlecruiser Scharnhorst was sailing along the coast of Norway and German aircraft would be making antisubmarine patrols in a 30-mile radius around the ship. Kretschmer was to keep outside that range, otherwise U-99 might be attacked. The next day the lookout sighted a British submarine, which appeared to be unaware of U-99. Kretschmer changed course to give the enemy sub a wide berth, but the British sub spotted U-99 and dived.

Kretschmer expected an attack and ordered the boat to full speed, taking it out of range of the sub, but his navigator informed him that they were within range of the Scharnhorst. At the same time, the lookout spotted an aircraft approaching. Kretschmer sounded the alarm to dive, but it was too late to escape. The plane attacked, dropping a bomb that exploded on impact with the sea. There were no leaks, but the periscope was jammed and its lens broken along with the compasses. Kretschmer cursed the fact that he had been attacked by German planes. With such damage, he decided to return to base for repairs, which took three days.

On July 5, Kretschmer began a new patrol, sinking Allied ships almost immediately. Seeing Convoy HX52, Kretschmer took aim at a Canadian steamer, the Magog, and sank it. The crew of the Magog had manned their lifeboats, ready to jump overboard because of the deck gun on U-99. Kretschmer reassured them he was not going to shoot them, and after conversing with the Canadian officer tossed him a bottle of brandy with instructions on how to reach land safely.

Two days later, Kretschmer sank the British steamer Sea Glory with two torpedoes at about 1 am.At about 11 pm, the Swedish steamer Bissen went down after being hit with a torpedo.

This patrol saw the sinking of ships from Canada, England, Greece, and Sweden. An Estonian ship, the Merisaar, became Kretschmer’s first prize. Attempts to sink it failed, and as a result Kretschmer ordered the crew, which had taken to lifeboats, to reboard the ship and set a course for Bordeaux. Total tonnage amounted to 22,719, for about two weeks work. It was a sign of things to come.

Kretschmer took his new U-boat and crew to Lorient for a rest, arriving on July 21. He felt close to his crew because none of them had panicked while enduring depth-charge attacks from British ships. He took them all out to a restaurant for a fine dinner. Afterward, the enlisted men explored Lorient and proceeded to get drunk. Dismayed at their behavior, Kretschmer delivered a stern sermon to them, demanding the same discipline on shore leave as they showed while on patrol. His crew relaxed in Lorient, but Kretschmer spent time welcoming other U-boats whose missions had been completed. On July 24, Dönitz ordered him to make another patrol.

At 4 AM on July 28, the weather report indicated calm seas and long swells with a light breeze. An hour later a British motor merchant was spotted. Kretschmer closed to about 11/2 miles. While on the surface, he fired his first torpedo, which hit the ship’s stern but did not sink it. As its crew manned the lifeboats, a gun crew on the stern aimed at U-99. Alarmed, Kretschmer took the U-boat down and fired two more torpedoes. After languishing for about two hours, the Auckland Star vanished from sight. This ship turned out to be the first of seven attacked by Kretschmer on U-99. Four were sunk and three damaged.

Convoy OB191 came into view on July 31. Kretschmer maneuvered his U-boat until it was ahead of the ships, violating the principles he had been taught. U-boat commanders had been instructed not to wait but to attack a convoy as soon as they could fix a target at periscope depth outside the ring of escort ships and to fire a spread of torpedoes. Kretschmer knew this, but instead his strategy was to get ahead of the convoy to be in position for a surface attack. He wanted to prove that he could attack by night on the surface and carry out his motto, “One torpedo, one ship.” He considered spreads of torpedoes to be wasteful. He took a calculated risk and became the first U-boat commander to attack convoys at night while on the surface. He returned to Lorient on August 2 having sunk or damaged 57,890 tons of Allied shipping.

A military band and a welcoming group of staff personnel greeted Kretschmer and his crew on August 7 as he departed the escort ship on the pier at Lorient. Seven victory pennants waved in the breeze, one for each ship sunk or attacked.

Before going ashore, Kretschmer explained his decision not to attack the convoy during the day while submerged. His report noted that rough weather made it necessary to maintain contact with the target ship. Dönitz did not fault him for not carrying out the standard procedure to make an attack.

The following day Dönitz telephoned Kretschmer and invited him to a meeting that afternoon. Kretschmer left for Paris and soon learned that he was to receive the Knights Cross “for the greatest number of ships sunk by a commander in one voyage” and “continuous determination and skill” in the face of the enemy. He was also told that Admiral Raeder would personally present the medal the next day.

All of the naval crews in harbor at the time lined up for inspection by the Navy’s commander in chief, with the men of U-99 in the place of honor in the center of the parade ground. Raeder congratulated Kretschmer and his crew for their accomplishments and handed him a flat box containing the Knight’s Cross and sash. After Raeder left, Kretschmer and his crew celebrated on the deck of U-99 with beer for everyone.

On August 26, Kretschmer received his orders for Operation Sea Lion, the planned amphibious invasion of England. The task was to prevent any British ship from entering the English Channel from the west.

Days later, Dönitz invited Kretschmer to the Hotel Terminus, where he was introduced to an Italian submarine officer, Commander Longobardo, who commanded a submarine base in Bordeaux. The Italian Navy had sent him to Dönitz to learn German attack methods.

Dönitz said, “Kretschmer, I want you to take Commander Longobardo with you on your next trip. You should be ready to sail within 24 hours. I think you had better see that his gear gets aboard U-99 today.”

Kretschmer was not happy about this guest, even though it was customary to have another German officer on board to study operational methods before getting his own command. Dealing with an Italian commander who could not speak German was a different matter. He tried to speak to his guest in German, but Longobardo replied in Italian. Kretschmer then spoke to him in English, and the Italian replied in English.

Once underway, U-99 sailed across the Bay of Biscay into the Atlantic and the area called “U-boat Alley” by the Royal Navy. While standing on the conning tower with his guest, Kretschmer heard his lookout shout, “Aircraft on starboard beam, sir, height about 40 degrees!” Kretschmer ordered the boat to dive, but it went well past periscope depth. To reach the depth he wanted, he ordered compressed air to be blown into the forward ballast tanks. His Italian guest watched intently, and Kretschmer wondered about the impression he made with his guest. He said, “Sorry about that. These things happen at times.” The Italian replied, “That’s all right. I knew you would right her easily.”

On September 8, Kretschmer was following an outbound convoy when U-99 was spotted by a destroyer. He gave the order to dive and spent that night and the following day tailing the convoy. He surfaced but was immediately seen by another destroyer. Once again, U-99 dived, depth charges falling around it. He took the boat down to 300 feet to wait out the attack. Thirty explosions were counted before they stopped. After the echoes of the destroyer had faded, U-99 surfaced only to be attacked by another destroyer. Down it went again, and a round of depth charges knocked the boat on its side, sending most of the control room crew rolling on the deck. Then the destroyer ended the attack and sailed off.

Back on the surface, Kretschmer scanned the horizon for a convoy. One large freighter was spotted, and two torpedoes were fired. They leaped from the water and went off course. Kretschmer dropped back to the stern of the convoy but was again spotted by a destroyer and had to dive to evade the attacker.

His luck changed when he sank the British steamer Albionic on September 11. It was the first sinking on this patrol. More followed four days later as the Canadian steamer Kenordoc, the Norwegian Lotos, and the British Crown Arum were sunk between August 15-17.

In a matter of about 90 minutes on September 21, Kretschmer sank three ships that were part of Convoy HX72. All were British ships, the Invershannon, Baron Blythswood, and Elmbank. As he watched his victims burn, a lifeboat occupied by one man in his underwear was spotted. Kretschmer took him on board and sent him below, where he was given dry clothes and food. Now Kretschmer had two guests on board. He decided that he could not take his prisoner back to Lorient, so he eased U-99 close to the lifeboats from the Invershannon and handed over the prisoner. Out of torpedoes, Kretschmer headed for Lorient.

After disembarking, Kretschmer and his men dined at a local restaurant, Beau Sejour. They celebrated with many toasts, and afterward the men were informed that a rest camp had been provided for them at Quiberon. Kretschmer took a train to Paris to meet with Dönitz.

Meanwhile, Dönitz learned that Britain had undertaken additional measures to combat the U-boats. A new director of antisubmarine war, former destroyer commander Captain George Creasy, had been appointed. His job was to overhaul this office and to advise the Admiralty on what action should be taken to stem the tide of losses to U-boats. Creasy considered himself the direct opposite of Karl Dönitz. The moment of his appointment marked the official beginning of the Battle of the Atlantic.

On October 13, 1940, U-99 sailed on her fourth Atlantic patrol, clearing the harbor at Lorient at 1:30 amthe next day. Less than an hour later, Kretschmer received a signal that Lorient harbor was closed because of mines that had been laid by the British. Two days later they received a signal from U-93 that a large convoy was outbound from England. It was designated SC7.

Six other U-boats along with U-99 were ordered to form a “stripe” across what was considered the path of the convoy. They were U-93, U-100, U-28, U-123, U-101, and U-46. Two additional U-boats later joined the chase. At the same time in London, signals received from escort ships reported that the convoy was being shadowed. Just after dark U-99 was spotted, but Kretschmer eluded the escort.

At about 10 pm, seven U-boats began firing toward the convoy from outside the escort screen. Kretschmer trimmed U-99 up for maximum speed and maneuverability and raced inside the escort screen. He passed between two destroyers, one on the bow and one on the beam of the convoy, with about a mile to spare on either side. Within three minutes he was through and approaching the outer column of the convoy. In less than two hours, Kretschmer torpedoed and sank three ships, Empire Miniver and Fiscus from Britain and Niritos from Greece.

The following day, October 19, Kretschmer sank three more ships in one hour. These victims were Empire Brigade from Britain, the Greek steamer Thalia, and the Norwegian Snejfeld. Later in the day, U-99 damaged the British ship Clintonia but did not sink her. She was finished off by U-123.

Kretschmer returned to base on October 22 and received a hero’s welcome for his successes against Convoy SC7, which lost 17 ships in two nights. Kretschmer had accounted for half of them. His efforts did not go unnoticed. In his battle report, Dönitz noted, “Excellent led attack on convoy which has been rewarded with corresponding success. Signed Dönitz, Commander-in-Chief, U-boat Command.”

After a leave of three weeks, U-99 departed Lorient on a short but productive patrol. In a matter of three days, four British ships went down, including two armed merchant cruisers, the HMS Laurentic and the HMS Patroclus. After returning, a message was handed to Kretschmer:

“TO COMMANDING OFFICER U-99: WELL DONE STOP COMMANDING OFFICER OTTO KRETSCHMER AWARDED OAK LEAVES TO KNIGHTS CROSS STOP WARRANT OFFICER PETERSEN AWARDED KNIGHTS CROSS STOP COMMANDER KRETSCHMER WILL RECEIVE DECORATION FROM FUEHRER STOP COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF U-BOATS.”

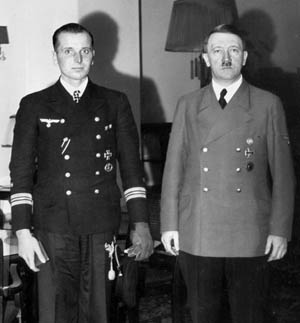

On November 12, Kretschmer was the only passenger in a Siebel five-seater plane that took him to Berlin. Admiral Raeder greeted him, and the two discussed the war effort. At 11:30 am, Raeder’s car took Kretschmer to the Reich Chancellery where he was greeted by Captain von Puttkamer, who instructed him on the protocol for receiving the award. At noon, the large doors opened and Hitler walked in along with an adjutant. Kretschmer was presented to Hitler, who formally awarded him the Oak Leaves. Afterward, they sat down and Hitler spoke:

“It is good that the enemy started this war so early, as it would have been a much harder task if they had waited to build up their strength. So, for our naval warfare, we have secured the ports of the Bay of Biscay. I am most happy about that. At the beginning of the campaign I was determined to get the French Channel ports for our submarine warfare.”

Hitler asked Kretschmer how the war was going, and the reply was that more U-boats were needed as soon as possible. Hitler nodded and thanked him for his comments. “Thank you, Commander. You have been very frank, and I will do what I can for you and your colleagues. You will be lunching here with me.”

After lunch, Hitler stood up and left the room. Captain von Puttkamer and another adjutant joined Kretschmer in another room for coffee, brandy, and cigars. Later that evening, the staff car took Kretschmer to the state opera and the box used only by Hitler and important guests. Kretschmer sat alone in the flower-filled box.

He was flown back to Lorient, where he took U-99 on patrol on November 27. In 15 days Kretschmer sank three British ships and one from the Netherlands. He returned to Lorient on December 12. He and his crew took leave and returned in February 1941. U-99 embarked on its eighth and final patrol on February 22.

After searching for two weeks without sinking a single ship, U-99’s luck changed on March 7 when two British and one Canadian ship were added to its impressive record. Nine days later, Kretschmer attacked convoy HX112, sinking five and damaging another. The next day U-99 was attacked by the British destroyer HMS Walker using depth charges and inflicting major damage. Kretschmer scuttled U-99 at 3:43 AM on March 17, and he and his men were taken prisoner aboard the Walker.

For Kretschmer’s colleagues Prien and Schepke, March 1941 was fatal. Prien and U-47 went down with all hands on March 8. Schepke died on the same day that Kretschmer scuttled U-99. In less than two weeks, three of Germany’s ace U-boat commanders disappeared from the high seas.

HMS Walker docked at Liverpool, the British operational center for the Battle of the Atlantic. After docking, the captives were forced to march through the streets. They were greeted with angry demonstrations by hundreds of women who had lost loved ones to U-boats. From Liverpool, they were sent to London for interrogation and ultimately to the prisoner of war camp at Grizedale Hall. They remained there until October 1942, when they were transported to a Canadian POW camp, Camp 30, in southern Ontario.

Bowmanville, Ontario, sits in southern Ontario east of Toronto and Oshawa on Highway 2. The town was an incorporated community from 1858 to 1973. In 1941, there was a school for delinquent boys on the former farmland of Mr. John H.H. Jury. He donated his land to the government for the school in 1927, and it was in use until April 1941, when the government gave the school notice to find a new home because the facility was going to be turned into a prison camp. Work was completed in October 1941, and it was designated as Camp 30.

This POW camp had things that others lacked, including an indoor pool, athletic complex, and soccer and football fields. The prisoners played soccer, Canadian football, and hockey in the winter. They built a tennis court and a mini zoo. They could receive and send mail to and from family members. They received new uniforms from Germany and got their regular pay with which they could buy such items as cigarettes, cigars, tobacco, pipes, and razor blades. Medical and dental services were provided by German doctors. An orchestra and theater group put on various Shakespeare plays.

Since the camp was located on a former farm, the prisoners’ meals were much better than those served in other camps. Breakfasts included coffee, jam, and butter. Lunch often featured roast beef, potatoes and gravy, and carrots. For dinner, macaroni, ham, soup, cheese, bacon, and tea were on the menu.

Even though the living conditions at the camp were quite good, it was still a prison camp, one that held high-ranking officers of the Afrika Korps, Luftwaffe, and the Kriegsmarine. One of the most prominent prisoners was Otto Kretschmer, the most successful ace of the German U-boat arm during World War II. From October 1939 until his capture in March 1941, Kretschmer sank about 312,000 metric tons of Allied shipping. He was so successful that he was given the nickname “Atlantic Wolf.”

After arriving at the camp, Kretschmer began planning his escape.

He developed a plan with three other U-boat officers, Hans Ey of U-433, Horst Elfe of U-93, and Joachim von Knebel-Doberitz. Before proceeding Kretschmer needed to contact Dönitz for permission. This was accomplished by sending a coded letter to the spouse of Knebel-Doberitz, who happened to be Doenitz’s secretary. The letter relayed the intention to escape, proposed that the escapees be picked up by a U-boat, and even proposed a rendezvous location. Dönitz approved the escape attempt and preparations began.

Kretschmer intended to burrow a tunnel under the camp. To throw off the guards, three tunnels were dug. More than 150 prisoners took part in the digging. The intended escape route would extend beyond the camp and the barbed wire that surrounded it. At the same time, prisoners prepared false identification papers, civilian clothes, and dummies to be used as substitutes for the escapees.

While the work was being carried out, coded letters with progress reports and updates were sent to Germany. In August 1943, through a coded letter and radio transmission, the date was set for the breakout. In yet another letter from Dönitz, Kretschmer was advised that U-536, commanded by Lieutenant Schauenburg, would surface every night for two weeks beginning on September 23, 1943. Kretschmer and his men would have 14 days after their escape to make it to the rendezvous location at Pointe Maissonette in Chaleur Bay.

The Germans did not know that the escape plans had been discovered by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Canadian Military Intelligence. Maps of eastern Canada were discovered in the Germans’ mail, and one was for a rescue operation in Chaleur Bay. To learn more about the escape, the RCMP used a microphone to discover the presence of a tunnel and the sounds of digging. This information was not shared with the prisoners. The intent was to allow the Germans to keep digging and apprehend them once they emerged from the tunnel.

Two incidents changed the Germans’ efforts, code named Operation Kiebitz. Digging the tunnel meant having to hide the dirt, and this was accomplished by putting it above the ceiling in the building where they were housed. One week before the attempted escape, the ceiling caved in, causing a racket that alerted the guards, who began to search for the source of the dirt. Due to this unexpected problem, Kretschmer decided to take action that night. However, another surprise occurred when a prisoner digging close to the camp’s fence to fill his flower boxes with dirt felt the ground beneath him cave in, uncovering the third tunnel. The escapees were arrested and put under close watch.

Kretschmer remained a prisoner of war for nearly seven years and finally returned to Germany in 1947. In 1955, he became an officer of the Bundesmarine, the navy of the Federal Republic of Germany. He retired in 1970 with the rank of flotilla admiral after also serving in several positions with NATO. Kretschmer died following an accident while on vacation in Bavaria in 1998. He was 86 years old. His body was cremated and his ashes scattered at sea.

Christopher Chlon is a retired purchasing professional whose work has appeared in numerous historical and trade magazines. He is a graduate of Loyola University in New Orleans and resides in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments