By Mike Phifer

Marshal Auguste Marmont watched intently as the left wing of his French army maneuvered against the Anglo-Portuguese army during the Battle of Salamanca at mid-afternoon on July 22, 1812. He noted that the 5th Division of General Antoine Louis Popon de Maucune was in danger of being destroyed as it advanced toward the village of Los Arapiles. The 5th Division should have been closely supported by General Jean Guillaume Barthelemy Thomieres’ 7th Division, but that division had marched too far west. If Thomieres’ division continued on its present course it not only would fail to support Maucune’s division but also would lose contact with the main army.

Realizing that Arthur Wellesley, Earl of Wellington, the commander of the Allied army, would in all likelihood exploit the confusion that had engulfed the lead units of the French left wing, Marmont decided to ride down into the valley to take command of the left wing himself. He spurred his horse and picked his way through the rubble on the west slope of the Greater Arapile, a barren ridge where he had enjoyed a sweeping view of the battlefield.

Marmont intended to halt Thomieres’ march and redirect his troops. But as the French commander made his way off the ridge, a British shell exploded next to his horse, causing serious wounds to Marmont’s arm and ribs. While his aides carried him from the field, dispatch riders galloped off to inform 2nd Division commander General Bertrand Clausel that he was now in command of Marmont’s Army of Portugal. The battle was heating up at the time, and the French army was without a commander for nearly an hour. During that time, the situation on the French left flank deteriorated significantly.

The Earl of Wellington experienced a real sense of accomplishment in the spring of 1812, having driven the French from Portugal. Between January and April he had pried the French from the fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz. Flush with these victories, the British commander was ready to push deeper into Spain. He could advance into Andalusia and engage Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult’s army in an attempt to relieve the beleaguered Anglo-Portuguese garrison at Cadiz, or he could pursue Marshal Auguste Marmont’s army in Castile. He chose the latter.

After the fall of Badajoz, Wellington improved his supply lines from Lisbon and Oporto. This was a critical step before the Anglo-Portuguese army advanced into Castile. While these efforts were underway, Wellington ordered a raid to cut the link between Marmont’s army and Soult’s army. On May 7 Lt. Gen. Rowland Hill was ordered to move out with a force of about 10,000 British and Portuguese troops, along with a battery of heavy guns, and destroy the pontoon bridge across the wide Tagus River that connected the two French armies.

The raid was a total success, with Hill’s force storming the forts and defensive works that protected the bridge and driving off the French defenders on May 19. The pontoon bridge and fortifications were soon destroyed, easing Wellington’s concern about Soult having direct communication with Marmont.

Leaving Hill with 18,000 troops near Badajoz on the Spanish frontier to protect the southern route between the two countries and his southern flank, Wellington marched east on June 13. The primarily Anglo-Portuguese army included several thousand Spanish troops.

Eight hundred French troops garrisoned three forts in the southwest corner of Salamanca. The forts were situated on high ground overlooking the old Roman bridge across the Tormes River. Fort San Vincente, which had 30 guns, was the most robust of the three forts. French engineers had destroyed buildings to make sure the only approach to the stone fort was across open ground. The two smaller forts, Le Merced and San Gaetano, were separated from San Vincente by a steep ravine.

Wellington had been informed by his Spanish agents that the forts were weak, but he quickly learned otherwise. To batter and breach the stone forts, the British had only four 18-pounders, although six heavy guns were making their way to Salamanca.

Wellington assigned Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton’s 6th Division the job of capturing the three forts. The Allied commander accompanied the 14th Light Dragoon when it entered Salamanca to the shouts of the townspeople. Wellington established his headquarters in the town, and the 6th Division invested the forts that night. When the French opened fire with artillery and small arms on the Allied troops, several hundred marksmen from the Light Brigade of the King’s German Legion spread out among the ruins of the town. They opened up with a brisk fire that kept the French pinned down. This enabled the British artillerists to get their guns into action against the forts.

As for the bulk of the Allied army, it bypassed the town on June 19 and took up position on the heights at San Cristobal three miles to the north. Marmont had difficulty keeping his troops supplied, and therefore he dispersed his units until he knew where Wellington was going to strike. On June 19, the French commander gathered five of his eight divisions and set out to relieve the garrisons of the three forts in Salamanca.

General Jean Pierre François Bonet’s 8th Division was not scheduled to arrive until early July for it had to march from Asturias to the north. Marmont also sent a request for help to General Marie-François Auguste de Caffarelli in command of the Army of the North. Caffarelli had previously promised to send 8,000 infantry, a brigade of light cavalry, and 22 guns if Wellington attacked Marmont. Marmont also sent a message to Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother who had been installed as the king of Spain, requesting troops.

Watching Marmont’s 25,000 troops arrive, Wellington hoped the French would attack his numerically superior force. Wellington’s army held a strong position from San Cristobal to Cabrerizos with cavalry covering his flanks. British guns emplaced on the heights shelled the French as they advanced in three columns, approaching to within 800 yards of Wellington’s lines. The French guns replied in all likelihood to let the beleaguered garrisons in Salamanca know help was on the way.

At dusk a French regiment attacked the British advance post at the village of Morisco, located at the foot of the heights. The village was held by the 68th Light Infantry of the 7th Division which beat off three French attacks. After dark Wellington recalled the 68th and abandoned Morisco. Wellington hoped that Marmont would attack him in the morning, but Marmont did not take the bait.

Knowing he was outnumbered, Marmont did little the next day, even though two more divisions and a brigade of dragoons arrived that afternoon. Even with the reinforcements, Marmont was in a bad position, with no flank protection and only open ground behind him that offered no protection in case of retreat. The council of war was divided nearly down the middle. Marmont decided that it would be best to err on the side of caution, and therefore he refrained from launching an attack.

By June 22 it was clear to Wellington that the French were not going to attack. There was some skirmishing in the morning before the French withdrew six miles to Aldea Rubia that night. For the next four days Marmont maneuvered his army east of Salamanca. He did send part of his army across the Tormes in an attempt to get Wellington to divide his force, but the savvy Allied commander easily countered the French moves.

Word arrived on June 26 from Caffarelli that he would not be sending reinforcements to Marmont due to guerrilla activity and threatening moves by the Royal Navy in his area of responsibility. News came the next day that the forts in Salamanca had fallen. The garrisons had held out for 10 days. Clinton’s 6th Division lost 120 men in failed assaults against San Gaetano. A shortage of ammunition had slowed Clinton’s efforts, but fresh ammunition arrived to tip the balance in favor of the besiegers. Allied guns ultimately forced the fall of all three forts.

With the fall of the forts and with no reinforcements from Caffarelli on the way, Marmont withdrew northeast toward Valladolid on the north side of the Duero River, putting him closer to Bonet’s 8th Division marching from the north. Wellington followed him to the Duero but did not attack. For the first two weeks of July little happened, except for the arrival of Bonet, which made the opposing armies about equal in strength, although the British were stronger in cavalry, while the French had more artillery.

Wellington scanned the French position for an opportunity to attack, but he did not like the prospects for a frontal assault. What is more, any attempt to flank them would expose his lines of communication to the west. He was also aware that Joseph Bonaparte was gathering about 14,000 troops to march to Marmont’s aid. Marmont did not know this because Spanish guerrillas had intercepted the dispatches sent to him.

The inactivity along the Duero came to an end on July 16 when two French divisions crossed the river at Toro. Concerned that the British might be reinforced, Marmont went on the offensive. When Wellington learned the French were moving against him, he shifted part of his army to the west to deal with that threat as well as the French advance from Toro. But the advance from Toro turned out to be nothing more than a ruse to deceive Wellington.

Marmont sent the bulk of his army across the Duero at Tordesillas, which lay 20 miles east of Toro. The two French divisions at Toro crossed back over the bridge, blowing it up behind them, and marched east to cross the Duero and rejoin the rest of the army. By the night of July 17 the French army was across the Duero. Marmont had fooled Wellington. As a result, the 4th Division and the Light Division were in danger of being cut off.

The following morning Wellington took steps to extract the two exposed divisions. Shortly after sunrise he set out to make sure that they were withdrawn in keeping with his orders. When he arrived at 7 am he found a cavalry skirmish in progress. The French cavalry charged two squadrons, one each from the 11th and 12th Light Dragoons, which were protecting two guns of horse artillery.

Wellington and those around him drew their swords as the squadron from the 12th Light Dragoons broke under the weight of the charge and the squadron from the 11th Light Dragoons fell back. However, the 11th Light Dragoons soon counterattacked; in so doing, they stabilized the situation. Nevertheless, it had been a close call for Wellington. The two British divisions withdrew safely and took up new positions with the main army west of the Guarena River.

The two armies began a parallel march south on July 20 as Marmont attempted to turn Wellington’s right. The following day Wellington retreated west while Marmont turned southwest to cross the Tormes River. When the two armies bivouacked that night, a heavy rain fell on the two camps.

On the morning of July 22 the two evenly matched armies attempted to dry out from the previous night’s thunderstorm. Wellington’s Anglo-Portuguese army numbered 47,449 infantry, 3,254 cavalry, and 60 guns, and Marmont’s Army of Portugal had 46,600 infantry, 3,400 cavalry, and 78 guns.

Despite the bad weather, the British troops were in high spirits and anxious to fight, although they were annoyed at having to retreat before the French. “The idea of our retiring before an equal number of any troops in the world was not to be endured with common patience,” recalled Lieutenant John Kincaid of the 95th Rifles. But Wellington’s army would not be retreating much farther.

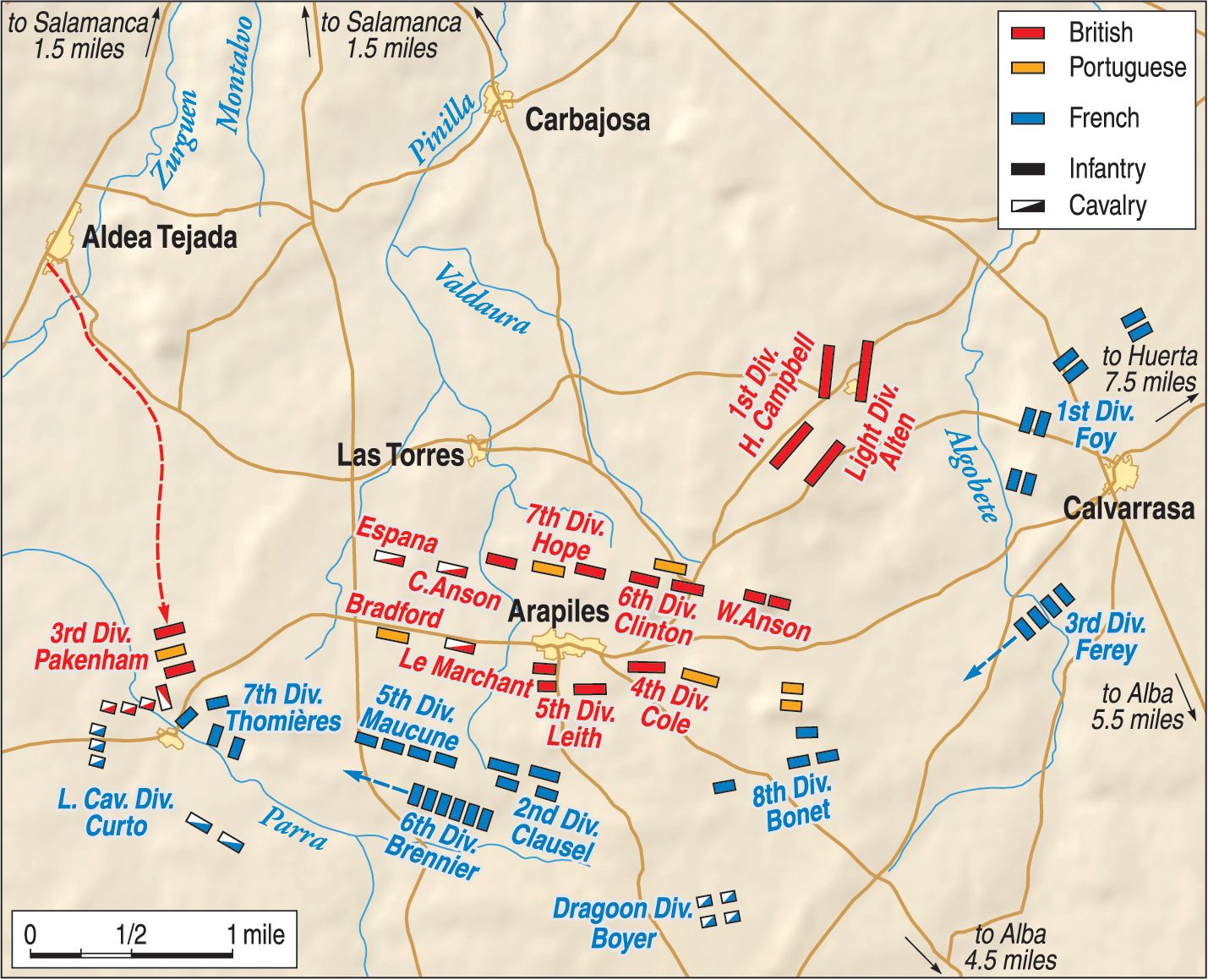

Two ridges—the Lesser Arapile and the Greater Arapile—were situated south of Salamanca. The Greater Arapile was about 300 yards long with steep sides and inaccessible rocky ends. South of this ridge was a large wooded area of low trees and rough scrub.

The Lesser Arapile was 900 yards north of the Greater Arapile. A detachment of Lt. Gen. Sir Galbraith Lowry Cole’s 4th Division had advanced onto the Lesser Arapile at dawn to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, thus making the Allied position untenable.

A skirmish had erupted at daybreak at a small chapel on the heights of Calvarrasa de Arriba where light troops of General Maximilien Sebastien Foy’s division encountered an outpost of Brunswick Oels jagers from Maj. Gen. John Hope’s 7th Division. The 68th Brigade of the 7th Division, together with the 4th Caçadores from Brig. Gen. Denis Pack’s Independent Portuguese Brigade, were quickly fed into the fray. Skirmishing between opposing cavalry spread north, but at that point the fighting did not grow into a general engagement.

Wellington intended to abandon Salamanca and fall back to Ciudad Rodrigo if Marmont continued to flank him. The British commander had been informed the night before that a brigade of cavalry dispatched by Caffarelli was riding south to reinforce Marmont and should arrive soon. But if an opportunity arose to deliver a decisive blow to the French, Wellington intended to take advantage of it before the French were further reinforced. Much to the chagrin of his troops, Wellington ordered the army’s baggage train to retreat for Ciudad Rodrigo escorted by a Portuguese cavalry regiment.

Marmont was attempting to observe the Allied line, which stretched for three miles from Santa Marta along the Tormes River south along a line of heights to the Lesser Arapile. From his position with Foy’s division, Marmont could not see much of Wellington’s army as it was “hidden from us by the chain of heights which runs from north to south,” Foy later wrote. However, they could see the Allied army’s baggage train rumbling west toward Ciudad Rodrigo.

Wellington, who was with Hope’s 7th Division, was tracking the French army’s movements. Like Marmont, he could not see much of the enemy except for Foy’s division facing him as the bulk of the French army was masked by woods located between Foy and the Tormes.

Continuing his strategy of turning Wellington’s right flank, Marmont extended his left. Bonet’s 8th Division was ordered to capture the Greater Arapile, which would guard the Army of Portugal’s flank as the troops swung west. Wellington initially had been unconcerned about the Greater Arapile as it was an isolated height and not part of the heights he held. With the growing light and seeing the French headed for it, Wellington ordered the 7th Caçadores of Cole’s 4th Division to capture the hill first.

The Portuguese light troops lost the race to the Greater Arapile. The French, who had arrived there first, drove them back with heavy fire. With this high ground in French hands, Marmont moved five of his divisions to the edge of the woods to await further orders. He also ordered General Claude François Ferey’s 3rd Division and Brig. Gen. Pierre Boyer’s dragoons to support Foy.

As for Wellington, he shifted his position throughout the day using the Lesser Arapile as a pivot of his L-shaped line with Anson’s brigade of the 4th Division continuing in its position on the smaller hill and the rest of the division a little to the west holding high ground behind Los Araphiles. Pack’s brigade was positioned between Anson and the rest of the division’s position. The Allies dragged two batteries to the top of the Lesser Arapile with considerable difficulty.

Lieutenant General James Leith’s 5th Division was positioned to the right of Cole and facing south. Supporting the 5th Division was Clinton’s 6th Division, while the 7th was withdrawn from its position north of the Lesser Arapile and placed to the rear of the 5th Division. Maj. Gen. Henry Campbell’s 1st Division, along with the Light Division under Maj. Gen Charles Alten, continued a north-south position near Calvarrassa de Arriba. Maj. Gen. Edward Pakenham’s 3rd Division along with Brig. Gen. Benjamin D’Urban’s cavalry, which unlike the rest of the army were posted north of the Tormes, were now ordered across the river to Aldea Tejada four miles northwest of Los Arapiles where they awaited further orders.

The French continued to strengthen their hold on the Greater Arapile by placing guns on its summit. This took some work as the hill was too steep for horses to drag them up, so the barrels had to be removed and carried up by grenadiers and the gun carriages manhandled to the top. Once the guns were reassembled they were in a good position to fire on Wellington’s army, especially the troops holding the Lesser Arapile. Twenty guns were also positioned on the nearby ridge of El Sierro to cover Marmont’s troops as they emerged from the woods.

Wellington watched the French maneuvering with concern, knowing they would soon be able to turn his flank. He decided at midday to attack Bonet’s division holding the Greater Arapile. The 1st Division was moved into position to attack, but before the redcoats attacked the order was cancelled. The cautious Marshal William C. Beresford, commander of the Portuguese army, had observed strong French forces to his rear and persuaded Wellington against an assault. It looked as if the French were preparing to attack, but nothing came of it.

As the day wore on Marmont believed Wellington was preparing to retreat, which was confirmed by dust clouds to the rear of the Allied army that were caused by Pakenham and D’Urban marching their troops to Aldea Tejada. At 2 pm Marmont began to extend his left flank across the heights known as Monte de Azan, located south of Los Arapiles. Leading the way was Maucune’s 5th Division, along with Brig. Gen. Jean Baptiste T. Curto’s Light Cavalry Division acting as a screening force for his advance and flank. Maucune halted on the heights opposite Los Arapiles and sent skirmishers to the southern end to attack the British holding it. French guns on the Monte de Azan and the Greater Arapile pounded the British 4th and 5th Divisions.

Supporting Maucune was Thomieres’ 7th Division along with Clausel’s 2nd Division lagging behind as a reserve. Thomieres did not stop his division behind Maucune, but instead pushed past him to the left, eventually taking the lead. This produced a dangerous gap between the two divisions. The French left flank was in no battle order and soon there was almost a mile between Maucune’s right flank and the Greater Arapile. The 122nd Ligne from Bonet’s division attempted to fill the gap, but its numbers were far too few. Foy and Ferey’s 3rd Division on the French right were two miles away.

After Marmont was severely wounded by an Allied shell, an attempt was made to pass command of the Army of Portugal to Clausel, but he had suffered a wound to his heel and was temporarily incapacitated. For that reason, command of the army devolved to Bonet, the commander of the 8th Division. Bonet was in command for only a short time before he also suffered a grievous wound. By that time Clausel had been patched up and was back in the saddle. Clausel rode to the Greater Arapile to assume command of the hard-pressed French army. The confusion regarding command of the Army of Portugal had an adverse effect on the French left flank.

Wellington was having lunch in a farmyard when he spotted the French extending their left and knew it was time to attack. He quickly mounted up and thundered toward Aldea Tejada. Upon reaching the village, he ordered his brother-in-law, Pakenham, to attack.

“Edward, move on with the 3rd Division, take those heights in your front, and drive everything before you,” Wellington said. Pakenham was supported by D’Urban’s cavalry, along with Maj. Gen. Victor von Alten’s cavalry brigade led by Lt. Col. Frederick von Arentshildt.

After giving his orders to Pakenham, Wellington galloped over to Las Torres where he ordered Maj. Gen. J.G. Le Marchant to have his heavy cavalry brigade ready to take advantage of the first opportunity to charge the French despite the hazards. Wellington then rode on to order Leith to advance his 5th Division which was to be supported on its right by Brig. Gen. Thomas Bradford’s Portuguese Brigade, which was slow in arriving and would miss much of the action. Leith was also supported on the right by Le Marchant’s cavalry. While Pakenham drove the French along the Monte de Azan, Leith and Le Marchant were to hit the French in the front. Cole’s 4th Division was to advance on the left of Leith, while the 7th Division would move into the 5th Division’s old position to support Leith from the rear.

Pakenham quickly pushed his division forward supported by a large body of cavalry. For 21/2miles the columns were out of sight of the French due to a range of low wooded hills. D’Urban rode ahead with two officers. After clearing a small clump of trees, he was startled to come upon a column of Thomieres’ infantry. He decided to attack immediately.

D’Urban galloped back to his brigade of cavalry and ordered the lead regiment, the 1st Portuguese Dragoons, which consisted of three squadrons numbering about 200 sabers, into line and led them forward. They were soon supported by 11th Portuguese Dragoons and two squadrons of the British 14th Light Dragoons of Arentshildt’s brigade, which had just arrived.

With no cavalry vedettes covering its flank, the leading French battalion was caught completely by surprise. The French managed to inflict heavy casualties on two squadrons of the Portuguese dragoons, which charged frontally, but the third squadron struck the French in their left flank. The whole battalion broke and fled up the heights chased by the Portuguese cavalry which bagged many prisoners.

Strung out on the west end of Monte de Azan known as Pico de Miranda, Thomieres’ division was in some disarray when it faced Pakenham’s division led by Lt. Col. Alexander Wallace’s brigade, followed in support by Major James Campbell’s brigade and finally the Portuguese Brigade. French guns fired on the advancing infantry, while British artillery hammered back. At that point, Allied skirmishers drove in the French skirmishers.

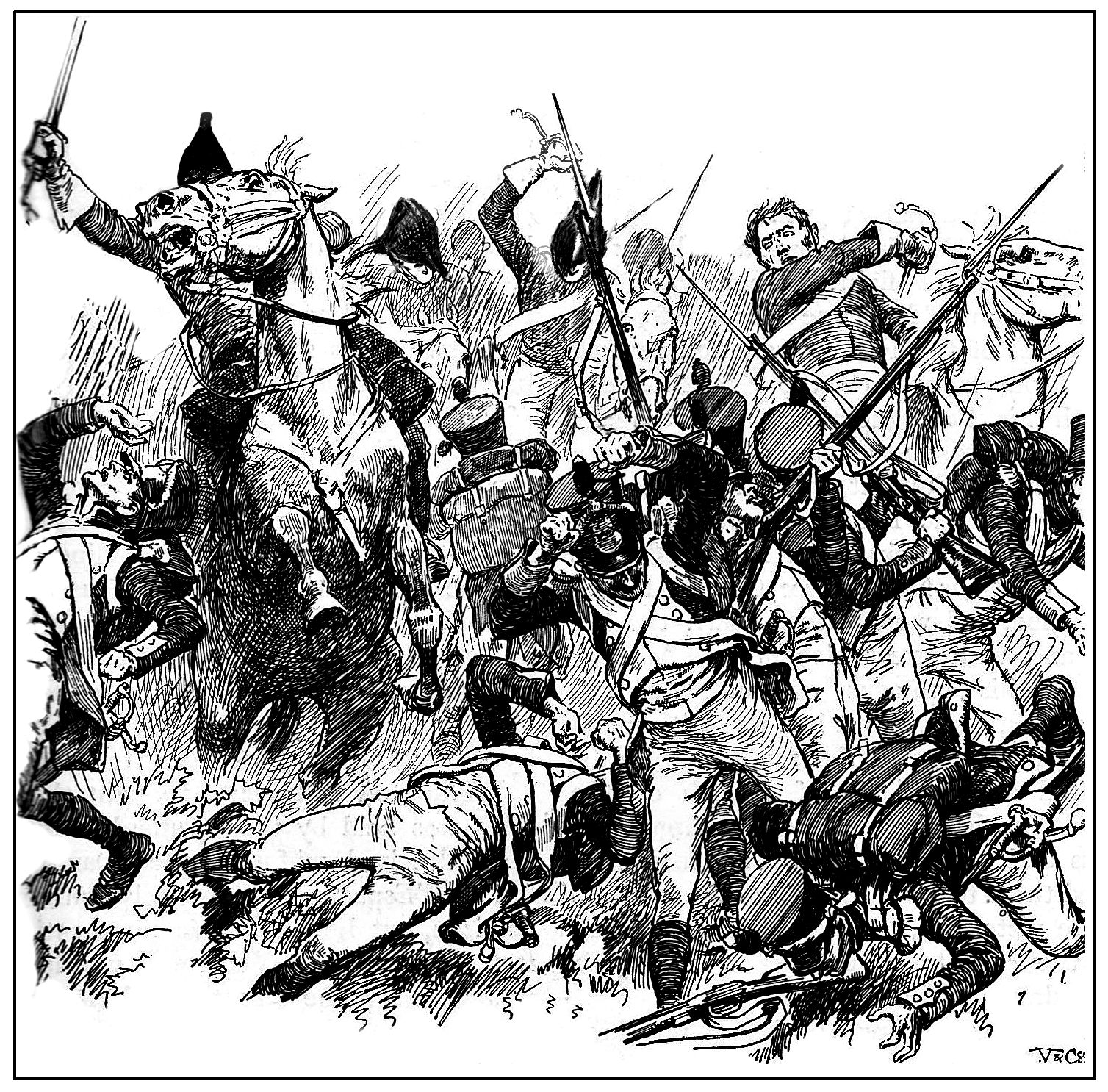

As the Allied troops reached the brow of the heights, the French advanced to meet them and let loose a deadly volley. The front rank of Wallace’s brigade was hit hard by the hail of bullets, but his determined men kept coming; this unsettled the French, who fired a poorly delivered second volley. Pakenham gave the signal, and the redcoats surged forward, intending to take their revenge on the French.

Thomieres’ division crumbled under the attack, suffering more than 2,000 casualties. Thomieres was among the slain. The survivors of the division fled east in panic as Pakenham’s division followed after them. During the Allied advance on the heights, Curto’s cavalry struck the right of Wallace’s brigade, which fortunately had enough time to prepare for the horsemen and caused them to veer away. The 1st Battalion of the 5th Regiment in Campbell’s brigade following behind was not so lucky. They were hit hard by the French cavalry and broke. The French, however, were quickly attacked by D’Urban’s cavalry and driven off. The shattered British battalion reformed after a few minutes and rejoined the advance.

With Pakenham’s attack underway, Wellington sent a staff officer to tell Leith to advance. “Thank you, Sir! That is the best news I have heard today.” Leith then took off his hat, waved, and cried, “Now boys! We’ll at them.” The men of Leith’s division, who had been enduring a French bombardment, were glad to finally be moving. The Allied skirmishers led the way at about 4:30 pm, followed by the rest of the division divided into two lines with Lt. Col. James Greville’s brigade, along with 1st Battalion of the 4th Regiment from Maj. Gen. William Pringle’s brigade in the lead. The second line was made up of the rest of Pringle’s brigade and Brig. Gen. William Spry’s Portuguese Brigade.

Leith’s men advanced steadily forward, enduring French artillery fire as they reached the heights and Maucune’s division. The French troops, which were positioned about 50 yards from the crest of the heights, formed into squares due to the appearance of Le Marchant’s heavy cavalry on the British right. They fired a volley, which was answered by a deadly one from the British. The redcoats then let out a cheer and surged forward in a bayonet charge. Maucune’s division collapsed, and the survivors fled for their lives.

Le Marchant’s cavalrymen rode toward the disaster, overtaking Thomieres. They climbed up the gentle slope and pushed along the plateau. Two regiments of Le Marchant’s cavalry crashed down on the French infantry from the 62nd and 101st Lignes of Thomieres’ division, while the third cavalry regiment struck the flank of Maucune’s division already reeling from Leith’s attack on their second line. Le Marchant’s cavalry were not done yet. The two regiments that struck Thomieres’ division raced forward and charged the 22nd Ligne of Taupin’s division. The French infantry was overtaken before they could form a square. Many were hacked down as a result.

By the late afternoon, the west end of Monte de Azan was a chaotic scene of French troops fleeing or small bands attempting to resist or escape. The British cavalry had lost all restraint and were chasing and sabering anyone they could. Unable to rally most of his men, Le Marchant joined a half squadron of the 4th Dragoons attempting to break a French square. As the thundering cavalrymen closed in on the square, the French let loose a volley that sent Le Marchant sprawling from the saddle mortally wounded. The French soldiers scrambled to safety in the nearby forest. Despite the loss of Le Marchant, the cavalry along with Pakenham and the wounded Leith had done their job. The French left was in shambles with heavy casualties, and two standards bearing the French Imperial Eagle were captured.

In the center, Cole’s 4th Division began its advance about 20 minutes after Leith had started his. As the troops marched forward, with skirmishers out front, they came under French artillery fire. Their objective was Clausel’s division, which was forming on the east end of the heights to support the guns hurling death at the British and Portuguese. To Cole’s left was Pack’s brigade, which was advancing toward Bonet’s division holding the Greater Arapile.

Looking to his left, Cole could see a lone enemy regiment, the 122nd Ligne of Bonet’s division, holding a low rocky ridge between the Greater Arapile and the plateau. To protect his flank from this unit, Cole dispatched the 7th Caçadores and possibly the rest of the Portuguese Brigade under Colonel George Stubbs to drive the French back. The French regiment withdrew back toward the Greater Arapile, and the 7th Caçadores kept a watch on them and the rest of Bonet’s division.

The rest of Cole’s 4th Division began advancing up the heights. The 2nd Brigade of Clausel’s division was waiting for them just past the crest. A tremendous crash of musketry erupted as the two sides collided. The fighting lasted for some time before the French gave way. The Allies had been bloodied in the exchange of lead, and for that reason they did not follow after the French. Cole was badly wounded during the fighting.

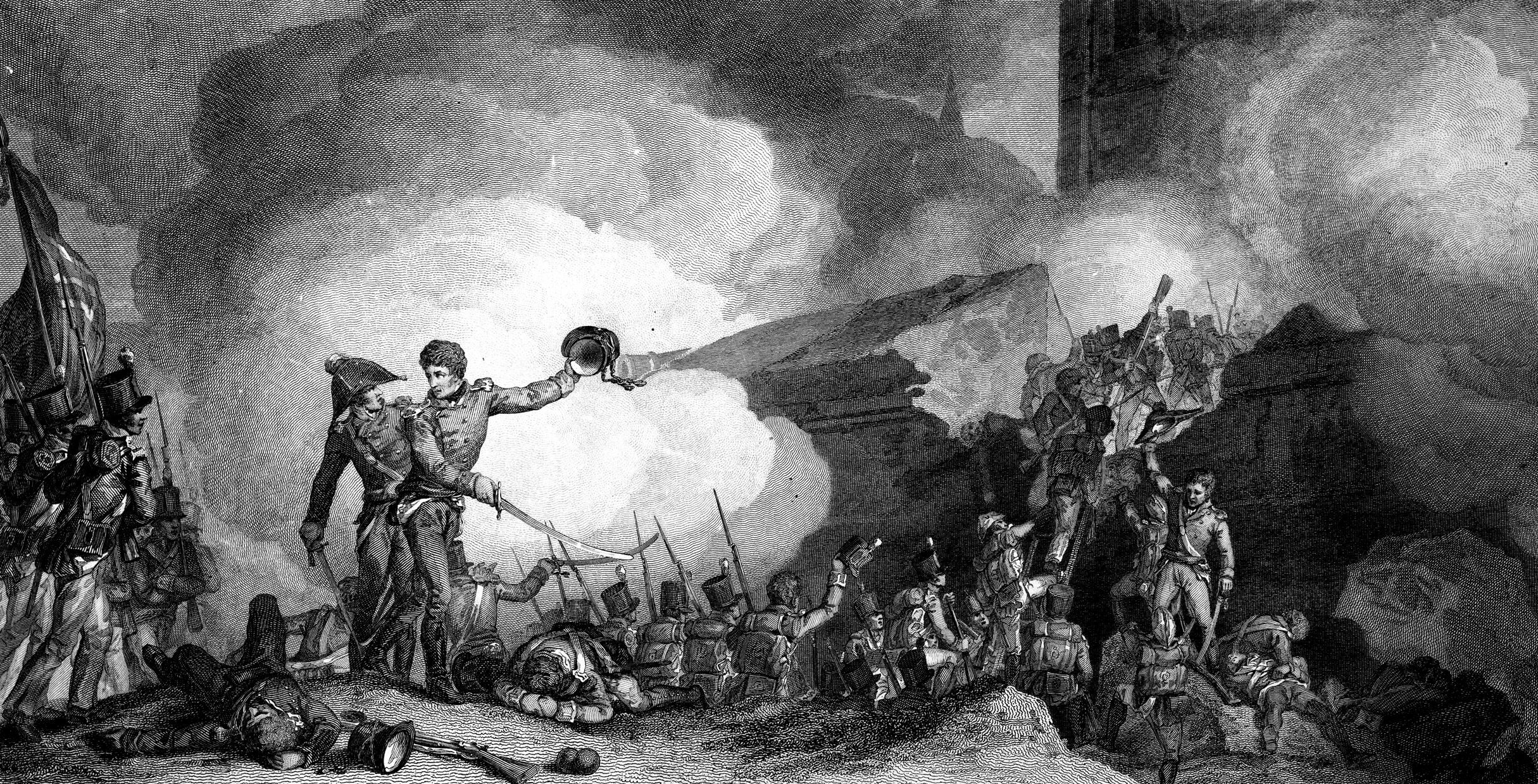

There is some debate whether Pack attacked because Wellington ordered him to attack or whether he did so of his own volition to support Cole. Whichever the case, Pack’s brigade attacked the Greater Arapile in two columns with unloaded muskets so the troops would be forced to rush the hill and not take time to shoot. Leading the way was a storming party, skirmishers, and four companies of grenadiers.

As the Allied troops struggled up the steep slope of the Greater Arapile, they were decimated by a brutal French volley. The Portuguese were flung from the hill with about 470 casualties. Cole’s 4th Division was doing little better to their right.

The remaining brigade that made up Clausel’s division counterattacked Cole’s 4th Division. At the same time, Bonet’s 8th Division, which had advanced from behind the Greater Arapile, struck the Allied flank, inflicting heavy casualties on the 7th Caçadores. Cole’s 4th Division broke, and his troops fled back down the heights toward the Lesser Arapile.

Clausel’s 2nd Division, together with three of Bonet’s four regiments and three regiments of Boyer’s dragoons, were advancing after the broken Allied troops, inflicting more casualties upon them. The French horsemen galloped ahead after the broken 4th Division, but had only limited success against the division as many of its troops were beginning to rally and form into squares or made it to the safety of the 6th Division, which had arrived to fill the gap. The eastern end of this division held by the 2nd Battalion of the 53rd Regiment was hit hard by the French dragoons, but repulsed them.

The French counterattack was brought to an abrupt halt by Clinton’s 6th Division, which struck them in the front and drove them back. In addition, the French were struck in the flank by a Portuguese brigade from the 5th Division that Beresford led into action.

The 6th Division continued to push forward, overlapping Bonet’s regiments and driving them back in disorder. Both Clausel and Beresford were wounded in the bloody contest of musketry. The French troops ultimately gave way and were in full retreat.

The French abandoned the Greater Arapile as the 6th Division advanced past it on the west, while the light companies of the King’s German Legion Brigade from the 1st Division advanced on its east flank. In an attempt to buy precious time to allow the shattered French divisions to escape through the woods and scrub to the south, Clausel ordered Ferey to position his fresh 3rd Division on El Sierro, a low ridge southeast of the Greater Arapile. Ferey had orders to hold until nightfall to prevent a full-scale disaster. Ferey deployed his nine battalions, which were supported by 15 guns, on the ridge in a single line three ranks deep with the flank battalions formed into squares to guard against cavalry.

Clinton was given the task of taking the ridge. He halted his division within sight of the French position to rest and reorganize. Unfortunately, he stopped within range of the French guns and his men suffered because of it. On Clinton’s left the Fusilier Brigade of the 4th Division rallied, while to his right were the 3rd and 5th Divisions both now reforming.

In the gloaming, Clinton began his bold advance on the French-held ridge. As the Allied line closed in on the ridge the French greeted it with a murderous fire that swept away whole sections of Clinton’s force. The 6th Division returned fire and a vicious exchange of musketry raged. Dry grass ignited by the sparks from the guns burned up the face of the hill, giving the landscape an eerie appearance. Although the French army continued its withdrawal, it managed to repulse the Portuguese Brigade of the 6th Division.

Ferey was killed as British gunners sent shot and shell into the French ranks. The retreating troops sought cover in nearby woods. Clinton’s exhausted 6th Division did not pursue. Foy’s division on the French right fell back safely, covering the right flank of the battered army that was stampeding through the woods.

Knowing the enemy was headed for a bend in the Tormes River where there were only two crossings, Wellington believed they would cross at the fords at Huerta. There was a bridge at the Alba de Tormes, the other crossing, but it was guarded by a castle held by a Spanish battalion. At midnight Wellington was shocked to discover that the French were crossing at Alba where, unbeknownst to him, the Spanish garrison had withdrawn.

The Army of Portugal had escaped, but it had been badly bloodied. The French army had suffered 12,500 casualties and lost 20 guns. Wellington’s losses were considerably less, with 5,000 killed, wounded, or missing.

As the Army of Portugal retreated east it had more pain inflicted on it the next day at Garcia Hernandez, where the King’s German Legion broke two French squares, inflicting more than 1,000 casualties in a sharp rearguard action.

Wellington broke off his pursuit at Flores de Avila on July 25. Shortly afterward, he marched to Madrid, entering the city on August 12. Because of the loss of Madrid and the defeat at Salamanca, Soult received orders to lift the siege of Cadiz and join King Joseph at Valencia on the eastern coast of Spain.

As for Wellington, his stay in Spain was not permanent. After the siege of Burgos was abandoned due to a shortage of supplies, Wellington’s army withdrew to the Portuguese frontier for the winter. The following year Wellington would return to central Spain. This time he would defeat the French on the Iberian Peninsula once and for all.