BACK STORY: The author has always had a soft spot for the story of the Mulberries. His mother, who was a skilled maker of wedding dresses in London, was conscripted to learn welding and sent to Jones’ Cranes, at Letchworth, just north of the capital city. In American terms she became Rosie the Riveter. A few years ago, he discovered that Jones was the company contracted to make the cranes that would unload the ships at the Mulberry harbors.

Then the author learned that Allan Beckett, the designer of the floating roadways that, come hell or high water (literally), brought the goods ashore, was a former pupil at his school, East Ham Grammar, in London’s East End. This gave him a personal interest in the subject and one that he never missed the opportunity to expand on whenever he takes school parties or visitors to the cliff tops overlooking the remains of Mulberry B—alias Port Winston—at Arromanches, France, also known as Gold Beach.

Brave men win wars. On D-Day they jumped out of C-47s, crash-landed in gliders, and stormed out of landing craft, dueled with minefields, barbed wire, and any form of ordnance that the enemy could throw at them. They emptied clips and magazines at everything that moved, but with each fateful ping from their M1 Garands they knew they would be closer to running out of ammunition unless they had a reliable supply chain to back them up.

Brave men also have to rely on engineers, planners, and the right sort of politicians to crack the whip when required and ensure that their front line kept moving. All of the combat drills practiced so diligently in the run-up to June 1944 would have been pointless without the work being undertaken simultaneously by Churchill, Britain’s War Office, and the Admiralty to provide them with material support by building artificial ports to be installed on the D-Day beaches.

Gooseberry and Mulberry harbors sound like unlikely heroes. If your weapon of choice has a name like bazooka or Marauder, you feel that you have a head start in dealing with the opposition. However, for the liberation of Normandy and ultimately the whole of France and Europe, the contributions of these artificial harbors that supplied troops post-D-Day with a lifesaving supply route have ranked with the service rewarded by a Victoria Cross or a Medal of Honor, not to mention a Purple Heart or two when the forces of nature joined forces with the enemy.

Our story begins with the miracle of Dunkirk. As soon as Churchill’s rescue mission was completed, he began planning for the day when British and Commonwealth troops would be back on the French beaches. He probably hoped that they would be accompanied by their American compatriots, but in 1940 that was wishful thinking. His immediate concern was to prevent a German invasion of Britain, increase arms production, and ensure that the country was not starved into submission.

If Britain survived this onslaught and reached a position where an invasion of Europe became possible, it was clear that the enemy would already have built defenses along the French coastline. In particular, they would have fortified the existing ports where troops would be able to disembark in large numbers and where large supply ships could unload the precious cargoes they needed to penetrate further into enemy occupied Europe.

Britain held on, was joined by the United States in December 1941, and managed to defeat Rommel in North Africa in the fall of 1942, enabling Churchill to allow himself a little optimism: “This is not the beginning of the end, but it may be the end of the beginning.” His caution was partly conditioned by the results of the failed Dieppe Raid (Operation Jubilee) in August 1942, when the Allies discovered exactly what would happen if they tried to capture one of the Channel ports.

The joint Anglo-Canadian raid occupies a place in history as a very painful wound costing 70 percent casualties, but military planners were able to turn this negative into a positive. The eventual plan to invade Europe, Operation Overlord as it would become known, would not include a part of the coastline where the Allies would have to capture a port.

Vice Admiral John Hughes Hallett, the leader of the Dieppe Raid, stated categorically after the raid that capturing a port would be impossible, and that one would have to be brought across the English Channel. After the raid, he became chief of staff at the War Office, and slowly a plan for that very thing began to take shape. Some ideas had already been submitted for artificial harbors by leading naval civil engineers.

The planners would also try to convince Hitler that the invasion would take place at Calais, but it would actually happen on the sandy beaches of Normandy. There was just one problem: once the landing craft had dropped divisions of assault troops on to the beaches, where would the supply vessels, requiring deep water and port facilities, be able to discharge the equipment necessary for the invasion to progress inland?

Churchill’s record in World War I, especially after the disastrous Dardanelles campaign, was not one to attract superlatives from historians, but one of his ideas, which had to be shelved at the time, was to provide a starting point in the search for a solution.

It consisted of a plan for the construction of temporary deep-water harbors off the Dutch-Danish coast. In 1941 this was resurrected and expanded by a group of forward-thinking civil engineers. A new department, Transportation 5, was set up at the War Office under Brigadier Bruce White, who channeled the ideas of these engineers into a plan that was eventually to become the Mulberry Project.

In addition to the War Office, the Admiralty and Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations also played a role in the planning. Predictably, there was a range of opinions on how best to proceed—and plenty of conflict between engineering experts, politicians, and the military.

It was estimated that the advancing army would need to be supplied with 12,000 tons of equipment and 2,500 vehicles each day. Like the early experiments with flying machines, a project of this scale was something that had never been tried before. But unlike the development of manned flight, the development of the mobile harbor labored under severe time constraints and a desperate need for secrecy, all while fighting a global war.

There was also a view articulated by Admiral John Leslie Hall, Jr., once the United States became involved, that the large LSTs (Landing Ships, Tanks) could do the job without the need for artificial harbors, although their operation would be dependent on the daily tides. In fact, the LSTs performed well on the latter half of D-Day, and some military historians still argue, hypothetically, that they could have provided all the supplies needed by the liberating armies.

However, there were some decisions that could be agreed upon. Sites were chosen on the west coast of Britain, in southern Scotland on the Solway Firth, and North Wales at Morfa where the coastline had sufficient similarities to Normandy to allow initial engineering experiments to take place. Part of the labor supply came from military personnel, but because many of the fit young men with the necessary practical skills were already serving their country overseas, a fresh supply of construction workers had to be found and trained in double-quick time.

Construction camps were set up, and men and women—some of them refugees from war-torn Europe—worked in secrecy to advance the testing of the project prototypes. Initially the focus was on floating roadways and pier heads without the consideration of breakwaters. Progress was slow, resulting in increasingly frustrated memos from Churchill to find a structure that could rise and fall with the tide.

At the same time, the British Royal Navy was taking a closer look at the French coast. Initially, the planners had begun collecting old photographs and holiday postcards of the beaches and matching them with reconnaissance photographs to get an idea of the topography and beach defenses. They also began looking at the Normandy tides, which rose and fell 21 feet twice a day.

Next, a series of clandestine forays in the dead of night brought back sand, mud, and rock samples to help understand the geology. As well as confirming that the water would be deep enough for a harbor, they had to ensure that heavy vehicles, once landed, would not get bogged down on the sand.

Major Logan Scott-Bowden of the Royal Engineers one night took a motor torpedo boat to investigate part of what was to become Sword Beach, swimming ashore under cover of darkness, knowing that capture would have serious consequences.

Subsequently, a daring mission involving a midget submarine brought back vital information from Vierville (Omaha Beach) to be fed into the project that was evolving on Scotland’s Solway Firth. As a result of these efforts, scale models of the projected landing beaches were constructed and the plans moved on apace.

After the dangerous reconnaissance, the months spent on the drawing board, and the experiments that were played out under a cloak of total secrecy, the final decisions were made.

The project then moved into the construction phase, another breathtaking exercise in logistics. The final go-ahead was given on September 4, 1943. Two artificial harbors would be created; Mulberry A would be located on Omaha Beach to supply the western end of the invasion area, and Mulberry B would be installed at Gold Beach at Arromanches-les-Bains to supply the eastern end of the D-Day beaches.

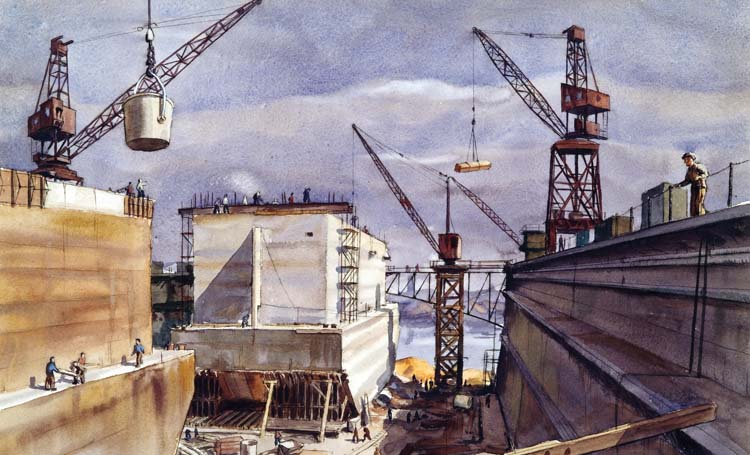

To build the two massive artificial harbors, 300 companies were commissioned, involving over 40,000 pairs of hands, many of which were not possessed of construction skills. But if car factories could produce aeroplanes, seamstresses like the author’s mother could become welders, and young farm hands could build reinforced concrete structures.

Locations were chosen around Britain for specific sections of the project that would eventually come together as one dynamic jigsaw or Lego monster. The huge concrete caissons would be built in new dry docks on the estuaries of the River Clyde in Scotland and on the Thames downstream of Blitz-torn London.

The metal floats were constructed in Kent in southeast England and along the south coast in areas around Southampton. Existing bases on Scotland’s Solway Firth and Morfa in North Wales also continued to play a role.

The whole construction project was completed in a mere six months, an amazing achievement, and although it was carried out under the strictest secrecy, there were one or two security scares.

The worst came when the British traitor and renegade broadcaster William Joyce (alias Lord Haw Haw) announced that the enemy knew all about the concrete structures that were being constructed to be sunk off the coast to create harbors. He then went on to say sarcastically that the Germans would save the British forces the effort and sink them themselves.

This caused alarm but not panic, and the British code breakers at Bletchley Park set to work intercepting any messages that could indicate how much the Germans knew. Eventually one was found that indicated they believed they were simply antiaircraft towers.

In light of what appeared to be a serious breach of security, a further precaution was taken. Alongside the planning for Operation Overlord was a deception plan (Operation Fortitude) that was developed to convince Hitler that when the inevitable invasion took place, it would be in the Dover-Calais area, the shortest distance between England and France. To reinforce this bit of misinformation, a concrete caisson was towed to the English coast near Dover.

Some descriptions of the structures produced are confusing because of the codenames used, but an account given on the Combined Operations website is very lucid and does not overwhelm with engineering jargon. It also has some excellent appendices containing primary source material and tables of statistical detail.

The basic structure was a ring of breakwaters with three entrances for the cargo vessels. Once in this sheltered environment, the ships would unload onto piers and the supplies would be transported to the shore by trucks traveling along floating roadways. There were three major components to the structures: breakwaters, piers, and roadways.

Breakwaters had three components. The first was the cross-shaped bombardons that were floating breakwaters, anchored in place, and forming the first point of resistance to the waves and tides of the English Channel.

Next to these were the huge, concrete caissons, codenamed “Phoenixes,” which were hollow inside so that, once the valves were opened, they could be sunk into position. There were a total of 146 of these Phoenixes; they were 196 feet long, 59 feet high, and 49 feet wide.

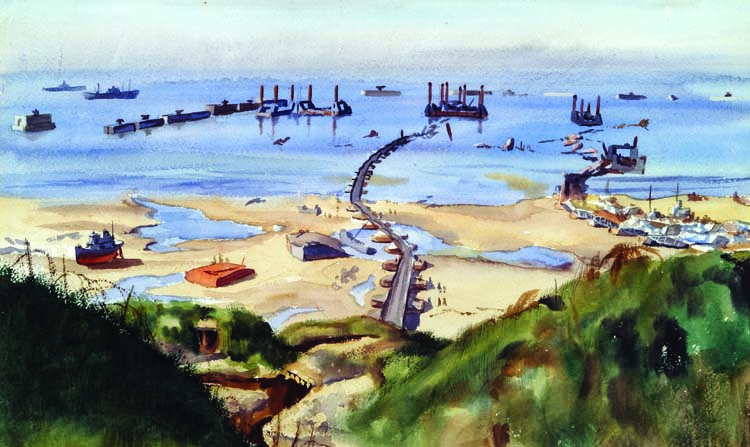

Although not exactly visible from space, a brief look at Google Maps today provides an instant understanding of how durable these structures proved to be and gives an immediate impression of the actual scale of Mulberry B. Visitors to Gold Beach at low tide can easily absorb this vista from the viewing platform in the cliff-top parking lot or walk out to them.

The final piece of the breakwater jigsaw puzzle was an armada of old ships (known as “block ships”) that crossed the Channel, many under their own steam, and, in a final act of service, were scuttled in relatively shallow water to complete the ring of resistance. Within this ring there were three gaps (north, east, and west entrances) for the supply ships to enter and exit. The scuttled ships were codenamed “Gooseberries,” and there were 70 in total.

Although a number of the old ships were employed at the two Mulberry harbors at Omaha and Gold Beaches, the majority were used as breakwaters at Utah, Juno, and Sword to assist with the unloading of LSTs.

Once inside the breakwaters, the ships and barges would anchor at a pier head to unload. Codenamed “Spuds,” these were held on the seabed by four stout legs. They were built with platforms that could be electrically raised and lowered in relation to the tide and were connected to the shore by Allan Beckett’s floating roadways.

Roadways represented the phase of the construction project that took the most time to perfect. Sections of roadway, 80 feet long and codenamed “Whales,” were attached to floating pontoons called “Beetles.” These concrete-and-steel structures had to support the 56 tons of the whale—plus a further 25 tons whenever a tank crossed over them. The roadways were connected to the beach by a buffer or approach span. Power-driven pontoons called “Rhinos” were also constructed to bring other supplies ashore.

After the war, many of the roadway sections were conveniently recycled as bridges to cross some of Normandy’s rivers. Close to where the author used to live in Pont Farcy, the river Vire was spanned by one of the whales from Mulberry B. It was replaced in 2008, saved by a group of enthusiasts, and placed in a local picnic area beside the river for visitors to appreciate. Many of the others form part of open-air museums at Arromanches and the Vierville Draw at Omaha Beach.

Planning D-Day was an enormous exercise in logistics. In addition to training the first-wave assault troops and arming the ships and planes whose shells and bombs would support the landings, the planners had to find ways of organizing and storing the trucks, jeeps, tanks, tents, medics, and other support staff who would follow through once bridgeheads had been established.

The roads and villages of southern England were full of men and machines. (One wag said that the vast numbers of barrage balloons floating over Britain’s ports and shipyards were the only things keeping England from sinking.) At the beginning of June it was estimated that there were three million troops in southern England, ready to invade Europe. This approximates to the total population of Mississippi.

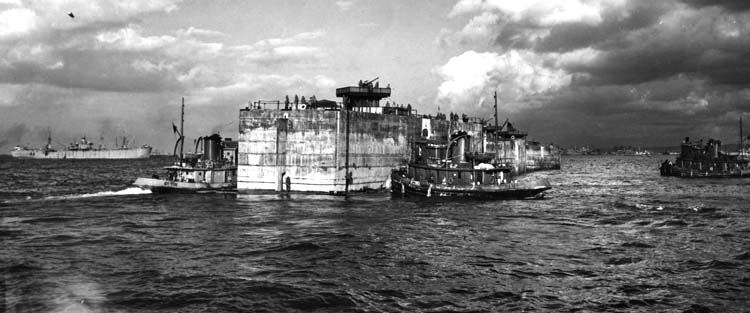

As D-Day drew near, at Lee-on-Solent close to the Isle of Wight, a fleet of tugs waited for instructions for what became known as Operation Corncob. These tugs had been requisitioned from the United States and Britain to steer the components of the Mulberries into position as soon as the troops had landed.

Anticipating a date of June 5 for D-Day, the tugs sailed on the 4th and assembled together in the English Channel. Bad weather delayed the assault, but Eisenhower made the momentous decision to go for it on the 6th. By D+1, they were anchored five miles off the French coast while calculations were made from high ground on land and from high-water marks on the beaches of Omaha and Gold for the alignment of the piers. Marker buoys were also placed in the planned locations for the lowering of the concrete caissons and the scuttling of the block ships to create the breakwaters.

Next, the order was given for the block ships to sail, under the command of Lt. Col. Landsdowne, RN, to the locations where they would be sunk as breakwaters—a task that was made easier by the Luftwaffe who sank two of them in just the right spot off Omaha Beach!

The tugs at this point were also under enemy fire, although the more rapid progress made by troops inland from Gold Beach meant the tugs at Mulberry B could function with less hindrance. The journey for the tugs was a difficult one, being limited to a maximum speed of five miles per hour. In all, a total of 400 units were tugged across the English Channel, no less a flotilla than the assault force that had preceded them.

At Utah, Juno, and Sword Beaches, other block ships were sunk to create the Gooseberry harbors that would act as breakwaters to assist with the supply of men and materials via smaller vessels. The role they played was significant and helped to take the pressure off Mulberries A and B. At Utah Beach in particular, they made a major contribution to supplying U.S. troops and were operational until November 1944. (This story is well described and displayed to visitors at the recently expanded Musée du Débarquement Utah Beach.)

At the two Mulberries, the outer ring of protection was created by the bombardons, which were towed into moorings on June 6 that had already been positioned by boom-laying craft. Unfortunately, an error in calculating the depth of the water resulted in their being located in deeper water than had been planned, and they formed a single rather than a double barrier, giving less wave protection.

The caissons, including a two-man crew and an antiaircraft gun team, arrived on June 7 for the tricky maneuver that would set them into the positions, which some of them still occupy. Their valves were opened and they sank to the seabed. The tops were between 10 and 30 feet above sea level, depending upon the tides, and barrage balloons and antiaircraft guns were affixed to the structures to deter any enemy planes that took an interest in them.

The investment in gunners on the caissons proved its worth when Mulberry B was targeted by 12 Messerschmitts in mid-July. After a sustained duel, only three of the planes returned home.

On the night of June 19, the Normandy coast was subjected to the worst storm in living memory. It came from the northeast—the worst possible direction—and continued to pound the coast for three days. The storm only damaged Mulberry B at Gold Beach, but at Omaha Beach, the harbor was irreparably destroyed. Ships were blown into the concrete caissons, which subsequently broke up.

The breakwaters, however, did manage to provide shelter for many vessels that would otherwise have been destroyed, and some supplies did get through. On the worst day of the storm, 800 tons of petrol and ammunition were unloaded at Arromanches, together with hundreds of fresh, if seasick, troops.

There is an even deeper significance to the date of June 19, as it was the next alternative for D-Day. One consideration for Eisenhower, when his chief meteorologist consulted the tide tables and weather forecasts to decide whether or not to postpone the original plan, was the next date when the tides were favorable. The advice he received was to select June 18-20. The consequences of a postponement to these dates would have been even more devastating to the campaign to reclaim Europe than the destruction of Mulberry A.

As the storm subsided, American troop landings at Omaha reverted back to the methods used on June 6. Landing craft and ships ran onto the beach and sailed back with the rising tide. This actually worked better than expected, and some of the salvageable parts of the harbor were used to strengthen Mulberry B.

Mulberry B, which became known as Port Winston, soon began to play its part in winning the war. Initially, it was used for unloading stores, but following Patton’s breakthrough at Avranches and the British Operation Bluecoat, which drove great wedges through Hitler’s defenses, the port became a major conduit for troops to enter Europe.

During the week of August 14, when German troops were in full flight toward the Falaise Gap, 24,000 of the 34,000 British soldiers who landed in France arrived via the port.

Throughout the late summer and fall as Paris was liberated, and as Patton characteristically accelerated his tanks toward Germany, the area around Gold Beach and the little town of Arromanches became a frantic hive of activity to supply the push eastward.

The capture of Cherbourg at the end of June meant that a major French port was in Allied hands, but the German Army had so thoroughly wrecked and mined the facilities that American engineers had to work night and day through the end of August to make it usable. Even then, it was at the far western end of Normandy and was of limited value as the Allied forces had driven farther eastward.

By November, with the capture of Walcheren, the Belgian port of Antwerp became available, and the Allies could begin a new supply line closer to where the action was taking place. Mulberry B could then heave a sigh of relief and enjoy a place in history.

The statistical records speak for themselves: during the five months that it was operational, Mulberry B provided a gateway to Europe for two million servicemen and 500,000 vehicles. In addition, four million tons of supplies were unloaded to support the liberation.

From an engineering perspective, it was equally impressive: the harbor eventually contained a structure of 600,000 tons of concrete, 31,000 tons of steel, 33 jetties, and 10 miles of floating roadway.

Another logistical engineering marvel that often gets overlooked is the contribution of PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean). Without sufficient quantities of fuel, the mechanized Allied armies would have ground to a halt shortly after reaching Normandy. Therefore, like the Mulberry Project, engineers had been secretly working on an ingenious way to keep fuel flowing from Britain to France.

Two separate plans were developed. The first was basically a large, three-inch flexible hose that looked more like an undersea communications cable than an oil pipeline. Carried aboard ships on huge reels, the pipeline was laid from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg—a distance of 70 miles—on August 14, 1944.

The second PLUTO relied on 20-foot sections of three-inch steel pipe that was, like the flexible hose, coiled around huge floating spools code-named “Condundrums.” These deployment systems weighed 1,600 tons each and were pulled by three tugboats from the British terminal at Dungeness to the French port of Boulogne, 31 miles away. As the spools unwound, the pipe settled to the bottom of the English Channel.

Between the two PLUTO systems, a million gallons of fuel per day could be delivered to the Continent.

The Mulberry Project belongs among those near-miraculous events like Dunkirk, the Dam Busters Raid, and the war in the Pacific that succeeded against all odds to bring an end to the most costly war in history.

It attracted a few critics, however, especially after the storm that destroyed Mulberry A at Omaha Beach meant that the unloading of supplies had to carry on regardless and succeeded without an artificial harbor.

However, it must be remembered that Mulberry B was fully operational and contributing daily to the supply chain with increasing levels of efficiency and could be confidently relied on, whatever the weather conditions. It was as if a plane had crash-landed on one engine. It had landed and everyone was safe!

The value of the contribution of the Mulberry and Gooseberry harbors is beyond question, but even before D-Day, the project was creating spinoffs that would be useful elsewhere. Many people believe that it indirectly assisted with the development of the LSTs, which were then in their infancy, and that the procedures developed at Mulberry B provided the basis of the roll-on, roll-off ferries used globally today.

Working under pressure within enormous logistical and time constraints forced engineers to come up with solutions to problems that would have other uses. Aside from the logistical value, the morale boost that this successful project gave to the Allies at a crucial time is incalculable.