By Don Roberts

During the Civil War western Virginia was crucial to the Union. The region that lay west of the Shenandoah Valley and north of the Kanawha River held nearly a quarter of Virginia’s nonslave population when the war began in 1861. Since the first pioneers had pushed across the mountains and settled the western lands of Virginia, grievances had existed between them and the “Tidewater aristocrats” to the east who governed the huge commonwealth. An unfair tax structure that benefited the slave-owning eastern counties, coupled with the fact that the vast majority of the state’s roads and railroads were constructed in the east, contributed to the desire for the creation of a separate state.

At the time of Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, seven states had already seceded, and there was much talk of others leaving the Union as well. Lincoln had to keep a hold on Maryland—it was unthinkable to have the nation’s capital surrounded by Rebel territory. Keeping a major Union presence in western Virginia was almost as important. Controlling the regions would help prevent an assault against Washington from arising up its ridges, and it would help protect the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, a vital part of the North’s line of communication with the western theater of operations.

Following the war’s outbreak, citizens in western Virginia voted against Virginia’s secession by three to one. By summer 1861 the Wheeling convention in the west had formed its own “restored government” of Virginia and considered the new Confederate government in Richmond illegal. The convention selected new officials as well as a new governor, Francis Pierpoint. President Lincoln recognized the new Virginia government. On July 13, 1861, two U.S. senators and three new congressmen took their seats in Congress, all from the state of Virginia.

As the political situation evolved in western Virginia, the military situation began to take shape as well. By early November 1861, General William S. Rosecrans secured much of western Virginia when he forced Confederate General John B. Floyd to withdraw all Rebel forces from the region. From then on, western Virginia remained in Northern control. The only exception was an occasional Confederate raid and a never-ending guerrilla campaign waged against Union forces. As Union infantry commander Robert H. Milroy wrote, “We have now over 40,000 men in the service of the U.S. in Western Va. … [but] our large armies are useless here. They cannot catch guerrillas in the mountains any more than a cow can catch fleas. We must inaugurate a system of Union guerrillas to put down the rebel guerrillas.”

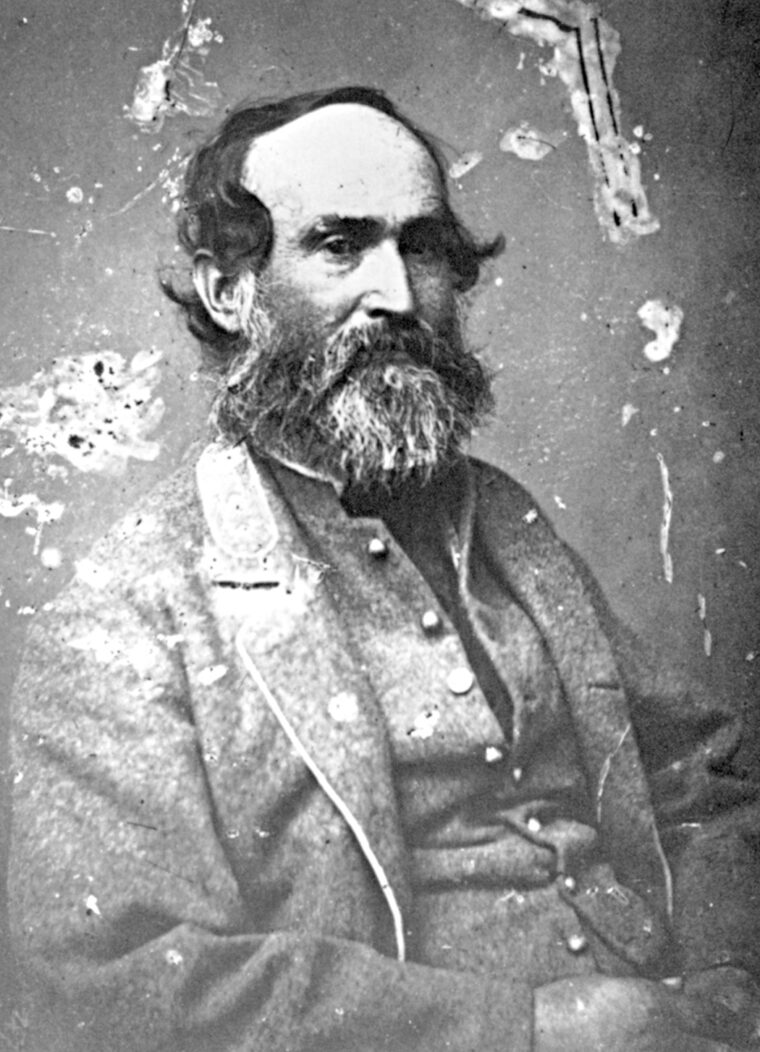

Following a period of relative quiet in the Federal outposts throughout western Virginia, the Confederates completely surprised Union garrisons on April 21, 1863. General Robert E. Lee had long advocated cavalry raids into Union territory to interrupt the B&O Railroad, while at the same time recruiting both men and supplies for the Confederate war effort. Riding out of the Shenandoah Valley, Generals William Jones and John D. Imboden led separate columns with surprising speed and effectiveness. While Jones’s men severed the B&O at several locations, Imboden’s troops moved with almost total freedom throughout the area gathering horses, cattle, and other provisions of all types. This successful Jones-Imboden raid took nearly four weeks, during which the Confederate raiders traveled several hundred miles.

The Rebel incursion sent a ripple of anxiety throughout the Federal government. After reviewing the events, Union generals agreed that more cavalry units were needed to guard against these types of raids in the future.

The few cavalry units that existed in western Virginia before the Jones-Imboden raid had been scattered around the region and attached to various infantry commands. The commander-in-chief of the Union Army at the time, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, considered western Virginia a backwater with its small villages and rugged, mountainous roads. As a result, he “dumped” commanders and troops of questionable ability into the region. Certainly “Old Brains” never considered placing valuable “front-line” cavalry there. His opinion was that if commanders in western Virginia desired cavalry, “they would have to provide it themselves.”

If there was to be a cavalry force capable of preventing another Jones-Imboden-type raid, or capable of pursuing an enemy force once a raid had occurred, then converting existing infantry into cavalry troops was the only solution. Although Halleck’s opinion of “mounted infantry” was that they were a “mongrel force, the poorest troops in the world,” he nevertheless authorized an entire brigade of “mongrel” cavalry—the dire circumstances demanded it.

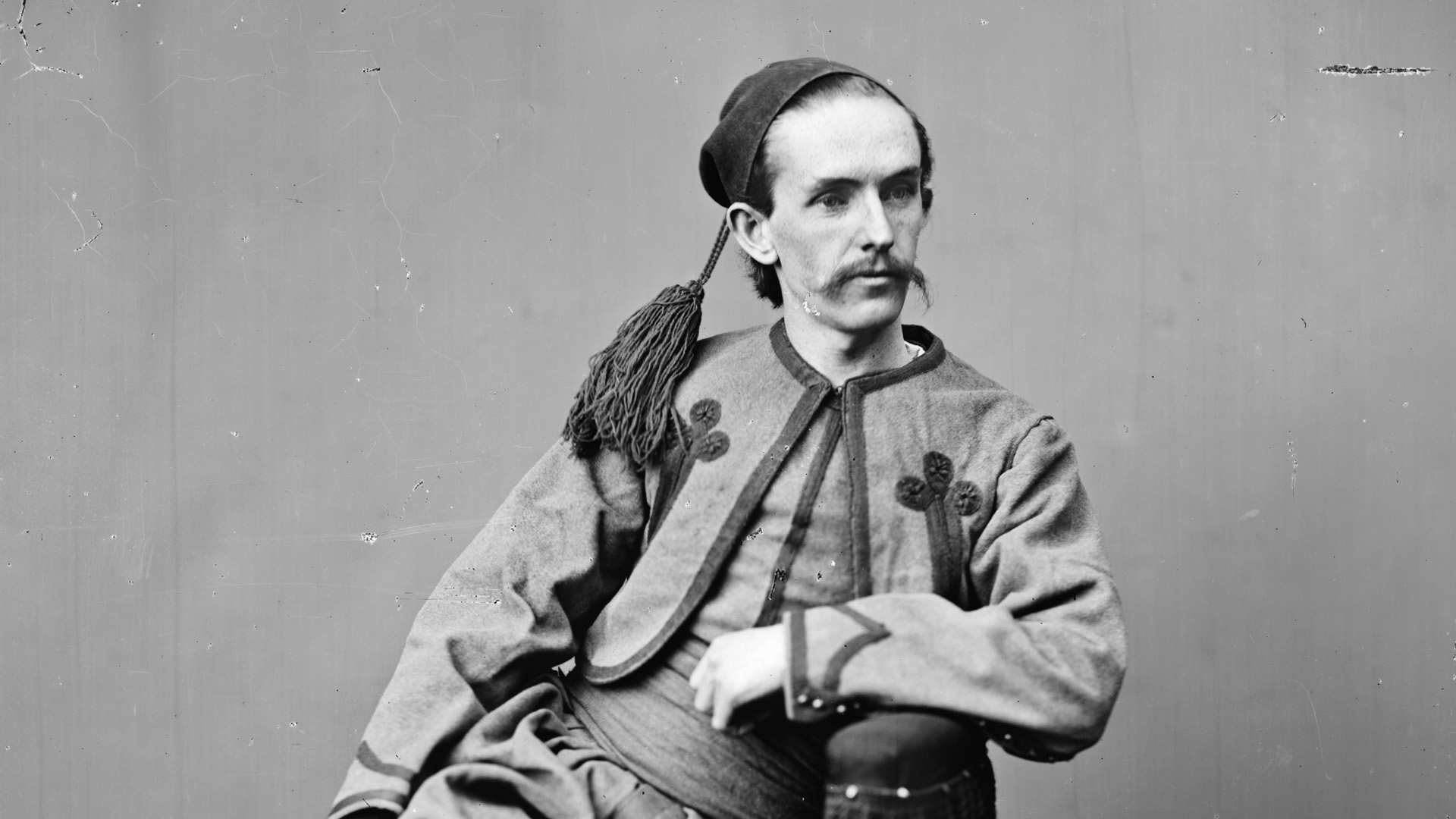

In fact, at the time of the Jones-Imboden venture, a brigade of cavalry did exist. The Fourth Separate Brigade had been scraped together from veteran units around the area and was charged with defending the loyal counties in western Virginia. This they had failed to do. The Fourth’s first commander, General Benjamin S. Roberts, stood by totally confused while Jones and Imboden rode with impunity throughout the region. Consequently, General Robert Schenck, commander of the Union’s Middle Department, which included the region of western Virginia, sent General William Averell, a veteran cavalry officer, to relieve Roberts and take over command of the Fourth Separate Brigade.

By the 19th century many people believed that cavalrymen led a leisurely existence. They rode to battle while the infantry plodded their way down endless miles of winding roads. Many considered the soldier on horseback to be a kind of aristocrat when compared to the infantryman.

Actually, nothing could be further from the truth, and Averell knew it. Because the infantry settled into their camps for extended periods between campaigns, and to wait out bad weather, they spent countless days of inactivity. Life was different in the cavalry camp. Cavalrymen usually saw some sort of activity daily. When not directly involved in battle, troopers scouted, demonstrated against enemy positions, carried messages, escorted field officers, conducted reconnaissance, and cleared the route of march for the main army when it moved.

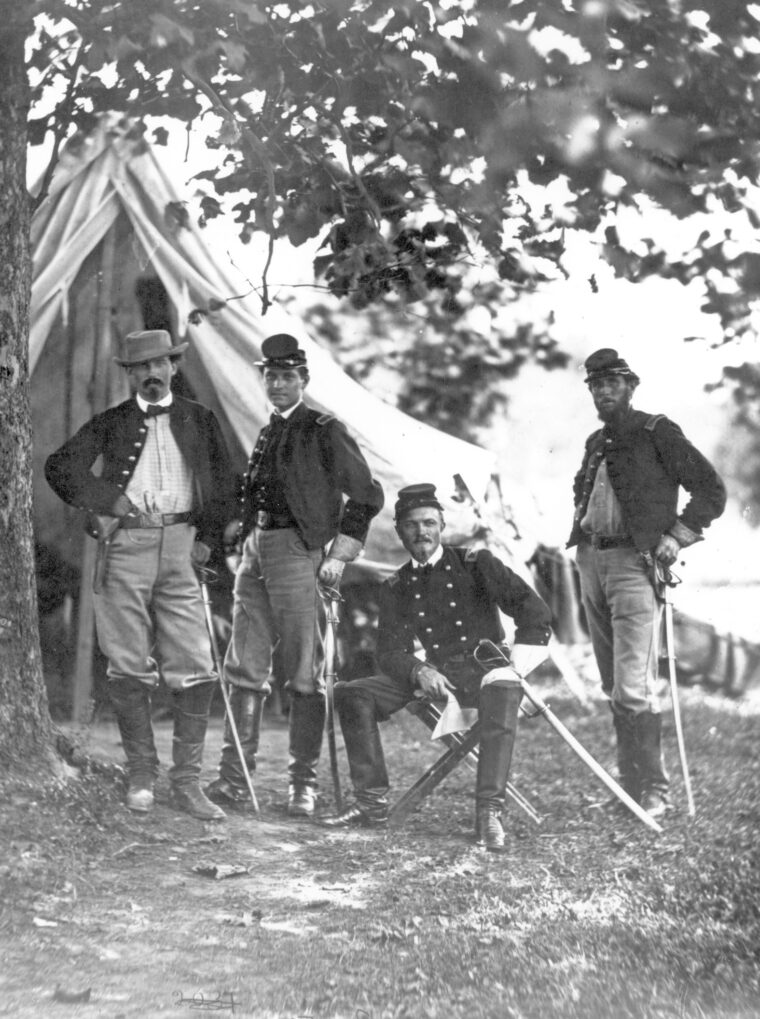

Arriving in Weston on May 22, 1863, Averell was “hailed with demonstrations of genuine rejoicing” by most of the men and officers; the general’s reputation as a competent cavalry officer had preceded him. Averell was pleased to discover a cavalry brigade of “loyal, courageous fighters,” but was dismayed that they were also undisciplined in tactical cavalry maneuvers and barely equipped with sufficient armaments, clothing, and general-issue necessities.

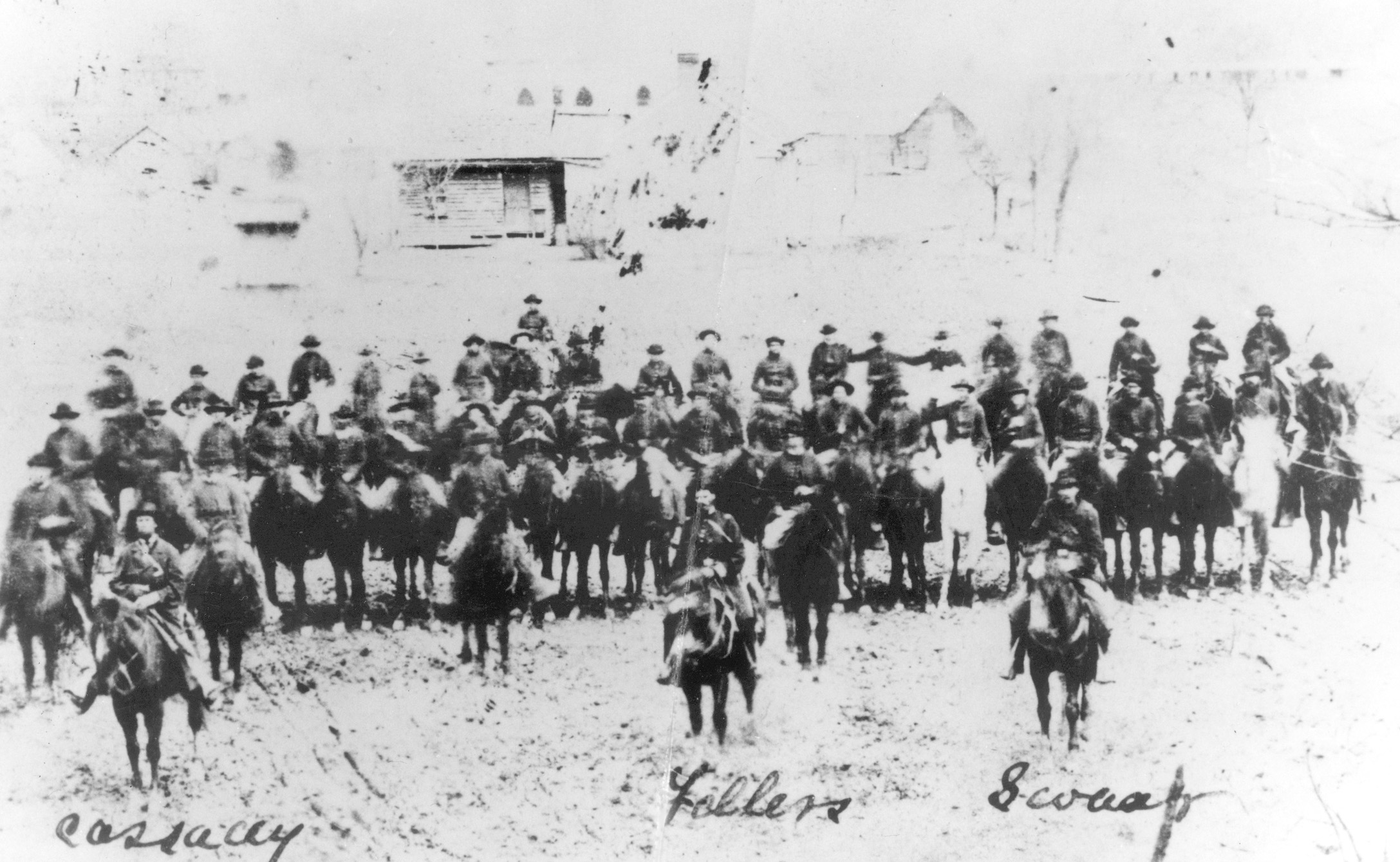

Accordingly, Averell began training the first week of June and had equipment and mounts sent to the Fourth’s training camp outside Clarksburg. Although most of the men had seen combat, none had experienced the “demands” that were now being placed upon them. One of the Fourth’s troopers remembered that “he [Averell] was an excellent drillmaster with proper views of what constituted real discipline.” Along with drilling in squads, troops, and battalion-sized formations, Averell was determined to train each of his soldiers to “care for their horses, arms, and equipment.”

By the third week of training, the U.S. Congress admitted the new state of West Virginia to the Union. As a result, all military units received new names. “Virginia” was not to be utilized any longer. The Fourth Separate Brigade became the First Separate Brigade but was commonly known as “Averell’s Brigade.” The newly created Department of West Virginia, which contained some 23,000 men, was commanded by General Benjamin F. Kelley.

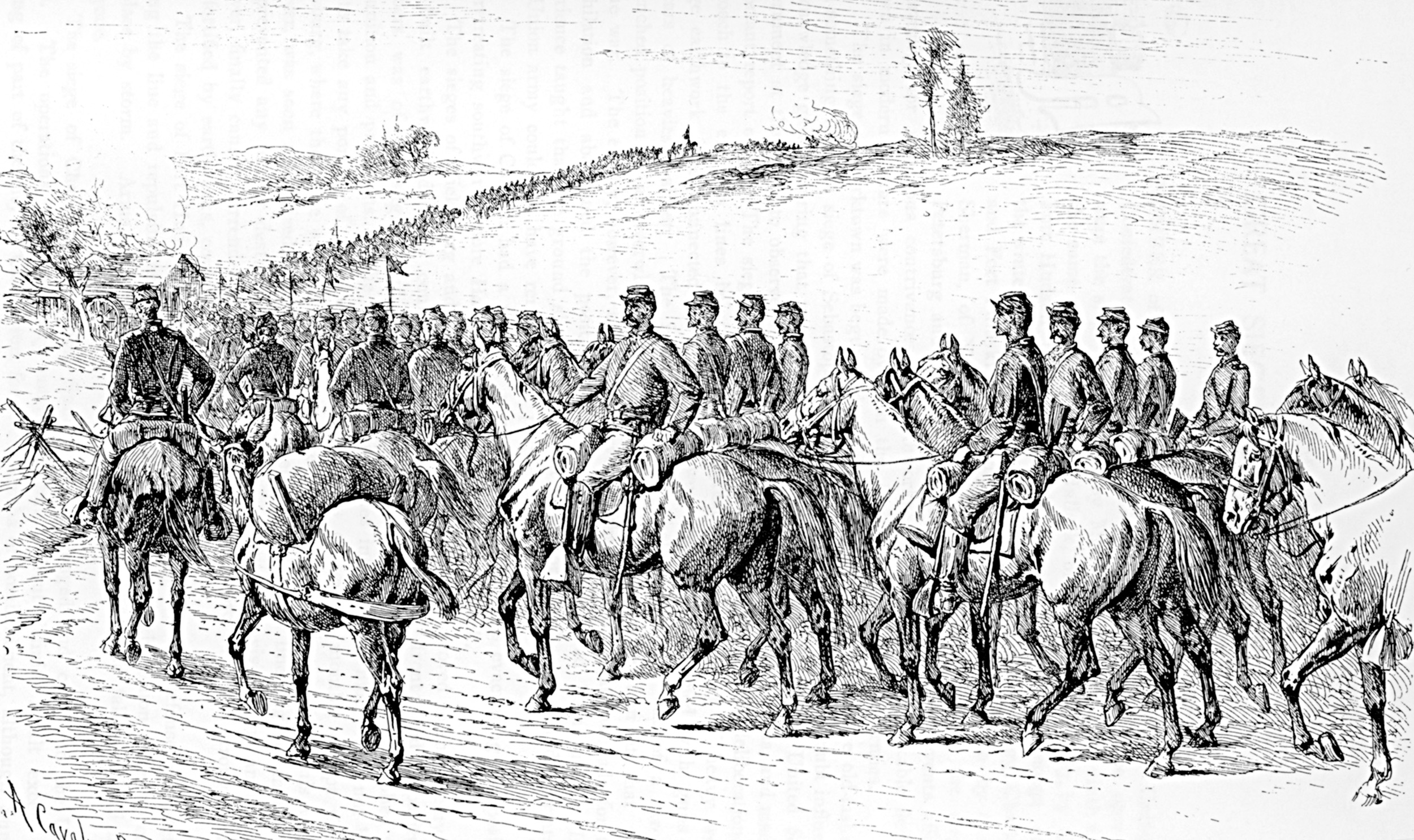

When Robert E. Lee advanced into Pennsylvania in July, he ordered troops under General Samuel Jones’s Department of Western Virginia to demonstrate toward West Virginia and then block any Federal thrust into the Shenandoah that might threaten Lee’s left flank as he moved north. Kelley dispatched Averell to repel the invaders. Riding with the 3rd and 8th West Virginia Regiments as well as the 14th Pennsylvania, Averell skirmished with the far-right flank of Jones’s line and drove the Confederates back across Cheat Mountain. The next day, July 4, Averell’s Brigade was ordered east to help cut off Lee’s retreat from Gettysburg. Riding 80 miles in three days, the troopers learned they had missed Lee’s column by less than 24 hours.

Impressed with his cavalry, Kelley next assigned Averell’s Brigade to ride 170 miles to the end of the Greenbrier Valley, capture Lewisburg, and return with the contents of the law library there as a symbol of the spoils of war. Supply difficulties dictated that Averell’s men would only be able to carry 35 rounds of ammunition each. Averell was reluctant to start the mission underprepared. Nevertheless, on August 18 he rode southward with 1,300 men.

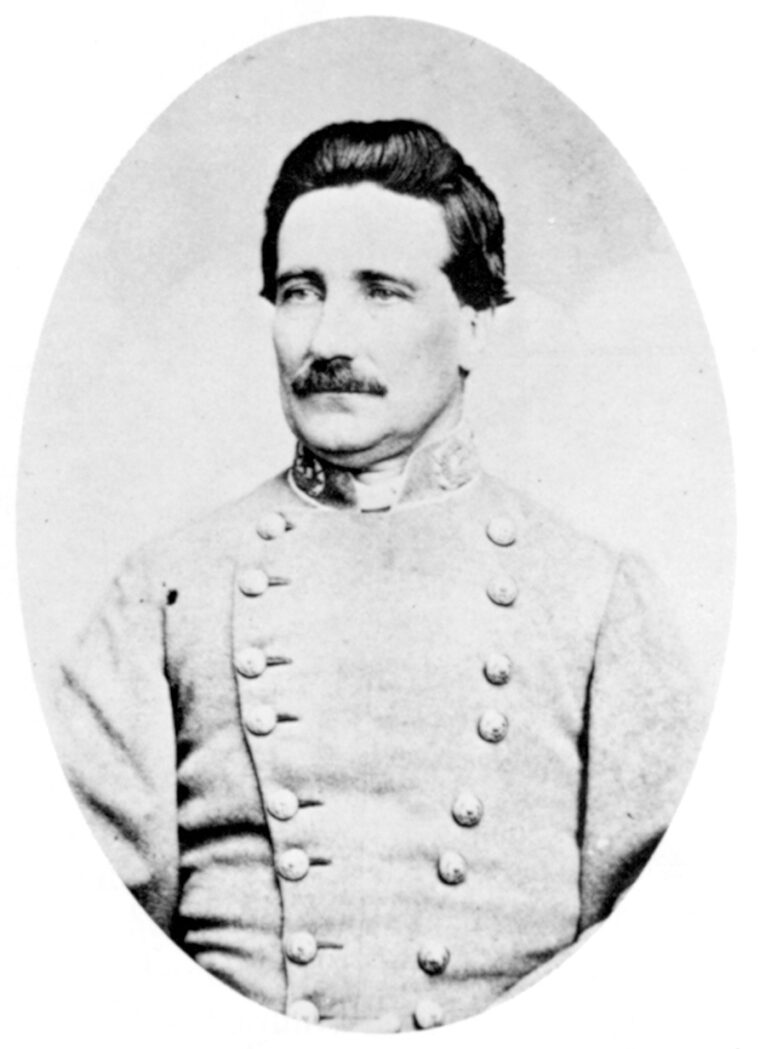

Raiding through the towns of Monterey, Huntersville, and Warm Springs, Averell’s men were intercepted by Confederates under the command of Colonel George S. Patton (grandfather of World War II’s Patton) before they could reach Lewisburg. Following a day-long fight in which they ran out of ammunition, Averell’s men were forced to withdraw. Averell pushed his men hard the next day to avoid capture. Although they failed to reach their objective, the Federal cavalrymen had fought well and conducted a well-disciplined retreat in the face of a strong enemy force.

In November, Kelley sent Averell back to try to clear the Confederates out of the Greenbrier Valley. In the Battle of Droop Mountain, Averell and his men executed a brilliant envelopment of the enemy’s left flank, but then withdrew before a decisive Union victory could be achieved; however, the Confederates did withdraw from the valley within a short period of time.

Although General Halleck was as pleased with Averell’s accomplishments as Kelley was, Halleck wanted a different kind of success from his mounted arm in West Virginia. “Old Brains” wanted Averell’s Brigade to concentrate on missions that were more strategic. One of the commander-in-chief’s primary objectives was the disruption and, if possible, severance of the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. Halleck viewed this rail line as a significant Confederate link between the western and eastern theaters of war.

Following Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg, General James Longstreet was ordered west with two divisions to reinforce General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. What followed was the stirring Confederate victory at Chickamauga as well as successive Rebel sieges of Chattanooga and Knoxville. As Longstreet besieged Knoxville, much of his logistical support was shipped along the Virginia & Tennessee.

With much of Jones’s command scattered, or with Longstreet at Knoxville, Halleck realized that a stretch of track on the Virginia & Tennessee lay unsecured. On November 29, Halleck cabled Kelley: “The greater part of Jones’s force is now at Knoxville, Tennessee, and there can be very little opposition to a movement against the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.”

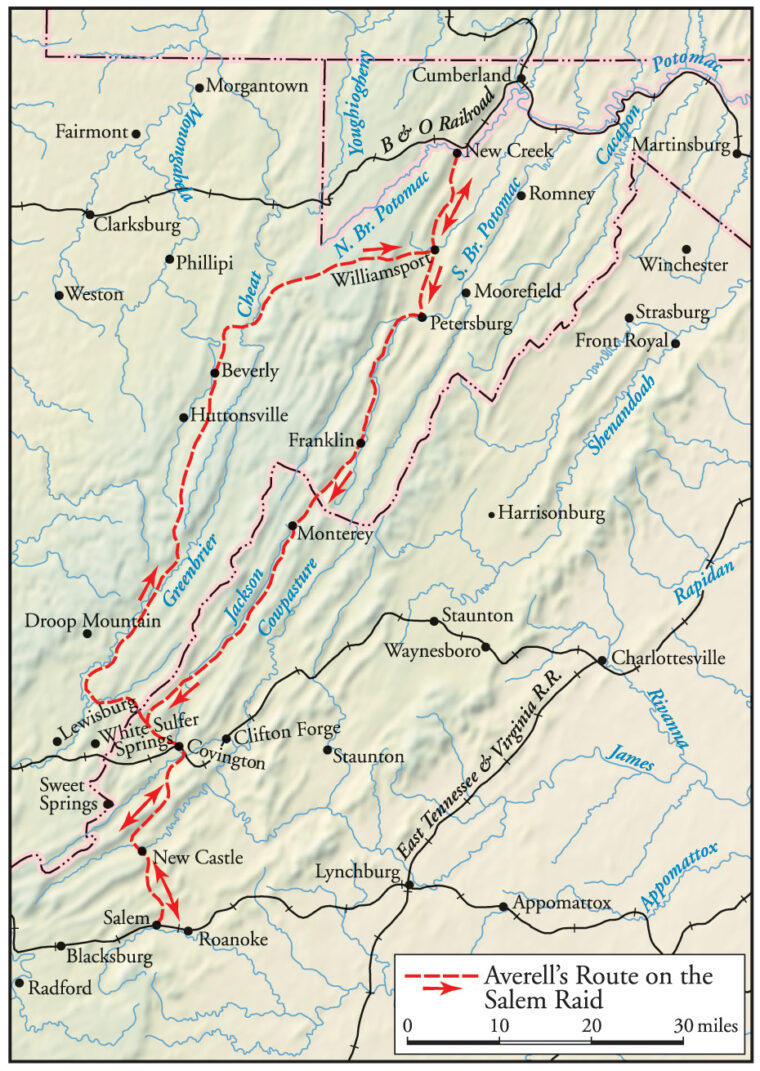

By December 5, Kelley had formulated a plan in which Averell’s Brigade was to ride some 200 miles south and strike the undefended railroad, either at Salem in Virginia’s Roanoke County or at Bonsack’s Station in Botetourt County.

Many Union commanders believed that in order for a cavalry raid to be considered a success, it had to cause damage to enemy property and have a significant impact on the strategic outcome of a campaign. In this case the strategic objective was to sever Longstreet’s line of communication from the east, thus forcing him to lift the siege at Knoxville.

When news of the impending raid reached Averell in New Creek, he immediately voiced his concerns about the duration and timing of the intended raid. With winter fast approaching, the brigade had been preparing for winter quarters. Even the most basic necessities such as horseshoes and nails were in short supply. The prospect of encountering the cruel, relentless, and harsh mountain winter was a very real consideration as well.

But Averell’s biggest concern was the lack of support his men would receive during the raid. Consequently, in a meeting between Averell and Kelley, both commanders agreed to broaden the scope of the mission to include supporting the Union horse soldiers with four separate columns.

As the fast-paced preparations for the raid progressed, Longstreet lifted the siege at Knoxville when General William T. Sherman advanced from Chattanooga. But as Longstreet settled into his winter quarters near the Tennessee-Virginia line, planning for the Averell raid continued. Kelley and Averell believed that severing the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad would still effectively cut Longstreet off from Richmond and Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Severing the railroad would deny Longstreet logistical support and make it difficult for him to move his force back east to link up with Lee.

On the morning of December 8, which dawned uncharacteristically mild, Averell’s column rode out of New Creek. Included in the line of Union men were the 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry under Lt. Col. Alexander Scott, the 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry under Lt. Col. Francis Thompson, the 8th West Virginia Mounted Infantry under Colonel John Oley, the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry under Lt. Col. William Blakely, Major Thomas Gibson’s Independent Cavalry Battalion, Captain Chatham Ewing’s Battery G, 1st West Virginia Light Artillery (four guns), and nearly 120 supply wagons and ambulances.

Averell’s supporting and diversionary units were all to be in place by the 11th or 12th of December and remain in their respective positions until the 18th. A brigade of General Eliakim Scammon’s 3rd Division was to seize Lewisburg and “deceive and detain the enemy” by demonstrating southward. Colonel Augustus Moor was to march south with the 10th West Virginia and 28th Ohio and occupy Frankfort. Colonel Joseph Thoburn’s Infantry Regiment was ordered to rendezvous with Averell’s column at Petersburg, march south with the cavalrymen to Monterey, and then remain there with Averell’s train. He was then to demonstrate toward Staunton. Finally, Colonel George Wells was to move a brigade of infantry and cavalry south from Harper’s Ferry. His men were to remain in Strasburg until the 16th, take Harrisonburg on the 18th, and then threaten Staunton on the 20th and 21st.

Although Averell received the support he had wanted, the raid still worried the commander. The distance alone was intimidating—200 miles one way. It was a route through rugged mountain roads and across several deep streams void of bridges. Bad weather could be harsh and punishing to the troopers as well. Another concern was bushwhackers. These first cousins to the Revolution’s Minutemen were always on the lookout for enemy formations to ambush or snipe. All things considered, “Averell knew this would be a highly dangerous undertaking requiring a grueling test of endurance and skill.”

Averell overcame the doubts he felt about the mission when he considered his soldiers. He realized that the “officers and men of the command were now tough, experienced, well-trained veterans possessed of invaluable qualities necessary for dealing with the dangers and uncertainties of a long raid into enemy territory.”

Preparations for the raid had been as thorough as possible in the limited time given; however, there had not been sufficient time to shoe the brigade’s mounts before the 8th. Consequently, the column had to shoe on the run as the troopers rode toward Williamsport. That first night in camp, the blacksmiths’ forges were kept bright as they worked through the night.

For the raid on Salem, Averell decided to allow his scouts, who rode well ahead of the advance guard, to “disguise themselves in civilian or even Confederate clothing,” knowing full well that if the scouts were captured they could be put to death for spying. Averell decided to rotate the duties of advance- and rear-guard details because the strain of such a stressful responsibility would be too much for the same men on such a long raid. Averell placed the wagons and ambulances in the rear of the column rather than in the usual place in the center. In the event of an emergency in the front, Averell wanted the entire column to be ready to move ahead at once.

After two days, the raiders had ridden 42 miles. Thanks to the fine weather and good roads, Averell’s men reached Petersburg with sufficient daylight remaining to allow them to search for “wood, water, [and] grass,” the three basics Averell considered important for any cavalry camp.

On the third day, the troopers managed the 32 miles down to Franklin. Clearly they were in enemy territory now. Many of the Yankee troopers commented that the people living here “looked daggers at us.” Aside from the hostile manners of the local inhabitants, two unfortunate events happened on the morning of the 11th, the column’s fourth day. While on picket duty in the early morning, Benjamin Starr of Company K, 3rd West Virginia, was shot in the leg by a bushwhacker. By dawn, the temperature had fallen drastically. Now Averell’s men faced two enemies.

By the end of the day, the Union raiders had nearly reached the halfway point between their home base at New Creek and their objective; they had ridden a total of 98 miles to reach Monterey. The raiders knew that, from this point on, the dangers would increase by the minute. Averell ordered all “unnecessary encumbrances” discarded or returned to New Creek. Only the bare essentials would be carried on the saddles now. The horses were fed the last of the forage. They would eat strictly off the country for the remainder of the raid. Averell decided to keep 35 wagons to carry the tents that would be necessary to protect the men from the harsh mountain weather.

Before breaking camp on the morning of December 12, three more troopers on picket duty were shot by bushwhackers. Partly as a consequence, Averell decided to sacrifice speed for stealth, now that his men were “stripped for the race.” He turned the troopers off the main road and began to follow back roads and lanes, hoping to remain undetected. Although speed was a vital requirement for any successful cavalry raid, so was remaining hidden from the enemy for as long as possible.

As the raiders rode through the backcountry it began to rain. It was a hard, cold rain mixed with sleet and snow. Thus began a week-long series of downpours that flooded the mountains. It would turn out to be the worst flooding in the region for decades.

The principal country lane that Averell followed soon turned to thick mud, and Back Creek, which ran next to the lane, soon reached flood level. For two days the column was slowed while it crossed and recrossed the freezing waters of Back Creek 13 times. Averell considered the misery worth it because he believed the column remained undetected.

Nevertheless, Imboden learned of Averell’s column and assumed the Federals were heading for Staunton. He immediately ordered his men south toward the suspected target. Closer to Averell’s raiders were Colonel William Jackson’s men, a portion of whom were surprised by the Yankee troopers. Following a brief pursuit, the West Virginians captured four wagons filled with ammunition and supplies belonging to the 19th Virginia Cavalry. These were the first trophies of the raid.

Averell now realized that his position was common knowledge to the enemy. Consequently, speed became more important. Leaving Gatewood’s on the 14th, Averell led his men back to the main road.

The crisscrossing of Back Creek had left many of the raiders with cases of mild hypothermia. Frostbite began to take its toll, and many painfully swollen feet began to appear in the ranks as well. But through the suffering, the troopers managed 22 miles, reaching Callahan’s by 4 pm.

Learning that his covering force was in place to the west, Averell quickly decided to point his men in the direction of Salem now that his right flank was secure. At this point, Averell decided to conduct a “false advance” by sending 200 men riding hard to the east. They were then to return in a stealthy manner. As his men moved deeper into enemy territory, Averell decided to ride at night as well. Now was not the time to relax; Averell tried to employ as many tricks as he could think of to deceive the enemy.

It was 2 am when the raiders left Callahan’s. The rain had stopped but the air was frigid, and the night was inky black. At 10 am Averell called a halt to feed the horses with the plentiful forage while the men ate a quick breakfast. Averell received a message from his scouts with discomforting news: Scammon had withdrawn from Lewisburg and Moor had withdrawn as well. This left Averell’s right flank exposed and his line of communication threatened.

Averell’s reaction was to begin moving once again—Confederate General John Echols and his cavalry were only 15 miles west. Averell’s route took his men up Sweet Springs Mountain and as the troopers climbed up, around, and through rugged terrain, the temperature steadily dropped.

Most of the Union men had never seen country this wild and rugged. Seeing an occasional cabin off in the distance astonished many of the men, who wondered who could survive in such wilderness. Sometimes a few of the troopers would stop and pay a visit out of curiosity. On one such visit, Captain Jacob Rife from the 8th West Virginia stopped at a cabin just to get warm for a few minutes. Going inside, he was met by a couple with sleeping children scattered around the room. The two “lively talkers” were inquisitive about the captain, his uniform, and his equipment. But at one point the husband asked Rife, “Stranger, whar is your horns?” The wife kindly reminded her husband that “Yankees were human critters like the rest of us.”

By 9 pm on the 15th, after 17 hours in the saddle, Averell called a halt at the top of Pott’s Mountain. Although the men now were only 43 miles from Salem, the numbing cold, frostbite, and hypothermia had begun to take an unbearable toll. The horses began to collapse under the severe conditions as well. As mount after mount went down with each passing mile, men had to keep up the best they could on foot.

Learning that General Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry division was now in pursuit of his brigade, Averell sparked his men to liven their step with the news that a train carrying Confederate troops was due in at Salem at any time. Although Echols threatened from the west, Lee was coming on from the east, and Salem might be well defended, Averell remained determined to ride on and complete the mission.

At dawn on the 16th, now only a few miles from Salem, Averell selected two 3-inch gun crews and 350 men armed with repeating rifles for the final assault. When everyone was mounted and ready, the raiders made the dash for Salem.

At 10 am—after eight days and 219 miles—the Federals stormed into Salem. Rife remembered that “with little sleep and little food, in the midst of the most fearful mountain storms of wind and rain and sleet, a constantly-falling thermometer, and swelling streams—amid all these we had moved forward and gained our purpose.”

Riding into Salem, the troopers found their arrival surprised no one. In fact, during the night a cable had arrived alerting the town that “a large number of Yankee troopers had passed Sweet Springs and were headed [your] way.” Averell’s men caught many of the townspeople trying to relocate much of the military stores hidden throughout the hamlet. At the same time, a number of the residents were at the station waiting for the train from Lynchburg.

Averell’s first order of business was to cut the telegraph wire leading out of town. Although the telegraph operator had run away without sending any messages, the wires were severed nonetheless. Next, the cavalrymen rushed to meet the troop train that was expected at any moment. (In reality there was no troop train—the expected arrival was a regularly scheduled train.) Within minutes, one of the 3-inch guns was in position, and just in time. The train’s whistle sounded, and when the smokestack came into view the gun’s commander, Corporal A.G. Osborne, fired a round that damaged the stack. Immediately the train began to slow down. By the time the second round was ready, the engine had passed the gun. The gunner nevertheless touched off his piece and sent a ball flying through one of the train’s cars. Quickly, the locomotive reversed direction and chugged away before the crew could do any more damage.

Having won the “Battle of Salem,” the raiders cheered wildly. They then turned their attention on the huge volume of supplies bundled neatly at the train station awaiting shipment. The Yankees could not believe their eyes. A quick count indicated there were nearly “1,000 sacks of salt, 2,000 barrels of flour, 2,000 barrels of meat, 10,000 bushels of wheat, 50,000 bushels of oats, and 100,000 bushels of shelled corn.” Stacked nearby was more: “bundles of clothing, bales of cotton, harnesses, saddles, shoes, tools, oil, tar, rice, soap, and candles.”

Before setting torches to the Confederate stockpiles, Averell directed his men to take anything they could carry but only if they would not be slowed. The next order of business was the destruction of the Virginia & Tennessee line. Averell sent wrecking crews east and west to destroy as much of the line as possible. Huge fires were started to heat the rails so they could be bent and twisted out of shape. In all, the blue-clad wrecking crews destroyed 15 miles of track, burned five bridges, and destroyed a half-mile length of telegraph line.

After six hours of destroying and confiscating valuable property (which included hundreds of horses), Averell ordered recall. As the men reconcentrated, they began spreading rumors of false routes they would travel back to the north, and of their strength in numbers.

At a little past 4 in the afternoon on the 16th, Averell’s Brigade of exhausted men—most had not slept in 32 hours—began riding north out of town. Within minutes “a cold rain began to fall.”

To try to trap Averell’s raiders, Jones called in some 11,000 Rebels under the commands of Generals McClausland, Echols, Lee, and Imboden and Colonel Jackson. Infantry and cavalry units were being shipped from as far away as Fredericksburg, Va.

Following a few hours of sleep, the column was up the next morning and riding into the face of a freezing rain and a bone-chilling north wind. By noon the raiders were halted by a heavily swollen Craig’s Creek.

The men of the 14th Pennsylvania watched from the bank as the swift current dislodged and carried away trees. “Bewildered, tired, and confused,” the men refused to start into the icy water. Averell rode up, saw what was going on, and plunged into the swift current on his horse. Upon reaching the other side, Averell turned in his saddle, raised his hat, and shouted, “Come on, boys!” The 14th let out a whoop and “plunged in after him.”

The men of the 14th all made it across, but the West Virginia regiments did not fare as well. As more and more troopers rode into the strong current, many horses were struck by large chunks of ice, which sent both horse and rider tumbling down the creek, often to their freezing demise. To make matters worse, bushwhackers hidden in the brush across the swollen creek began taking shots at the struggling troopers.

Within the next 12 miles, Averell’s Brigade crossed and recrossed Craig’s Creek seven times. The result was numerous cases of frostbite accompanied by swollen and blackened feet, which for many of the troopers spelled amputation following the raid. “The weather was so cold, part of the time below zero, that the clothing of the men was frozen stiff soon after leaving the water,” according to historian Darrell L. Collins. At the same time, “the horses were covered with icicles and trembling from the cold.”

Averell kept his men moving despite the hardships.

No fires were allowed to dry uniforms or skin. The men understood the reason: This was a race for life. The column, however, was moving at its slowest rate since starting out; nevertheless, by the end of the 18th, the troopers slowly rode into New Castle.

The raiders’ slow rate of movement provided the swifter moving Confederates a better chance to tighten the noose. With Echols in a blocking position at Sweet Springs Mountain, Lee had joined Imboden at Lexington, prepared to convene with Jackson at Covington.

Averell’s scouts, whom he kept out 24 hours a day, had reported the grim news concerning the enemy’s movements. Averell decided that the ride west around Echols and Jones was too rugged. And to fight a pitched battle was out of the question because most of the column’s powder was wet. Averell believed that the only thing to do was to try and sneak between Imboden on the east and Echols and Jones on the west by riding through Covington. The only problem was that the Federal scouts had not discovered Jackson’s force in place in the town.

At 9 pm on the 18th, Averell set the plan in motion by building huge campfires to try and deceive the enemy while the column of raiders rode north into the cold, dark night. Averell had threatened a local with death if he did not agree to lead the troopers along the narrow, winding backroads.

In an additional deception, scouts were sent back toward Salem to give the impression that the Federals had turned back. The ruse worked to perfection. General Jubal Early, convinced the swollen streams had forced the invaders to turn back to seek another route, ordered Lee and Imboden southward, in the opposite direction of Averell’s route. It was a miracle in the making for the Northern raiders.

By noon on the 19th, the Federals had ridden a difficult 30 miles. During the night, exhausted horses with their riders had fallen over logs in the dark forest. Many of the injured horses had to be put to death. Captain Rife remembered, “The awful demand of nature for sleep called loud and unrelenting. A fire,

a warm meal and a bed were worth millions. All around me are men and horses marching, suffering, hungering just as I am. O what had become of the romance of soldiering—the beating drums, marching men, prancing horses and waving flags? That was the poetry of war; this is the bitter reality, robbed of all charm.”

At Covington, Jackson was prepared to destroy the bridges that spanned the Jackson River. Since Averell had discovered that the river was unfordable, he knew the capture of the bridges was critical for the column to continue its escape. Although Jackson had positioned his force in defensive positions, Averell’s scouts located a narrow path leading to Island Ford bridge, a path that Jackson’s men had missed. Averell made plans to attack the bridge immediately because scouts had reported that the Rebel guards were ready to burn the bridge at a moment’s notice.

Within a few hours after sunset, Averell ordered the 8th West Virginia forward. The companies formed in the darkness and slowly rode toward the span. The Southerners, hearing a subdued rumble of a large number of horses’ hooves, suddenly sprang into business. One of the Confederate guards grabbed a torch and sprinted for the bridge. In an instant, shots were exchanged, and “the order to charge pierced the cold night air.” Within seconds, the 8th West Virginia pounded onto the wooden bridge, and it was theirs.

Within minutes, the Yankees were in town trying to find shelter from the numbing cold. Jackson’s men moved in from all directions searching for the invaders, and skirmishes broke out as both sides blundered into short, violent ambushes.

Fearing a strong pursuit, Averell ordered the Island Ford bridge destroyed, as well as bridges on the north side of town, as the column departed. Averell gave these orders knowing that the 14th Pennsylvania had not crossed the Island Ford bridge. Worse yet, Jackson’s men had captured 124 Federal officers and men.

Stranded on the wrong side of the Jackson River, Blakely, commanding the 14th, knew he had to find another way across the icy river. In order to lighten his command, the brigade’s wagons, which were full of rations and tents, and the ambulances were set on fire.

Before elements of the 19th and 20th Virginia Cavalry could trap him against the river, Blakely’s scouts located Holloway’s Ford. Although it was deep, swift, and 120 feet across, it represented the only avenue of escape for the troopers. With Jackson’s men hot on their heels, the 14th Pennsylvania crossed the ice-filled river, but not without losing six men who drowned in the swift current. By midnight on the 20th, Blakely’s men had caught up to the West Virginians. Although many of the men of the 14th felt bitter about being abandoned at Covington, they were happy to be back with the main column.

After another bone-chilling night (now there were no tents, few blankets, and no food), the troopers resumed their march at 4 am. All day long they plodded. Weakness from hunger, exhaustion, and the accompanying mental lapses slowed the advance. By dark, however, the raiders reached the Greenbrier River. In the blackness, many of the men thought they could see the road to Beverly across the river.

Averell decided to begin the final river crossing at 8 in the evening. Huge sheets of ice were flowing down the river. Again, Averell was the first to jump in with his mount and swim to the other side. Then the men, numbed against fear and in a kind of defiance against the frigid water, plunged in after. They all made it across.

On December 21, the Confederates gave up chasing the Federal raiders. By then, Early had become sickened by the whole affair. Rather than waste any more time in pursuit, he decided to concentrate his efforts against Union troops in the Shenandoah Valley.

As Averell’s men moved through Pocahontas County, they began to find food and shelter for the first time in many days. At one farm, the starving men, according to Collins, “eagerly ate all the scraps of rancid fat set aside to make soap.” At another place, the raiders “ate and drank from the swill tub, which contained garbage getting ripe for the hogs.”

On the 22nd, the column rode through Marlin’s Bottom. A few bushwhackers harassed the rear guard, but the raiders barely noticed. Their reduced physical condition forced a nonchalant attitude from many. By now, most of the raiders were walking because their mounts were either dead or smooth shod. Their blackened, frozen feet made riding just about impossible anyway; it was less painful to walk. The majority of the men had to cut their boots off and wrap their bloody feet in rags before hobbling along to continue the march. Actually, the marching probably saved many lives; it helped to heat the men’s bodies.

While the Richmond Examiner ran stories that explained how the Yankee had “made good his escape,” the men of Averell’s Brigade were slipping and sliding as they moved over the frozen land. The column was able to move 22 miles on the 23rd. But that night it was so cold that the officers assigned special details to go around and shake the men awake so they would not freeze. Moreover, much concern derived from seeing the men in a kind of stupefied state. Averell sent scouts ahead to Beverly to gather food and other desperately needed supplies. Most of the men had traveled the last five days without even a scrap of nourishment.

On Christmas Day, a supply train met the suffering column north of Elk. Shouts of joy sounded up and down the column as the men broke into the first food they had tasted for days. By 4 o’clock, the cavalrymen rode, walked, and limped into Beverly.

The men began preparing proper rations. Immediately quartermasters began to issue new uniforms to replace the pieces of blankets or corn-meal sacks many wore. The men ate, thanked God for their survival, and then fell asleep for long periods—the Salem raid was finally over.

Strategically the raid was a success. During the two-week period that it took to repair the damage Averell’s men inflicted on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, Longstreet’s men suffered from short rations. Another benefit of Averell’s raid was the adverse effect it had on General Early’s confidence in the Confederate cavalry. Because Rebel horsemen neither prevented nor trapped Averell’s Brigade, Early’s shattered belief in its ability would sow negative results for Rebel forces during the upcoming Shenandoah Valley campaign.

Oddly, following the raid, Averell’s career declined. His brigade was reorganized and formed into the Fourth Cavalry Division. Then in July 1864, Averell took over the Second Cavalry Division. Achieving only limited success with these commands, Averell was eventually relieved of command by General Philip Sheridan for not conducting a “vigorous” pursuit of the enemy at Fisher’s Hill on September 22, 1864.

Of the units that participated in the raid on Salem, only the 14th Pennsylvania saw any significant action in any campaign in the last two years of the war. Riding with Sheridan, the 14th was a part of the Union victories in the Shenandoah and eastern Virginia. For the remainder of the war, the West Virginia regiments were assigned to guard their home state.

Perhaps the greatest misfortune of the raid was that most of the 124 men captured at Covington were sent to Andersonville, Ga. In the hell of one of the worst prisoner-of-war camps in the South, the men suffered through dread, despair, and for many, death by disease or starvation.

Nevertheless, Averell’s Salem raid was an announcement to the Confederates that Union cavalry was a force to be reckoned with. Gone were the days of Southern cavalier superiority on horseback.

All in all, the Salem raid fit the description of a cavalry raid written by a trooper during the Vicksburg campaign: “A cavalry raid at its best is essentially a game of strategy and speed, with personal violence as an incidental complication. It is played according to more or less definite rules, not inconsistent, indeed, with the players’ killing each other if the game cannot be won in any other way; but it is commonly a strenuous game, rather than a bloody one, intensely exciting….”

Whether or not the men of Averell’s Brigade considered their raid on Salem “exciting” at the time is debatable, but afterward most of them considered it the high-water mark of their military service.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments