By Richard Rule

Leon Degrelle was born in 1906 in Belgium to a prosperous family in the French-speaking region of Wallonia. During the tumultuous years leading up to World War II, he was the Continent’s youngest statesman, but as a soldier on the Eastern Front he became the most famous and highly decorated foreign volunteer in the entire German armed forces. This remarkable man who was a hero to some and a vile traitor to others would earn all stripes from private to general officer and in doing so forge one of the most distinguished careers from among the foreign legions of the Waffen SS.

Leon Degrelle’s Early Years: The Youngest Fascist Statesman in Europe

In the early 1930s, Degrelle, who was an ardent Catholic, had become so disillusioned with the level of government corruption in Belgium that he formed his own Rexist Party, which in essence was a movement of Christian renewal and social justice. Heavily influenced by fascism, Degrelle and his supporters were fiercely anticommunist, anti-Semitic and antibourgeois and quickly capitalized not only on internal ethnic tensions within Belgium but also on the population’s widespread dissatisfaction with the nation’s governing parties.

Charismatic, intelligent, and handsome, Leon Degrelle’s talent for self-promotion coupled with his brilliant oratory skills struck a chord with voters, and his party attracted an incredible 11.5 percent of the vote in the 1936 Belgian elections. It was tantamount to a revolution! At 29 years of age, Degrelle had been catapulted to prominence as the youngest political leader in Europe. His meteoric rise saw British Prime Minister Winston Churchill grant him an audience in London. He visited Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in Rome, and Hitler received him in Berlin.

For two years Degrelle and his party rode the wave of political popularity with gusto, but it did not last. He had attracted many enemies among the political establishment with his bold style, but despite their efforts to undermine him, Degrelle’s personal magnetism saw him reelected to the Belgian parliament in 1938. The Rexists, however, had lost support and fared badly in the polls, and within a few short years the movement would become a marginal political force of little consequence.

The fortunes of his party may have waned, but the volatile Degrelle still had a powerful voice. In the shadows of World War II, he strove to maintain Belgium’s policy of neutrality. Viewing communism as the Continent’s real enemy, he naively discarded much of his suspicion of Hitler’s new Germany and in fact found much to admire. Fascism was certainly popular in parts of Belgium at this time, but Degrelle gradually alienated himself from the wider community with impassioned rhetoric that, while not directly supporting Hitler, often presented the Führer’s actions in a sympathetic light. His failure to comprehend the true and evil nature of the Nazi regime would nearly cost him his life.

Rising to Prominence Under the Nazi Jackboot

War once again came to Europe in 1939. The Phony War, which followed the Wehrmacht’s stunning victory over Poland, ended at dawn on May 10, 1940, with Hitler’s long-awaited offensive in the West. As German panzers steamrolled through the Low Countries, Belgium found itself embroiled in the conflict, and Degrelle was immediately arrested as a Nazi sympathizer and active collaborator. The young statesman was shunted from prison to prison ahead of the advancing German Army and was fortunate to avoid execution. Following France’s capitulation, Degrelle was discovered in the French concentration camp of Vernet by German officials and released.

Despite the harrowing ordeal of imprisonment, a reinvigorated Degrelle returned to Brussels with the firm belief that the occupying Germans would soon grant him substantial political power. He had been arrogantly confident of creating an independent Walloon state in southern Belgium but was frustrated to find that the Nazi authorities doubted his political reliability and had little interest in him or his party.

Following six months of ceaseless but ultimately fruitless maneuvering to gain German acceptance, Degrelle impulsively tried a different tact by making an unequivocally open declaration of pro-Nazi support in January 1941. It worked. With the patronage of the Nazis, the Rexist Party swiftly grew to become the principal francophone collaborationist group in Belgium—and the most powerful. (Get a 360-degree view of the Second World War—from the personal to the political—inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Assembling the Legion Wallonie

With Degrelle’s political star again on the rise, he was ecstatic to learn of the German invasion of Russia in 1941. He quickly declared his unconditional support for the attack, and with rash enthusiasm offered to raise a volunteer battalion of his fellow French-speaking Walloons to join the fight against Bolshevism. Degrelle was convinced that such a military commitment would ensure a place of honor for Belgium in Hitler’s vaguely defined “new order” for Europe. He was surprised, however, when many Rexists balked at fighting alongside the Germans and was even further dismayed to learn that the German military authorities in Belgium were less than enthusiastic about having inexperienced foreigners in the German Army. Perhaps in light of the propaganda value of such a unit or through pressure from higher authorities in Berlin, the Germans eventually granted Degrelle permission to raise a unit comprised only of Belgian volunteers. The unit, christened the Corps Franc Wallonie or Legion Wallonie, was to become a reality.

As the Wehrmacht tore across the Soviet Union at breakneck speed, Degrelle was chafing at the bit to get his unit on the ground in Russia to join the last battles prior to the German victory parade in Moscow—which seemed only a matter of weeks away. Details were yet to be ironed out in regard to uniforms, oath of loyalty, and many other issues, but Degrelle was already hard at work touring Belgium in search of legionnaire volunteers. With all his usual speech-making skill, he appealed to the adolescent fervor of the times by announcing that the youth of Belgium were now poised to join the most glorious military campaign in world history.

Despite German propaganda and Degrelle’s postwar writings boasting of the masses that flocked to join up, the reality was that very few other than Rexist Party members volunteered for service. Perhaps not surprisingly, most Belgians were horrified that Degrelle could contemplate wearing the military uniform of a conquering foreign power and completely ignored his call to arms.

Faced with an embarrassing and very public shortfall in numbers, Degrelle needed to shore up support for the Legion. In a desperate move, he shelved plans to pursue his political career and announced on July 20, 1941, that he himself would volunteer for active service. Degrelle, now 35 years old, had never even fired a gun, but this dramatic gesture proved to be the turning point in the recruiting drive. Within days several hundred previously undecided Rexists followed the example set by their leader and signed on.

On the appointed date of departure, August 8, 1941, Degrelle and 849 other predominantly working-class volunteers assembled in the Place Royale in Brussels. The large crowd that gathered to see the recruits depart for basic training in East Prussia was viewed by Degrelle as a sign of Belgian support. His detractors claimed the crowd was filled mostly with family members, Rexists, or curious but unsympathetic onlookers.

Addressing his compatriots from beneath an enormous photograph of Adolf Hitler, Degrelle was at pains to dismiss the charges of treason being heaped upon them. He instead described the volunteers as “true patriots” who were ensuring a place of honor for the nation in the New Europe being forged in blood on the Eastern Front. While there is no doubt that Degrelle believed this to be the truth, neither the power of his oratory nor the eloquence of his words swayed many Belgians. Most viewed him as a mouthpiece for Nazi propaganda and regarded the forming of the Legion to fight for the Germans as an inexcusable act of betrayal. For reasons of idealism or self-interest, or both, Degrelle had eagerly taken up the poison chalice of political collaboration with both hands and drunk deeply. His fate, and the fate of those who followed him, was now irreconcilably manacled to that of the Third Reich. Most would not realize the lethal consequences of their actions until it was much too late.

Assigned to Army Group South

As the 850 men of the Corps Franc Wallonie marched off in the fine, misty rain of that August morning in 1941, few would have believed that within four years all but three would be devoured in the blood-drenched maws of the Eastern Front. By the time basic training had been completed in early November 1941, the number of volunteers within the Legion had swollen to 1,500. Placed under the command of a retired Belgian colonial officer, the unit was dispatched by rail to the rolling wheat lands of the Ukraine in the southern sector of the Russian Front.

The wholesale destruction and endless columns of Russian prisoners they had passed en route gave every indication that the invincible armies of the Reich were on the verge of a resounding victory. The volunteers were not to know that the exhausted German spearheads operating along a vast front were in fact slowing down, blunted by hardening resistance, overextended supply lines, and autumn rains that had turned the battlefield into a sea of mud. There was, however, still great optimism among the Belgians that the war would be won before the onset of winter.

Upon arriving at the front, the Legion was incorporated into Army Group South and allotted the replacement battalion identity of 373 (Wallonische) Infantrie Battaillone.

Degrelle and his comrades saw themselves as a continuation of the Belgian Army but were shocked to realize that the German military, already skeptical about the volunteers’ reasons for fighting, had little regard for their capabilities. Dismissed as being merely a propaganda unit, the battalion was assigned to the rear areas to undertake antipartisan operations.

Why Degrelle Was Dubbed “Modest the First, Duke of Burgundy”

Upon enlisting, Degrelle’s request for a commission had been denied by the German authorities due to his obvious lack of military experience, but to the surprise of many, Leon Degrelle had adapted to military life as a humble private with ease. This bon vivant made an implausible soldier, but he endured the hardships of the simple infantrymen without complaint and was good naturedly dubbed “Modest the First, Duke of Burgundy.” During this unpalatable antipartisan phase of his service, Degrelle showed himself to be a courageous, inspirational soldier with a natural ability to lead men in combat.

Unlike many European collaborationist leaders who merely toured the front for propaganda, Degrelle actively participated in the fighting that occurred against the Russian guerrillas. The irregular partisan enemy with whom they were engaged adhered to no set order of battle or military doctrine, and the hit-and-run tactics they employed were difficult to counter or anticipate. The untried soldiers were thrown into an extraordinarily cruel type of warfare that often required them to shoot down women and children who were fighting alongside the men. These antipartisan duties, characterized by a ruthless barbarity considered too grisly for military journalists to report, was not the war the Belgians had envisaged or signed up for. The sobering fact was that there were no glorious battles, just endless terrifying skirmishes through forests and swamps.

Exposure to the terrifying brutalities of the front line with all its sickening horror, death, and sorrow had shaken the Belgians to the core. The shock of infantry warfare had been worse than any of the Walloons could have imagined, but their plight deteriorated further with the onset of the worst Russian winter in 150 years.

The combination of the marrow-chilling Russian winter, horrific casualties, and constant ridicule from their German counterparts saw the mood among the ill-prepared and ill-equipped Belgians shift between outright mutiny and abject despair. As temperatures plunged to 42 degrees below zero, Degrelle tried to lift their demoralized spirits, but he could see that the future for the Legion as a fighting force appeared bleak. Degrelle was not a military strategist, but as the weeks passed he realized that Germany was not going to win the war in the East as quickly as he had first thought.

In fact, it seemed likely that there would be many long, agonizing months of hard fighting through blizzards, snow and subzero temperatures before there were any German victory parades through Red Square. As reports filtered through of the Wehrmacht’s failure at the gates of Moscow in December 1941, he, like most around the world, had yet to grasp that this was the beginning of the end for the Third Reich. Looking beyond his own grim circumstances, he may well have sensed that the crusade he so enthusiastically embraced for himself and his fellow volunteers had soured. Most of the despairing men around him were convinced they were all going to die an agonizing death in the snow.

The Walloons’ Baptism of Fire

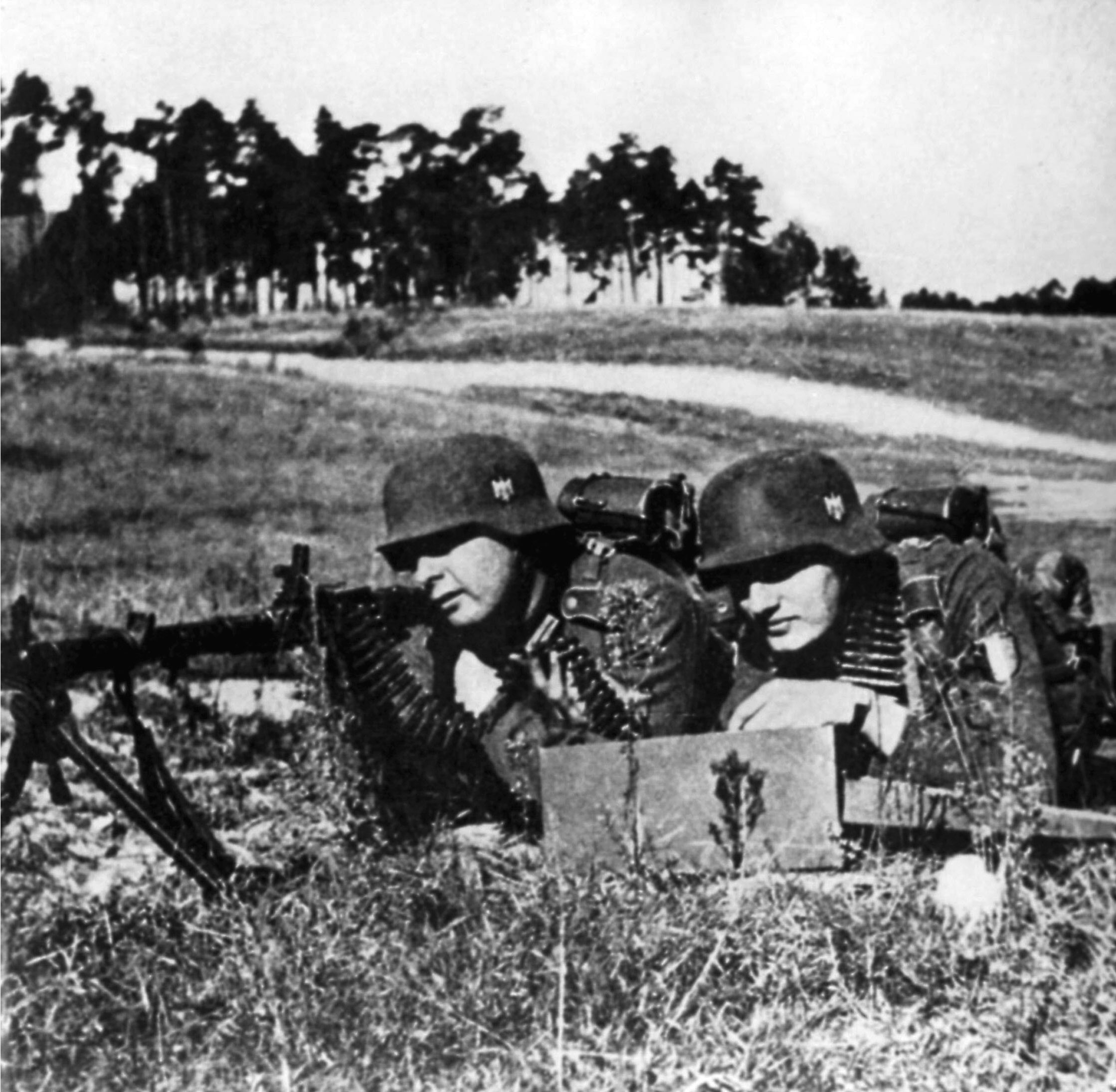

By February 1942, the German position in Russia was still precarious. The Wehrmacht had been driven back over 150 miles from Moscow, and the Russians attempted to vigorously exploit their success with a further breakthrough in the Donets Basin. This bitter struggle provided the scarcely blooded Walloons with their first taste of real combat in fierce defensive battles for the villages of Rosa Luxembourg and Gromovaya-Balka, which lay in the path of the Soviet offensive. Against overwhelming Russian forces, the heavily outnumbered Walloons showed remarkable combat prowess, courage, and grim determination fighting alongside Waffen SS troops in the seesawing battle to ultimately hold the villages. Among those decorated was Degrelle himself, who was awarded the Iron Cross for his bravery and inspirational leadership during savage hand-to-hand combat.

This baptism of fire against Red Army troops came at a horrendous cost for the Legion. A third of its men and almost all of its officers had been killed or wounded. Despite the grievous losses, the fighting qualities and astonishing tenacity displayed by the Belgians finally earned them the admiration and respect of Wehrmacht troops. With the Walloons’ reputation greatly enhanced, the thawing of relations with their German counterparts restored flagging morale, as did their considerable successes in the savage battles that awaited them during the autumn of 1942.

In time, even the Russians came to know of these Belgians and would often broadcast in French asking the volunteers to come over and fight for Free French leader Charles de Gaulle.

The steady loss of officers and NCOs had contributed to rapid promotion for Degrelle, and by May 1942 he was finally commissioned as a lieutenant. At this time the Legion was placed under the command of SS Obergruppenführer (Lieutenant General) Felix Steiner’s famed SS Division Wiking in preparation for an attack aimed at regaining the territory lost the previous December. On June 28, 1942, the Wehrmacht launched its massive summer offensive in the Caucasus, which, having caught the Russians completely off guard, soon had them fleeing in headlong retreat. With the Germans having regained the military initiative, Degrelle was convinced that this was the beginning of the final drive to victory.

With numbing fatigue their constant companion, the Walloons pushed ahead in stifling heat through countryside that had long since shaken off the white blanket of winter. Degrelle, whose tunic was now adorned with the Iron Cross both First and Second Class, drove himself and his men hard to stay in contact with the Soviet forces. Most of the enemy troops they saw, however, had already fallen victim to marauding Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers, and thousands of their loathsome corpses lined the roadsides baking in the sun. There was no time to bury them. With a sense of pride, the volunteers of the Legion strove forward day after day, week after week, not giving the enemy a moment’s respite.

Fighting alongside the highly motivated Dutch SS troops of the Wiking Division had been a revelation for Degrelle. He was impressed with the spirit, ethos, and material conditions of these elite soldiers and decided that the future of the Legion would be better served within the ranks of the increasingly powerful Waffen SS.

Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler had already cast his covetous gaze over the now battle-proven Walloons, and, like Degrelle, considered them worthy of admission into his private army. The two men shared a common goal but seemingly little else. Degrelle did not trust Himmler, and the latter in reality saw Degrelle as little more than a convenient propaganda tool for winning over foreign recruits.

Nonetheless, the move to the SS was a popular decision among the officers and men of the Legion. Degrelle also believed his postwar future would be greatly enhanced in the SS. The personal prestige of having his Legion recognized as an elite military formation would carry a great deal of weight with the decision-making hierarchy of the Reich after the war.

A Crushing Loss in the Korsun-Cherkassy Pocket

In the spring of 1943, the Legion, boosted by an influx of new recruits, was transformed into the 5th SS Freiwilligen Sturmbrigade Wallonien with SS Hauptstürmfuhrer (Captain) Leon Degrelle as its chief of staff. Elevated to new heights of combat prowess, the 2,000 men of the fully motorized brigade were rushed to the middle Dneiper sector of the Ukraine in November 1943. With the runic SS symbol now adorning their collars, they were once again deployed alongside the SS Wiking Division as part of two German corps occupying a salient extending into the Soviet lines west of Cherkassy. A Russian offensive west of the Dnieper was soon massing around the salient, clearly revealing Soviet intentions to surround and destroy the German forces inside. Despite warnings from his generals, Hitler doggedly refused to allow a strategic withdrawal.

German troops desperately tried to keep an escape route open, but powerful Russian armor sealed the ring around the Kessel, or Cauldron, on January 28, 1944. Soon, the noose was tightening. More than 50,000 Axis troops were faced with complete annihilation, a fact eagerly anticipated by Degrelle’s enemies at home and abroad. An armored relief force of the III SS Panzer Corps soon began battering its way through the Soviet ring from the southwest to link up with the besieged troops. The Walloniens and the Wiking Division, meanwhile, were given the unenviable task of defending against the Russian attacks at the extreme eastern corner of the shrinking pocket, while the bulk of the German forces prepared to break out to the west. In the face of furious Red Army assaults, the tenacious Walloniens held firm through 17 torturous days and nights of ferocious close combat.

During the bloody engagement, the brigade commander was killed, and it fell to Degrelle to quickly take command of what was left of the shattered unit. Degrelle’s questionable grasp of military strategy was compensated for by his unflinching courage, cool head, and hard-won battle experience. At a time when the fate of the Walloniens hung by a thread, it was often Degrelle’s qualities as a fighting leader that set the example for his men. Few of his troops would ever forget seeing Degrelle, in agony from a deep wound in his side, continue to personally lead them through fighting so ghastly that it was considered completely beyond the comprehension of anyone who had not lived through it.

Despite the hellish conditions, the Belgians not only managed to hold the Russians but eventually broke out of the trap themselves. Dragging their wounded with them, they fought alongside German units in a desperate rear-guard action through lethal Russian rocket and artillery fire. However, as Degrelle and the exhausted remnants of the brigade closed on the German lines, they appeared certain to be overtaken and massacred by the pursuing Russians. In a heroic act of self-sacrifice, Wiking’s few remaining panzers suddenly turned back to hold off the Red Army units until the Belgians had reached safety.

Degrelle had survived another close encounter, but the heroic stand in the Cherkassy Pocket had come at an appalling cost. Not only had all the Belgians’ heavy equipment been lost, but of the original 2,000 men that began the siege, 1,300 had been left dead on the battlefield. In reality, the brigade had been ground to pieces. Still reeling from the effects of heavy combat, Degrelle was confirmed as the brigade commander and promoted to SS Sturmbannführer (Major). For his incredible bravery, he was flown out of Russia to be awarded the Knights Cross by Hitler, and as the two men went over the battle on a large map it was obvious that Hitler not only had a great personal interest in the progress of the brigade but also held Degrelle in high esteem.

Degrelle’s Brief Return to Belgium

With the German propaganda machine eager to promote the exploits of Degrelle to assist foreign recruiting, he returned to Brussels with approximately 160 survivors of the battle to receive the largest mass welcome in Belgian history. Thousands of Belgians lined the streets and boulevards of the capital to cheer the returning Degrelle as he rode in a tank accompanied by his children. Lavish receptions were held in his honor, and with all his customary skill and verve he delivered an impressive speech to more than 10,000 people in the Brussels Sports Stadium. The publicity surrounding Degrelle, however, failed to impress many veterans of the other largely ignored Belgian units who had also fought their way out of the Cherkassy Pocket. They would caustically remark that they too had paid a heavy price in the battle but did not have Degrelle, with his indefatigable talent for self-promotion, to recount their exploits.

By this stage of the war, Degrelle seemed to have little interest in the day-to-day affairs of the Rexist Party in Belgium. He even contemplated dissolving the party altogether to focus his energy on fighting the war. Degrelle toured German factories and prisoner of war camps recruiting for the brigade and spent time consolidating his prestige and stature with Nazi power brokers. Through an energetic combination of bluster, charm, and intrigue he fostered strong ties with key functionaries within the SS. He was highly regarded, but his efforts were slowly being undermined by Germany’s looming defeat.

The Reich’s military reversals in other theaters washed over Degrelle, but in February 1944, the massive Soviet offensive aimed at driving the Germans out of Estonia was not so easily ignored. With the force of a sledgehammer, Red Army units swamped the exhausted German forces of Army Group North, which included the volunteer SS formations of Steiner’s III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps. By May, following months of fierce and bitter fighting, the battle raged around the vital town of Narva near the Estonian border with Russia, but at that time Degrelle’s shattered brigade was in Poland for badly needed rest and reorganization.

With the Estonian sector of the front buckling under Soviet pressure, the Germans needed men to fill the gaps in the line. Degrelle was in Belgium on leave for his brother’s funeral when informed that the Germans had rushed 300 barely trained Wallonien recruits and 140 other troops from Poland to Estonia. Their instructors went with them to conduct further training during the deployment. The situation was so critical that the bewildered Belgian recruits were immediately thrown into the line near Dorpat to hold a Russian breakthrough. Most did not even know how to use their weapons.

Degrelle was absolutely furious that his recruits had been sent to the front. Defying Hitler’s orders that he not return to the fighting, he immediately left for Estonia in search of the 440-man battalion. Degrelle and his men quickly found themselves deployed to meet the threat of a Soviet breakthrough at Pskov.

The Walloons’ Plummeting Morale and Recruitment

The situation in Estonia was chaotic as the line seemed ready to crumble under the hammer blows of Soviet armor and air strikes. The Russians were streaming through the region like a tidal wave. Using a French-speaking German officer to translate, Degrelle rallied panicked German troops in his sector. He grabbed others by the scruff of the neck and forced them back into the line. Degrelle knew how to fight the Russians, and standing completely exposed to the enemy he commanded an ad hoc force with incredible vigor, skill, and courage until the crisis had passed and the Russians were driven back.

In a remarkable feat of arms, Steiner’s SS Panzer Corps ultimately held firm against vastly superior Russian numbers but had been bled white in the process. For three weeks during the Battle of Narva, Degrelle’s mostly inexperienced Walloniens had been committed to heavy combat. Only 32 of the original 300 recruits survived to rejoin the brigade.

For his extraordinary courage and leadership on the Narva front, Degrelle was flown out of Estonia and once again brought before Hitler on August 27, 1944. He had the unique distinction of being one of the few nonethnic Germans to be awarded the coveted Oak Leaves to the Knights Cross along with the prestigious Close Combat Clasp in gold, awarded to men who had fought more than 50 days of close- quarter combat. Degrelle was a clear favorite of the German leader, and after an hour of conversation, Hitler took the Belgian’s hand in both of his. “If I had a son,” he said slowly,” I would want him to be like you.” Hitler then left, and they would never meet again.

Despite being virtually annihilated during its service in Russia and Estonia, the Wallonien Brigade was to be upgraded in September 1944 to form the 28th SS Division, commanded by SS Oberstürmbannfuhrer (Lieutenant Colonel) Leon Degrelle. New recruits were drawn from Belgians hoping to avoid labor service in Germany, Spanish veterans, Frenchmen, and criminals taken directly from Belgian and German prisons. Their numbers, however, would not meet the division’s manpower needs, so a massive recruiting drive was launched to bring the division up to strength. The age limit for recruits was lowered, and the upper limit raised in an attempt to find more sorely needed men.

Following the successful Allied landings on D-Day, the appeal of joining an elite unit had soured as Germany’s military fortunes plummeted. The Legion rarely rejected anybody by this stage of the war, and many of the conscripts who were dragooned into the 28th SS Division Wallonia were generally of very poor quality. A sizeable number deserted at the first opportunity. Already severely hampered by a shortage of experienced officers and NCOs, the actual strength of Degrelle’s command was barely 8,000 troops. Of these, only half had any military training. It was in reality a division on paper only and would reenter battle as little more than a reinforced brigade.

With Germany’s armies retreating on all fronts, Degrelle clung grimly to his division and the troops he led. There was nothing beyond that. In front, he faced the all-conquering Red Army. Behind him lay a shattered political dream as the Rexist Party he had formed began crumbling to dust. With the Western Allies fast approaching Brussels, many high-ranking Rexists who had diligently aided the Nazis deserted their posts and tried to melt away to avoid reprisals.

Degrelle’s shaken morale was lifted by the ambitious German offensive in the Ardennes in December 1944, which resulted in the Battle of the Bulge. By Christmas, however, the attack had ground to a halt and then collapsed with more than 80,000 casualties. In the wake of Hitler’s disastrous gamble in Belgium, Degrelle’s wavering belief in an improbable Nazi victory was only kept alive by rumors that wonder weapons would soon turn the tide. Like so many others, Degrelle seemed to have closed his eyes to the reality that the war was irrevocably lost. Only catastrophic defeat and the dispensation of hard justice awaited them all—particularly willing foreign servants of the Reich.

The Precipitous Decline of the Third Reich

In late January 1945, Degrelle and his Walloons joined many other pitifully understrength SS units of Steiner’s 11th SS Panzer Army for the ill-fated Stargard counteroffensive in Pomerania. The autobahn from Berlin to Stettin, along which the Walloons traveled to the assembly area, was congested with thousands of people desperately fleeing from the Russians. Powerless to help them, Degrelle impassively surveyed the pitiful columns of gaunt refugees with no illusions about their fate if and when the approaching Red Army caught up with them. Stories of wholesale Russian atrocities against civilians in East Prussia were already spreading like wildfire.

Launched with all the customary élan and ferocity typical of the Waffen SS, the offensive soon stalled and ultimately accomplished little other than to precipitate a powerful Soviet counteroffensive. Degrelle once again led from the front as his Walloniens fought fanatically in the face of overpowering Soviet forces. They were doggedly forced back through central Pomerania toward Berlin. By mid-March 1945, following weeks of unrelenting combat in the hopelessly one-sided fight, Degrelle’s division had been burned to a cinder.

As ruinous destruction loomed like some ghastly specter at the gates of the German capital, Degrelle saw ample evidence of the German Army’s total collapse. The stiff, lifeless bodies of countless Wehrmacht and Volkssturm soldiers, suspected of desertion, had been left hanging by the roadside from trees, lamp posts, and makeshift gallows as a gruesome warning to others. Placards pinned to their uniforms or hanging around their necks typically read, “I hang here because I left my unit without permission.”

In spite of the draconian measures being employed by the SS, Degrelle decided to release those volunteers who no longer wished to fight. They were free to make their way home to Belgium or elsewhere. Others were given foreign worker cards and disguised as conscripted laborers. From the remaining 650 officers and men, he formed one well-equipped battalion to continue the futile struggle. Even though Hitler was dead, the remaining Walloons knew that as foreign volunteers they had no future beyond the life of the Reich. Their fate was sealed. With the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads, many saw death in combat as the only course open to them, and they were determined to fight to the bitter end.

Scenes of panic, death, and cruelty typified the Reich’s rapid disintegration, but a surprising number of German officers at this time were convinced that if they could hold on the advancing Western Allies would soon join with them to fight the Soviets. Degrelle saw such hopes as delusional. They were all living on borrowed time, and even his unconfirmed promotion to SS Brigadeführer (Brigadier General) on May 2, 1945, held little real meaning.

Leon Degrelle’s Escape to Spain

With the final surrender of Berlin in May 1945, Degrelle was desperate to avoid Russian captivity and ordered as many of his worn-out veterans as possible to make for the Baltic port of Lubeck to surrender to the British. The man the Belgian authorities really wanted, however, would not be among them. Degrelle, who had little doubt about the fate that awaited him in his native land, had fled north through Denmark and Norway to Oslo, where he commandeered a plane and took off for the sanctuary of Spain. After a daring 1,500-mile flight over portions of Allied-occupied Europe, he crash-landed on the beach at San Sebastian in northern Spain but was gravely wounded and hospitalized for over a year.

The Belgian government was soon demanding his extradition for treason, but Spain’s leader, General Francisco Franco, refused to hand him over. Degrelle’s family and supporters in Belgium were not so fortunate. Many were arrested and tortured. Most of the Walloon soldiers who had surrendered to the British had been handed over to Belgian authorities and thrown into prison or condemned to death. Degrelle’s eight young children (seven girls and a boy) were separated and placed in detention camps in different parts of Europe, where their names were changed to frustrate any chance of reuniting them. Not only did the Belgian authorities order these children never be allowed contact with each other or their father, but they also passed a law, the Lex Degrellana, which made it illegal to transfer, possess or receive any book by or about Degrelle. His subsequent work, Campaign in Russia, was banned in Belgium.

In 1947, most of the Rexist leadership was subjected to trials in Belgium, and 25 were executed. Degrelle was condemned to death in absentia. Knowing that many in the postwar Belgian government had been wholehearted collaborators themselves, Degrelle challenged the establishment on 12 separate occasions during his 50-year exile to put him on trial in a legitimate court of law. His demands were ignored.

Isolated in Spain, branded a Nazis fugitive, and demonized in his homeland, Degrelle rose to mythical status among many neofascist groups and nostalgic admirers. Protected and sheltered by powerful Spanish friends, he eventually forged a new life as founding head of a major construction company in Madrid, which ironically procured contracts with the U.S. government to build military airfields in Spain. Meanwhile, friends scoured Europe for his children. In time, all were found and spirited to Spain.

An Unapologetic Fascist to the End

Beyond reach of the Belgian authorities, Degrelle remained unapologetic about his fascist views or associations and became a prodigious writer and speaker. His controversial far- right solutions, Holocaust denial, and self-published revisionist views regarding Hitler and the Nazi genocide led to widespread resentment and anger. Following legal action, the Supreme Court of Spain actually imposed a substantial fine on Degrelle for bringing offense to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust, but he continued undeterred. Conveniently overlooking the deplorable conduct of the SS in the occupied territories, Degrelle still embraced many of the tenets of Nazi ideology and his belief that Hitler was the greatest statesman of his time. He also appeared to have no regrets about his collaboration or his place in history other than to tell Dutch television, “If I had the chance, I would do it all again, but much more forcefully.”

After decades living comfortably in Spain, Leon Degrelle died from cardiac arrest in 1994 at the age of 87. Many young Belgians barely knew of him, but the Belgian government had never forgotten or forgiven his collaboration or military service with the Nazis. He was refused burial in Belgium, and the government took steps to prevent Belgian veterans who had fought alongside Degrelle from attending his funeral in Spain.

Today, there is little acknowledgment for the thousands of Belgians who died fighting on the Eastern Front; their sacrifice and distinguished combat reputation remain largely ignored. Leon Degrelle, however, spent his life arguing that they had volunteered for service with the Germans through a fierce desire to save Europe from Bolshevism. The crimes attributed to the Waffen SS, he said, were as often as not in retaliation for even worse atrocities committed by Red Army units. During the postwar years, few were willing to listen or accept comparisons.

Whether his true motivation to fight for Hitler was to bring about the destruction of communism is debatable; many still firmly believe Degrelle had created the Legion purely to further his own political aspirations. Whatever the truth, the charge of treason that stained Degrelle’s military career in no way diminished his record as a combat commander who regularly led from the front—a place where true leaders are sometimes hard to find.

Australian author Richard Rule is a frequent contributor to World War II History. He resides in Melbourne.

This was a truly remarkable man. Irrespective of what one may think of him, nobody can slight his qualities, resourceful bravery and intellect, regardless of the aspects to which they were applied.

Strange how a government of Nazi collaborators and Congolese butcher’s of rubber workers limbs, can accuse a individual of doing something that they did themselves. A disgraceful act of vengeance to separate and scatter innocent children around Europe. What Crimes did they commit?

Your point is well taken.

I don’t know anybody in any politics that would volunteer to go into real battles where their own lives are in jeopardy…I have much Respect for this Man…being in such Battles myself…

DeGrelle was a first-rate hero. Courage has no allegiance. His detractors are , to a person, not worthy to wash his socks.

There are many people that fought for bad causes. That DeGrelle continued to support Nazis will forever stain his reputation. That cannot be overlooked or ignored. His denials of the Holocaust alone condemn him.