By Arnold Blumberg

Word spread like wildfire through the camps of the Army of the Potomac during the second week of November 1862: “Little Mac” was out, “Old Burn” was in. Nestled in numerous bivouacs situated from Snicker’s Gap to Warrenton, Virginia, the bombshell news was received by the troops with disbelief and despair, followed by indignation. To many of the officers and enlisted members of the army it was incomprehensible that the beloved organizer and leader of the Federal government’s premier field force, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, was being replaced by the genial but less than charismatic Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. The able brigadier of the Iron Brigade, John Gibbon, spoke for many in the army when he postulated that booting McClellan proved “that the Government has gone mad.”

“Old Burn” Leads the Army of the Potomac

Some men are born to greatness, others have greatness thrust upon them; Ambrose Burnside was neither. Born on May 23, 1824, in Liberty, Indiana, the fourth of nine children, Burnside grew into an imposing six-footer with a large head topped with thin brown hair. After graduating 18th of 38 in the class of 1847 from the United States Military Academy at West Point, he was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the 3rd United States Artillery Regiment. Service in the Mexican War was followed by a posting in New Mexico Territory. In 1853, Burnside resigned from the army and moved to Rhode Island to manufacturer a breech-loading carbine of his own design. Failing to sell his weapon system to the army, he took a job as a cashier with a railroad company.

As a graduate of West Point, Burnside rapidly rose from regimental to brigade to corps command during the first two years of the Civil War. His most distinguished achievement was his able handling of an amphibious operation along the North Carolina coast in 1862 against a greatly inferior enemy force. His reward was promotion to major general and an offer from President Abraham Lincoln, after the failure of McClellan’s mismanaged Peninsula campaign, to command the Army of the Potomac. Burnside turned down the offer, explaining that he was not up to such an important task. Nevertheless, even after his uninspired performance at the Battle of Antietam, the government prodded him to take charge of the main Union Army in the East. This time the general, known mostly for the massive sideburns that curved around his lips into a full mustache, reluctantly accepted the post.

The choice of the transplanted Rhode Islander was puzzling to many since he clearly did not feel competent to hold the job. Nothing in Burnside’s prior service had demonstrated strategic genius or originality. But given his senior rank and the fact that the North’s leading politicians had no strong objections to his appointment, “Old Burn” got the top spot almost by default.

Burnside’s Weak Division Leaders

Burnside realized that the government wanted a rapid march on Richmond. As a result, his army would not be allowed to go into winter quarters, as was normal in November. He formulated a plan and sent it to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, general in chief of the Union Army, on November 9, the same day that he took over command of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside advised Halleck that he would take the most direct route to Richmond by moving from Warrenton to Fredericksburg, Virginia, crossing the Rappahannock River near Falmouth and heading straight for the Confederate capital 50 miles farther south. Simultaneous with the advance of the main army, feints would be carried out in the direction of Gordonsville and Culpeper Court House, in the hopes of confusing the enemy as to the real objective of the Union campaign.

On November 14, Burnside received the go-ahead from the president to put his plan into action. Appended to the approval was the cautionary injunction that in Lincoln’s view the scheme would only succeed “if you move rapidly; otherwise not.”

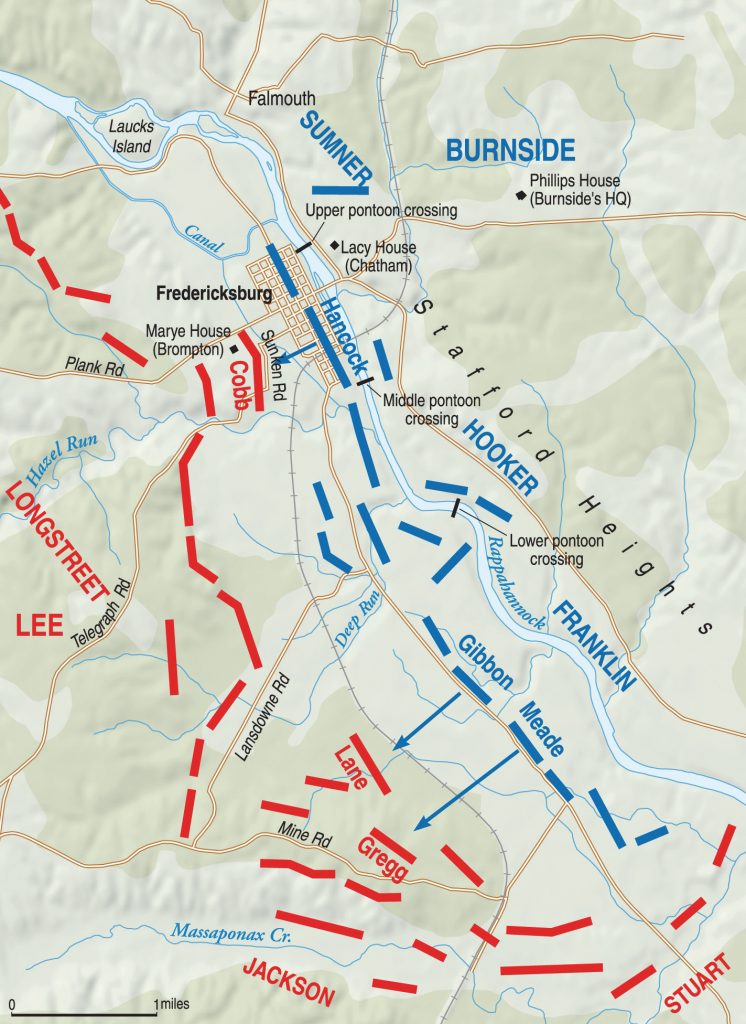

With the final approval in his pocket, Burnside prepared to go forward. He organized his forces into three grand divisions: the Right Grand Division (II and IX Corps) under Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner; the Left Grand Division (I and VI Corps) under Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, and the Center Grand Division (III and V Corps) under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. XI Corps, under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, was designated as reserve. Cavalry and artillery units were scattered among the grand divisions. The new setup made controlling the army more difficult in battle because it placed an additional layer of command that would interfere with communications at critical times between the army leader and his subordinate commanders.

Burnside’s division leaders were another weakness. They were, on the whole, a mediocre bunch when it came to military capability. Sumner, although brave in combat, was slow to move and needed constant supervision. Franklin was a good enough engineer and administrator, but no ball of fire on the battlefield. Hooker, the most aggressive of the group as well as a born leader of men, was highly unhappy with Burnside as the leader of the army.

Marching on Fredericksburg

On November 15, the 112,000-man Army of the Potomac began its journey from Warrenton to Fredericksburg. The countryside was mostly forested, with rough, open fields dissected by narrow country lanes whose condition was made worse by fall rains that continued to come down during the march. Slowing the army further were the thousands of cumbersome wagons pulled by horses and mules that made up the army’s supply trains. Poor roads, mud, and the high attrition rate of the animals assured that the wagon trains could not keep up with the infantry, who frequently found themselves blocked by the masses of horse-drawn vehicles. Despite the obstacles, however, the trek to Fredericksburg averaged a respectable 15 miles a day.

As the Federals advanced in two main columns southeast from Warrenton, Robert E. Lee had only the slightest inkling of Burnside’s intentions. While the Federals made their way toward Fredericksburg, only 35 miles from their starting point, Lee’s army was badly divided. Thirty miles to the west at Culpeper Court House was Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s 41,000-man I Corps. In the Shenandoah Valley, 75 miles northwest of Fredericksburg at Winchester, stood Lt. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s 38,000-strong II Corps. Maj. Gen. James E.B. Stuart’s 6,000 cavalrymen screened the countryside along the Rappahannock River. In the event of an enemy attack, Lee would have to unite his forces quickly—a daunting task even for the fast-moving Confederates.

On the 17th, Lee was informed about Sumner’s initial move toward Fredericksburg. In response, he ordered two of Longstreet’s infantry divisions, under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom, Jr., to head immediately for the threatened city. By the 20th, he was sure of Burnside’s destination and ordered the rest of his I Corps units (the infantry of Richard A. Anderson, George E. Pickett, and John B. Hood) to move swiftly to that location.

As November 23 dawned, nearly 40,000 Confederates were concentrated in the Fredericksburg vicinity. Without the presence of Jackson and his troops, Lee had not decided whether to fight or withdraw. He still held out the option of retreating to the North Anna River, where he could take a strong defensive position and then seek an opportunity to launch a counterattack. He decided to wait for the enemy’s next move and the arrival of Jackson before making up his mind about which course to pursue.

The Campaign’s Delay

By then, Sumner’s divisions had reached the town of Falmouth, just three miles north of Fredericksburg on the north shore of the Rappahannock. After Burnside arrived, Sumner requested permission to cross the river and occupy Fredericksburg, which appeared to be empty of Southern forces. Burnside, fearful that Sumner’s men might become trapped south of the river by rising water, denied the old officer’s plea for action. He reasoned that it would be safer to wait for his pontoon train (which was expected to arrive at any time) to ensure a safe crossing and secure communications north of the river. In retrospect, Burnside’s decision not to cross immediately was a mistake. The town was still empty of any Confederate troops, and its seizure would have permitted Federal artillery to be stationed on Stafford Heights, just across the river, to safeguard the crossing.

Burnside’s entire plan of campaign hinged on the timely arrival of his pontoon train at Fredericksburg. What he did not know was that the train had bogged down completely. A series of poorly written orders, little initiative or understanding by junior officers of the importance of the boats in the campaign, and lack of needed parts prevented the pontoon train from reaching Falmouth until November 27, even though the original order had been drafted on November 6. The critical delay in the arrival of his pontoons added to uncertainty about the whereabouts of Jackson’s corps convinced Burnside not to storm across the river at once.

While the Army of the Potomac dithered on the north bank of the Rappahannock, Lee ordered Jackson to transfer his force from the Shenandoah Valley to Fredericksburg. Starting on November 21, Jackson’s “foot cavalry” marched 175 miles in 12 days to reach the rest of the army. With the two armies now facing each other across the Rappahannock River, Lee was mystified by his opponent’s inaction. “What the designs of the enemy are I do not know,” he said. While Lee tried to decipher the enemies’ plans, both sides built winter quarters and suffered alike from cold weather, shortage of supplies, and boredom.

Crossing the Rappahannock

Pressure on Burnside to reignite his campaign continued coming from the Northern press, politicians, his own officers, and even President Lincoln himself. Looking for a way to strike a blow before the full impact of winter halted all military operations, the general considered storming the enemy positions 12 miles downriver from Fredericksburg but scrapped the plan because of the difficulty of achieving the element of surprise while moving the needed number of men and supplies to the point of attack. Meanwhile, the Confederate Army continued preparing defensive positions behind Fredericksburg. Longstreet’s corps took up positions at Taylor’s Farm, opposite Beck’s Island in the Rappahannock, and along the high ground south of town. On the Lansdowne Valley Road, Longstreet’s columns linked up with Jackson’s corps. Jackson stretched his divisions along the Military Road to Hamilton’s Crossing. Stuart’s cavalry was posted on Jackson’s right to guard the flank and keep watch on the road to Port Royal.

The morning of December 11 saw the temperature stand at a frigid 25 degrees, with dense fog hanging over the area. The Federals planned to cross the 400-foot-wide river that morning by constructing pontoon bridges at three points along a two-mile stretch. The northernmost point would be the site of two parallel pontoon bridges comprising the Upper Bridge, just to the north of Fredericksburg. The 50th New York Engineer Regiment was assigned this task. The second bridge, known as the Middle Bridge, was built by the 15th New York Engineer Regiment. It stood about one mile south of the Upper Bridge and connected with the southern fringe of the town. The southernmost structure, the Lower Bridge, was located a mile south of the Middle Bridge and a quarter of a mile south of Deep Run.

Sumner’s Right Grand Division would cross at the Upper Bridge, Hooker’s Center Grand Division at the middle span, while Franklin’s Left Grand Division debouched from the Lower Bridge. Supporting the crossing were 183 cannons under Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt. These guns were placed on the 30- to 50-foot-high bluffs known as Stafford Heights, which ran along the Federal side of the river for five miles. The artillery had three missions: drive the entrenched Confederates from the hills west of town, prevent enemy forces from massing on the plains opposite the Lower Bridge, and suppress enemy opposition to the bridge building and subsequent movement of friendly forces across the river.

Upper and Middle Bridges Contested

Around 6 am, all the bridges were more than half completed. As the fog began to thin out, Union work details laboring on the pontoon boats in the frigid water became visible to the Confederate riflemen concealed along the riverbank behind fences and breastworks and in cellars, warehouses, and houses on the south shore. These men were from Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippi Infantry Brigade (13th, 17th, 18th, and 21st Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiments, about 1,500 men in all), as well as the attached 8th Florida Infantry Regiment. They had been placed in the town by Lee to slow down any Union crossing of the Rappahannock in order to gain time for the Southern Army to meet the enemy south of the city.

As the engineers labored to finish their task, Barksdale’s men poured unrelenting small-arms fire into them. At the Upper Bridge, galling fire was directed at the 50th New York, killing a captain and two enlisted men. Support fire from skirmishers of the 7th Michigan and 19th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments did nothing to drive away enemy riflemen, who were protected by the still considerable fog. The bridge parties had to repeatedly abandon their work and seek cover on the Federal side of the river on account of enemy fire.

At the Middle Bridge, Confederate snipers rushed from their hiding places and were joined by two companies of infantry to fire at the hapless engineers, wounding six and piercing the pontoon boats in many places. Here, too, construction was temporarily suspended. By contrast, the Lower Bridge faced an empty plain with only token opposition, and the structure was completed by 9 am. However, owing to the delay at the other crossing points, Burnside pushed back Franklin’s crossing until 4 pm.

When the Federal infantry failed to dislodge the enemy sharpshooters, the mission was given to the artillery. Union batteries roared into action and began putting down heavy suppression fire. Whenever the deadly musketry ceased, Union engineers went back to work on the bridges, only to be driven away again by renewed Confederate fire. This went on for most of the day.

Fredericksburg in Union Hands

With the artillery bombardment a failure, Hunt proposed to Burnside that infantry be sent across the water to root out the murderous Rebel riflemen. Gaining approval of his plan, Hunt collared the first infantry leader he found, Colonel Norman J. Hall, commander of the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, II Corps, and had little trouble convincing him to take the job. Hall ordered the 7th Michigan Infantry to board pontoons and row to the south bank. Some 70 Wolverines composed the first wave.

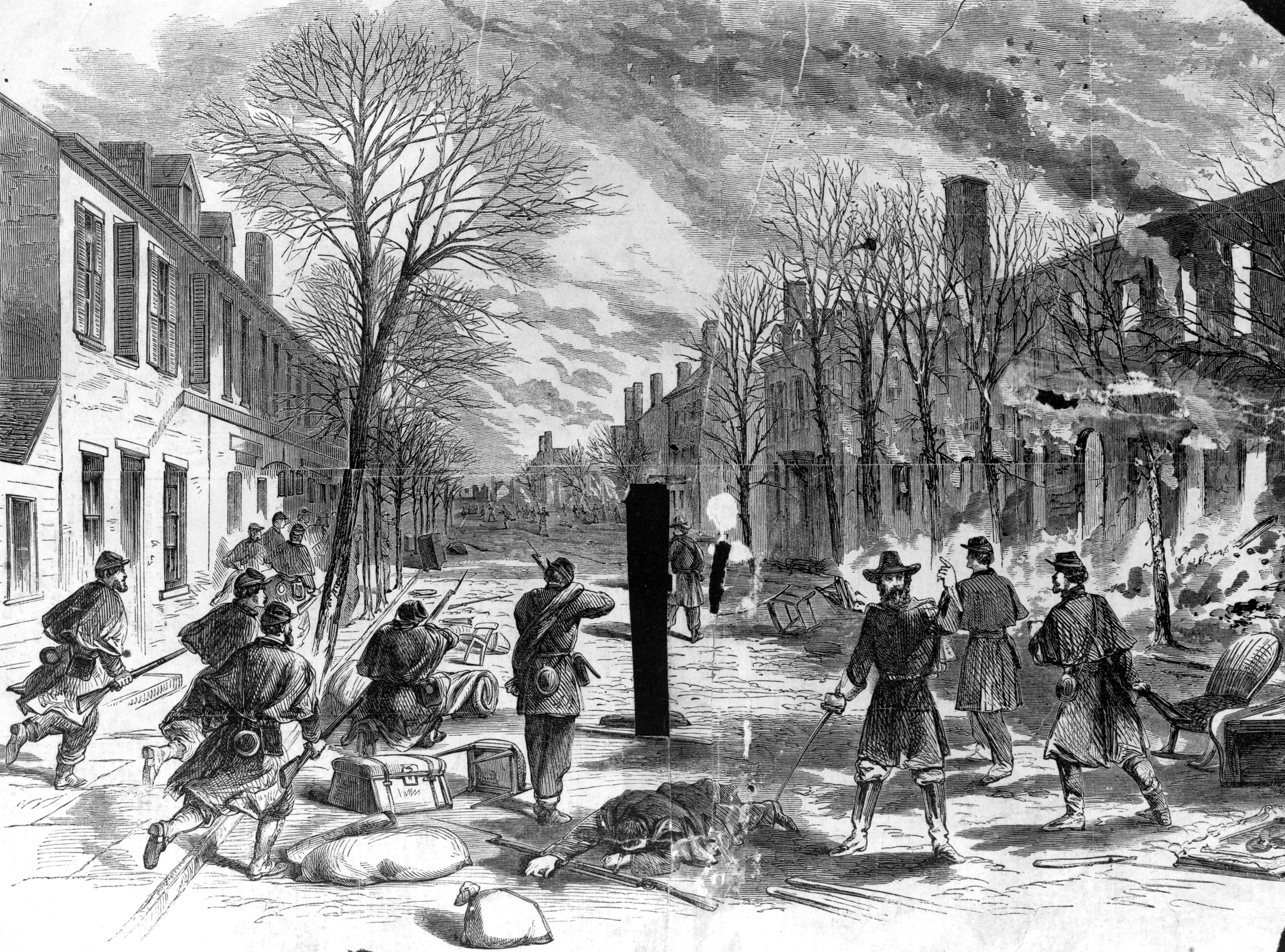

Once on the far shore, they formed under the bank and rushed down Water Street, now Sophia Street, to attack the enemy. In the space of a few minutes, 31 Rebel prisoners were captured and a secure lodgment was effected. The rest of the 7th Michigan and 19th Massachusetts crossed the river as well, fanning out to the left and right of the landing site, with the 20th Massachusetts providing support. While the bluecoats consolidated their position, Union artillery blasted away, allowing the engineers to finish placing the Upper Bridge.

With the Upper Bridge completed, the original Union amphibians were joined by the 42nd and 59th New York Infantry and the 127th Pennsylvania. In columns of four, shoulder-to-shoulder, the Federals advanced into Fredericksburg, all the while being fired upon by Confederates hiding in adjacent buildings and alleyways. At the corner of Caroline and Fauquier Streets, the 20th Massachusetts ran into sweeping fire from the 21st Mississippi, which was acting as a rear guard for the Confederate withdrawal from the city. Slowly the Unionists gained ground, but at a huge loss. The 20th Massachusetts incurred 113 killed and wounded out of 335 engaged. By nightfall, the complete withdrawal of Confederate forces from Fredericksburg ended perhaps the bloodiest street fighting of the entire war.

With the coming of night, the Federals controlled Fredericksburg, but any satisfaction they derived was nothing compared with the satisfaction that Lee felt. The delay caused in taking the town had allowed Jackson’s divisions to join him on December 12. It appeared that Burnside was determined to attack the entire Southern Army in its well-defended positions just below Fredericksburg. Beginning at sunrise on the 12th, the entire Army of the Potomac started to cross the Rappahannock and deploy to the west and south of town. The passage of the Union troops throughout the day brought a wave of looting and destruction to the once-prosperous city.

The Two Opposing Battle Lines

Burnside’s battle plan for the 13th was to seize the military road running along the Confederate front and split Lee’s army in two. Early in the morning, Burnside sent imprecise orders to Franklin that could have been interpreted as an instruction to attack the enemy right or merely to make a diversion toward Prospect Hill, below Hamilton’s Crossing. Two of Hooker’s divisions were to remain near the Lower Bridge to support Franklin. In the meantime, Sumner was told to take Marye’s Heights in the center-left of the opposing line, just to the east of Fredericksburg.

Early on the 13th, Lee’s right was still vulnerable; all of Jackson’s troops had not yet gotten into position. But by the time Franklin initiated his move, 35,000 Confederate soldiers and 54 artillery pieces covered the open plain, which was difficult to negotiate because of the presence of drainage ditches and muddy fields. One glaring weak point was a 600-yard gap between Brig. Gen. James H. Lane’s North Carolina brigade on the left and James Archer’s mixed Alabamians, Georgians, and Tennesseans on the right. Maj. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill, the division commander, assumed the swampy and thickly covered undergrowth would deter any Federal attack on that portion of the field. Just in case, he had placed an infantry brigade under Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg a quarter of a mile to the rear.

Meade’s Assault on Prospect Hill

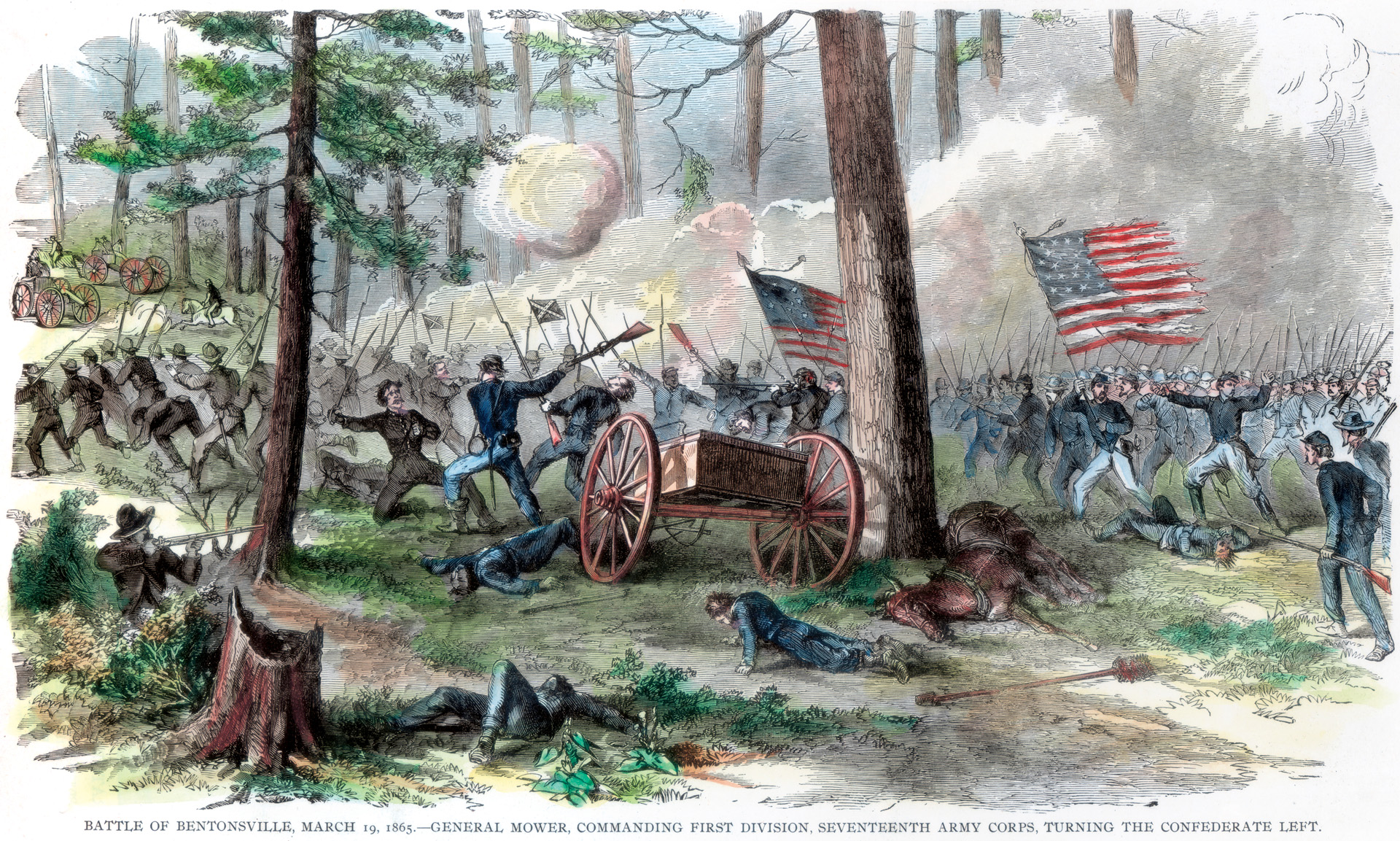

Around 9 am, the fog that had shrouded the southern portion of the Fredericksburg battlefield began to lift. Its dissipation heralded the Federal attack, which was led by the V Corps division of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Meade felt his lone outfit would be able to take but not hold the area around Prospect Hill. Resigned but determined, Meade’s command marched from Smithfield and approached the Richmond Stage Road. As the Federals came closer they were observed by Lee, Longstreet, Jackson, and Stuart. One of the latter’s subordinates, Alabama-born Major John Pelham, Stuart’s horse artillery leader, got permission from his chief to take a single 12-pounder Napoleon and advance beyond friendly lines to engage the oncoming enemy’s left flank.

Moving toward the Union columns, Pelham unleashed shots from his single gun, cutting down dozens of the enemy. Pelham was soon joined by a Blakely rifled piece. In retaliation, five Union batteries zeroed in on the two enemy cannons. Pelham pulled away from the advancing foe but not before his amazing act slowed Meade’s advance and forced the entire division of Abner Doubleday to sit out the rest of the battle to guard against similar threats to the Union left. Lee, who had watched Pelham’s action, remarked emotionally, “It is glorious to see such courage in one so young.”

With the departure of Pelham, Meade’s and Gibbon’s divisions resumed their movement toward Prospect Hill. They were supported by Federal artillery stationed on both sides of the Rappahannock, but the fire caused little damage to the Confederates because the Federal pieces could not see their targets. Confederate artillery, meanwhile, was instructed not to fire until the enemy was within 800 yards. With Gibbon on Meade’s right, their combined 8,000 infantrymen moved forward. As the bluecoats crossed the railroad, 50 enemy cannons opened up, inflicting terrible losses. The Union advance stalled, with many troops either falling or else running back in the direction they came from. The dueling artillery commenced counterbattery fire, with heavy losses on both sides.

When the opposing artillery fire died down, Meade ordered his men to march over the rail line and attack the Rebel infantry line on Prospect Hill. By chance, Colonel William Sinclair’s 1st Brigade of Meade’s division stumbled into the gap between the Confederate brigades of Lane and Archer. The difficult terrain caused the brigade to split apart and prevented any coordination between the different regiments. Nevertheless, the disorganized Federals charged into the unprepared position held by Gregg’s South Carolinians, sparking savage hand-to-hand fighting. Gregg was mortally wounded at this time.

Meade’s men were astride the military road and set to cleave Lee’s army in half, as planned by Burnside. The 13th and 2nd Pennsylvania Reserve Regiments reached the crest of Prospect Hill and were in position to flank Archer’s command. Caught in a crossfire, Archer’s formation was partially destroyed and forced to retreat.

Meade Loses His Hard-Earned Gains

Despite breaching the Confederate line, Meade’s assault was losing momentum, and his fragmented regiments were advancing in the face of withering musket fire from Lane’s Tarheels, who themselves were being flanked on their right. Fortunately for the Federals, Gibbon’s division finally entered the fight. He sent two of his brigades forward, but under effective fire from Lane’s men the advance sputtered to a halt. Gibbon then committed his third brigade. This carried the Federals over the railroad and initiated close-quarters fighting, the bayonet being freely employed by both sides. Lane’s men were forced back.

Although Meade had pierced the enemy line and Gibbon was pressing the Confederates hard, the tide of battle was about to turn. The unflappable Jackson committed Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s hard-fighting division. Archer’s unit was reinforced by Colonel Edward N. Atkinson and Robert F. Hoke’s brigade, while the Virginia brigade under Colonel James A. Walker closed the gap left open between Lane and Archer. Earlier that morning, Longstreet had kidded Jackson about the ocean of blue that was massing before them. “Are you not scared by that file of Yankees you have before you down there?” asked Longstreet. The laconic Virginian had replied without a trace of humor, “Wait till they come a little nearer, and they shall either scare me or I’ll scare them.”

As the Union wave crested and started to recede, Meade begged for reinforcements from Brig. Gen. David Birney’s 1st Division, III Corps. Although this division had been sent across the Rappahannock to help in the attack, it would never enter the battle. By 4 pm, all the gains achieved on the Federal left were given up and the tattered remains of the attacking force withdrew to the shelter of the Richmond Road whence the assault had been launched. On this part of the field, the Confederates had lost 2,338 men to the Federals’ 3,340.

Striking the Confederate Left

With encouraging reports about Franklin’s apparent success on the Union left, Burnside decided to start an attack on the Confederate left directed at the formidable position on Marye’s Heights. The Federal advance would have to travel over mostly open ground along two thoroughfares, the Telegraph and Orange Plank Roads, to reach their objective.

Unknown to the Union commander, Telegraph Road became a sunken road as it wound around the base of Marye’s Heights. The four-foot-high stone fences along each side of the road made excellent fortified positions that could conceal 1,000 men. In the area of the roads, as well as on Telegraph Hill and Marye’s Heights, the Confederates had placed 37 artillery pieces to cover the approaches to the heights. Making it even more difficult for the attackers, an unfinished railroad cut south of the stone wall guarded the flank. Stationed behind the stone wall was Georgia Brig. Gen. Thomas R.R. Cobb’s brigade of McLaws’s division. In support, 200 yards behind Marye’s Heights were Brig. Gen. John R. Cooke’s men of Ransom’s division. Ransom’s own brigade lay within close proximity, while the rest of McLaws’s men held the area south of Hazel Run. Richard Anderson’s division anchored the left flank.

Burnside sent orders to Sumner to “push a column of a division or more along the Plank and Telegraph roads, with a view of seizing the heights in the rear of the town.” The troops that were tasked to carry out the directive were the men of Brig. Gen. William H. French’s 3rd Division and Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s 1st Division of Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch’s II Corps. The third division of Couch’s command, Brig. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s 2nd Division, would stand fast and guard the upper part of Fredericksburg against a possible Confederate incursion.

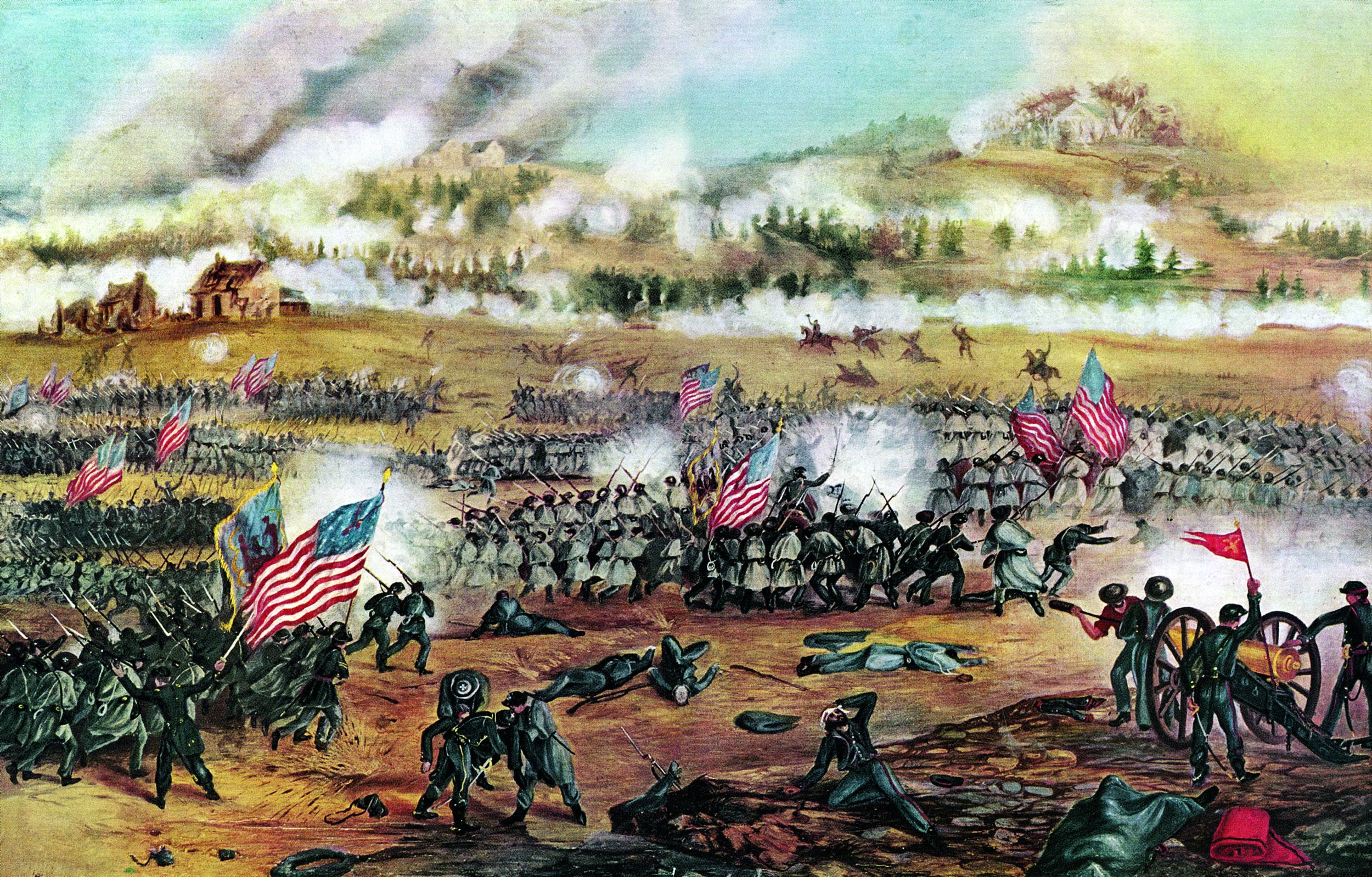

Around noon, French’s men moved out on the designated roads leading to Marye’s Heights just as Confederate artillery started lobbing shells into Fredericksburg. Driving Confederate skirmishers before them, Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s brigade crossed the canal and reformed under the cover of the west bank, taking heavy losses from the enemy artillery. Kimball’s men then charged and reached the swale 100 yards from the stone wall before being ripped apart by rifle fire from Cobb’s infantry and projectiles from the Washington Artillery battery. Kimball was wounded and his men could advance no further. Kimball’s brigade lost at least one-fourth of its original strength in the attack.

As Kimball advanced, Ransom moved Cooke’s men up to Marye’s Heights. Another of French’s brigades, that of Colonel John W. Andrews, 150 yards behind Kimball’s command, was cut to pieces, as was the last of French’s units, Colonel Oliver H. Palmer’s brigade. Entire Union companies fell at once to the devastating hurricane of fire coming from the Confederate line ahead of them.

7,000 Lost on Marye’s Heights

As the advance of French’s troops stalled, Cobb was mortally wounded in the thigh by a Federal artillery shell or sniper shot. Earlier, he had received a note from Longstreet advising him to fall back if pressed. “Well,” said Cobb, “if they wait for me to fall back, they will wait a long time.” The Rebels behind the stone wall had little time to mourn their fallen leader—more Yankees from Hancock’s division were storming out of Fredericksburg and heading in their direction.

Colonel Samuel K. Zook led Hancock’s lead brigade along the railway cut and, despite losing a third of his men, managed to get within 100 yards of the stone wall. Closely following Zook was the Irish Brigade under Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Meagher. The 1,200 Irishmen crossed the millrace at about 12:30 pm while being mauled by the gray artillery. Somehow, a few of the Gaels came within 25 yards of the stone wall and continued trading shots with the Rebels. By that time, three of their five regimental commanders were out of action due to wounds. Lee, watching the determined assault, worried aloud to Longstreet at the strength of the enemy attack. “General,” said Longstreet, “if you put every man on the other side of the Potomac on that field to approach me over the same line, and give me plenty of ammunition, I will kill them all before they reach my line.”

Hancock’s last outfit, Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell’s 2,000-man-strong brigade, followed its brother units into the maelstrom. Soon after it started, Caldwell’s advance broke apart, falling precipitously back to Fredericksburg. By late afternoon, the remnants of French’s and Hancock’s commands found themselves pinned down and unable to go either forward or back due to the intense enemy fire. The only evidence of their gallant assault was three planted stands of colors, drooping unattended in no-man’s-land.

To cover the retreat of the battered divisions of French and Hancock, elements of Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis’s 2nd Division, IX Corps, and parts of Howard’s division attempted to assail the stone wall from the left and right. Their efforts proved fruitless as well, as were those of Charles Griffin’s and Andrew Humphreys’s divisions. By 2 pm, Burnside had tried to drive the Confederates off of Marye’s Heights using 10 brigades; his only reward was the loss of some 7,000 men. The Confederates lost about 1,398 killed and wounded. The Union dead were stacked three-deep in front of the now infamous stone wall. Several Confederates, most prominently 19-year-old Sergeant Richard Rowland Kirkland of South Carolina, the Angel of Marye’s Heights, risked their own lives to take water to the wounded Federals. (Kirkland was fated to die nine months later at Chickamauga.)

“It is Well That War is so Terrible”

Mercifully, the fighting died down as night approached. On the 14th, the troops of both sides remained on the battlefield. The Federals hunkered down in the mud, unable to move because of Confederate rifle fire and occasional artillery rounds. Incredibly, Burnside contemplated renewing the attack on the 15th, but after seeing the condition of his army, he ordered a general withdrawal across the Rappahannock. On the 16th, II Corps led the retreat on the Federal right while V Corps units acted as a rear guard. The operation was completed by 10 pm. The Union fallback was so sudden and stealthy that Lee’s army had no opportunity to interfere with it. The ever-pugnacious Jackson lamented the fact that he had strengthened his position and perhaps encouraged the Federals to retreat. “I did not think that a little red earth would have frightened them,” he scoffed. “I am sorry that they are gone. I am sorry I fortified.”

The Battle of Fredericksburg cost the Union a total of 12,653 casualties; the Confederate lost less than half that amount. As part of its hideous legacy, Fredericksburg sent the morale of the Army of the Potomac to a new low and strained the resolve of the North to carry on the struggle. “It can hardly be in human nature for men to show more valor,” reported one northern newspaper, “or generals to manifest less judgment.” Burnside’s military reputation would never recover, although he retained command of the army for another two months before being replaced by Joseph Hooker.

Surprisingly, the victor of this bloody contest, Robert E. Lee, was criticized by some of his fellow countrymen for not finishing off his opponent before the latter recrossed the Rappahannock. Perhaps Lee had seen enough for one day. “It is well that war is so terrible,” he remarked during the height of the battle, “lest we should grow too fond of it.” There was no chance of that happening—either now or in the foreseeable future.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments