By Nathan N. Prefer

It didn’t look like much—just a speck in the vast ocean. Most travelers spent only a night in the Pan American Hotel and never ventured far from the small adjoining airfield. It was called Wake Island, and until recently, it had been an uninhabited atoll in the mid-Pacific.

Wake Island was V-shaped and consisted of three atolls: Wake, Wilkes, and Peale. Together they contained barely 2,600 yards of sand and coral fringed by a coral reef on which the Pacific pounded loudly. Woods and underbrush covered large tracts of the island. Even the interior lagoon was unsuitable for ships with its coral heads and foul ground. Only seaplanes could land there in 1941.

But Wake’s value lay not in its appearance but in its location. By August 1941, Pan American Airlines had built aircraft landing facilities, a refueling base, a powerful radio station, a pier and a concrete ramp, and then a hotel that made Wake Island a stop for the trans-Pacific traffic between Hawaii and the Orient.

This made Wake Island one of only three American outposts in the far Pacific—and the only way the United States could fly reinforcements to its holdings in Guam and the Philippines. Guam was surrounded by Japanese-held islands and believed indefensible from a major attack, while Midway, another stop on the aerial supply route, would be useless without Wake to support its passage of aircraft.

Wake’s strategic value was recognized in early 1941, and steps were taken to fortify the island against a possible attack. Civilian contractors were shipped to the island to develop a military base. Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Commander-in-Chief, U. S. Pacific Fleet, already feared that this had been delayed too long and stressed again and again the importance of developing the Wake Island base as quickly as possible.

One of the steps he took was to request that a U. S. Marine defense battalion be assigned to defend the base during and after its completion. In 1941 a typical Marine Corps defense battalion consisted of 43 officers and 939 enlisted Marines. They were armed with six naval 5-inch coastal defense guns, twelve 3-inch antiaircraft guns, 48 .50-caliber antiaircraft machine guns, 48 .30-caliber antiaircraft machine guns, six searchlights, six sound locators, and infantry weapons. Due to a shortage of personnel and demands on the services of Marine Corps defense battalions, a full battalion was not available for Wake Island. The 1st Marine Defense Battalion was instead divided up between Pearl Harbor, Johnston Island, Palmyra Island and Wake Island.

The first to arrive, on August 19, 1941, was Major Lewis A. Hohn with five officers and 173 enlisted Marines and Navy Corpsmen. They quickly set up a tent camp (Camp One) separate from the contractors’ more comfortable camp (Camp Two). Because the United States was not at war, the construction efforts of the Marines in building defenses and those of the contractors in building base facilities were distinctly separate.

Although some unofficial cooperation existed between the two groups, each concentrated on its own tasks. In the end, most of the work done by the Marines was done with hand tools—one of the reasons for the soon-to-be-developed Naval Construction (“Seabees”) Battalions.

On October 15 Major Hohn was relieved by Major James P. S. Devereux, the executive officer of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion. Devereux was also designated as the Island Commander until later in the year. Described as a “short man of slight build,” Devereux was 38 years old, a career Marine officer with experience at Pearl Harbor, Nicaragua, the Philippines, and China.

He recalled, “When I arrived on the island, the contractor’s men working on the airfield near the toe of Wake proper had one airstrip in usable condition and were beginning the cross-runway.

“Five large magazines and three smaller detonator magazines, built of concrete and partly underground, were almost completed in the airfield area. A marine barracks, quarters for the Navy fliers who would be stationed on the island, warehouses and shops also were going up on Wake.

“On Peale Island, work was progressing on a naval hospital, the seaplane ramp and parking areas. On Wilkes, there were only fuel storage tanks and the sites of proposed powder magazines, but a new deep-water channel was being cut through the island. In the lagoon, a dredge was removing coral heads from the runways for the seaplanes which were to be based at Wake. Some of these installations were nearly finished; some were partly completed; some were only in the blueprint stage.”

One problem that Major Devereux faced immediately was that his Marines were used to refuel U. S. Army Air Corps B-17 heavy bombers, which were transiting to the Philippines and General Douglas MacArthur’s Philippine-American forces there. With no automated facilities yet installed, his men had to refuel the bombers by hand, a time- and labor-intensive process that reduced the time they had for their own defense work.

Each plane required 3,000 gallons of gas, which had to manhandled and hand-pumped into it by the Marines. This often had to be done at night, further reducing the amount of sleep available to the Marines. Ironically, most of these aircraft were destroyed on the ground on the first day of the new war.

Devereux’s Marines also had to unload the supply ships that kept the garrison and contractors equipped and fed. Again, precious time was taken from building defenses.

Good news arrived on November 2, when another detachment of the battalion arrived, bringing an additional nine officers and 200 enlisted men to augment the Wake Island detachment. The 1st Marine Defense Battalion on Wake Island now numbered 15 officers and 373 enlisted men.

Also encouraging was the arrival of Marine Fighter Squadron 211 (VMF-211) under the command of Major Paul A. Putnam. The ground crews came in by sea and the aircraft by air in mid-November. Also arriving with this shipment was the newly appointed Island Commander, Navy Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, who brought with him the beginnings of a naval air station scheduled to be established on the island. Major Walter L. J. Baylor of Marine Air Group 21 (MAG-21) also arrived to command the service detachment of MAG-21.

By December 6, 1941, Wake Island had the complete armament of a defense battalion, but only about one-third of the Marines to man those guns. This left one complete antiaircraft battery unmanned, and the remaining two were working shorthanded. Only one had its full allowance of fire-control equipment. One had a director but no height-finder.

Also, there was no radar, which would have been particularly useful on a mid-Pacific island where the pounding surf blocked all other sounds coming from the sea. Even the 5-inch coast defense guns, although fully manned, were missing tools, spare parts, and various ordnance items.

Captain Wesley McC. Platt, commanding the forces on Wilkes Island, reported, “At the outbreak of war, weapons had been set up. All were without camouflage or protection except the .50-caliber machine guns, which had been emplaced. All brush east of the new channel had been cleared. The remaining brush west of the new channel was thick and, as a result of this, the .50-caliber machine guns had been placed fairly close to the water line. The beach itself dropped abruptly from two-and-a-half to four feet just above the high-water mark.”

As darkness fell on this day, there were 1,200 civilian contractors and 38 officers and 485 enlisted men on Wake Island. Ironically, it was on December 6 that Major Devereux was able to finally hold the first “General Quarters” drill since the Marines had arrived on the island.

Pan American’s Philippine Clipper had spent the night of December 7-8 (December 6-7 in Hawaii) on Wake Island and prepared to resume its journey early on the morning of the 8th.

As the Clipper took off, Major Devereux was shaving, and most of the Marines were preparing for another day of work. At the U. S. Army communications radio van, recently arrived on the island, an operator was monitoring Hickam Field on Hawaii when a message about an attack on Oahu was received.

Army Captain Henry S. Wilson rushed the message to Major Devereux, who immediately alerted his Marines. And Major Putnam sent up the dawn patrol while on the ground the remaining aircraft were moved to safe positions. The Philippine Clipper was recalled to Wake.

Putnam’s VMF-211 had only been on Wake for four days, and aircraft revetments and access roads were still not finished. As he later recalled, “Work was progressing simultaneously on six of the protective bunkers for the airplanes, and, while none was available for immediate occupancy, all would be ready not later than 1400 hours.”

In a decision he later regretted, Major Putnam decided to leave all his aircraft on or near the field until the bunkers were ready later that day rather than risk damage by moving them over rough terrain to hide them temporarily.

The attack on Pearl Harbor had been the opening strike of the broader Japanese strategy to seize or neutralize the few advanced American bases west of the Hawaiian Islands as quickly as possible. One part of this strategy was for the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Fourth Fleet, under Vice Admiral Nariyoshi Inouye, based in the Marshall and Caroline Islands, to “capture Wake.”

Admiral Inouye’s fleet was small, consisting of a few old cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, and with some Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) troops available to it. Inouye, who had known about his mission since November 1941, was confident that his SNLF force of about 450 Japanese “Marines” could do the job without difficulty.

The Philippine Clipper was loaded with important Pan American personnel and its own passengers and took off for Midway. VMF-211 maintained a combat air patrol around the island, with pilots returning to Wake for fuel and a rotation of pilots. But as they were patrolling north of the island, the IJN 24th Air Flotilla, based on Roi Island in the Marshalls, some 720 miles away, put in their appearance.

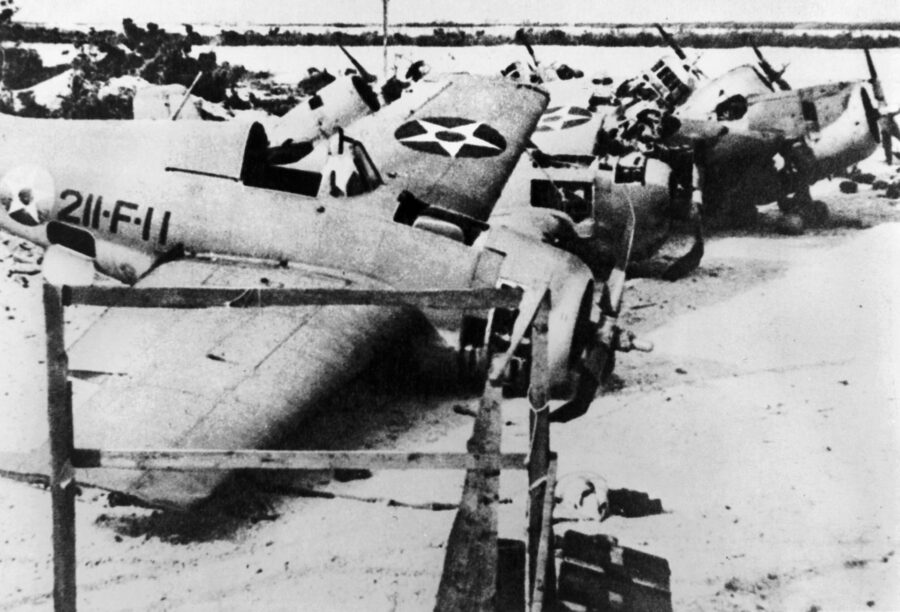

The Japanese airmen headed for the airfield and were only seen once they were already in their bomb runs. They struck the VMF-211 area heavily and, with American planes exploding and burning, flew away, satisfied that they had neutralized Wake’s air defenses.

The Japanese were almost right. They had destroyed or damaged seven of the eight Wildcat fighters on the ground. Even the lone remaining Wildcat was damaged, although not severely.

Additionally, Major Baylor’s air-ground radio installation was destroyed by a direct hit, and aviation gas flamed as the 25,000-gallon storage tanks burned. Many of VMF-211’s tools and replacement parts were also destroyed.

Much worse was the loss of 23 of the 55 Marine aviation personnel who were killed, and 11 others wounded. Three pilots—Lieutenants George A. Graves, Robert J. Conderman, and Frank J. Holden—had also died in the attack; others had been wounded.

In one strike, VMF-211 had suffered 60 percent casualties.

VMF-211’s Combat Air Patrol had missed the Japanese, and, to make matters worse, one of the four remaining Wildcats was damaged when it hit bomb debris on the runway as it landed. Major Devereux was most concerned that the enemy had arrived unheard and unseen until he was already in his bomb run over the island. With no early-warning device and the surf noise constant, early warning of the enemy’s approach remained a major concern.

Damage control parties immediately began dealing with the fires, damaged aircraft, and finding a place for the casualties. The contractor’s supervisor, Mr. Dan Teters, offered the use of his hospital, and his doctor, Dr. Lawton M. Shank, aided Lieutenant (jg) Gustave M. Kahn (MC), the defense battalion’s doctor, in caring for the wounded.

2nd Lt. John F. Kinney and Tech. Sgt. William J. Hamilton of VMF-211 began a series of minor miracles as they set about repairing what aircraft were left to them. An estimated 10 percent of the contractor’s men volunteered to help, and some asked to enlist.

A routine was quickly developed following the hit-and-run attack. General Quarters sounded at 5 am, before dawn. All weapons, phones, and lookout stations were fully manned. The remaining four Wildcats (F4F-3s) warmed up and took off just before dawn. Once they found no enemy in the area, half the Marines on the island began improving the defenses while the other half remained at their guns.

But as the day wore on, the Marines edged closer to their foxholes, since they knew that if an enemy flight took off from the Marshalls at dawn, it would arrive over Wake sometime around noon.

And that is what happened, day after day without respite. But no longer did the Japanese fly unmolested: VMF-211 began to take a toll of the enemy bombers, though they still came.

Fully aware of how vulnerable Wake Island was, planners at Pearl Harbor continued to make plans to send reinforcements to Wake. Admiral Kimmel decided to send a relief force as part of a three-pronged attack to confuse and delay the Japanese.

Vice Admiral Wilson Brown’s Task Force 11, based on the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2), would strike at Japanese bases on Jaluit in the Marshalls while Vice Adm. William F. Halsey’s Task Force 8, based on the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6), was detailed to operate west of Johnston Island, covering Oahu in the event of a returning Japanese strike.

The actual Wake Island relief force was to be Rear Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch’s USS Saratoga (CV-3), which already had VMF-221 on board. But delays, bad weather, and command confusion rendered the attempt a failure.

Meanwhile, the Japanese were acting faster and with more success. Following his orders, Admiral Inouye assigned Rear Adm. Sadamichi Kajioka and his Sixth Destroyer Squadron the task of seizing Wake Island. Flying his flag on the light cruiser Yubari and with six destroyers under his command, Kajioka set sail on December 8 for Wake Island.

Guided to Wake by advance reconnaissance submarines, Kajioka rendezvoused with the 18th Cruiser Division, which was to provide gunfire support for the landing. The cruiser division, under Rear Adm. Marumo Kuninori, consisted of two older ships whose guns would add power to the preliminary bombardment of Wake Island. About 150 sailors of the 2nd Maizuru SLF were carried aboard accompanying transports. If these troops were not enough, then the destroyers would provide landing parties from their crews.

Confident that three days of bombing had reduced the American defenses sufficiently, the task force approached the atoll’s southern shore in the pre-dawn darkness on December 11. Although spotted by the two patrolling American submarines, both failed to properly identify the Japanese and made no reports of their presence. The first sighting of the Japanese invasion force came when 2nd Lt. John A. McAlister and Captain Platt reported lights offshore.

Commander Cunningham ordered an alert. and by 3 am the entire island was on watch. Major Devereux ordered his battery commanders not to open fire until he ordered them to do so. 1st Lt. Woodrow M. Kessler remembered that it was too dark to open fire anyway, as they could not see anything yet.

Major Putnam put his pilots on alert but waited for dawn before launching his remaining aircraft. His and his three senior pilots—Captains Henry T. Elrod, Frank C. Tharin, and Herbert C. Freuler—waited impatiently in their cockpits for the order to take off. On the field, Lieutenant Kinney and his ground crew worked tirelessly to get the troublesome fourth plane ready to fly.

The Japanese opened fire at 5:22 am, moving back and forth, each time getting closer to the island. The barrage set the oil tanks afire while Patrol Boat 32 and 33 approached the shore carrying the SNLF. Still, the Marine guns remained silent. The Yubari continued to fire, with each pass coming closer to the island.

Meanwhile, the VMF-211 planes took off, masked by some high ground between the field and the Japanese. Shortly thereafter, the fourth aircraft was sent aloft, and the four planes rendezvoused at 12,000 feet over the island’s Toki Point. Underwater, the USS Tambor (SS-198) saw the gunfire and moved to a position to take the Japanese under attack.

By this time, the Marines were removing the camouflage from their guns and tracking the enemy ships, and ammunition was placed within easy reach. Finally, Commander Cunningham asked Major Devereux what he was waiting for, and with that Devereux gave the command to open fire.

The first shots rang out at 6:10 with the 5-inch guns blasting at the now-visible targets. Within moments 1st Lt. Clarence A. Barninger’s gunners believed that they had scored hits on the Yubari. Return enemy fire hit near the battery, but aside from a few minor wounds, no casualties resulted.

As Barninger reported, “She [the Yubari] straddled [us] continually, but none of the salvoes came into the position.” Battery A’s gun also hit Patrol Boat Number 33, killing and wounding several men on board.

Meanwhile, Captain Platt on Wilkes Island was having trouble without a rangefinder. Ordered to estimate the range, he did so successfully enough to endanger the transports and forced three destroyers to intercede between his guns and those transports.

Then he observed two transports heading towards Wilkes at high speed. Correctly interpreting these as transports carrying landing troops, he began searching for landing craft in the dark waters. Meanwhile, Platoon Sergeants William D. Beck and Joe M. Stowe opened fire on the transports, the Kinryu Maru and Kongo Maru. They also hit the destroyer Hayate, which was trying to shield the transports, with three quick rounds. With their third hit, the destroyer exploded, taking 167 Japanese sailors with it.

Lieutenant McAlister’s guns then turned on the Oite, another destroyer. After suffering a dozen or more casualties, the Oite turned away. The destroyer Mochizuki was also hit and withdrew out of range.

At the gun positions, Platoon Sergeant Stowe was lightly wounded in the leg and Corporal John R. Dale in the back, but neither wound was serious. Lieutenant Kessler’s guns, commanded by Platoon Sergeants Eugene W. Shugart and Forest Huffman, took on three other destroyers, the Yayoi, Mutsuki, and Kisarage, as well as the cruisers Tenryu and Tatsuta.

Despite enemy shells hitting all around and within the battery position, Battery B continued to fire without casualties. At least one hit on the stern of the Yayoi is credited to the battery.

At this point, VMF-211 joined the battle. The Japanese were now retreating, as explained by Admiral Kajioka’s flagship captain: “Since we had already suffered losses and the defense guns were very accurate, the O.T.C. decided at 0700 to retire to Kwajalein and make another attempt when conditions were more favorable.”

But the American defenders were not yet done. The four Wildcats jumped the Japanese ships, dropping 100-pound bombs from improvised bomb releases, returning to Wake, refueling and re-arming, and then attacking again. The cruisers Tenryu and Tatsuta were hit, and a transport was set afire.

Captain Elrod’s plane was badly shot up, but before he crash-landed on Wake, he placed a bomb on the destroyer Kisaragi, which blew up and sank, leaving no survivors.

The Japanese had been beaten: their first repulse in the Pacific War. They had lost two destroyers sunk and suffered about 500 men killed, against the loss of one American killed. Wake Island was still holding out. It was the only time in the war that coastal defense guns beat off an amphibious assault.

But two of VMF-211’s planes had to be written off due to damage. Undeterred, the remaining two shot down two enemy bombers when the regular noon attack arrived on December 11.

For the Wake Island defenders, the next week was one of repetitious air attacks by Japanese bombers that sometimes hit something important, but mostly missed their targets. Day after day. the Marines and their civilian helpers repaired damage and moved guns to avoid their being hit from the air once they were identified by observer aircraft. At VMF-211 work never stopped on repairing aircraft and trying to build others out of spare parts.

Admiral Kajioka used this time to gather his new strike force. Anxious to “save face” with his superiors, he gathered additional destroyers to replace his losses, repaired his ships—including his flagship Yubari—and received additional support from Admiral Inouye, who sent the modern heavy cruisers Aoba, Kinugasa, Furutaka, and Kako with additional destroyers to join in the renewed attempt to take Wake Island.

Most importantly, Admiral Kajioka received a portion of the Pearl Harbor Attack Force, then on its way home to Japan, in the form of the large carriers Soryu and Hiryu, each with 54 aircraft, as well as the heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma, along with destroyers. This group began flying strikes against Wake on December 21, signaling to the defenders that a Japanese task force was nearby. A landing force of more than 1,200 troops was now included with the assault forces.

Admiral Kajioka left Kwajalein on December 20 and planned to reach Wake early on December 23. Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, now commanding the Wake Island Relief Force, had departed Pearl Harbor four days earlier aboard the USS Saratoga, escorting ships carrying additional Marine Defense Battalion detachments. The force also included four cruisers, an oiler, and a destroyer squadron.

The task force departed Pearl Harbor at mid-day on December 16. The sailors and Marines aboard expected to have to fight their way to Wake, but, despite constant but incorrect reports of enemy sightings, the task force proceeded unchallenged. Yet, because of the oiler accompanying the force, speed was limited to 12 knots, slowing the combat ships considerably.

Warned by Commander Cunningham that the island was now under attack by carrier-borne aircraft, Admiral Fletcher became conflicted. He needed to refuel before entering a possible battle with an enemy task group, but weather prevented refueling operations. He could reach Wake without refueling, but if a battle began, he would be at dangerously low fuel levels.

Finally, on December 21, within 600 miles of Wake Island, he decided to pause to fuel his ships. Admiral Kaijoka’s task force reached Wake the following day.

Wake had been attacked from the air every day but one, and this had whittled down VMF-221 to one or two planes available to oppose the enemy. News that a relief expedition was on the way bolstered morale.

On December 22, the last two of Wake’s Wildcats were shot down while fighting off the daily attack. Major Putnam’s men turned themselves over to Major Devereux as infantrymen and took up defensive positions around the airfield.

This time the Japanese came in silently. Knowing of the accuracy of the coastal defense guns, they fired no barrage before sending in six landing barges to Wake’s south coast. Each barge carried about 50 men, and the two patrol boats that headed for Wilkes Island carried 1,000 men each from the Maizuru 2nd SNLF.

With orders to “seize Wake Island at all costs,” including “beaching the destroyers if necessary,” the Japanese landed a picked force—the “Takano Unit”—on Wilkes Island in pitch darkness. As the enemy approached in the barge, Captain Platt turned on his searchlight and illuminated the landing force. Marine Gunner Clarence B. Mckinstry opened the final battle for Wake Island with a .50-caliber machine gun.

At Devereux’s command post, 2nd Lt. Arthur A. Poindexter commanded a reserve force of Marines and 15 sailors led by Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class James E. Barnes. Knowing that some machine guns at Toki Point were not manned, he requested and received permission to take his men there and man those guns.

Likewise, 2nd Lt. Robert M. Hanna gathered a scratch crew to man a 3-inch gun set to defend the airfield. Devereux also ordered Major Putnam to send 20 of his men in support of Lieutenant Hanna. The lieutenant and his crew were soon firing point-blank into Patrol Craft Number 33, wounding the captain, navigator, and five others. Japanese scrambled off the ship while behind them it burst into flame.

Flames from Patrol Craft 33 illuminated Patrol Craft Number 32 further down the beach. Lieutenant Hanna shifted his fire to the new target and blew holes in its sides. The crews of both vessels abandoned ship and swam ashore to join the ground troops.

Protected by Major Putnam’s grounded aviators, the battle raged until the Japanese forced the Marines to withdraw, leaving only the gunners surrounded on three sides. Everywhere Marines and their Navy and civilian volunteers fought the Japanese landings. Lieutenant Poindexter and some men saw some barges in the surf, seeking a landing place. He gathered a small force and waded into the surf to toss grenades into these barges.

As the battle went on, communications began to fail. Major Devereux lost contact with Lieutenant Hanna, with VMF-211 at the airfield, and with Battery A at Peacock Point. Soon, all he could contact was Captain Platt on Wilkes Island.

Devereux knew that the island was under attack everywhere but had no idea how it was progressing. He organized a new reserve force from Captain Bryghte D. Godbold’s men on Peale Island, which did not seem to be threatened; these men he sent to support Lieutenant Hanna.

The Japanese were now also landing from within the lagoon in rubber boats, further enveloping the Marine defenses, and Japanese cruisers began bombarding the island in support of the ground assault.

Groups of Marines soon found themselves surrounded or isolated while the Japanese passed them by, moving across the island. Major Putnam’s Marines were isolated around the airfield. He told his men, “This is as far as we go.” Six hours later they were still holding that position.

By 5 am on December 23 it was clear that the Japanese had established themselves on the atoll. It was at this time that Commander Cunningham sent his soon-to-be famous message to Pearl Harbor that read, “Enemy on island, issue in doubt.”

Outnumbered by more than two-to-one, the Marines, sailors, and civilian volunteers continued to fight for their island. Major Putnam’s survivors still held the airfield, despite being surrounded. Batteries A and E were manned and ready to fire on any Japanese ships foolish enough to approach within range. Individual Marine machine-gun posts were mostly surrounded and under attack by increasing numbers of Japanese.

Major Potter, the executive officer, now assembled the last reserve force available— administrative, service, and supply personnel—and formed a final defensive line 100 yards south of the command post. These 40 men were to block the north-south road. Major Devereux ordered Captain Godbold to bring his entire Battery D to the command post for assignment as infantry.

Soon Lieutenant Kessler, still on Peale Island with his Battery B, reported Japanese flags flying all over Wilkes Island; a large Japanese flag flew over where Battery F was posted. Major Devereux could only conclude that Wilkes Island had fallen.

As daylight broke over Wake, a clear picture of the vast Japanese armada that surrounded the island was apparent to the defenders. Three destroyers, led by the Mutsuke, approached to fire on Marine positions on the island, but Battery B on Peale Island was ready for them, and, after being hit, the Mutsuke and its companions turned away. At Peacock Point, Battery E was also soon engaged with naval aircraft flown off the carriers Soryu and Hiryu. Although outnumbered, outgunned by naval ships, and under air attack, the Marines fought on.

By early morning, Major Devereux believed that the Japanese had possession of Wilkes Island and a good part of Wake Island. He had no reserves left and no reinforcements available. Shortly after 7 am, he called Commander Cunningham and told him that organized resistance would not last much longer. He asked about the relief force, only to be told that it would not arrive in time.

Deciding that additional resistance would be useless and would only waste valuable lives, Cunningham and Devereux decided upon surrender. At 7:30, Major Devereux carried a white flag out of his command post and walked towards the approaching Japanese.

It was only later that Devereux learned that Wilkes Island had not fallen to the Japanese. Under the direction of Captain Platt, Gunner McKinstry and Lieutenant McAlister, the Marines there had been hard-pressed for some time, but had then launched a counterattack that all but eliminated the Japanese forces on Wilkes.

The “Takano Unit” of the 2nd Maizuru SNLF had landed and been put under fire immediately. In a series of brutal back-and-forth actions, the Marines had eventually prevailed and pinned the survivors of the SNLF on the beach, where they were wiped out. Four Japanese officers and 90 men were counted killed in this battle, and two wounded were captured. Four others played “dead” among the casualties until the surrender. Captain Platt had the Japanese flags removed, but not until after the reports of them flying “all over” Wilkes had reached Major Devereux.

The Marines had lost all the equipment of VMF-211 and the 1st Marine Defense Battalion. The Marines had suffered 20 percent casualties but killed an estimated 500 Japanese on December 11, and on the 23rd another 100 on Wilkes Island and at least another 80 on Wake Island. Final totals for Japanese casualties in the battle come to at least 700 killed and an unknown number of wounded.

Twenty-one enemy aircraft are credited to VMF-211 and the antiaircraft gun crews. Another 51 were reported by Japanese sources to have been damaged. The Americans lost 49 Marines killed and 32 wounded. Additionally, three sailors had been killed and five wounded, and about 70 civilians had died and 12 were wounded. The five soldiers of the radio relay station all survived unhurt.

After Wake Island surrendered, several atrocities were perpetrated by the Japanese. Chief among these was the murder of about 100 of the civilians left behind on Wake Island after the bulk of the military and civilian personnel were sent to Japan. These men were forced to continue to work on defenses, but the American blockade of the island from 1942 through 1943 brought the Japanese garrison to the early stages of starvation.

Unable to feed them, unable to evacuate them, and fearing an imminent U.S. invasion, the Japanese commander, Captain Sakaibara Shigemitsu, decided to execute the remaining civilians, which occurred on March 6, 1943.

After the Wake Island operation, many of the Japanese went on to other combat actions. Rear Adm. Kajioka took part in the campaign in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands before being posted to command an escort fleet, where he was killed in September 1944.

His superior, Admiral Inouye, was relieved of his command in October 1942 and made the head of the Naval Academy before becoming Vice Minister of the Navy. He survived the war.

Rear Adm. Sakaibara, formerly Captain, was tried by a war-crimes commission and executed for the killing of civilians on Wake Island. When the Americans returned to Wake in September 1945, 609 Japanese soldiers and 653 sailors made up the garrison. Bombing, malnutrition, and disease had killed an estimated 1,288 others. Another 974 men had been evacuated from the island. The hospital held 405 bedridden patients.

Commander Cunningham, Major Devereux, Major Potter, Major Putnam, and the other American survivors spent the rest of the war as prisoners of war in various camps in China and Japan. Several, including Cunningham, attempted escapes; Lieutenants Kinney and McAlister succeeded. Many others perished in the brutal conditions of the POW camps.

Although defeated, they had not lost their pride. A large group of Marines under Sergeant Edwin F. Hassig was marching to a POW collection point after the surrender and passing a very depressed Major Devereux. They were partially stripped, unshaven, many without shoes, limping with heads down and shoulders bent. Seeing his commanding officer, Sergeant Hassig bellowed, “Snap outta this stuff! Goddammit, you’re Marines!”

Instantly, they raised their heads, squared their shoulders, and marched past Major Devereux in perfect cadence. What they had accomplished on Wake Island would inspire Americans throughout the remaining years of the war. The words “Remember Wake Island” were soon appearing on recruiting posters all over America.

Dr. Nathan Prefer, a former Marine reservist, is a college history professor and the author of several books on military history. He lives in Fort Myers, FL.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments