By Colonel (USAF, RET.) Jeff Patton

Pantelleria is a small volcanic island rising out of the Mediterranean Sea 37 miles east of the Tunisian coast and some 63 miles southwest of Sicily. Since its occupation by the Carthaginians in the 7th century bc, the island has been used as a military outpost by a succession of conquerors: Carthaginians, Romans, Arabs, Aragonese, Turks, the Kingdom of Sicily, and finally the Kingdom of Italy.

The island’s strategic location midway in the Sicily Channel made it the ideal location for controlling access of shipping sailing from the eastern to western basins of the Mediterranean. It was Pantelleria’s misfortune to be located in such a critical area and along the corridor that the Allied forces invading Sicily would travel that caused it to become the target of an unprecedented bombing campaign in the summer of 1943.

President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met at Casablanca, Morocco, in January 1943 to decide the future joint strategy of the Allied powers.The conference started with the British and American general staffs at odds on the way ahead.

General George Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, advocated a cross-Channel invasion of France from Britain as soon as possible. The British did not feel there would be sufficient resources, especially landing craft, to support an invasion until 1944 and so, instead, pushed for action against what Winston Churchill famously called “the soft underbelly of Europe.”

Both Churchill and Roosevelt were well aware of the incessant complaints of Soviet Premier Josef Stalin that the Red Army was the only one fighting the Nazis and demanding that Churchill and Roosevelt open another front in Europe to relieve the pressure on the Soviet Union. Underscoring his point was his absence at the conference due to his preoccupation with the desperate fighting around Stalingrad at that moment.

A Mediterranean strategy was agreed upon by the Anglo-Americans, but exactly where to launch an attack was also debated. For Churchill, with an eye on protecting the British Empire in the postwar world, the obvious choice was German-occupied Greece. Here Allied troops would be able to tie down German divisions that might otherwise be used elsewhere and, perhaps more importantly, halt the advance of any post-war Soviet march toward Egypt and the Suez Canal.

The Americans wanted to invade Corsica to threaten an invasion of the peninsula of Italy or the south of France, thus keeping the Germans wondering. In the end, the two Allies agreed that Sicily offered the best invasion option due to its short distance from their forces in North Africa, the element of surprise, and the ability to provide air cover from existing bases in North Africa.

Invading Sicily had the added advantage of taking the fight to an Axis homeland and requiring the Germans to divert divisions from the Eastern Front to shore up their Italian allies. Allied intelligence estimated that the poor state of Italian transportation infrastructure would limit the Germans’ ability to extricate their divisions and turn Italy into a giant sponge for Wehrmacht resources.

But before the Allies could invade Axis-occupied Europe, Pantelleria, the five-by-eight-mile bone in the throat of the Sicily Channel, would have to be dealt with.

Pantelleria had some obvious physical advantages that favored its fortification. It had little in the way of beaches. The island has steep cliffs that plunge almost vertically into the sea around most of its circumference. Its only natural landing area for amphibious assault craft is the port area on the island’s north coast.

It has little vegetation; its few crops are largely caper bushes and grape vines. It has few livestock and a relatively small civilian population. The island rises to more than 2,700 feet above sea level on the summit of aptly named Montagna Grande (Big Mountain), from which a commanding view of most of the Sicily Channel is available.

In the 1920s, Italian leader Benito Mussolini established a penal colony on the island and in 1936 began fortifying it during his war in Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Fascist propaganda called Pantelleria the “Italian Gibraltar,” with the aim for it to act as a counterweight to the British base at Malta and the French at Bizerte.

The island was defended by coastal artillery placed in open revetments protected by rocks and concrete. Twelve Schneider-Ansaldo 152mm guns with a 10-mile range were complemented by 13 120mm guns with an effective range of eight miles. Antiaircraft protection was provided by 75 76mm dual-purpose guns, as well as 18 20mm rapid-fire guns and more than 500 8mm machine guns.

The coastline was dotted by grottos, some of which had been enlarged by engineers to hold refueling and replenishing anchorages for submarines and motor torpedo boats. By 1940, the island garrison had grown to 11,420 Italian defenders and some 600 German troops that manned the Freya radio direction-finding stations on the summit of Montagna Grande.

In addition to fixed gun emplacements and protected anchorages, Pantelleria hosted an enormous underground hanger at its airfield that had been blasted out of a rocky cliff. The structure was the largest underground hangar built by any nation in World War II.

Measuring more than 1,000 feet in length, 85 feet wide, and 60 feet high, the cavernous space was built to accommodate 60 Macchi C.202 fighters and six Savoia-Marchetti 79 three-engine torpedo bombers, plus workshops, storage areas, and 400 cubic meter storage tanks for gasoline. All this was protected by blast-proof steel doors covering the entrance.

Even before the final surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia on May 13, 1943, planning for Operation Husky, the Allies’ invasion of Sicily, had begun. General Dwight D. Eisenhower had been given the overall command of Allied forces for the invasion, and his staff was given the lead for invasion planning.

Their initial thoughts were that Pantelleria would be too tough a nut to crack and the Allies would risk losing valuable resources taking the island that would be better used in the main invasion of Sicily. Eisenhower, in his memoir Crusade in Europe, agreed.

He observed, “Topographically, Pantelleria presented obstacles almost scary for an assault. Many of our commanders, officers of staff, and experts were strongly opposed to the operation because a failure would have had a discouraging effect on the morale of troops to be used against the coast of Sicily.”

Yet Eisenhower saw great advantages to having Pantelleria in his hands: enhanced air cover for the Allied landings and naval operations in Sicily, use of the Pantelleria airfield for search and rescue forces, removal of the German early warning radio direction-finding equipment, installation of a navigational aid on Montagna Grande, and eliminating the island as a refueling base for enemy torpedo boats and submarines.

Intelligence reported that the island was garrisoned by only five Italian infantry battalions that had not seen combat, eight machine-gun companies recruited from the Frontier Guard that kept watch on alpine borders, and artillery units and antiaircraft gunners drawn from militia units. In the opinion of the intelligence analysts, the morale of these troops was probably not high, and they could be expected to perform poorly under the terror of intense bombardment.

However, the state of the defenders’ morale was just a guess. To provide a realistic estimate of the fighting ability of the enemy troops, the British launched three small-scale commando raids to capture prisoners for interrogation.

The first two raids were unable to put a raiding party ashore due to rough sea conditions, but the third landed nine commandos at night along the north coast. The commandos discovered the Italians had posted sentries approximately every 100 yards along the coast; they captured one, but not before he sounded an alarm. In their ensuing rush back to the rubber boats they had left at the foot of a cliff, the commandos got into a firefight, killing three defenders and having one of their own badly wounded.

It quickly became apparent that the raiding party would be unable to descend the cliff with an uncooperative prisoner, so they let him go and left their badly wounded comrade behind.

By early May, Eisenhower had changed his mind about not assaulting Pantelleria. On May 10, he directed his staff to begin planning Operation Corkscrew, the seizure of Pantelleria.

This was not the first time the Allies had drawn up plans to invade Pantelleria. In 1940, the British had planned an assault on the island to eliminate the threat to British shipping in the Mediterranean, but the threat of enemy air attacks by the movement of German fighter and dive bomber squadrons to Sicily caused the plan to be abandoned. This time, however, the Allies anticipated having total air superiority, and the planning went ahead.

The date picked for the invasion of Pantelleria was June 12, 1943. The date was chosen as the latest that the island could be seized and the airfield and supporting infrastructure repaired for Allied air forces to use to support the July invasion of Sicily.

The British 1st Infantry Division was chosen as the assault force. The significance of using the 1st Infantry Division was not only practical, as it had received some amphibious training in England, but also symbolic. The 1st Infantry Division was one of the last units to be evacuated from the European mainland at Dunkirk and now was destined to be the first Allied unit to step onto European soil again.

Eisenhower, however, thought an invasion might not be necessary. In a letter to Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz, the commander of Northwest African Air Forces, Ike explained that he wished to make the upcoming Operation Corkscrew “a sort of laboratory to determine the effect of concentrated heavy bombardment on a defended coastline.”

He wanted the Allied air forces to “concentrate on everything” so that the damage to the island, its military garrison, its equipment and morale would be “so serious as to make that landing a rather simple affair.” He remembered the effect on morale of the heavy shelling of the defenders of Corregidor the previous year and wanted “to see whether the air can do the same thing.”

Lieutenant General Spaatz’s Northwest African Air Forces had several subordinate units, two of which—the Northwest African Strategic Air Forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle and the Northwest African Tactical Air Forces under Air Vice Marshall Arthur Coningham—would provide the aircraft for the bombing “laboratory” on Pantelleria.

These two commanders had at their disposal 1,017 aircraft of all types, the majority of which were fighters and bombers. The Corkscrew planners relied heavily on Doolittle’s strategic air forces for most of the hitting power. This force consisted of four groups of Boeing B-17s, two of North American B-25s, three of Martin B-26s, three of Lockheed P-38s, and one of Curtiss P-40s.

The British contribution to Doolittle’s command included several wings of Wellington medium bombers. While the pursuit group’s main task was providing escort to the bombers, they also participated in strafing and dive bomb attacks on the island.

The Corkscrew planners divided the air attacks on Pantelleria into two phases. From the end of May through June 6, 1943 (D-5), the island would be subjected to increasingly heavy bombardment. From June 7 (D-4) until dawn on June 11 (D-day), the island would be attacked around the clock with an intensity growing from 200 sorties on the first day to 2,000 sorties on the last day.

For the second phase, Doolittle’s forces would be joined by Air Vice Marshal Coningham’s tactical air force. This force was comprised mostly of North American A-36 dive bombers and P-40s. One of the tactical air force’s P-40 squadrons was the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the famed “Tuskegee Airmen,” which had just arrived in Tunisia the month before. The escort and attack missions against Pantelleria would be the first combat for the black airmen.

The deployment strategy chosen by Corkscrew planners would task the American aircraft to fly the day missions and leave the night bombing largely to the RAF with their Vickers Wellingtons. The Casablanca Conference had just recently concluded that the Allies would employ this tactic of round-the-clock bombing in their air campaign against Germany. Pantelleria would be their first attempt to bring day and night bombing to the enemy.

To augment the air bombardment, a Royal Navy strike force of four cruisers, eight destroyers, one gunboat, and 10 motor torpedo boats was organized to shell the island from time to time. These attacks would be aimed not so much as to inflict great damage but to test the island’s defenses and make the coastal artillery unmask its positions for targeting by the air forces.

These periodic shore bombardments were also directed against various targets on the island to keep the defenders guessing as to the direction of the impending assault. This strike force was augmented by other patrol boats to form a blockade of Pantelleria, preventing resupply by sea from Sicily. The blockade was integral to the plan of forcing the island to surrender prior to an invasion.

A U.S. Geological Survey report on the island stated it lacked any surface water. Its sources of fresh water were limited to a few springs in the volcanic rock, a small water desalination plant, and perhaps some underground cisterns for water storage. These sources were deemed adequate for the prewar civilian population of about 10,000, but with the augmentation of almost 12,000 military on the island the garrison and the civilian population faced water shortages.

Despite the presence of a blockading force around Pantelleria, the island was never totally isolated. Supplies continued to be brought to the island largely at night by small fishing boats and ferries throughout the air campaign. In addition, the occasional Junkers Ju-52 transport planes were able to bring supplies to the island and to evacuate almost all of the German troops.

Photoreconnaissance flights over the harbor of Pantelleria during the last week in May showed small craft had offloaded an estimated 530 tons of supplies overnight.

Air power had never before been applied to the problem of neutralizing strongly defended, well-manned fortifications from the air. Even under ideal conditions, the task was daunting. The planners of the upcoming “laboratory” on aerial bombardment were faced with a dilemma. With all the air power at their disposal, how could they best apply it to the garrison on Pantelleria to force surrender without the need of a seaborne invasion?

The answer came from an unlikely source: a South African-born primate research anatomist at the University of Oxford named Solly Zuckerman. He had volunteered his services to the British government at the outbreak of the war and had been involved in several research projects, one of which was the study of the effects of bombing on people and buildings.

The British Combined Operations Staff had offered to loan Zuckerman to the North African Air Force campaign planners to analyze the relation between effort and effect of the bombing of Pantelleria. This relation of effort and effect became the basis of the science of Operations Research—the application of analytical methods to predict results and make better decisions.

Zuckerman’s analysis of heavy bomber accuracy indicated that to destroy a gun position a 1,000-pound bomb would have to land within eight yards of the target. This would yield a circular area of destruction of 200 square yards. Secondary effects of the explosion, such as shock wave, shrapnel, and earth upheaval, would extend the vulnerable area to 600 square yards. To achieve this accuracy, as many as 400 1,000 pound bombs would have to be dropped.

With more than 100 identified gun positions on the island, it was clear that despite the armada of bombers at their disposal the Allied air forces could not knock out the defenses of Pantelleria in the time allowed.

Zuckerman reasoned that if as little as 30 percent of the guns could be rendered non-effective (i.e., two out of a six-gun battery) the remainder of the guns would be silenced for secondary reasons. These reasons included damage to fire control optics, casualties among the gun crews, disruption in communications, interdiction of ammunition resupply to the guns, and demoralization of the surviving crewmembers due to repeated exposure to the concussive effects of bombing.

A 30 percent reduction in the enemy’s defenses was deemed achievable by the resources at the planners’ disposal, and thus Zuckerman’s analytical methods became the cornerstone of the Corkscrew air campaign.

Immediately after the surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia on May 13, 1943, the focus of the Northwest African Strategic Air Forces was turned on Pantelleria. Bombing began in earnest on May 18 with U.S. fighter bombers and medium bombers by day and RAF Wellingtons by night. Early targets were the town and port facilities and the airfield.

In accordance with the targeting plan, the tonnage of bombs dropped increased almost daily, and new targets were chosen or old targets revisited based on daily reconnaissance flights over the island. By the end of May, 90 tons of bombs were being dropped daily.

On June 1, the Northwest African Strategic Air Forces heavy bombers, the B-17s, joined the attack. Early raids on the airfield by fighter-bombers strafing and medium bombers dropping 20-pound fragmentation bombs had destroyed most of the aircraft dispersed in the open surrounding the runway; however, no significant damage had been observed to the underground hangar complex.

On that day, a P-38 pilot skipped a 1,000-pound bomb into the blast door of the hangar but caused little damage. Several more attempts at skip-bombing the hangar’s entrance would be attempted in the coming weeks, but the structure and its contents remained undamaged throughout the campaign.

Early on, it became obvious to targeting planners that Professor Zuckerman’s seemingly pessimistic estimates of the number of bombs needed to destroy a target were being borne out by the facts. The bombs available to the Allied air forces were 1,000-pound, 500-pound, and 250-pound general-purpose bombs with either a 0.25-second delay fuse or instantaneous fusing options. These thin-walled bombs were designed to maximize their blast effects and had minimal penetrative capability against hardened targets.

Photo interpreters observed that instantaneous-fused bombs were having no effect on guns in revetments unless they scored direct hits, and the delayed-fused weapons would sometimes break apart on the volcanic rock prior to detonation.

The U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) would introduce new types of general-purpose bombs—the M64 500-pound and the M65 1,000-pound bombs—with thicker cases and better fusing options in 1943, but they would not arrive in theater until after the invasion of Sicily.

Of course, any bomb has to be accurately delivered to be effective, and the USAAF had the most accurate bombsight in the world on its heavy and medium bombers. The Norden bombsight was an analog computer that calculated the bomb’s trajectory based on current flight conditions such as altitude, temperature, wind, and ground speed.

During testing in the 1930s, it showed remarkable accuracy when finely tuned and under perfect conditions. The Carl L. Norden Company demonstrated a circular error probable (CEP) of 75 feet from a bombing altitude of 20,000 feet during prewar testing, but in operational service the accuracy was much less. In 1940 the average score of an Air Corps bombardier using the Norden sight was 400 feet. Under combat conditions, it was worse.

USAAF planners calculated that a B-17 had a 1.2 percent probability of dropping a bomb within 100 feet of a target from an altitude of 20,000 feet. The idea of pinpoint daylight precision bombing was good in theory but was outside the practical capabilities of the Allies in World War II. To obtain the desired effects, massive tonnages of bombs would have to be dropped. This lack of level bombing accuracy caused the U.S. Navy in the Pacific to abandon level bombing and rely almost exclusively on dive bombing.

The various fighters assigned to Corkscrew exclusively used dive bombing and strafing for their weapons delivery and obtained much better accuracy than the level delivery medium and heavy bombers but could not match their weight of bombs carried. The P-40s could only carry one 500-pound bomb, the A-36s could carry two, and the twin engine P-38 could carry two 1,000-pound bombs maximum. The B-17’s normal bombload, by contrast, was 10 500-pound bombs or five 1,000-pounders.

As a result, the heavy bombers were given large area targets such as the airfield, port, and dock facilities, and the town of Pantelleria itself while the fighters were assigned to pinpoint targets such as gun positions.

Augmenting the aerial bombardment was naval bombardment. On May 31, the Royal Navy light cruiser HMS Orion, escorted by two destroyers, shelled the harbor area of Pantelleria from a range of 13,000 yards. After expending 150 rounds of six-inch and smaller caliber rounds on the docks, the ships withdrew, noting that there was little return fire.

The next day the cruiser HMS Penelope, along with two destroyers, engaged in a similar bombardment. This time, five Italian coastal artillery batteries responded and scored a direct hit on Penelope with a 152mm round; however, the shell was a dud and caused little damage and no casualties.

On the following two days, HMS Orion resumed the attack. Return fire from the shore batteries was sporadic and inaccurate. The rather feeble response to the naval shelling was interpreted as either the result of the daily bombing raids by the North African Air Forces having degraded the shore batteries’ capabilities or the gunners being reluctant to highlight their positions for counterbattery fire from ships or bombing from aircraft.

To test the amount of damage inflicted on the shore batteries, the Royal Navy staged a full-scale naval bombardment on June 8. The task force consisted of light cruisers HMS Newfoundland, Aurora, Penelope, Euryalus, and Orion accompanied by eight destroyers and three motor torpedo boats to serve as a screen against possible U-boat attack.

Aboard his flagship HMS Aurora were the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet, Vice Admiral Andrew Cunningham and the Supreme Commander General Eisenhower to observe the bombardment and the Italian response.

The naval attack was broken down into two parts. In the first part, the five cruisers shelled the mole and dock area of the port immediately following a strike by B-25s and P-38s on the same area. The second part consisted of the destroyers closing to within 2,000 yards of shore to entice shore batteries to reveal themselves by firing at these tempting targets. Only an estimated 30 rounds were fired by the defenders, all of which missed their targets.

The final portion of the attack saw the three motor torpedo boats close to within 300 yards of the port, which succeeded in provoking several 8mm machine-gun nests to open fire on them.

The attack lasted about 90 minutes before the British withdrew and the results of the shelling were appraised. The conclusion was that of the 16 known coastal artillery batteries in range of the British warships only four returned fire; one fired until it was silenced by a cruiser, and the other three responded only intermittently.

The result of this action convinced Eisenhower that critical shore defense batteries had been rendered ineffective and the daily analysis of bombing effectiveness that crossed his desk was too conservative. He told his staff that he had every confidence that plans for the upcoming assault on the island could be adhered to.

He also opined that since the bombardment would be intensified and continued for the next three days until June 11, the morale of the defenders would be sufficiently shattered for the landing troops to capture Pantelleria with relatively few casualties.

Giuseppe Ferrara was a 24-year-old NCO in the Regia Marina (Italian Royal Navy) when he first set foot on dusty, sun-baked Pantelleria in 1939. He had previously been assigned to the heavy cruiser Duca d’Aosta during the Spanish Civil War and was trained as a machinist.

When he was assigned to Pantelleria to run the fuel depot there, “My heart sank,” he recalled in his memoirs. “I came from a fertile land of Sarno [30 miles east of Naples], fertile and rich in water and was now in a dry land without even a source of water.”

He describes drinking from the stagnant water cisterns of the civil population’s houses or rusty storage tanks owned by the military. The truly adventuresome drank from the couple of springs that came out of the volcanic rock, but the water stank of sulfur. He didn’t have much time for sightseeing or feeling sorry for himself. The entire island was a construction site with work in progress expanding the port facilities, leveling two volcanic cinder cones to create a flat landing field for the airport, and tunneling into the adjacent hill to build the enormous underground hangar.

As time went by, Ferrara began to enjoy the assignment. “The people were hospitable and had great local food and wine and, something very important to me, the girls on the island were very beautiful.” The next year, 1940, he met a 16-year-old girl and “it was love at first sight.” He received permission to marry, and a few months later his daughter was born.

The quiet life of peacetime garrison duty was interrupted in June 1940, when Italy declared war on France. Shortly thereafter, the island began receiving reinforcements and additional aircraft, supplies, guns, and German technical experts to install and operate three Freya radio direction-finding posts.

Ferrara was in charge of the main fuel supply depot on the island at Villa Silvia outside of town. This depot consisted of two large fuel storage deposits that were buried deep underground. He did a brisk business refueling MAS motor torpedo boats and submarines that attacked British naval convoys that passed by Pantelleria as well as providing fuel to the airport.

In June 1942, the island figured prominently in the Naval Battle of Pantelleria. The British sent a heavily escorted resupply convoy from Gibraltar to their besieged base on Malta. The Regia Marina dispatched two cruisers and four destroyers and intercepted the convoy near Pantelleria, sinking two destroyers and four merchant ships, including an American tanker, the SS Kentucky.

Savoia-Marchetti SM-79 torpedo bombers from Pantelleria and Sicily finished off several damaged vessels. Only two of the original six merchant vessels made it to Malta and the loss of aviation gasoline aboard the Kentucky severely hampered air operations out of Malta for weeks.

The day after this action in the Sicily straits, Ferrara was ordered to take a sailing vessel from the harbor of Pantelleria to search for survivors of the British merchantmen sunk the previous day. He found several survivors from the merchantman Burdwan, whom he took aboard and returned to Pantelleria. One of the survivors was the ship’s doctor. “I offered him a cigarette. He had a badly burned face and was suffering much pain, but he disdainfully refused. Evidently, he had not yet digested the defeat.”

Other boats from Pantelleria rescued other British sailors. When he arrived in port, Ferrara saw these prisoners being offered hot plates of pasta, which they ate voraciously. “Unfortunately, they were not used to that type of food and all had violent diarrhea.”

By early 1943, it became obvious things were not going well for the Italians and their German allies in North Africa. The island was used as a refueling base for German planes bound for North Africa and returning with wounded.

On one of the return flights in April, shortly before the collapse of the Axis armies in Tunisia, a Ju-52 crew gave Ferrara a female German shepherd named Iole. The dog was a pet and was being evacuated by the crew; Ferrara was a familiar face at Pantelleria to transiting aircrews, and the Ju-52 crew thought he could provide a better home for Iole.

By the end of April 1943, ferries and other small craft began appearing at Pantelleria loaded with soldiers that stopped only for refueling before continuing to Sicily. Ferrara observed: “I realized at that time that our happy times as noncombatants was about to end.”

Ferrara was on the roof of his house on Saturday morning, May 8, building a pigeon loft, when he heard the drone of many aircraft and looked up to see the first wave of what would become a 35-day nightmare of aerial attack on the island.

“There were dozens and dozens of aircraft,” he said. “They looked like the dark clouds of a thunderstorm. I could not run away but rather stood there transfixed. They flew over my house and dropped their load of bombs on the airport. From my position, it seemed to be a real volcanic eruption, the bombing was so intense.”

The choice of targeting the airfield instead of the port and town of Pantelleria was a blessing in disguise. If the first bombing raid had targeted the town, Ferrara estimates thousands of people would have perished, but instead it served as a warning. Immediately, people fled the town in droves, seeking refuge in country houses and in the many shelters and tunnels constructed during the military buildup in the 1930s. By the end of the day, the island’s only power plant had been hit, and the inhabitants remained without electricity until the island surrendered on June 11, 1943.

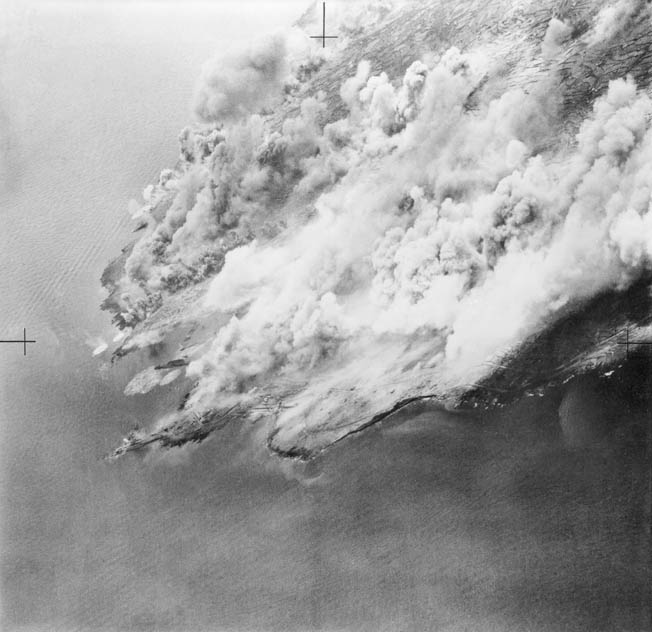

Ferrara was fortunate that his in-laws lived in the country and he was able to move his wife, baby, and Iole there immediately. During the next 35 days of bombing and occasional shelling by the Royal Navy, the Allies made a total of 140 separate raids on the island, and each involved hundreds of aircraft. By June 11, approximately 20,000 tons of explosives had been dropped, for an average of one ton for every civilian man, woman, child, and military member on the island.

Life under such bombardment “was hell.” By the first week of June, the town of Pantelleria did not exist; 95 percent of the buildings in the town had been destroyed or rendered uninhabitable.

Even the dead were not immune from the onslaught. Once, when caught in the open at the beginning of an air raid, Ferrara sought refuge in the town cemetery near his in-laws’ home. A stick of bombs hit the cemetery and disinterred many of the dead. Ferrara relates it was an appalling vision. Graves had been blown open, and bones and decomposing bodies were scattered everywhere.

For the living, their lives were constantly interrupted by the increasing frequency of the bombing raids. Meals were frequently skipped, sleep was difficult, water was rationed, and nerves were frayed.

Even animals on Pantelleria were traumatized by the bombing. Ferrara’s dog Iole began shaking uncontrollably at the first sound of aircraft engines. Yet, for the 20 men under Ferrara’s command, “there was never a complaint or protest. They fulfilled their duty in silence until the last day.”

Despite the intense bombing, casualties on Pantelleria were surprisingly light. The low number of casualties was largely due to the early evacuation of the town of Pantelleria and the extensive usage of bombproof shelters. In fact, the lack of concentrated anti-aircraft fire reported by fighter and bomber crews was largely due to the gunners taking shelter during the raids.

The bombing of Pantelleria had initially been met with only occasional antiaircraft fire and no Axis fighter opposition. By June 1, the German Luftwaffe and Italian Regia Aeronautica fighter aircraft began to contest the Allied air onslaught with fighters based in Sicily. These fighter sweeps consisted of normally no more than 10 planes, although on June 5, a force of 15 or 20 Messerschmitt Me-109s and Focke Wulf FW-190s intercepted a formation of B-25s and P-38s over the island.

The next day, Italian Me-109s appeared; however, the efforts of the Axis pilots seemed halfhearted at best. Attacks were not driven home, and the fighters retired at the earliest opportunity. The intervention of Sicily-based fighters did nothing to blunt the bombing attacks.

In all, by the time of the surrender of the island, the Allies claimed 57 aircraft destroyed, 10 probables, and 21 damaged for the cost of about a dozen Allied aircraft.

The outline for the offensive called for increasing numbers of air attacks on June 8 and 9, with the maximum number of sorties on June 10 and 11 (D-day). The number of aircraft in the skies over Pantelleria during these last days of furious bombardment caused a new danger to the Allied pilots: the danger of mid-air collision.

So many aircraft were targeting the five-by-eight-mile island that pilots sometimes found it necessary to circle to allow the smoke from previous bombs to clear prior to beginning their bomb runs.

With most of the crewmembers’ eyes focused on the island and not outside the aircraft, there were inevitably a number of near misses. It was the top cover of Supermarine Spitfire fighters that became traffic cops for some of these raids. They directed pilots to modify their courses to the targets to reduce the concentration of aircraft over the island and to take new courses to return to base to avoid flying into aircraft that were still on the inbound leg of their bombing missions.

The bombing continued almost nonstop with the exception of a three-hour pause on June 9. During that pause, three volunteer fighter pilots from the 33rd Fighter Group flew their P-40s at low altitude and dropped leaflets on the airfield and port facilities of Pantelleria and the residence of the military governor of the island, Vice Admiral Gino Pavesi, with a surrender ultimatum from Lt. Gen. Spaatz.

The ultimatum called for an immediate cessation of hostilities, unconditional surrender of all armed forces, who would become prisoners of war, and the abandonment of all military installations, which were to be left intact. In case the garrison wished to capitulate, it was directed to display a white cross on the airfield and fly a white flag in the harbor area.

Shortly after the ultimatum leaflets were dropped, thousands more were dropped by B-26s informing the garrison and civilian population that the demand for surrender had been given to Pavesi and underlining the futility of further resistance. The Allies repeated the leaflet drops the next day, June 10. Giuseppe Ferrara recounted that the surrender leaflets were welcomed as the island inhabitants were critically short of toilet paper.

As soon as it was apparent that there was no response to the two surrender demands, final preparations went ahead to embark the British 1st Division for a landing on June 11, 1943; the division loaded their transport ships at the Tunisian ports of Sousse and Sfax on the evening of June 10.

The force was split into three convoys, two fast and one slow, that left in total darkness with the clouds obscuring the moon. The three convoys were scheduled to arrive eight miles from the harbor of Pantelleria at 9:55 am the next day. There the assault force would load into landing craft and, protected by four flak craft, five escorting destroyers, trawlers, and mine sweepers, make for the harbor and land the landing force.

The assault force was well equipped. Every man going ashore carried a mess tin and two days’ rations, a water bottle, water sterilization tablets, a tube of mosquito repellant, two rations of rum (one for reserve and one to be consumed on the go), a first-aid kit, and a pack of cigarettes.

Offshore the division had reserves of four meals a day plus water for a week to include enough for 10,000 prisoners and 15,000 civilians. Corporal John Best, a Royal Marine with the landing force, had some reservations about the chosen date for the invasion. “Finally, came our first invasion. It was to be Pantelleria, off Sicily on 11 June 1943, which was also my 19th birthday.

“It was the custom of our mess that on our birthday the lucky man got ‘sippers’ [rum] all round which, of course, meant that I would be ‘three sheets to the wind.’ I explained to the captain of the ship the situation and asked if the invasion could be postponed for a day; he said quite definitely it could not.”

During the night of June 10/11, a British radio listening post on Malta intercepted communications between the military governor of Pantelleria, Admiral Pavesi, and Supermarina, the headquarters of the Regia Marina. Pavesi explained that the garrison was running short of water and munitions and had been told to surrender.

Supermarina’s reply was short and to the point: “We are convinced that you will inflict the greatest possible damage upon the enemy. Long Live Italy!”

The next morning, despite the heavy bombardment of the town and port of Pantelleria, Pavesi held his normal morning staff meeting. Polling his staff officers, he found the overwhelming majority were in favor of capitulation. Pavesi decided to bypass the chain of command and at 9:50 am sent a message directly to Mussolini advising him of his plan to surrender.

At the same time Pavesi’s message was being sent to Mussolini, the dictator had been briefed by Supermarina that Pavesi was going to hold the island. Il Duce dispatched a message to Pantelleria praising the heroic resistance of the garrison and announced the award of the Cross of Savoia for Admiral Pavesi. However, by 11 am Mussolini had received Pavesi’s message that he was planning to surrender due to water shortages.

No doubt chagrined, Mussolini replied to Pavesi, concurring with his surrender plans and telling the admiral, “Only Stalin or the Mikado [the Japanese Emperor] can order a commander to fight to the last man,” and directing him to inform the British on Malta that he was surrendering due to the lack of water for the civilian population. Mussolini’s permission did not reach Pavesi until he had already surrendered.

At 10:30 am, June 11, the first wave of British landing craft left the invasion fleet en route to the Red, White, and Green landing beaches at the port of Pantelleria, their approach hidden by fog from lookouts on the island. The landing areas were being swept by gunfire from four Royal Navy cruisers and three destroyers while the town was simultaneously being bombed by hundreds of B-17s. This last fusillade of firepower directed against the defenders stopped, according to schedule, at 11:45 as British landing craft approached their landing zones.

Admiral Pavesi’s signal to Malta that he was surrendering was sent at 11 am, simultaneously with his order to raise a white flag in the town and display a white cross on the airfield. Delays in communicating the orders to all the defenders caused some isolated machine-gun fire against the landing craft as they beached, but they were quickly silenced and no Allied casualties were suffered.

Fighters making low-level strafing runs on the island reported seeing the white cross on the airfield, and the order was given to the Royal Navy ships off shore to cease fire. Due to a breakdown in communications, the Mediterranean air forces did not receive the cease-fire order and continued sporadic bombing of targets until late afternoon, an act for which Lt. Gen. Spaatz later apologized.

At noon, 20 soldiers of the 1st Battalion, Duke of Wellington Regiment set foot on European soil for the first time since the Dunkirk evacuation three years and one week earlier. They were greeted by the few Italian soldiers in the vicinity waving white flags. There was no more resistance offered by the beleaguered defenders, and the seizure of the island went off without a hitch, with one exception.

Winston Churchill, in his memoirs, said the only casualty was a British soldier “bitten by a mule.” The unfortunate soldier was Corporal Sanderson of the 2nd Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters, who had actually suffered a fatal kick in the head by a jackass.

The Comando Supremo of the Italian Armed Forces released war bulletin 1113 the next day, stating: “Pantelleria, subjected to massive air and naval actions with a frequency and intensity unprecedented in history, deprived of water resources for the civilian population, was yesterday forced to cease resistance.”

In his report to General Eisenhower, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, wrote: “When we landed, we realized that a garrison animated by another spirit could have continued fighting. The number of enemy killed has been extraordinarily low. In the underground hangars, little was damaged and their equipment was intact. There were still sufficient food and water on the island. What we destroyed was their will to fight.”

For Giuseppe Ferrara, the arrival of British troops meant the beginning of his journey to a prison camp. On the morning of June 11, he was at his post in the underground fuel storage depot near the airfield; his wife and child and dog were in a nearby tunnel. A patrol of about 30 British soldiers appeared at the entrance to his storage depot, and an officer with an Australian accent called out in Neapolitan dialect, “Are you the boss?” “Yes,” Ferrara replied. “How many men do you have?” Twenty was his answer.

“Do you want to go into captivity? We will keep you here, and you can continue to do what you’ve always done. Tell me where there are munitions, fuel, and other material and you can stay working here and be next to your wife.”

Ferrara refused to cooperate, and he and the rest of his men were taken prisoner of “His Britannic Majesty.” He had no time to say goodbye to his family, but days later he saw a photograph in a British military newspaper of a long line of civilians being loaded aboard a transport for return to Italy. In the photo, he was relieved to see his wife and child. The British put him on one of the invasion ships and took him and his fellow prisoners to Tunisia, where they were turned over to the French for custody.

Ferrara recalled that the British were firm but fair captors and treated their prisoners well, but being prisoners of the French was another story. The French relegated the running of their North African POW camps to their colonial troops, the Senegalese. Ferrara described his internment in his postwar memoirs as “hell on earth.” The Italians suffered brutal treatment, inadequate food, lice, and exposure to the elements; many men succumbed to the conditions in captivity.

While at the POW camp at Ben Arous, Ferrara and some other men hatched an escape plan. They broke out of their camp and, while traveling by night and hiding by day, searched for an American Army patrol. After two days they found one and were taken to an American encampment where they were treated to their first showers, dusted with DDT, and given hot food and cigarettes.

Unfortunately, this respite lasted only a month until the French discovered their whereabouts and demanded their return. It was not until February 1946 that Ferrara was finally returned home to Naples and reunited with his family—and Iole.

A British postwar commission investigated the effects of bombing on Pantelleria and discovered that only 36 military and three civilians died during the attacks. Of the 118 guns on the island, only 16 had been destroyed and 43 damaged. The food and water supplies were adequate for prolonged resistance although the distribution system for the water relied on motor transport that was interrupted by the destruction of roads and trails on the island. Admiral Pavesi stated that the water supplies had been contaminated by the bombing, but the inquiry could find no proof of that.

Was Pantelleria’s surrender due solely to the application of airpower? Certainly the unrelenting aerial bombardment weakened the defenders’ will to resist; Hap Arnold’s observation to that effect was accurate. Italy’s German allies certainly expected a stiffer resistance from Italians that were defending their home territory for the first time. They expected Pantelleria to represent a line that could not be crossed, like the Rhine River was for the Germans in 1945. They were disappointed.

For the Italians, Pantelleria was another domino of defeat that began in North Africa. The Italians were faced with the prospect of either losing their independence to the Anglo-Americans or greater subservience to their German allies. In light of these two choices, defeatism spread first through military leadership, then through the ranks, and finally through the Italian population.

For the Germans, it confirmed suspicions that the Italians were unreliable allies and that in the upcoming battle for Italy the Wehrmacht would have to take increasing responsibility for her defense.

The fall of Pantelleria had other wide-ranging effects. Besides removing a threat to the Allied invasion of Sicily and furthering the collapse of Italian morale, Hitler was forced to postpone his upcoming Kursk offensive in Russia—Operation Citadel—due to his fears of an imminent Allied invasion in the south of France.

For the Allies, Operation Corkscrew was an unqualified success. Pantelleria had been seized from the enemy at little cost. Admiral Pavesi surrendered the garrison and all the supporting equipment and infrastructure intact. Within a week, the airfield runway was open, and a P-40 fighter group based on the island flew top cover for the invasion of Sicily the next month.

For the first time, air power had been able to fulfill the dreams of Giulio Douhet, Billy Mitchell, and Alexander de Seversky and compel an enemy to surrender without the need to seize territory by land forces.

By concentrating overwhelming power on a narrow front, aerial bombardment had reduced a seemingly impregnable fortress on its own. Unfortunately, the other consequence of the bombing of Pantelleria reinforced the mistaken belief that dropping large numbers of bombs on enemy positions would make land movements easy.

RAF Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder knew better. He wrote, “Pantelleria is becoming a perfect curse.” The “curse” was the idea that air power alone had replaced land forces as the war winner of the future. The fact remained that air power continued to be a blunt instrument. Thousands of tons of bombs would need to be dropped to achieve strategic effect.

It was not until half a century later that the promise of air power first revealed at Pantelleria was finally realized. From March to June 1999, NATO air power in Operation Allied Force caused Slobodan Milosevic to withdraw Serbian forces from Kosovo after 38 days of intensive bombing with precision munitions.

Generals Arnold, Spaatz, and Doolittle would have been proud.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments