By Robert Barr Smith

Private Henry Tandey had a clear shot at the German soldier. He was so close that he could look his enemy in the eyes. Tandey could not have missed. But the man was wounded; one account of that far away day in 1918 says that the German was lying bleeding on the ground. In any case, the German soldier made no move to resist; he simply stared at the Englishman. Tandey eased off the trigger of his Enfield and did not fire. “I took aim,” said Tandey later, “but couldn’t shoot a wounded man. So I let him go.”

Maybe he shouldn’t have.

The German soldier went on his way, and Tandey went his. No doubt the Englishman forgot all about the man he had spared, because Tandey still had a war to fight. And not long afterward, Tandey got the welcome news that he had been awarded his nation’s highest medal for gallantry, the Victoria Cross (VC). He would receive his cross at Buckingham Palace in December 1919, at the hands of King George V himself.

Tandey won the VC near a French town called Marcoing, which lay about seven kilometers southwest of Cambrai, on September 28, 1918, when his company was held up by heavy German machine-gun fire. Tandey crawled forward, leading a Lewis Gun team, and knocked out the German position. He then pushed on to the Schelde Canal, a broad embanked stream. Some small British elements had crossed the canal on a set of lock gates and a wrecked railway bridge, but more troops were needed quickly on the other bank.

However, as German resistance stiffened, the canal obstructed his unit’s advance, and Tandey reached the bank of the canal to find an impassable break in the planking of a bridge spanning 50 yards of water. Tandey worked under heavy fire to cover the gap in the bridge with planks and open the way for the rest of his unit to cross.

In ferocious fighting later the same day, Tandey and eight other men were cut off behind German lines. Vastly outnumbered, Tandey still led his handful in a wild bayonet charge that smashed into the Germans and drove them back against the rest of Tandey’s unit, which took 37 prisoners. Wounded twice, Tandey went on to lead his men in a search of dugouts, winkling out and capturing more than 20 additional Germans. Only then would Tandey stand down and get his wounds dressed. Badly hurt, for the third time in the war, he was on his way to a hospital in England.

Tandey was born in 1891, in Leamington, Warwickshire. The son of a stonemason who had also soldiered for Britain, he became a professional soldier, a tough, long-service infantryman who survived four years of bitter war in Belgium and France. Nicknamed “Napper,” Tandey was not a large man, standing less than five feet, six inches, and weighing just under 120 pounds. But what he lacked in stature, Napper Tandey made up in grit and high courage.

Back in 1910, he had enlisted in Alexandra, Princess of Wale’s Own Yorkshire Regiment, commonly known as the Green Howards. Beginning life as the 19th Regiment of Foot, the Green Howards were a famous outfit named for the color of their uniform facings and the name of their first colonel. It distinguished them from another famous regiment commanded by a different Howard, which wore buff-colored facings. During the war, that regiment would win its own fame simply as the Buffs, the East Kent Regiment.

Tandey had served with the 2nd Battalion of the Green Howards in South Africa and on the island of Guernsey before the war. He was a tough, able soldier, and by the time of his exploit at Marcoing he had already been five times “mentioned in despatches,” a peculiarly British means of honoring high achievement under fire. He had also won the Distinguished Conduct Medal while commanding a bombing party. On that occasion, he rushed a German post with just two soldiers to help him, killing several of the enemy and capturing 20 more.

Tandey also held the Military Medal for heroism under fire. This decoration he won at a place called Havricourt in the fall of 1918, where he carried a wounded man to safety under heavy fire and organized a party to bring in still more wounded. Then, again in command of a bombing party, he met and broke a strong German attack, driving the enemy back, as his citation read, “in confusion.”

He had been wounded on the bloody Somme in 1916 and shipped back to England to recover. Once on his feet again, he joined the 9th Battalion of the Green Howards, with which he was again shot up at Passchendaele in the fall of 1917. After some time in the hospital in England, it was back to France, this time with the 12th Battalion of the regiment. When the 12th Battalion was disbanded in July 1918, Tandey was attached to the 5th Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment, and it was with this outfit that he won his VC.

After the war, Tandey soldiered on with the 2nd Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s, serving in Gibraltar, Turkey, and Egypt. In 1920 he was one of 50 VC holders who served as a guard of honor inside Westminster Abbey during the ceremonial burial of Britain’s Unknown Soldier.

In January 1926, he was discharged as a sergeant, at that time the most heavily decorated enlisted man in the British Army. He spent the next 38 years in his home town of Leamington, where he married and worked as a “commissionaire” or security man for Standard Motor Company. A modest, quiet man, he talked little about the war.

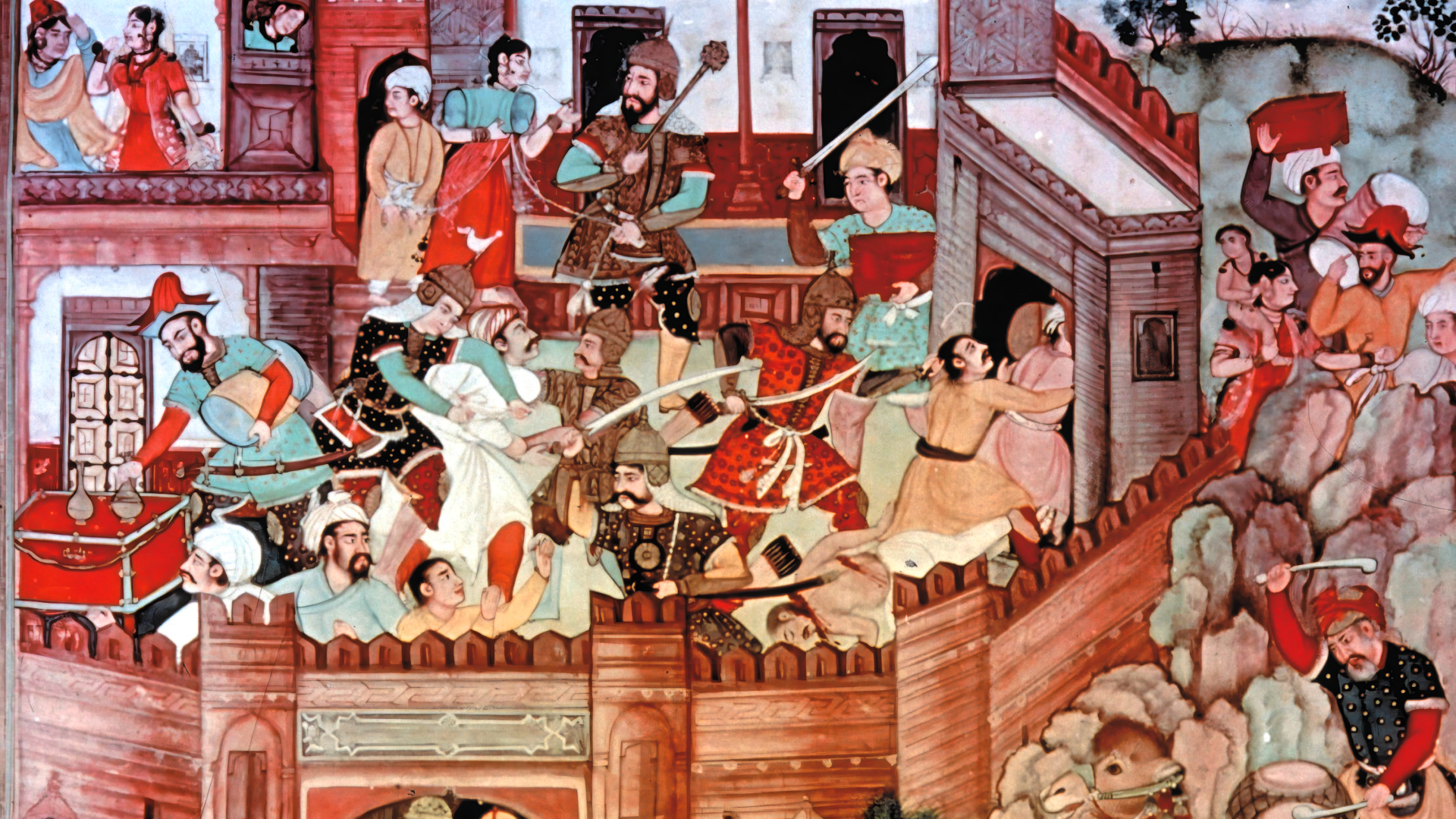

With his fighting days well behind him, Tandey’s war should have been over. But it wasn’t. About the time of the award of his VC, a painting appeared, a graphic image of war by Italian artist and illustrator Fortunino Matania. Matania had included Tandey in his painting of soldiers at the Menin Cross Roads in 1914, not far from the battered Flemish town of Ypres. Tandey is facing the viewer, carrying a wounded soldier on his back, and the painting also shows other men of the Green Howards and a wounded German prisoner.

Matania’s vivid painting became something far more than a picture, all because of the man who acquired a copy of it. For in 1938, then British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain made his futile attempt to guarantee “peace in our time.” Flying to Germany to meet Hitler in the Alps, he was entertained at the Eagle’s Nest, perched on the Kehlstein Rock high above the town of Berchtesgaden. And there, displayed on a wall of that ostentatious aerie, was a copy of Matania’s painting. It was a curious choice of art for Hitler since it showed only British troops, but Hitler soon explained.

Hitler pointed to Tandey, commenting to Chamberlain, “That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again, providence saved me from such devilishly accurate fire as those English boys were aiming at us.”

Then Hitler went a step further. I want you to pass on my best wishes and thanks to the soldier in that painting, he said, and Chamberlain replied that he would contact the man when he returned to England. The prime minster was as good as his word. Only then did Tandey find out that the pitiful wounded man he had spared, the bedraggled German corporal in the Bavarian 16th Reserve Infantry Regiment, was now the chancellor of Germany, on his way to becoming the ogre of Europe.

Tandey’s relatives remembered the telephone call from Chamberlain. When Tandey returned from talking to the prime minister, he related the tale of Chamberlain seeing the painting. The prime minister told him, he said, that Hitler had pointed to Tandey’s picture and said, “That’s the man who nearly shot me.”

Now Hitler probably would have known the name of the British soldier who spared his life. For the copy of the Matania painting on his wall at the Adlerhorst had come to Berchtesgaden from the British Army about 1937. Colonel M. Earle, an officer of the Grenadier Guards, had furnished the copy through a most unlikely intermediary, a German doctor then resident in Siam.

Earle had commanded the first battalion of the Grenadiers, and his unit had been in the line next to the Green Howards during the bitter fighting around the Menin Cross Roads. Badly wounded and captured at the end of October 1914, he was treated by a young German doctor named Schwend, whom Earle believed had saved his life. Schwend contacted Colonel Earle in the mid-1930s through a British lawyer also living in Bangkok, and he and Earle carried on a continuing correspondence.

In his letters to Earle the doctor remembered the terrible losses his unit suffered from the murderous British rifle fire in the Ypres area. “There is no doubt,” the doctor wrote to the colonel, “that at the beginning of the war the British army was greatly under estimated….You will find in all the personal and official reports of our Division what a bad shock to our morale it was for our troops to find out in the very first days that the enemy was really superior to us in fighting experience…. We had the most severe losses for days and days, and most of our men had not seen the enemy…. I have seen some of those young volunteers crying in despair that they were shot down from ‘nowhere,’ and that they had not seen an Englishman.”

And in passing, Schwend also commented that Hitler’s unit had been fighting in the German line directly opposite the Green Howards.

Earle, feeling a deep sense of obligation to the German who had fought for his life near the Menin Cross Roads, pondered the Matania painting. “It occurred to me,” he wrote in the Green Howards Gazette, “that if I could obtain a copy for Dr. Schwend it might compensate him for not having been able to see the Green Howards in the flesh 22 years ago.”

Earle sent the copy of the painting to Schwend, who thanked him profusely in a letter dated January 8, 1937. The colonel and the doctor would later stand together by the Menin Gate, on which are inscribed the names of 56,000 British dead, listening to a bugler play the last post in the gathering dusk.

Some time after Earle sent his gift to the doctor, the photo made its way to Berchtesgaden, to the Adlerhorst high on Kehlstein Rock. One of Hitler’s adjutants wrote to Earle in thanks. This officer—called in one source Captain Weidman—was surely Captain Fritz Wiedemann, Hitler’s superior officer in World War I. Wiedemann served as Hitler’s Army adjutant from 1937 on—der Führer had one from each service—until Wiedemann was fired four years later for disagreeing with Hitler once too often. This is what Wiedemann wrote, here in translation: “I beg to acknowledge your friendly gift … sent to Berlin through the good offices of Dr. Schwend. The Führer is naturally very interested in things connected with his own war experiences, and he was obviously moved when I showed him the picture and explained the thought which you had in causing it to be sent to him. He has directed me to send you his best thanks for your friendly gift which is so rich in memories.”

Surely a painting of British troops would not arouse such excitement in Hitler for its own sake. Nor would he have been so pleased to have a copy unless it meant something very special to him. There was plenty of excellent and graphic war art available, paintings and photographs showing German troops in action, copies of which Hitler could have easily had in Germany, simply for the asking. And if the story of his comment to Neville Chamberlain is true, the German chancellor recognized Tandey as a man who had spared his life.

The story of Tandey and Hitler first appeared in the British tabloid newspaper Sunday Graphic in December 1940, and has been the subject of some controversy since. Inevitably, there have been questions raised whether the battlefield meeting of Tandey and Hitler ever happened at all. There appears to be some evidence that Hitler was on leave when his unit and Tandey’s fought in the Marcoing sector. Moreover, at least one knowledgeable writer tells that Hitler’s unit was not close to Marcoing at the time Tandey won his VC.

It has also been suggested that the meeting, if in fact it occurred, might well have happened during the Ypres fighting in 1914, for that is the time portrayed in the Matania painting that Hitler admired. Tandey might indeed have spared Hitler during the Battle of First Ypres, for he later told journalists that he had on occasion held his fire to spare wounded German soldiers before the Marcoing fighting in 1918.

One writer speculates that the whole legend may be “purely a Hitler-based story,” since Hitler held the British soldier in high esteem. He might also have wanted to butter up the British prime minister with flattering remarks about the British Army. And Hitler might have transposed the British soldier who spared his life into Tandey, intentionally or otherwise. Maybe so.

And certainly skepticism is natural, for the element of coincidence in this story is almost too good to be true. But not quite. While many German records of World War I were later destroyed in the bombings of World War II, there is no dispute that both Tandey’s battalion of the Green Howards and Hitler’s unit—the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment—were present in the fighting around Ypres in 1914 and Hitler was wounded in that area. Moreover, Dr. Schwend remembered that the 16th Bavarians fought opposite the Green Howards at the Menin Cross Roads and were in action there on October 29.

It is also significant that Tandey believed the story—for the rest of his days he was haunted by the thought that his merciful gesture might have cost the world untold misery and millions of wanton murders. This compassionate man could not forget what might have been avoided had he squeezed his trigger and shot down that wounded German.

Tandey was living in Coventry during the Luftwaffe’s terrible attack on the city in November 1940. His own home was destroyed by German bombs, curiously leaving intact only a memorial clock given to him by the Old Contemptibles Association, a group of veterans of the First British Expeditionary Force that served during August-November 1914. On that same dreadful night the Luftwaffe destroyed Coventry Cathedral.

Tandey saw firsthand the resulting destruction, misery, and death and he worked with others to help pull survivors from the rubble of the city. He is said to have told a journalist at about that time, “If only I had known what he would turn out to be. When I saw all the people, women and children he had killed and wounded I was sorry to God I let him go.”

Henry Tandey would return to duty during World War II as a recruiting sergeant after doctors rejected him for active service on the basis of his old wounds. On the 60th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, he shared the reviewing stand during a Leamington parade honoring the men who had fought along that bloody river. A little more than a year later, he passed away in Coventry at the age of 86. Although Tandey had specified that his funeral was to be private, it was nevertheless attended by the mayors of both Leamington and Coventry.

Tandey lies today in Marcoing’s British Cemetery. He was cremated and wished to have his ashes scattered across the Marcoing battlefield. But because of French restrictions prohibiting such things, his ashes were put to rest among the remains of British soldiers who were killed in action and buried in the Marcoing British Cemetery.

In later days his decorations were sold by his widow for a hefty 27,000 pounds, but it is pleasant to relate that they were later acquired and presented to the Green Howards by a patriot and great friend of the regiment, Sir Ernest Harrison, OBE. Tandey’s medals reside today in the regimental museum in the city of Richmond, Yorkshire. He is also commemorated in an unusual way, one which he probably would have liked. There is a Tandey Bar in the Royal Hotel, Royal Leamington Spa, and for years there was a VC Lounge in Leamington’s Regent Hotel, where Tandey had worked before his enlistment in 1910.

For many years Tandey’s old regiment, the Green Howards, was one of the few units unaffected by the perpetual reorganizations and amalgamations imposed by British governments. And then, in 2004, during still another reorganization, the Green Howards became part of the new Yorkshire Regiment, sharing that distinction not only with The Prince of Wales’ Own Regiment of Yorkshire, but also with the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment.

The new outfit shares the gallantry of Private Henry Tandey. He will not be forgotten.

Parallel experience in 1777 when Capt. (later Maj) Ferguson refused to take a clear shot a George Washington since his back was turned. Such are the hinges on which history swings.