By Kevin M. Hymel

On a Belgian hillside at the height of the Battle of the Bulge, an American lieutenant watched as a jeep carrying four men dressed in American uniforms stopped on the road in front of him. Two of the men dismounted and approached, neither showing any rank on their uniforms. A cold drizzle kept everything miserable.

“I’m Captain Remple, Military Intelligence,” one of the men informed the lieutenant. “Give me a briefing of the situation.” The lieutenant, suspicious of the strangers, looked them up and down.

“You know,” the lieutenant explained as his men gathered around the strangers, “we just got a word that Germans were coming this way in American uniforms, and you guys look just like them.” With that, he started a line of questioning: “What’s the fifth general order?” The captain didn’t know. “Who won the World Series?” again, the captain didn’t know. “Recite the Star Spangled Banner.” The captain started to speak the tune, but when he got to “by the dawn’s early…” He stopped. He could not remember the rest. The man next to the captain just stood there silently. Just then, a third man from the jeep came running up carrying his rifle and shouted “Vat goes on here?”

That’s all the lieutenant and his men needed. They lowered their rifles and jabbed the barrels into each of the three men’s abdomens. Other soldiers ran down to the jeep and pointed rifles at the driver.

For seven hours the soldiers questioned their new prisoners outside in the cold. When they asked the man who quietly stood next to the captain where he was from, he answered in perfect English, “Yeah, I’m from Germany.” Even though he had no German accent, the men remained suspicious.

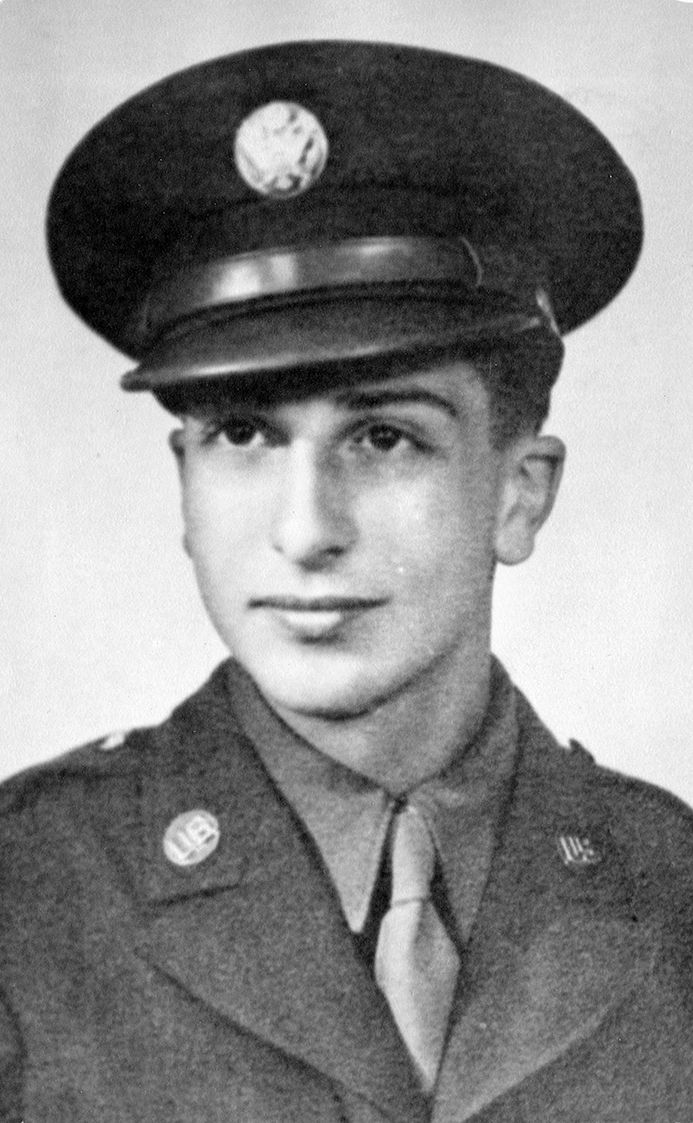

The quiet man from Germany was Frank Cohn, a Jew who had emigrated to the United States in 1938, became an American citizen, and was serving as an interpreter for a prisoner interrogation team attached to Lieutenant General Omar Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group, but he failed to convince the lieutenant that he was anything more than a German spy.

Four years earlier, 16-year-old Cohn was growing up in New York City when he learned the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He had been in the United States for almost three years. He and his parents had arrived on visitor visas, but 10 days after he and his mother united with his father in the city, back home in Germany Nazis ransacked Jewish businesses, synagogues, and facilities and imprisoned Jewish males in concentration camps—Kristallnacht. Fortunately, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order that Germans visiting the United States could remain indefinitely.

Cohn enjoyed his new home and the friends he made. One day, while playing ping-pong with a buddy, they met two girls. They called one “Ping” and the other “Pong.” Pong’s name was Pauline Brimberg. Cohn called her Paula and they dated for a while.

In September of 1943, the U.S. Army drafted Cohn a month after his 18th birthday. He reported to Fort Dix, New Jersey, where he received his uniform, worked on Kitchen Patrol (KP) duty, and watched two movies: one on why the United States was at war and the other on how to avoid venereal diseases. “After that,” he recalled, “I always volunteered for guard duty to avoid KP.”

On his fourth day, all the draftees but him departed for basic training. When he asked his sergeant, a Native American named Cheraux, what had happened, Cheraux responded, “Quite simply, you’re an enemy alien,” and reminded Cohn that he held a German passport. Cohn figured he would spend the rest of his Army career pulling KP.

But Cohn had joined Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) in high school and participated in a semester of ROTC at the City College of New York. “I have some military background,” he told Cheraux. “I know close order drill, I know firing of weapons, I know some tactics.” Cheraux considered his young recruit’s offer and told him, “I’m going to make you an acting gadget.” Cohn had no idea what that meant. Cheraux handed him an armband with corporal stripes. His new job was to escort recruits to watch the two movies. “It was so much better than KP!” remembered Cohn. “I’ve seen that movie about avoiding VD more than anyone in the Army.” He never got the disease while he served.

Finally, after three months, Cohn received orders to report to Fort Benning (now Fort Moore), Georgia, for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which, after basic training, sent recruits to colleges to earn degrees in fields like medicine, engineering, and foreign languages. But before Cohn could complete his training, the Army canceled the program. Soldiers, not scholars, were needed to win the war.

The Army then sent Cohn to Columbus, Georgia, where he was officially sworn in as an American citizen. “I was no longer an enemy alien!” he said. From there he went to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to join the 87th Infantry Division.

It was at Fort Jackson that Cohn received his first injury. During a gas mask demonstration, one of his sergeants tossed what he thought was a smoke grenade among the men, but it was actually a white phosphorus grenade, which burns skin when exposed to oxygen. Cohn raced to the infirmary with his ears and hands burning. The doctors didn’t know how to treat him until the sergeant ran in and shouted, “White phosphorus!” The doctors immediately put Cohn’s hands in two buckets of water. He spent a month in the hospital recovering.

Cohn shipped out to England as a replacement onboard the luxury liner RMS Queen Mary, which had been converted into a troop ship. He spent most of his time on guard duty to avoid KP. Fortunately, guards were allowed to jump ahead of the chow line and were given more spacious accommodations than the rest of the troops.

The Queen Mary steamed into Southampton, England, in September of 1944 and Cohn waited almost a month before boarding a Liberty ship bound for Utah Beach, France. Arriving at a floating dock, he marched onto the beach without getting his feet wet. He could see smashed weapons, jeeps, and armored vehicles all around. “No one said a word,” he recalled. “It was obvious that this was a slaughter.”

Cohn then boarded a train which took him all over France and Belgium until he received orders for Le Vesinet, France, near Paris, to work as an intelligence agent. He reported to a chateau with a handful of other interpreters for a two-week course on German military ranks and Nazi agencies. “I should have been part of the Ritchie Boys [Jewish intelligence soldiers],” recalled Cohn, “but ASTP sent me the other way.”

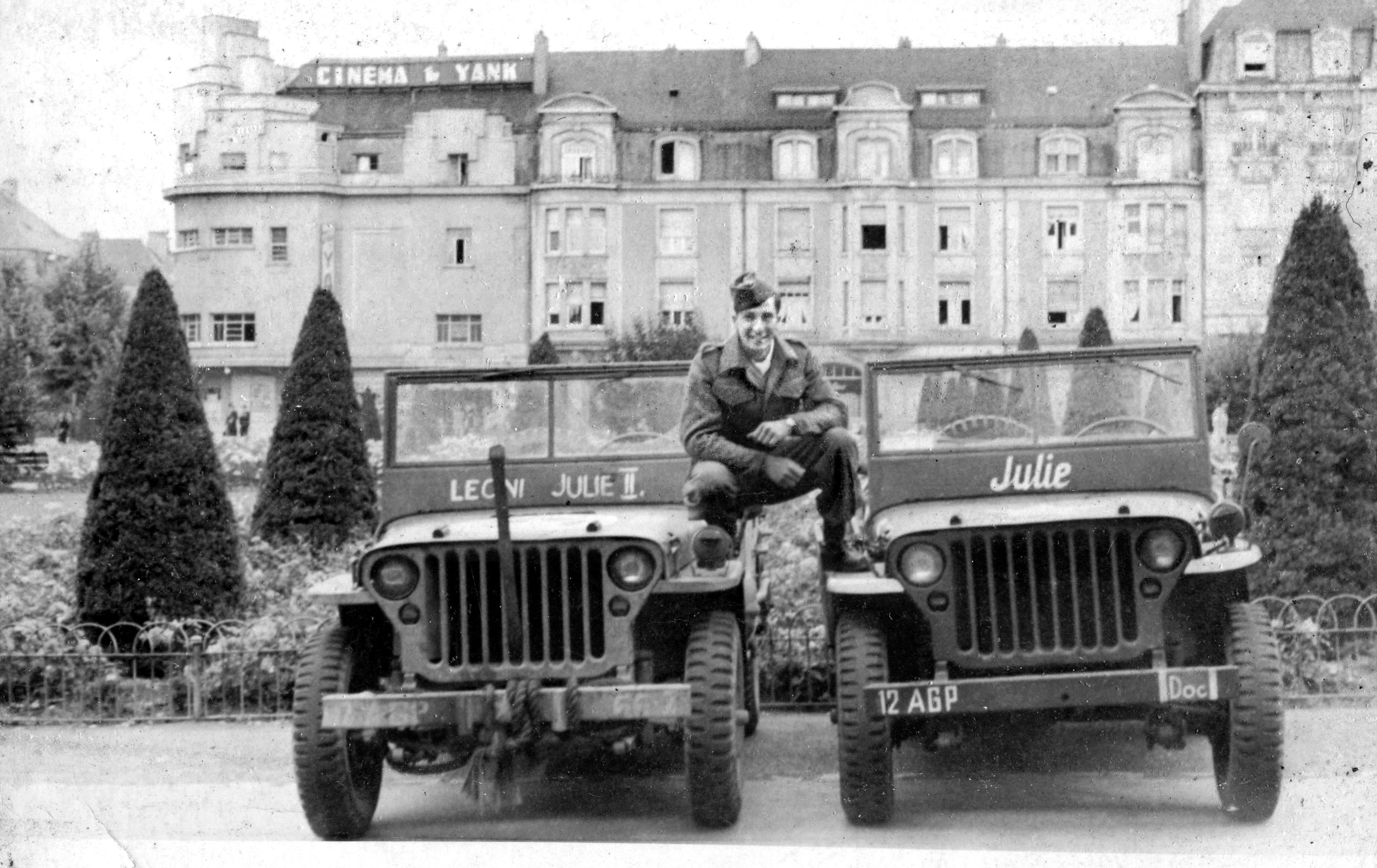

Cohn became a member of Interrogator of Prisoner of War (IPW) Team 66, part of T-Force, which secured German scientific and industrial technology and reported directly to Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group. The six-man team consisted of a captain, a lieutenant, two interpreters, a non-commissioned officer, and a driver. Cohn could only remember the captain’s last name—Remple—the same for the lieutenant—Hershey. Cohn’s other interpreter was a German farmer named Lawrence Froehlich, whom Cohn called “Floh.” As an IPW team, the officers and interpreters wore no rank. The new team headed off to Luxembourg City to meet up with other T-Force units.

The team spent only one night in Luxembourg City before heading off to Remouchamps, Belgium, where the locals offered up their homes to the Americans. Without any orders, the men had nothing to do. “It was very easy,” admitted Cohn, “those first days of December.”

Cohn spent his time visiting with the locals. On a sojourn to Malmedy, some girls invited him and Floh into their home where they shared some family photos. One picture showed their father in a German uniform. “I was in the home of the enemy!” Cohn recalled. They quickly departed and hitched a ride on an Army truck filled with unexploded bombs. Halfway back to their headquarters, MPs stopped the truck and told them that the Germans had broken through the line. The Battle of the Bulge—Adolf Hitler’s major offensive against the American Army in Belgium and Luxembourg—had begun.

Back in Remouchamps, Cohn and his team were alerted to move out but needed time to organize the move. Cohn was ordered to head out in the dark and guard a road against German attack. Rumors spread that German parachutists in American uniforms were working behind the lines. Armed with a rifle and a flashlight, Cohn headed out into the cold to check the password of anyone heading west. “It was the scariest night of my life,” he confessed.

Cohn could hear gunfire all around. A vehicle rolled up and stopped. “What the heck are you doing here?” a GI in the vehicle asked. “I’m making sure you’re not German,” Cohn responded. “If I was a German,” the GI snapped back, “you’d be dead!” The GI told Cohn to get some cover in a roadside ditch. Cohn manned the ditch, but when another vehicle rolled up he shouted “Halt! Halt!” and the vehicle just raced past him. “I’m not doing my job,” he thought.

Around midnight, Cohn and his unit finally headed west. The column moved at only about five miles an hour so no one would get lost. All the vehicles had blackout lights, covers over the headlights that only revealed a slit of light. In Namur, they received orders to circulate through the town looking for Germans disguised as American GIs. “It was miserable,” recalled Cohn, who sat in the back of the jeep as snow, sleet, and freezing rain pelted him. To shield himself from the wind, he huddled in the back seat, using Captain Remple in the front seat as a windbreak.

In the town of Dinant, they came across four dead Germans dressed as GIs in an American jeep who had just been killed by a bazooka blast. They searched the bodies and found dog tags, maps, and explosives. “You could tell they were Germans by their haircuts,” said Cohn. “The GIs must have found out they didn’t have the password.”

The next day, Cohn headed out with Captain Remple, Floh, and their driver for another patrol but got lost. When they passed an American unit deployed on a hillside, Cohn and Floh convinced Remple to ask the lieutenant in charge where they were. Remple agreed and took Cohn with him. Cohn expected Remple to simply ask the lieutenant where they were. Instead, he told the lieutenant, “I’m Captain Remple, Military Intelligence, give me a briefing of the situation,” which led to all four getting rifle muzzles shoved in their guts.

After a few phone calls, the lieutenant discovered they were who they said they were. “Get the hell out of here,” he told them. As they drove back to headquarters, the captain told the team, “I don’t want anyone to say a word of this to anyone.” But when they reached their headquarters in Namur, intelligence soldiers ran up the jeep shouting “Vat goes on here?!?” The word had already spread.

With Christmas came clear skies, allowing Allied airpower to help stem and push back the German tide. Cohn’s team cheered every time aircraft flew over. Team 66 transferred to a small town outside of Liege. “We were there for months,” said Cohn, “waiting for the infantry to get into Germany.” It was in Liege that Cohn took his first shower in weeks. He stood under the warm spray for 20 minutes, washing away the accumulated grime. When other soldiers screamed at him to get out, he refused. “I wouldn’t move.”

On March 7, 1945, the American First Army captured the German city of Cologne. Team 66 headed to the city, passing GIs looting everything they could get their hands on. “This is terrible,” Remple told Cohn as they passed soldiers sporting top hats. “Our army shouldn’t act like that.” Most of Cologne had been reduced to rubble but the men could see the city’s famous cathedral still standing. Fighting continued in the city.

Team 66 hunted for enemy personnel and building targets. The personnel were interrogated for information while the buildings were assessed for future use in prosecuting war criminals. The team took over an apartment building, kicking out the German civilian residents. Floh opened a window and started playing German songs on an accordion. Germans on the other side of the street opened their window and listened. Floh then addressed them, pretending to be Adolf Hitler. “Comrades of the people,” he started, “you get rumors that we didn’t get any coffee, well, we have plenty of coffee but the reason you don’t get any coffee is because we can’t get to it, because there’s too much butter in front of it.” The Germans slammed their window. Cohn and Floh burst out laughing and Cohn translated Floh’s dialogue to the rest of the team so they could share in the joke.

A few days later, the team checked out a German military barracks on the west bank of the Rhine River, the last natural barrier for the Allies attacking into Germany. Cohn and his driver could see German soldiers fleeing so they decided to park at a distance and proceed on foot. They found only a canary in the building. As they admired the bird, an enemy mortar round exploded near them. The two men took off, knowing the Germans were finding their range from across the river. As they reached the jeep the next mortar came in short. They took off as the third mortar exploded exactly where the jeep had been. “That changed my attitude about the war,” said Cohn. “They’re really trying to kill me.”

Later, on another patrol through Cologne, Cohn and his driver spotted a person in the distance and gave chase. The suspect turned out to be a 17-year-old girl. Cohn started talking to her and the girl was aghast that an American spoke German. When Cohn asked her what she was doing out after curfew, she told him she hadn’t eaten in two days and was looking for food, adding that she and another girl lived with a Dutch woman who had one ration card for the three of them. When Cohn asked her why three people only had one ration card, she explained, “Because we’re Jewish.” “I almost fell out of the jeep,” recalled Cohn.

Cohn and the driver took her home where she introduced them to the Dutch woman. The team gave them their C-rations and the women ate. “It was a pleasure to see them eating our rations,” said Cohn. The Dutch woman explained that she had taken the Jewish girls into her home to protect them from the Nazis but she was dying from cancer and worried what would happen to the girls after she passed. “If I’m gone, they’re done for,” she explained. Cohn headed back to headquarters and told Lieutenant Levy, who was also Jewish, about the situation. “Don’t worry about it,” Levy said, “I’ll take care of them.”

A few days later, Cohn and Floh returned to check on the three women, but were stopped by an “Off Limits” sign on her street. They went back to Levy and asked him why he had put up the sign. Levy didn’t know what they were talking about, so the three went back to the house where they were greeted as liberators. When Levy asked the Dutch woman about the sign, she told him he had done too good of a job. Levy had sent a truck full of food to the house, but when the story got out, other GIs did the same. Truck after truck arrived at the house, packed with food. She went outside and asked a captain how to stop the flood of food. The captain put up the sign. “That Dutch Lady was a hero” said Cohn, reflecting on the incident. “I should have enrolled her in the Yad Vashem as one of those Righteous Among Nations.”

On March 7, elements of the 9th Armored Division captured the Ludendorff Bridge across the Rhine River at Remagen. Cohn and his team waited for hours in a holding area, waiting to cross. When it was finally their turn, they drove the single lane across the damaged bridge. Cohn watched as engineers constructed a pontoon bridge parallel to it. It was a smart engineering move since 10 days after its capture, the Ludendorff bridge collapsed into the river.

On the east bank of the Rhine, Cohn and his team headed north to Düsseldorf, where confused fighting continued. Cohn and Floh drove into the destroyed city and saw white sheets hanging from every building. Civilians who were dismantling a roadblock fled at the sight of the Americans. As Cohn and Floh drove through the roadblock one of their tires blew out. They found a gas station where the owner put on a spare and told them they were the first Americans he had seen. “We’re liberating Düsseldorf,” Floh told Cohn. “It’s not our job,” Cohn snapped back. “Let’s get the hell out of here.” They raced back to headquarters where Captain Remple told them to wait another day before returning.

Cohn returned the next day with a Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) economist. They entered a German steel company building but could only find a janitor. Cohn asked him to gather the company’s directors and the janitor complied. The Americans left and when they returned were escorted into a beautiful conference room filled with German civilians in suits. They offered Cohn a cigar but he begged off. When the CIC agent told them he needed an assets report in 24 hours, they told him they needed six months. The agent said they could have 48 hours. They provided him with the report on time.

A few days later Cohn and Floh were surprised to find an operational telephone exchange building, with German women connecting calls. “Connect me with Berlin,” Floh told one of the women. Once an operator picked up, he asked, “How’s the weather in Berlin?” and started chatting. After a little while he asked, “Do you know who you’re talking to? I’m an American!” The line went dead. “Floh was always a jokester,” explained Cohn.

On patrol in the Ruhr city of Siegen, Cohn heard a screaming woman. He came to find a Polish worker pointing a rifle at a family, including the woman and child. The Pole told Cohn the father was a guard at his work farm. The father claimed he was a railroad official. Cohn asked the father for his papers but the man said he didn’t have any. Realizing the Pole was drunk, Cohn traded him a pack of cigarettes for his rifle. He told the Germans to get out of there. “Our job was to keep order,” Cohn explained. He had saved the German man’s life. “I hope he deserved it.”

On another night patrol, Cohn heard the crunching sound of hobnailed boots on a street. He got out of the jeep and called out “Abteilung halt!” From the darkness, a German noncommissioned officer approached. Cohn asked him what kind of unit they were and the man responded, Volkssturm, Hitler’s last reserves made up of young boys and old men. “I want to surrender myself to you,” the NCO told Cohn, “but we left all our weapons in the forest.”

The NCO had about 50 soldiers with him, which Cohn and his team marched to a POW camp. Upon arrival, a lieutenant in charge told Cohn the camp could not take new prisoners and to try another camp three miles down the road. “What the hell did I get myself into?” Cohn asked himself. As he and his prisoners reached the second camp, he shouted to a guard that a platoon of Volkssturm were heading to the camp and to take care of them. Without waiting for an answer, Cohn’s driver turned the jeep around and they raced off.

Cohn’s team headed for Frankfort to ensure the IG Farben building was suitable as General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s new headquarters. But once they reached the center of the city, they were ordered to a hotel across from the city’s train station to interrogate German officer prisoners to see if any needed further interrogation. Most were quickly sent to POW camps. A Waffen-SS major general stepped up to Cohn, not knowing he was reporting to a Jewish PFC. Cohn asked him his name and he responded, “August Wilhelm von Hohenzollern.” Cohn immediately recognized him from his lessons in Germany. “Oh my God!” he thought, “It’s Prince Auwi, the son of the Kaiser!” Kaiser Wilhelm had been Germany’s last monarch, having been deposed at the end of World War I. “Stay right there!” Cohn ordered, and reported to Captain Ruble, “I got a big one for you.”

His interrogations over, Cohn and his team reached the IG Farben building. It was in shambles. Although the U.S. Army Air Forces had not bombed the building, it succumbed to a different fate. A group of Russian and Polish forced laborers, who had been put into the building by American infantry, took out their rage at the Germans by ransacking the place. They smashed windows and threw furniture out of the building. American engineers added to the destruction by blowing the safes in the basement, finding documents relating to war crimes (the company provided Zyklon B poison to concentration camps) as well as diamonds and German currency. Cohn handed out stacks of cash to his friends as souvenirs, not realizing it had kept its value. “I gave away thousands of dollars,” he said with a smile, “and I never got a single piece of it.” To this day, he believes that if his team had not been pulled away to screen prisoners, they would have stopped the building’s destruction.

Next, Cohn’s team entered a labor camp in Wiesbaden, where they found a complicated situation. Half of the workers were Ukrainian volunteers, while the other half were Ukrainian, Polish, and Russian forced laborers. Cohn found it impossible to figure out who was who since they all only spoke broken German and kept accusing each other of being pro-Nazi. Finally, the team gave up and called everyone forced laborers. Years later, Cohn found out that when forced laborers returned to the Soviet Union, they were all declared volunteers—basically, traitors to the Motherland. The men were imprisoned and the women’s heads were shaved.

On April 12, President Roosevelt died. Cohn cried at the news. The president had been a father figure to him. “He saved me,” said Cohn as his voice choked with emotion, referring to Roosevelt’s executive order that allowed him to stay in the United States after Kristallnacht. “It still gets to me today.”

About two weeks later, Cohn’s team drove the German Autobahn into Magdeburg, along the Elbe River. As they drove, hungry German soldiers ran towards them, surrendering. The war was almost over. The Allies had designated the Elbe River as the delineation line between Soviet and Western Allied forces. Magdeburg lay in the designated Soviet zone. Captain Remple had orders to cross the river, find Soviets commanders, and tell them they could have the city in a few months, once the Americans pulled out. Unable to find an interpreter who spoke Russian, Remple picked Cohn. “I can’t help you,” Cohn protested. “I only speak one word of Russian—‘tovarish (friend)!’” Remple didn’t care.

The two men found a small boat and a German to take them across the Elbe. On the far bank they could see Soviet soldiers. About halfway across the river, Remple stood up in the boat and the Soviets cheered. Upon reaching the west bank Cohn and Remple were hugged and kissed and given vodka. Cohn took his first slug of vodka and realized it was too powerful for him. Then the Soviets hoisted the two Americans onto their shoulders and carried them around to cheers and laughter.

Captain Remple headed off to confer with Soviet officials while Cohn, with his one word of Russian, passed out cigarettes. He found himself sitting along the river next to a Russian sergeant. “Me Moscow,” explained the sergeant. “Me New York,” Cohn told him. “You come visit Moscow,” the sergeant invited Cohn. “You come visit New York,” Cohn responded. About an hour later, Remple showed up happy which made Cohn happy. It was only later that Cohn realized why the Soviets were so excited to see them. “The Germans were afraid to be taken prisoner by the Russians, so they fought for every inch,” he explained. “The Russians realized when they saw us that there were no more Germans in front of them and that they had survived the war.”

A few days later, Cohn was back in Magdeburg when someone walked by his villa and said, “We got VE Day.” It was an anticlimactic end to the war. Two days later, Cohn’s team reported back to Wiesbaden where the unit broke up. Everyone was sent to different locations. Cohn spent the next year shipping German war criminal prosecution documents to the United States and guarding prisoners facing the Nuremberg trials for concentration camp officials.

Finally, in May of 1946, the T-Force’s chief of documents ordered Cohn to escort a stack of top-secret documents to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Cohn crossed the Atlantic onboard a Liberty ship where he took his meals at the petty officers’ mess. “Those were the best meals I had in the war,” he recalled. “I had to wait that long to get a decent meal.” He found the Navy meals much better than the tooth-chipping chocolate D-Bars he ate in the Army.

Once back home, Cohn returned to the City College of New York to finish his degree. There he reunited with Paula Brimberg, his Pong. Although he had never written to her during the war, they resumed dating, and in 1948 Cohn gave her an engagement ring, which she wore on a necklace under her clothes, so as not to shock her parents. Due to the post-war housing shortage, the couple still lived at their parents’ homes. Cohn tried to have a judge marry them, but the judge was only a magistrate. Undeterred, Cohn and Brimberg took a train to Brooklyn where a rabbi married them. They then both then went to their respective homes.

Eventually, they found an apartment, told their parents they were married, and moved out. They spent their honeymoon in Germany at Floh’s farm. Paula worked as a model until Cohn finished school in 1949. After graduating, he was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army. He spent 35 years in uniform as a Military Policeman, retiring as a Colonel. In 1964, Paula gave birth to a daughter, Laura. After his retirement, Cohn worked at the University of Maryland as an administrator and manager.

Over the years, Cohn has attended the annual Spirit of the Elbe observance at Arlington National Cemetery, until the Russian invasion of Ukraine suspended the event. He attended three WWII events in Moscow in 2005, 2010, and 2015. Today, he lives in Fort Belvoir, Va., where he serves on the Speaker’s Bureau of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. He also attends WWII events wearing his veteran’s baseball cap.

Looking back at the war, Cohn has few regrets. “I might have screamed bloody murder earlier that I could have gotten into the Richie Boys,” he jokes, but he admits that he would not have done anything radically different. His memories of the war remain sharp, and he is reminded of it almost every day. “To this day when I take a shower,” he says with a smile, “I always think of Liege.”

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel works as a historian for the U.S. Army. He is the author of Patton’s War, Volumes 1 and 2 and leads tours of General George S. Patton’s battlefields for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. His article “Fighting a Two Front War” for this magazine is being made into the major motion picture Six Triple Eight by Tyler Perry for Netflix.

The article states that IG Farben supplied Zyklon B to concentration camps. In fact, cyanide was notable by its absence from the companies production. They had a non-managerial shareholding in a separate company, Dagesh, which owned the rights to Zyklon B but neither produced nor distributed Zyklon B. A third company, Deassu Sugar Refining produced it, whilst two others distributed it. IG Farben was guilty of many crimes, but had no direct involvement with Zyklon B, which was in any case mostly (ca. 95%) used for legitimate pest control in concentration camps. At least one member of one of the distribution companies was aware of it being used for murders, but was still quite happy to supply it.