By Gabrielle Esposito

The Macedonian soldiers stood transfixed on the flood plain as the Pauravan army advanced toward them. The ground shook with each step the great lumbering war elephants took as they advanced toward the wide-eyed Greeks. In towers atop the elephants’ backs, expert archers fired down on the Greek spearmen.

Never before had the Greeks encountered elephants in battle. Although their commander, 30-year-old King Alexander of Macedon, had devised special tactics to deal with the elephants based on discussions with local allies, the average soldier had scant knowledge of the precautions their king had taken.

Soon the monstrous beasts, some of which let out an otherworldly scream as they waded into the Greek lines, were grabbing Greek soldiers with their great trunks and hurling them through the air. The Greek foot soldiers recoiled with shock and backpedaled toward the ferry landing on the Hydaspes River. Their officers shouted for them to hold their ground to no avail. Alexander had never been beaten in combat in a decade of conquest, but on this spring day in 326 BC he seemed closer to defeat than ever.

For the first time in the history of the Indian subcontinent, a large invading army had come from the west. Before Alexander’s arrival, India had only received small Persian expeditions. During the days leading up to the battle, the Macedonian infantrymen had learned of some strange, monster-like creatures that the Pauravan army employed in battle. The renowned Macedonian phalanx already had defeated many enemies. The Macedonians had shattered masses of Persian infantry, Greek mercenary hoplites, Scythian heavy cavalry, and the forces of many different Asiatic tribes, but elephants were something that went beyond their wildest comprehension.

The same feelings of fear and terror also were present within the army of King Porus of Paurava. He and his soldiers had heard many stories about the conquests of a young Macedonian king who led his men in battle as a god and who had never been defeated before in a pitched battle. Alexander had marched across the wide breadth of Asia, from the mountains of Anatolia to the steppes of Central Asia. He had fought in dozens of battles and skirmishes and been wounded many times, but he had always won.

The great conqueror had decided to continue his eastern march by heading across the plains of Punjab in search of more glory. A decisive battle for the history of India was going to be fought. It would be a battle that would shock Alexander, his army, and the entire Macedonian Empire.

In the months that followed the Battle of Gaugamela fought on October 1, 331 BC, King Darius III found temporary refuge in the satrapies of Bactria and Sogdia, which were ruled by the pow- erful governor Bessus. The latter had commanded the left wing of the Persian forces at the Battle of Gaugamela, comprising for the most part skilled warriors from his satrapies. Bessus had been able to survive, together with some part of his forces. He had fled to Ecbatana with Darius and then followed him when the great king decided to move east. Darius intended to raise a new army in the satrapies of Central Asia and undertake an offensive against Alexander.

In an effort to bring the war to an end, Alexander pursued Darius the following year. Bessus decided to organize a conspiracy against King Darius, with the other satraps of the Central Asian provinces. The traitors put Darius in golden chains, hoping that by giving their king to Alexander they could obtain some political advantage. Bessus was the most ambitious of the satraps. He hoped to replace Darius as the new Persian monarch and rule the vast eastern provinces of the Persian Empire.

The rebel satraps tried to surrender the deposed king to the Macedonians, but Alexander was not inclined to negotiate with them. He ordered his troops to continue their pursuit of the remaining Persian forces. But Bessus and the other satraps stabbed Darius and left him dying in a cart. Bessus immediately proclaimed himself king of Persia, adopting the name of Artaxerxes V. In many ways, his self-proclaimed ascension was logical since the Satrap of Bactria was traditionally the Persian noble next in the line of succession to the Persian throne.

The death of Darius had not led to an end of the war, which now continued between Alexander and Bessus. As a result, the Macedonians began their conquest of Central Asia, which would finally lead them to India. In 329 BC, the Macedonian army entered Bactria by way of the Hindu Kush mountain range, which had been left undefended by Bessus. Bessus wanted to move his forces farther east to weaken the morale of the Macedonians and make their supply routes too long. Having a superior knowledge of the terrain, he probably intended to conduct a guerrilla campaign against Alexander and his forces. This would entail a scorched earth strategy designed to weaken the Greeks through attrition.

After crossing the River Oxus, which marks the modern border between Afghanistan and Tajikistan, the Bactrian mounted troops deserted and abandoned Bessus, who was seized by several of his chieftains and handed over to the pursuing Macedonians. The last of the Persian kings was tortured and then executed in punishment for dethroning the legitimate monarch Darius.

Alexander had conquered nearly all of the territories of the Persian Empire, but some of the border regions had not yet accepted him as ruler and continued to resist. Oxyartes, one of the satraps who had betrayed Bessus, became the new leader of the Persian resistance forces. Alexander continued his advance north, capturing Samarkand and reaching the River Jaxartes, where he founded the city of Alexandria Eschate (Alexandria-the-Farthest).

Despite these successes, the Macedonians had to face a number of uprisings from the indigenous Sogdian and Scythian tribesmen, who remained loyal to Oxyartes. These mounted warriors of Central Asia used guerrilla tactics against the Macedonians, relying on their mastery of horsemanship and archery to attack the invading forces from a distance. During these small clashes Alexander lost more soldiers than in any other of his battles or campaigns. His soldiers grew weary of the skirmishing and did not see the point of campaigning in such an insignificant and poor region of the Persian Empire.

Alexander soon had a full-scale mutiny on his hands, which forced him to address his army’s internal problems. The Macedonian military leaders had never faced this sort of warfare before and thus had to develop new military tactics to defeat their nomadic enemies. They resolved to use catapults and archers in battle and to capture enemy strongpoints by siege even though they knew that this would be a time-consuming process.

Despite being injured on more than one occasion and suffering from dysentery, Alexander was ultimately able to win a decisive battle against the Scythians on the River Jaxartes. With the decisive defeat of the northern tribes, the Sogdians in the south decided to concentrate all their forces at a fortress called the Sogdian Rock. The stronghold, situated atop a large escarpment, was considered unconquerable by the peoples of Central Asia. The actual site of the Sogdian Rock is still debated to this day, but most archaeologists believe it was located near Samarkand. The Sogdians had a strong defensive position. After arriving at the site, Alexander grasped that the only way to assault the enemy position was to use a picked force of elite soldiers with mountaineering skills. They would scale the mountaintop fortresses with ropes and attack the defenders by surprise. The Macedonian leader called for volunteers, explaining to his soldiers the difficulty of this special mission, and 300 men volunteered.

Oxyartes of Bactria had previously sent his wife and daughters to take refuge in the fortress. He considered the Sogdian Rock the safest place for his family, but now the Macedonian soldiers were going to storm that position, too. The fortress did not have a large garrison, but it was well provisioned for a long siege. Alexander had asked the defenders to surrender before the attack, but they refused. They said that he would need “men with wings” to capture their stronghold.

Fortunately, Alexander could count on the volunteers who had offered to climb over the escarpment in exchange for the reward promised by their king. These men had gained a lot of experience in rock climbing from the previous sieges of the Central Asian campaign and were quite confident in the positive outcome of the delicate mission. Using tent pegs and strong flaxen lines, the 300 soldiers climbed the cliff face at night. They lost about 30 men during the difficult ascent. In accordance with their king’s orders, they signalled their success to the troops below by waving pieces of cloth. Elated at their success, Alexander sent a herald to shout the news to the enemy’s outposts to compel their surrender. The defenders, who were demoralized by the incredible achievement of the Macedonian climbers, decided to capitulate.

Alexander showed great magnanimity toward the captured Sogdians. He had no desire for revenge. He sought a durable peace in Central Asia so that he might embark on even more ambitious plans of conquest. To cement his ties with the tribal peoples of Central Asia, Alexander married Roxana, the daughter of Oxyartes. The decisive victory marked the end of Alexander’s Central Asia campaign and his conquest of the Persian Empire.

At that point, Alexander intended to invade India. But his soldiers were exhausted from the extended campaigns and the numerous hardships they had endured. Believing their sacrifices had finally come to an end, they longed to return to their homes in Macedon. Alexander, excited at the prospect of conquering an exotic land such as India, had no intention of stopping. He showed little consideration toward the feelings of his loyal veterans. Despite his soldiers’ wishes, Alexander led them east toward India in 326 BC.

Alexander was now the absolute ruler of Asia and presented himself as the direct heir of Darius. As such, he asserted his rights over the territories of northern India on the upper reaches of the Indus River, which had previously been part of the Persian Empire as the Satrapy of Gandhara.

These territories had been conquered during the rule of the early Achaemenid monarchs who followed Cyrus the Great. As a result, Indian military units, most of which were archers, had participated in the Persian campaigns against Greece. But Persian control over the Indian Satrapy of Gandhara had diminished by the time of Alexander’s arrival, and India was free from foreign rule. Searching for a pretext to expand into the Indian subcontinent, Alexander decided to impose again the rule of the Persian Empire over northern India. He invited all the chieftains of the former Gandhara satrapy to submit to his authority. One of these, the ruler of Taxila named Ambhi, readily accepted Alexander’s request. The Kingdom of Taxila soon became an important ally for the Macedonians. Taxila was an important ally both because of its location adjacent to India and because it had a large population that could furnish a substantial number of allied troops. But the other leaders refused Alexander’s request and prepared to fight against the invaders coming from the north. The most important of the Indian rulers who opposed Alexander was Porus, the ruler of the powerful Kingdom of Pauravas.

The kingdoms of Ambhi and Porus were divided by a long regional rivalry despite having the same ethnic origins. As a result, Alexander’s alliance with Taxila soon led to open war with the bordering Kingdom of Pauravas. Before descending to the plains of the Punjab region, though, Alexander had to fight some costly campaigns against the fierce warrior tribes of northern India. Alexander moved quickly to secure his northern flank from potential raids that might be launched by the Indian tribes of the Pamir and Himalaya mountain ranges. These tribes were the Aspasioi of the Kunar Valley, the Guraeans of the Panjkora Valley, and the Assakenoi of the Swat and Buner Valleys. All these tribes were fierce and warlike. Alexander’s campaign against them is known as the Cophen Campaign, which takes its name from the river that the Macedonians followed during their advance. The Macedonians marched swiftly along the Cophen River. As they marched to the Indus, they subjugated each village and city through which they passed.

Once the Macedonian army arrived at the Indus, Alexander ordered his troops to build a bridge as quickly as possible. The Aspasioi attacked the Macedonians, but the Macedonians prevailed and burned their opponents’ capital to the ground. The Guraeans adopted a different strategy. They assembled a large military force for a pitched battle. Despite their superiority in numbers, Alexander defeated them as well at Arigaeum.

Alexander’s next opponent was the Assakenoi. The Macedonians marched on their capital at Massaga. The Assakenoi boosted their army with the addition of 7,000 elite mercenaries from the Indian territories east of the Indus River. Because of their preparations, the Assakenoi were confident that they could defeat the invaders.

As soon as Alexander reached the outskirts of their capital, he launched a surprise attack. Alexander ordered his men to fall back to a hill one mile from Massaga. During their pursuit of the Macedonians, the Assakenoi became disordered. The Macedonians, who had retained a perfect order during their withdrawal, redeployed on the high ground. Alexander ordered his archers, light infantry, and light cavalry to counterattack. The Macedonians repulsed the Assakenoi attack then switched to the offensive. Alexander’s light troops advanced followed by the phalanx under the direction of Alexander, who was wounded while leading his troops.

The remaining Assakenoi warriors and mercenaries were obliged to retreat inside Massaga. Alexander then besieged the city. Although the Macedonians were proficient in siege operations, they encountered various difficulties on this occasion. The mercenaries put up a fierce resistance, repulsing various Macedonian attacks and launching raids outside the walls. Alexander’s forces had to build a siege tower with a long bridge and a terrace to attack the walls, but the siege machines were not enough to win the battle. Alexander even employed some of the same veterans who had stormed Tyre. The mercenaries ultimately surrendered when their commander was killed by a Macedonian arrow.

Afterward, Alexander continued to press his offensive against the tribes of northern India. Other fortified positions had to be assaulted and conquered by his forces, including the difficult siege operations against Aornos. By the spring of 326 BC, Alexander had secured his northeastern flank from any possible menace, and his forces were in full control of the Indian valleys located south of the Pamir and Himalayas. At that point, the Macedonians were ready to advance into the Punjab.

At the time of Alexander the Great and Porus, Indian armies included four different categories of troops: infantry, cavalry, chariots, and elephants. The infantry element was the most numerous, while chariots and elephants were the most prestigious. The Sanskrit epic poem Mahabharata equates the proportions of one elephant to one chariot, three cavalrymen, and five infantrymen. The army raised by Porus and deployed against Alexander included 200 elephants, 420 six-man chariots, 6,000 cavalrymen, and 30,000 infantrymen, according to the Greek historian Arrian. This was an impressive army for ancient times.

From a tactical standpoint, the Indian infantry and cavalry had no active or significant roles on the battlefield. Their main function was to protect the elephants and chariots by performing auxiliary duties. Each elephant or chariot received a certain number of infantrymen and cavalrymen. Pauravan armies often included contingents of mercenary archers and light infantrymen. The main difference between the tribal armies of northern India and those of the bigger states located in the plains was in the number of elephants and chariots. Due to the geographical nature of their territories, the northern Indian tribes had no chariots and few elephants. With the exception of nobles mounted on elephants or chariots, all of the Pauravan warriors deliberately chose not to wear armor.

All the components of the Pauravan army were lightly armed. The cavalry was entirely composed of light mounted javelin troops, while the infantry included front-rank spear- men, javelin troops, and archers. The soldiers in the front ranks were armed with spears and tall body shields but had no helmets or cuirasses. The javelin troops on foot were equipped with smaller shields and javelins and formed the largest part of the infantry.

The archers constituted the elite arm of the Pauravan infantry. Their superiority was due to the excellence of their main weapon. They were armed with heavy and powerful bamboo bows. Their arrows were 4 1/2 feet long and were made of cane or reed and flighted with vulture feathers. The arrowheads usually were made of iron, but sometimes they were made of horn. The use of poisoned arrows apparently was forbidden during the wars between Indian states, but in all likelihood they were employed against the foreign invaders led by Alexander.

Kings and nobles, fighting on elephants or chariots, were armed with javelins or spears and protected by brass helmets and scale armor. For secondary weapons the Pauravan warriors of Alexander’s time used swords, maces, and clubs. The former had a broad blade that was three cubits long and was used for powerful two-handed cutting blows, brought down from above the head. Clubs could be used in one hand, two hands, or thrown. Pauravan fighters were proficient with these primitive but highly effective weapons.

Alexander’s main army entered northern India via the Khyber Pass. After combining with the allied army of Taxila, the Macedonian forces advanced against King Porus and his kingdom. Porus was the head of one of the most significant regional powers of northern India. He was strong, tall, and courageous. As soon as Alexander formed an alliance with Taxila, Porus had begun assembling an impressive army to face the Macedonians in a large pitched battle. Unlike the northern tribes that had just been conquered by Alexander, Porus could not use the mountains or a complex of fortified cities to slow down the advance of the invaders, for his kingdom was located on the plains of Punjab. His only real advantage lay in assembling an army that would dwarf the one fielded by Alexander.

Porus deployed his troops along the east bank of the Hydaspes River, which marked the border between his realm and that of Taxila to oppose Alexander’s passage. He expected Alexander to wait for monsoon season to end before attempting to cross the river. Porus relied heavily on the Hydaspes, which at that time of year was swollen by monsoon rains and the melting snows of the Himalayas, to delay the Macedonian advance. The mighty Hydaspes was over a mile wide, deep, and swift. Porus’s plans would been perfect in an Indian war, but he was facing a different opponent. Alexander had great engineering skills, and he had surmounted all manner of challenges up to that point. Porus did not have an accurate measure of the enemy he was facing.

Alexander’s army encamped opposite Porus’s main defensive position on the east bank of the Hydaspes. Alexander successfully deceived Porus into believing that he fully intended to wait for the monsoon season to end. As a ploy, Alexander ordered large shipments of food and supplies from his allies in Taxila. In reality, the Macedonian commander had no intention of waiting.

Alexander’s army was smaller and more nimble than that of his Indian opponent. Alexander’s army consisted of veteran Macedonians augmented by contingents of troops from various warrior peoples that he had subjugated in Asia. Alexander’s army was less Macedonian than ever before. He had gradually transformed his army into a multinational force that retained its core of elite Macedonian phalanx and heavy cavalry.

The new Asiatic troops raised by Alexander would play a fundamental role in the upcom- ing battle. Alexander’s Asian auxiliaries were trained and equipped in the usual fashion of the Macedonian phalanx. This caused some anger among the Macedonian veterans, but it enabled Alexander to replace his losses and expand his infantry. Alexander allowed the Asiatic cavalry to fight in its traditional role as light cavalry. He knew well that the Asiatic light cavalry, which relied on javelins and the bow and arrow, would be useful in harassing the war elephants of Porus’s Indian army.

Porus enjoyed the advantages most armies enjoy when defending their own territory. For example, he had a short supply line and could hold his defensive position indefinitely. He intended to carefully guard the best possible river crossings and eliminate each wave of Alexander’s army as it came ashore.

To deceive his opponent, Alexander built numerous campfires along his side of the river, marching his men back and forth in formation; meanwhile, his scouts searched for the best possible crossing spot. “Alexander’s answer was by continual movement of his own troops to keep Porus guessing: he split his force into a number of detachments, moving some of them under his own command hither and thither all over the place, destroying enemy possessions and looking for places where the river might be crossed,” wrote Arrian. Porus’s forces stationed on the west bank of the Hydaspes initially shadowed each movement of the enemy on the opposite bank, but after a while they stopped. Porus eventually came to believe that all of the marching was nothing more than a diversion designed to confuse him.

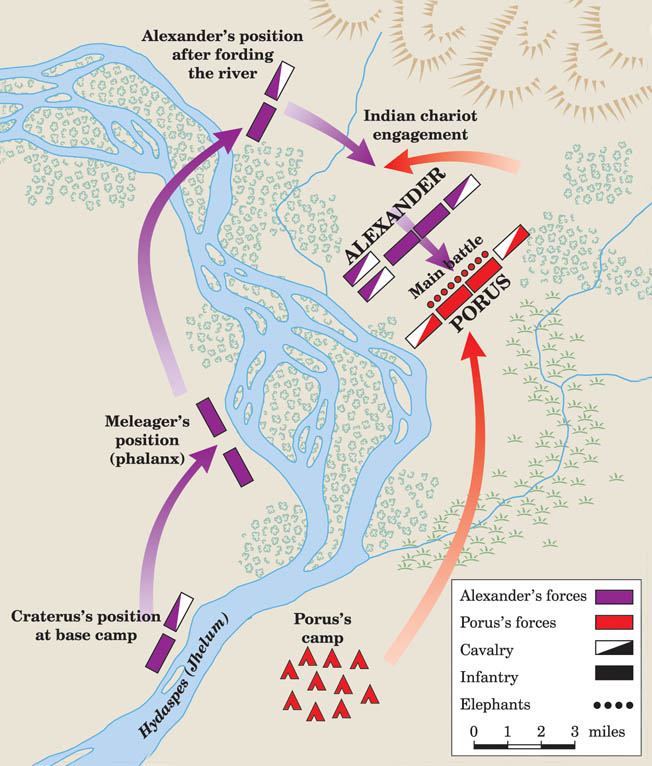

After a long and tedious search, Alexander’s scouts found a suitable crossing 18 miles upstream from the Macedonian camp at a heavily wooded bend in the river. Alexander believed it would offer good cover for his troops. To keep Porus unaware of his crossing, Alexander left General Craterus in the camp opposite Porus’s position. Alexander instructed Craterus to wait until the battle was underway to lead his reserve troops across the river.

The Macedonians arrived at the intended crossing during a heavy thunderstorm. The river could not be forded because of its depth, so Alexander ordered his men to construct rafts made from their tents. Alexander also ordered his engineers to haul as many as 30 boats used by his army to cross the Indus to the Hydaspes crossing. Alexander’s main force was composed of heavy cavalry, mounted archers, and various infantry units. Arrian says he had 6,000 foot soldiers and 5,000 horsemen. The troops cast off from the east bank under cover of darkness. The crossing did not go smoothly. Instead of reaching the opposite shore, the Macedonian soldiers landed on a large island located in the middle of the river. From the island to the opposite bank, the Macedonian soldiers had to swim since the channel between the island and the opposite shore was too narrow for the boats and rafts.

After reaching the opposite shore at dawn, Alexander regrouped his forces and put them in battle order. Some of his infantry units had not yet arrived, but Alexander advanced all the same. A defensive screen of Asiatic mounted archers, which included the famous Scythian archers, was placed in front of the advancing army to protect it.

Taken by surprise by the invaders, Porus tried to gain some time to deploy his troops. He sent a picked force of 3,000 cavalrymen and 120 chariots against the Macedonians led by his son. The Indian vanguard fought with great courage, but it was no match for Alexander’s heavy cavalry. Porus’s son was slain in the initial clash.

Next, Alexander led his army toward the Indian camp. After six miles, he halted to wait for the rest of his infantry to arrive. Alexander had no intention of making the fresh enemy troops a present of his own breathless and exhausted men, so he paused before launching the main attack.

Meanwhile, Porus deployed his main force for battle. He had approximately 20,000 cavalry, 4,000 light cavalry, and 200 war elephants. Porus did not mass his elephants together but instead placed them at regular intervals. His light cavalry was stationed on both flanks behind a screen of six-man chariots. The Pauravan infantry phalanxes, which were not as well trained or strong as the Macedonian phalanx, were placed not only behind the elephants but also between them. Porus took his position in the center of the line mounted on his elephant.

Alexander deployed his infantry phalanxes in the center with a protective screen of mounted archers and light cavalrymen in front of them. He took up his usual position on the extreme right with the Companions, the elite cavalry of his army. On the opposite flank, Coenus prepared to lead additional cavalry against the Pauravan right flank.

The battle began with the advance of Alexander’s light cavalry, which pelted the enemy elephants with a furious rain of javelins and arrows. At the same time, Alexander led the bulk of his cavalry against the Pauravan left flank. Coenus’s attack against Porus’s right wing caused no particular difficulties to the Indians, who were able to contain the Macedonian cavalry.

It was a completely different story on the Indians’ right, though. Alexander led his heavy cavalry in a spirited charge that drove back his adversaries. The effect of the Macedonian cavalry attack precipitated a crisis for Porus’s left wing. To face the emergency, Porus sent part of his cavalry from the right to circle back and help the left wing against Alexander.

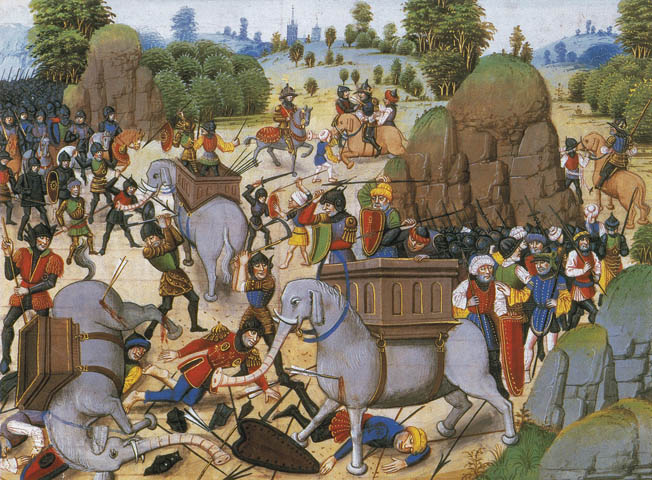

Shortly afterward, Porus ordered a general advance of his elephants against the Macedonian phalanxes. The elephants, which were organized into a separate corps, were used as shock troops. They were frequently used during the period against enemy cavalry because horses had a terrible fear of the animals and recoiled at their strong smell. But Porus’s elephants were not facing cavalry but rather a compact mass of heavy infantry. The psychological effect of the encounter on the Macedonian pikemen was unknown because it was the first time they had encountered elephants in battle. Likewise, Porus had no idea how his elephants would stand up to disciplined infantry.

The elephants charged into the Macedonian ranks, trampling the soldiers in their path. The Macedonians seemed on the point of breaking after the initial charge of the elephants. But the veteran infantrymen, who had faced all manner of enemies in their long trek from Macedon to India, began almost immediately to reorganize themselves. They gradually pulled back without breaking their ranks. Meanwhile, Alexander’s Asiatic horsemen harried the elephants from the flank, closely cooperating with the specially trained light infantry that stabbed the ele- phants’ legs.

Over time, the wounds Alexander’s tenacious foot soldiers inflicted on the elephants caused them to turn around and head for the rear. But the Macedonian cavalry had by then swung behind Porus’s army. The momentum then turned in Alexander’s favor. The Macedonian phalanxes had switched to the attack. Porus’s poorly disciplined infantry could not stand up to their Macedonian counterparts.

Porus’s elephants tired quickly, and their charges against the Macedonian infantry grew feeble as time passed. The elephants, maddened by the harassing attacks against their flanks and legs, then began to rampage through the dense ranks of Indian infantry as they sought to escape. This caused more damage to the Indian infantry than was inflicted by the enemy. It was not long before great gaps had been opened in the Indian infantry to be exploited by the Macedonians. Alexander’s phalanxes smashed into the lightly equipped Indian infantrymen, who were no match for them. Porus’s army by then was in complete disarray.

Coenus moved quickly to exploit the situation. He led a contingent of cavalry against the horsemen on the extreme right of Porus’s army. After driving them off, he also swept into the Indian rear to complete the envelopment of Porus’s hapless army. Porus’s left flank, which already had been routed by Alexander’s charge, was struck from behind both by Alexander’s horse and those led by Coenus. The only escape route left for Porus’s troops was to try to cross the Hydaspes. But Craterus brought Alexander’s reserve across the river, arriving on the battlefield at a crucial moment and adding their additional weight to the Macedonians’ final attack. Porus remained on his elephant throughout the battle and witnessed the complete destruction of his army. He had fought hard and as a testament to his valor had suffered severe wounds. The proud king could not accept defeat, though, and he encouraged his men to fight on.

Alexander, full of admiration for Porus, approached the defeated king with the intention of saving his life. As the carnage wound down, Alexander asked Porus how he wanted to be treated. The Indian leader responded that he wanted to be treated as a king. Alexander respected this request and told Porus that he would be able to remain king but must pledge his allegiance to Alexander. With little choice, Porus agreed to the terms. Following the battle, Porus became one of Alexander’s satraps. Alexander enlarged his kingdom by adding many of the territories he had conquered during the Cophen Campaign.

Alexander’s veterans and his allied soldiers had crushed Porus’s army. The Indian losses amounted to 12,000 killed, wounded, and missing, and 9,000 captured. In contrast, Alexander’s losses amounted to 1,000 men. One of the Macedonian casualties was Bucephalous, Alexander’s beloved horse, which died from wounds he suffered during the height of battle. It was a bittersweet moment for the great Macedonian king. As a special tribute to his beloved horse which had served him faithfully since his first adventures, Alexander founded the city of Alexandria Bucephalous on the west bank of the Hydaspes.

Alexander’s great triumph on the Hydaspes would be his last battle. His soldiers were too exhausted to continue the conquest of India. What is more, they were not inclined to face other Indian armies with elephants. In addition to the human cost of continuing the advance, Alexan- der’s army also would have had to cross the Ganges River, which was much bigger and wider than the Hydaspes. Once across, it would face the main army of the Nanda Empire. This army had 3,000 elephants and far greater numbers of cavalry and infantry than Alexander possessed, even if his army was heavily supplemented with Asian allies.

The restless Macedonian soldiers, eager for news from home, compelled Alexander to march back to Babylon. The Macedonian king, having fought more battles than many of history’s greatest commanders, boarded a ship that bore him down the Indus to the Indian Ocean. His army marched south to join him and they began the long trek back to Babylon. Three years later, in 323 BC, Alexander died in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon. Despite being outnumbered most of the time and fighting a wide variety of adversaries with different types of troops and tactics, Alexander never lost a battle. As he did at Hydaspes, Alexander showed that he could adapt and outfight any army no matter how different it was from his own.

After this victory, Alexander’s troops had enough and in majority decision, decided it was time to go home.

TROOPS VOTED TO QUIT? NOT TODAY.