By William E. Welsh

German Luftwaffe pilot First Lieutenant Gordon Gollob moved in for the kill at midafternoon on December 18, 1939, with his Messerschmitt Bf 110 against a formation of seven British Vickers Wellington medium bombers heading home from their bomb run against German battle cruisers in Wilhelmshaven harbor. He engaged the bombers over the East Frisian Islands on the southern fringe of the North Sea.

The air crews of 24 British twin-engined, medium bombers had flown together in a diamond pattern on their way to their objective. The British airmen had orders to bomb the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, both known to be in the harbor. Gollob piloted one of 44 German fighter aircraft from several German air wings around the Helgoland Bight that had scrambled when radar detected the inbound enemy bombers. Gollob was attached to a heavy fighter air wing consisting of Bf 110s that was based at Jever airfield west of Wilhelmshaven.

The Wellingtons broke up into smaller formations as they struggled to make it back to Suffolk. Gollob approached one formation from astern, firing on the rear left Wellington in the formation and knocking it out of the sky. “After the attack, I climbed to port and saw the Wellington, pouring out smoke from its stern, curve off the left and disappear downwards,” Gollob said afterwards. “An aircraft on fire over the sea is bound to crash into it.” Of the 22 Wellingtons that reached Wilhelmshaven, 12 were shot down and three others were so badly damaged that they crash-landed in England. Afterwards, the British restricted their bombing raids to the nighttime.

By the end of World War II, Gollob would be one of the most decorated fighter aces in the annals of the Luftwaffe. He would be one of the select few that held Nazi Germany’s highest military decoration, the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds. Of the 10 million German soldiers, sailors, and airmen, only 862 received the illustrious Oak Leaves cluster to the Knight’s Cross, and just 27 obtained the Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds.

Gollob dreamed of being an aircraft pilot as a young boy. His innate talents as a mechanical engineer led him to build a glider at the age of 18 that he flew from a civilian airfield in Innsbruck. It was natural for him to enroll in a mechanical-engineering program at the University of Graz. Yet he only completed four semesters before joining the Austrian armed forces in 1933.

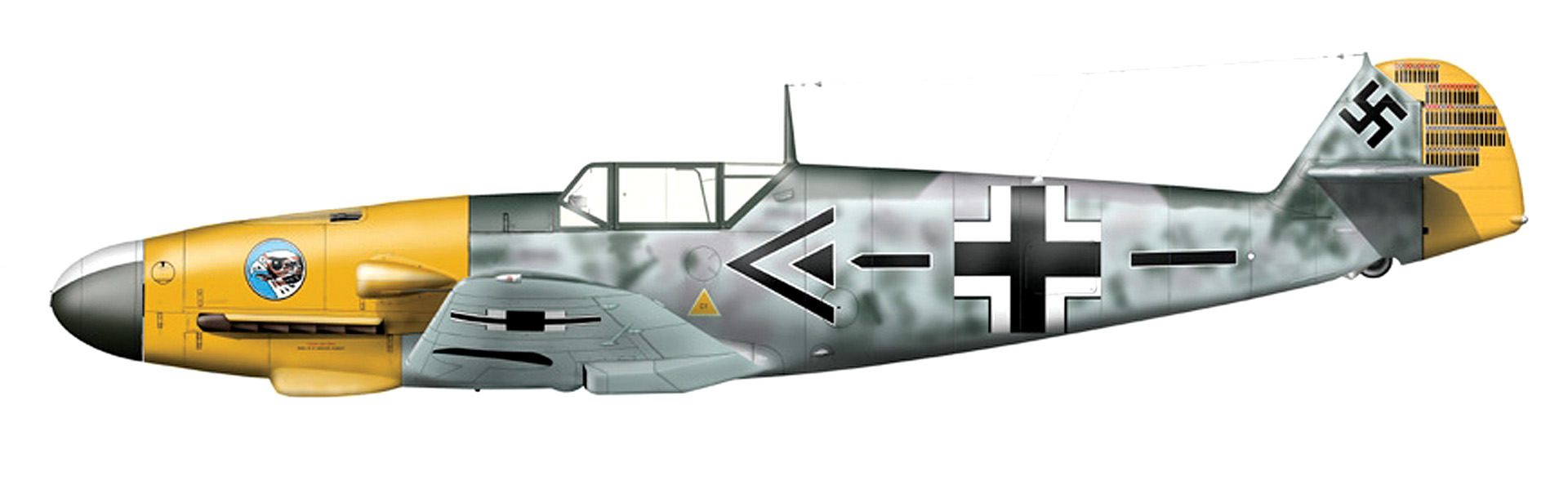

Three years later he received a promotion to second lieutenant and became an instructor in an Austrian flight-training squadron. When Nazi Germany absorbed Austria through the Anschluss in March 1938, Gollob transferred to the Luftwaffe, obtaining in just a few months the rank of first lieutenant with the third squadron of Zerstorergeschwader 76 (destroyer wing 76). He qualified to fly both the single-engine Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the twin-engined Messerschmitt Bf 110 heavy fighter. While the Bf 109 was a single-seater, Bf-110s were two-seaters crewed by a pilot and radio operator as well as a rear gunner.

Gollob’s first kill, a Polish biplane, came on the fifth day of the German invasion of Poland, which began on September 1, 1939. In the days that followed, he participated in ground-attack operations during which he succeeded in destroying a number of Polish aircraft on the ground. For these achievements, he received the Iron Cross 2nd Class on September 21.

Gollob was appointed squadron leader of the 3rd Squadron of ZG 76 on the day before the German invasion of Denmark and Norway. ZG 76 was part of Fliegerkorps X, which comprised four bomber wings and one fighter wing. During the invasion, which began on April 9, 1940, only two Bf 110 aircraft from Gollob’s squadron reached their objective, which was Stavanger-Sola airfield in Norway. Gollob piloted one of the two aircraft. The squadron’s remaining aircraft were either missing or had been forced to turn back because of the inclement weather.

Gollob had orders to use his aircraft to support the 100 Fallschirmjaeger (paratroopers) whose mission was to seize control of the airfield so that Ju-52 transports could land with additional troops and equipment. When the two aircraft arrived, the Fallschirmjaeger were pinned down by fire from two gun emplacements manned by determined Norwegians on the perimeter of the airfield. Gollob and the other aircraft flew low over the airfield with their cannon and machine guns roaring. The crucial ground support enabled the Fallschirmjaeger to mop up resistance.

Gollob’s squadron was eventually based at Trondheim in central Norway, where it patrolled the North Sea. Fifteen Blackburn Skua dive bombers took off from the British aircraft carrier Ark Royal on June 13 to attack the Scharnhorst, which was anchored in Trondheim Fjord. Gollob and other Bf 109 pilots scrambled to intercept the dive bombers. In the ensuing air battle, the German fighters downed eight of the British aircraft. Gollob, who scored the first kill in the air battle, received the Iron Cross 1st Class the following day.

The German Wehrmacht subsequently achieved a surprisingly rapid and thorough victory over France owing in large part to its superb blitzkrieg tactics. While the ground troops were mopping up in France in June 1940, Luftwaffe Reichsmarschall Herman Goering issued an operational directive for his aerial branch to redeploy its units to wage war on Great Britain’s Royal Air Force.

The weighty task before the Luftwaffe was to destroy the RAF in preparation for an amphibious invasion of southeastern England. Such an invasion was impractical, however, because the Kriegsmarine (German navy) had suffered devastating losses in the Norwegian campaign and lacked the assets necessary for ferrying troops across the English Channel. In addition, the Luftwaffe would be hard-pressed to achieve air superiority given the limited range of the Bf 109s. German Bf 109 pilots could only remain over southeastern England for about 20 minutes before having to turn back to their bases on the Continent.

As the Germans began their air campaign against the RAF using bases in France and the Low Countries in July 1940, Gollob remained stationed in Norway. During this time, he made recommendations for technical improvements of the Bf 109, which he had access to on the base where he was stationed, and subsequently traveled for a brief period to the Luftwaffe test facility in Pomerania to consult with the facility’s engineers.

After returning to Norway, he was patrolling the North Sea when he shot down a Short Sunderland patrol-bomber seaplane at midafternoon on July 9, 1940, about 90 miles southwest of the Shetland Islands. Continuing his patrol in a Bf 110 with two other crewmen, he then shot down a Lockheed Hudson coastal-reconnaissance aircraft two hours later.

Gollob did not receive orders transferring him to the new theater of war until September 7, 1940. His transfer coincided with the point when the Luftwaffe switched its strategy from attacking RAF facilities to bombing London. The first lieutenant joined the headquarters unit of the 3rd Fighter Wing, based at Arques in the Pas-de-Calais region.

When the commander of the 3rd Fighter Wing was shot down over England on October 8, Gollob was appointed to replace him. The airmen in the fighter wing were sent to Germany in February 1941 for a rest. The wing began redeploying in late April to Monchy-Breton in Pas-de-Calais, and upon their return to service they received new Bf 109F-2 aircraft. During his time on the Western Front, Gollob accrued additional six aerial victories.

Gollob subsequently downed a Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft on May 7 while engaging British aircraft operating along the French coastline. His superiors promoted him to captain on June 1. Gruppe II of Generaloberst Alexander Lohr’s Luftflotte 4 (4th Air Fleet), to which Gollob belonged, transferred that month to Breslau-Gandau in Poland in preparation for Operation Barbarossa. Luftflotte 4 had orders to support Army Group South in its capture of the Ukraine.

On the first day of Operation Barbarosa, June 22, 1941, Gollob shot down a Polikarpov I-16 fighter aircraft. In the months that followed, Gollob encountered and shot down a wide variety of Soviet fighters and bombers on the Eastern Front. These included Soviet-made fighters such as the Yakovlev Yak-1, Polikarpov I-153 biplane, and Lavochkin-Gorbunov-Gudkov LaGG-3, as well as bombers such as the Ilyushin DB-3 torpedo bomber, Petlyakov Pe-2 dive bomber, Tupolev SB-2 fast bomber, and Ilyushin Il-2 fighter bomber.

In addition to the ongoing battle for air supremacy, Gollob and other fighter crews carried out missions such as protecting armored spearheads, escorting Stuka dive bombers to target, and strafing Soviet airfields.

Gollob received his first so-called ace-in-a-day achievement on August 21, 1941, when he downed five aircraft in one day. It would be the first of half a dozen of these achievements that he would amass during his career as a fighter pilot. In August 1941 he received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for his steadily rising count of aerial victories.

In October, Gollob had three dozen victories, of which nine occurred as Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center pressed its attack on Moscow during Operation Typhoon. By month’s end he had a total of 85 aerial victories, for which he received Oak Leaves for his Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. Hitler summoned Gollob to his Wolf Lair’s headquarters at Rustenburg on the Eastern Front to personally present the decoration to him.

After a short stint supporting Army Group Center’s drive on Moscow, Luftflotte 4 returned to support Army Group South in mid-October as it pushed into the Crimean Peninsula. During the Crimean campaign, a fellow pilot in the 77th Fighter Wing reported on the kind of aerial tactics Gollob used: “Gollob flew from Kerch together with his wingman,” the pilot said. “They positioned themselves at a low altitude beneath a Soviet formation. Then they started climbing in spirals, carefully maintaining their position beneath the enemy formation. Before the peacefully flying Soviets had even suspected any mischief, the two planes at the bottom of their formation had been shot down and the two Germans were gone.”

By that point, the Luftwaffe high command had groomed Gollob for command of an air group. After undergoing additional training, he was appointed commander of Jagdgeschwader 77 (the 77th Fighter Wing) on May 16, 1942. That same month he achieved his 100th aerial victory, for which he received the Swords decoration for his Knight’s Cross. By late summer 1942, he had achieved an unprecedented 150 aerial victories, for which he received the exalted honor of Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds.

Because he was being groomed for a post in the high command of the Luftwaffe, German leader Adolf Hitler forbade Gollob from flying any further combat missions. In October 1942, he was appointed Jagdflieger Fuhrer 3 in northwestern France, where he oversaw fighters defending the Atlantic Wall. A year later he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of Jagd Division 5 (5th Fighter Division), also on the Western front. Two months before D-Day, though, he joined the staff of the Inspector of Fighters and eventually became Inspector of Fighters with the rank of Generalleutnant (major general).

Frustrated with the inferiority of German fighters to the increasingly sophisticated Allied fighters and ground-attack aircraft, Gollob openly clashed with Hitler over the best use of the jet-powered Messerschmitt Me 262 aircraft, introduced in April 1944. Although originally envisioned as an interceptor, Hitler wanted it used as a multipurpose fighter-bomber. Gollob vehemently disagreed with this use of the Me 262. Hitler had entrusted Gollob with the operational deployment of the sophisticated jet aircraft but was angered by what he perceived as Gollob’s uncooperative behavior. Despite Hitler’s ill will, Gollob returned to the battlefront in November 1944 when he was given command of the special fighter command on the eve of the Ardennes Offensive.

Gollob was taken into captivity in April 1945 in the Alpine Fortress by elements of the U.S. 36th Infantry Division. After extensive interrogation, he was released the following year. He survived the war and died in Lower Saxony in September 1987 with the distinction of having been the first Luftwaffe fighter ace to reach 150 aerial victories in World War II.