By Michael D. Hull

On March 3, 1945, the 27,100-ton aircraft carrier USS Franklin churned out of Pearl Harbor and headed westward for the war zone. She was accompanied by the battlecruiser USSGuam. At the great U.S. naval base of Ulithi, the Franklin’s Task Group 58.2 merged with three other forces to form Task Force 58. Its mission was to launch the first carrier strike against the Japanese Home Islands since the Doolittle raid of April 1942.

The armada steamed northward, stretching for 50 miles across the Pacific Ocean. On the night of March 17, the fleet closed to a mere hundred miles from the Japanese coast. An hour before dawn the following morning, the flattops launched their fighters and dive-bombers against airfields on Kyushu.

Americans Draw First Blood

The raids continued all day long, and the Franklin’s air group alone downed 18 enemy aircraft and destroyed many others on the ground. The Japanese reacted with characteristic fanaticism, and a dozen suicide planes were shot down almost within sight of the American task force.

The fateful day of March 19, 1945, dawned coolly as the Franklin swung into the wind to launch her first flight—a fighter group armed with special heavy rockets to attack enemy naval units at Kure.

At 6:55 am that St. Joseph’s Day, another flight swept off the deck, bound for a strike at Kobe. A thousand yards away, the carrier USS Hancock was sending up her first planes of the day. Ahead and astern of the Franklin were the light carriers Bataan and San Jacinto.

A Quiet Breakfast Rudely Interrupted

Thirty more Helldivers warmed up on the Franklin’s flight deck, while in the wardroom a few officers were eating breakfast. Among them was gentle, scholarly Lt. Cmdr. Joseph T. O’Callahan of Massachusetts, the ship’s Roman Catholic chaplain.

Suddenly, at 7:07 am, a Japanese Yokosuka D4Y Judy bomber flashed out of a cloudbank and hurtled down toward the Franklin at 360 miles an hour. The carrier’s 5-inch and 40mm guns opened up on the plane as it released two 500-pound armor-piercing bombs, pulled up, and turned away only 50 feet above the flight deck.

The first bomb slammed into the forward hangar deck, ripping a great hole in the three-inch armor plate and setting fire to fueled and armed planes. The second bomb smashed through two after-decks and exploded on the third deck near the petty officers’ quarters.

The Franklin Becomes an Inferno

The flattop reeled as a column of black smoke poured from the forward elevator well and a sheet of flame shot up from the forward starboard edge of the hangar deck. Smoke and flame engulfed the planes on the flight and hangar decks, and violent explosions began to convulse the carrier.

Ready-ammunition lockers filled with rockets and shells detonated, and smoke billowed into the engine rooms below. Scores of men perished on the flight, hangar, and gallery decks. The proud Franklin was an inferno.

Chaplain O’Callahan hastily left his unfinished breakfast and made his way through the shambles of smoke, flames, and torn steel to do what he could to comfort the wounded and steady the able-bodied. He seemed to be everywhere—helping, cajoling, inspiring. His quiet courage heartened all who came in contact with him, and the big white cross on his helmet became a beacon of hope for the dazed crew of the stricken ship.

“Look at the old man [Captain Leslie E. Gehres on the bridge] up there,” O’Callahan told the sailors. “Don’t let him down.”

A Life Dedicated to Serving God and Man

During his few days aboard the Franklin, Chaplain O’Callahan had made many friends among crewmen of all faiths. To the Protestant sailors, he was “Padre Joe.” To the Jews, he was “Rabbi Tim.”

Born in the Roxbury section of Boston on May 14, 1905, Joseph Timothy O’Callahan attended St. Mary’s Parochial School in Cambridge, and then went on to Boston College High School. He was a solid student in the college preparatory course. He wrote for the class magazine, acted in the dramatic society, and ran on the relay team.

Deciding on a career in the service of God and man, young Joseph entered the Society of Jesus at the St. Andrew-on-Hudson Novitiate in Poughkeepsie, NY, in July 1922. Two years later, he pronounced his first vows as a Jesuit. After completing philosophical studies at Weston College, he joined the Boston College physics department as a teaching member in 1929.

Then it was back to Weston College in 1931 to begin formal theology studies. He was ordained on June 20, 1934. After tertianship at St. Robert’s Hall in Pomfret Center, Conn., and a year of special studies at Georgetown University, O’Callahan was appointed to teach cosmology to his brother Jesuits at Weston College. In 1938, he was transferred to Holy Cross College in Worcester, Mass., to teach mathematics and physics.

By 1940, the priest-scholar who loved both mathematics and poetry was head of the math department and had founded a math library. His students admired their energetic, friendly, and sometimes fiery instructor.

His Country Called him to Service

But much of the world was by now at war, and Joseph O’Callahan grew restless. He applied for a commission as a Navy chaplain.

His colleagues tried to dissuade him. They felt his talents could serve the war effort best at Holy Cross, soon to have one of the leading Naval ROTC units in the country. But logical argument was no match for O’Callahan’s quiet determination, and on August 7, 1940, he was commissioned a lieutenant in the Navy Chaplain Corps.

His first assignment was teaching calculus at the Pensacola, Fla., Naval Air Station. But he yearned for sea duty, preferably aboard a carrier. After 18 months of shore duty, Chaplain O’Callahan went to sea. In April 1942 he reported aboard the carrier USS Ranger.

The Ranger made few headlines but saw plenty of action from the Arctic to the Equator. She played a leading part in the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, and in an October 1943 raid on German shipping in Norwegian waters.

Chief Morale Officer

With the rank of lieutenant commander, O’Callahan served as the Ranger’s chief morale officer. He made many friends, and at his funeral 20 years later officers and men from the carrier presented a crucifix in memory of their padre.

After two and a half years aboard the Ranger, O’Callahan was reassigned to shore duty—at naval air stations at Alameda, Calif., and Ford Island, Pearl Harbor. He was able to relax after the rigors of combat and spent his free evenings reading poetry.

But he also had time to worry. His youngest sister, Alice, now Sister Rose Marie, a Maryknoll nun, was imprisoned in a Japanese detention camp. For three years the family had not heard a word about her. Chaplain O’Callahan prayed that he would be assigned to the Philippines so that he could learn the fate of his sister.

Chaplain O’Callahan Sets Sail on Big Ben

The Navy had something else in store for him, however. He was ordered back to sea. At Pearl Harbor on the afternoon of March 2, 1945, amid piles of potatoes and ammunition, Chaplain O’Callahan reported for duty aboard the carrier USS Franklin (CV-13).

Known affectionately by her crew as the “Big Ben,” the Essex-class carrier was the fifth American warship to bear the name. The carrier’s keel had been laid at Newport News, Va., on July 12, 1942, and she had been completed on January 31, 1944. When O’Callahan went aboard her, she had already seen much action and had almost been sunk.

As part of Task Group 58.2 in the Pacific Theater, the Franklin had sent her planes against Japanese bases in the Bonin Islands, Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, Ha Ha Jima, Guam, Palau, Yap, Peleliu, and Luzon. She had had several close calls, saved only by the skilled seamanship of her commanding officer, Captain James M. Shoemaker, and her crew.

Japanese Navy Threatens and Seventh Fleet Responds

As the flagship of Task Group 38.4, the Big Ben was present with the mighty Seventh Fleet on October 21, 1944, when troops of the U.S. Sixth Army poured ashore at Leyte. Three Japanese fleets threatened the Americans at Leyte, and Task Group 38.4 wheeled westward to engage the enemy.

The Japanese super battleships Musashi and Yamato staggered beneath bombs from Franklin’s planes. Two enemy cruisers were hard hit, one was left dead in the water, and another blew up. Off the entrance to Leyte Gulf, fighters from the Franklin sank the large enemy carrier Zuiho.

Early on the afternoon of October 29, 1944, a small group of well-camouflaged Japanese suicide planes approached the Franklin’s force. Cruisers and destroyers closed in tightly around the Big Ben and the carriers Enterprise, Belleau Wood, and San Jacinto. Every 5-inch gun in the formation opened up.

Big Ben Takes Direct Hit but Limps Home

The enemy pilots pressed home their attacks. A suicide plane crashed into the after-end of the Franklin’s island, and a great explosion rocked the flattop. Flames and smoke smothered the hangar and flight decks. Two dozen men died in the blast, and many gunners were scorched by flames and blinded by fumes. Damage-control parties fought the fires, and 20 minutes later another great blast shook the Big Ben. She listed to starboard.

The ship had lost 57 men and suffered severe damage, but she stayed afloat and gained an even keel after hours of effort by her crew. She retired to Ulithi, where Captain Shoemaker was relieved by Captain Gehres. After brief repairs in Pearl Harbor, the flattop was ordered to the Bremerton, Wash., Navy Yard for an overhaul.

The repairs were completed in January 1945, and the Franklin took on a new air group at Alameda before steaming back to Pearl Harbor.

The Darkest Hour

Now, on the morning of March 19, 1945, the inferno aboard the Big Ben intensified as 40,000 gallons of aviation fuel on the aft hangar deck fed the fires. Hundred-foot-high flames shot up past the carrier’s island, and a column of smoke rose a mile above the clouds.

Heedless of danger, the destroyer USS Miller eased alongside the stricken flattop and trained her hoses on the fires. At 8:30 am, only the Franklin’s two after-fire rooms and the after-engine room were still operative, but the heat and smoke became unbearable and they had to be evacuated.

Dozens of sailors had been blown overboard by the force of the explosions, and others had jumped into the sea to escape the flames. Many sailors below decks were trapped, and they struggled to make their way topside. Everyone in the ship’s hospital ward—doctors, corpsmen, and patients—died after a futile struggle against fire and suffocation.

Courage Amid the Flames

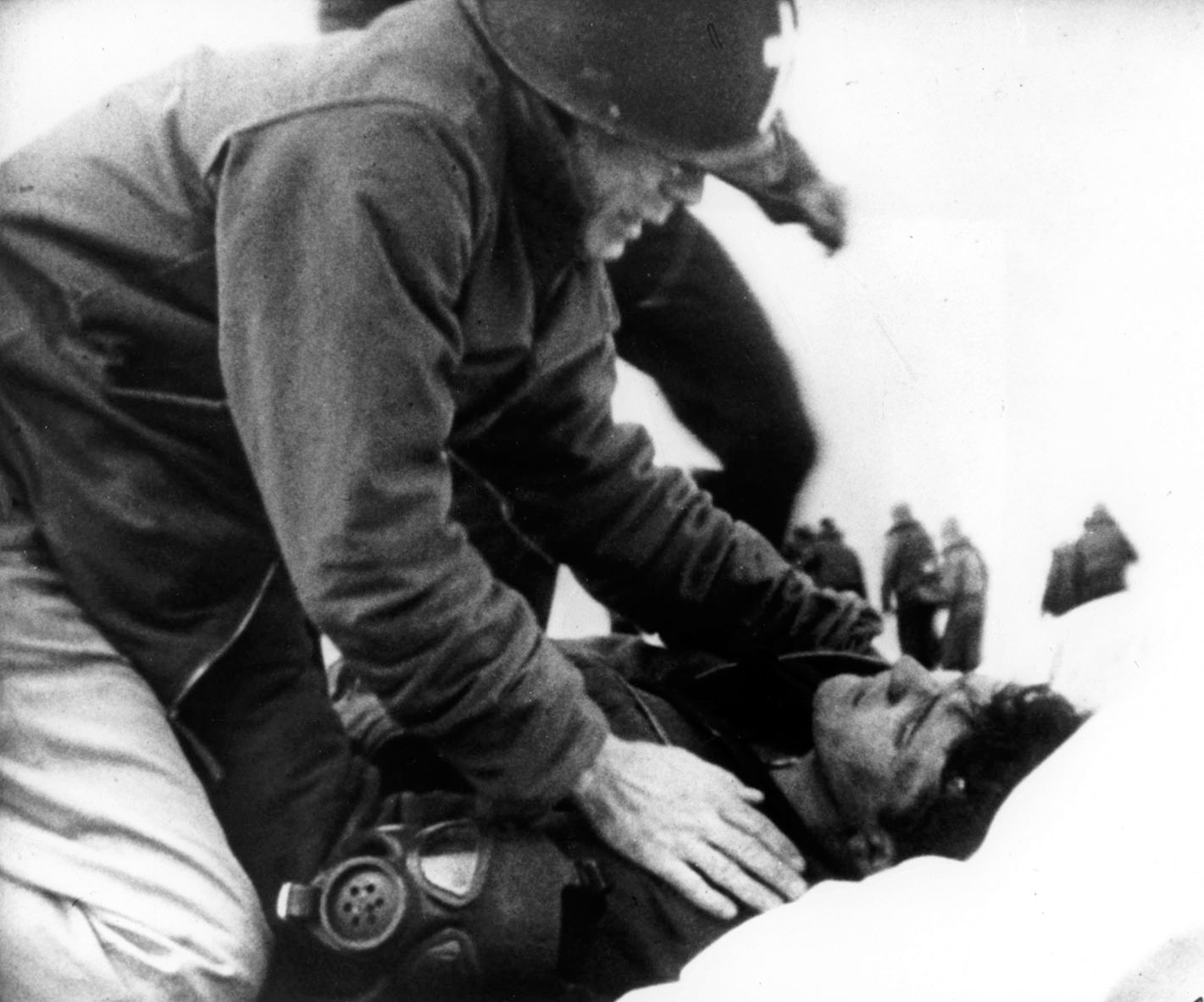

Although wounded himself by shrapnel, Chaplain O’Callahan dashed about the slanting flight deck, administering last rites to dying sailors and comforting the wounded. He led officers and men into the flames, carrying live bombs and shells to the edge of the deck for jettisoning. O’Callahan personally recruited a damage-control party and led it into one of the main ammunition magazines to wet it down and prevent it from exploding. Back on deck, he grabbed a hose to dampen live bombs that were rolling dangerously about.

Captain Gehres later called O’Callahan “the bravest man I ever saw.” The chaplain retorted, “Any priest in like circumstances should do, and would do, what I did.” He dismissed later publicity as “exaggerated.”

The cruiser USS Santa Fe moved alongside, all hoses pouring water on the Franklin’s burning decks. The carrier listed lower and lower. Steam ceased to flow from the boilers, and she lost steering control at 9:30 am. She lay dead in the water a mere 50 to 60 miles from Japan, the closest any American surface ship had approached so far during the war.

The Ship That Wouldn’t Die

The Santa Fe took off the carrier’s wounded, and destroyers circled around picking up survivors. After one abortive try, the cruiser USS Pittsburgh managed to connect her tow line with the crippled flattop and start hauling her southward at a speed of three and a half knots.

Firemen slowly worked their way back to the engineering spaces, and by 7 pm that St. Joseph’s Day most of the fires below decks were under control. For the second time, the USS Franklin had refused to sink despite severe damage. She would henceforth be known as “the ship that wouldn’t die.”

That night, the Japanese were out in force dropping flares on the horizon in their search for the Franklin, but their efforts to finish her off were foiled. Instead, they encountered American task groups, and a furious encounter raged through the night just 10 miles away from the limping flattop.

Japanese Determined to Finish off the Franklin

Shortly before dawn on March 20, the engineers labored over their engines trying to find a way to get up more steam. Still under tow, the ship was moving at a mere six knots and was still only 85 miles from Japan. Yankee ingenuity won out, and by 10 am the Big Ben was churning forward under her own power at 14 knots. Her escorts were the battlecruisersGuam and Alaska and a pair of destroyers. The little group steamed slowly southward, but the enemy had not given up in its determination to finish off the Franklin. That afternoon, Japanese planes bore down on the five ships.

The cruisers drew in close to shield the carrier, for another hit could send her to the bottom. One enemy plane swept in close to loose a bomb on the carrier, but her few remaining antiaircraft mounts opened fire with such speed and accuracy that the astonished Japanese pilot was forced to swerve away. His bomb fell harmlessly into the sea a hundred feet from the ship.

Repeatedly, the Japanese sent bombers in a desperate effort to reach the Franklin, but each time they were chased off by fighters from a task group 30 miles away.

“God Won’t Let Me Go Until He’s Ready!”

Meanwhile, Chaplain O’Callahan stayed at his post for three wearying days and nights. Strafing Japanese fighters failed to shake him. When his skipper yelled, “Why don’t you duck?” the chaplain shouted back with a grin, “God won’t let me go until He’s ready!”

The carrier continued to pick up speed, and by sunset on March 20, she was steaming at more than 20 knots. By dawn the following day, she was 300 miles from Japan. That evening, she rejoined Task Group 58.2, which was retiring to Ulithi.

On March 24, the Big Ben dismissed the screening destroyers Miller, Marshall, and Hunt to take her place in the column of ships steaming into Ulithi Lagoon. Two days later, accompanied by a pair of destroyer escorts, the Franklin and Santa Fe set course for Pearl Harbor. They arrived on April 3, 1945.

Solemnity and Humor Greet the Wounded Franklin

It was an emotional event when the battered, blackened carrier inched into Pearl Harbor. Hardened Navy veterans wept openly at the sight. But there was a touch of wry humor, too, as a nondescript band made up of tin pans, an accordion, and two horns, and organized by Father O’Callahan, played and sang, “Oh, the old Big Ben, she ain’t what she used to be.”

During a five-day stay at Pearl Harbor, the doughty chaplain set about organizing “a most exclusive club,” the 704 Club. This comprised the 704 survivors of the March 19 bombing who stayed aboard the Franklin and would sail her home.

On April 9, the carrier started her engines, lifted her anchors, and got underway eastward from Pearl Harbor. A week later, she inched through the Panama Canal, and on April 28, 1945, she arrived off Gravesend Bay, NY. Two days later, she eased into the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where she was to undergo extensive repairs.

Unsurpassed Survival and 388 Decorations For Franklin Crew

After a merciless battering by bombs, fires, and explosions, and an incredible 13,000-mile voyage that was a testament to the seamanship and fortitude of her crew, the old Big Ben was home. Her survival was unsurpassed in U.S. Navy annals. As Captain Gehres said simply, “A ship that will not be sunk, cannot be sunk.”

No less than 388 decorations were bestowed on the crew of the Franklin. It was the greatest number of medals ever awarded to the personnel of a single ship in American history.

Meanwhile, the crew went on rehabilitation leave as Navy Yard crews went to work on the hulk, toiling day and night to cut away entire sections of blasted deck. She was still undergoing repairs when the war ended.

Heroic Chaplain Receives Medal of Honor

Chaplain O’Callahan was assigned briefly to the Office of Public Information at the Navy Department, and then the Newport, RI, Naval Training Station. He returned to his alma mater, Georgetown University, as commencement speaker on June 17. He received an honorary doctor of science degree and told the graduates, “Take life seriously, which means for your happiness that you live your life as God would have you lead it.”

In October 1945, the chaplain reported for precommissioning duty aboard a brand-new carrier, the 45,000-ton USS Franklin D. Roosevelt. His proudest moment came on January 23, 1946, when he stood in the White House while President Harry S Truman placed the pale blue ribbon of the Medal of Honor around his neck for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity.” O’Callahan’s mother watched. He was the first Roman Catholic chaplain to be awarded the nation’s highest decoration for heroism. He also received the Purple Heart and five campaign ribbons.

In June 1946, O’Callahan was appointed escort chaplain to accompany the body of Filipino President Manuel Quezon to Manila aboard a U.S. Navy vessel. On November 12, 1946, he was released from service with the rank of captain.

Franklin Decommissioned and O’Callahan Returns to Academia

The Franklin, meanwhile, was decommissioned on February 17, 1947. She had earned four battle stars on the Asiatic Pacific service ribbon.

O’Callahan went back to Holy Cross to teach philosophy and locked his Medal of Honor in the Dinand Library safe. The war had taken a toll on him, and he would never again enjoy good health.

In December 1949, he suffered his first stroke. His right arm was paralyzed, but he exercised daily to restore the limb to usefulness. It was a tough fight, but each summer he would prepare meticulously for the fall classes, hoping that by September he would be strong enough to return to the classroom. He started writing what would be a best-selling memoir, I Was Chaplain on the Franklin, and a personal letter from President Truman spurred him on.

O’Callahan’s greatest source of strength was daily Mass. He received permission to offer his Mass sitting down, for on some days he had to literally drag himself to the altar. His health continued to fail, and on some days he was able to compose only a short paragraph for his book.

Father O’Callahan Remembered With Ship Dedication

Transferred to a room at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Worcester, Father O’Callahan took a turn for the worse on the afternoon of March 18, 1964. At 10:40 that night, while five Jesuit brother priests and two Sisters of Providence prayed, the chaplain of the Franklin died. Three days later in the little cemetery at Holy Cross, he was buried in a simple Jesuit ceremony. A Navy bugler sounded taps over the grave while the Navy chief of chaplains, three Catholic bishops, and O’Callahan’s 90-year-old mother listened.

Along with the ship that would not die, Chaplain O’Callahan was now part of U.S. Navy history.

In July 1968, Richard Cardinal Cushing of Boston officiated at the commissioning of a destroyer escort named for Father Joe at the Boston Navy Yard, saying he was “an inspiration for all future time.” The ship was christened by the chaplain’s youngest sister, Alice, then Sister Rose Marie. She was the first nun to christen a U.S. warship.

Chaplain’s Courage Serves as Inspiration and Guidance to Future Sailors

Father Joe also was memorialized at the Chaplains Memorial in Valley Forge, Pa.; his helmet, rosary, and miraculous medal are on display in the USS Franklin CV-13 Museum aboard the carrier USS Yorktown in Charleston, SC; and a stained-glass window honors him in the sacristy of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, DC.

The epic of the USS Franklin inspired both the Navy and the public. The Navy used the story to produce a training film to teach recruits about duty, firefighting, and survival, and a color documentary, Saga of the Franklin, was made.

Hollywood Swings and Misses on Telling his Story

In 1956, Columbia Pictures released Battle Stations, a semifictional account of the Franklin. John Lund starred as Chaplain McIntyre, loosely based on Chaplain O’Callahan, and the film costarred William Bendix, Richard Boone, and Keefe Brasselle. Lewis Seiler directed. The film received poor reviews. Critics said that it was riddled with stereotypical characters and that the script contained every service movie cliché imaginable.

An NBC-TV special documentary, The Ship That Wouldn’t Die, was telecast in April 1969. It featured interviews with several crewmen, and was narrated by Gene Kelly.

Another great untold story of a W II hero. The movie was definetely poorly scripted and acted. The military channel had a good documentary on the Big Ben. Your article does not note how many sailor died on Big Ben.

Are there any survivors of the 704 Club?

Captain Gehres took all the credit for the saving of the Franklin when I was later reported he was in panic on the bridge talking to a photo of his wife while others took over and issued orders. Crewman were thrown overboard by the explosions, others heard an order to abandon ship They were rescued at sea and at Ulithi to board the ship, but Gehres refused them to board calling them cowards and Gehres got the Navy Cross for this, dark day for the Navy.