By Robert L. Durham

The winter of 1863 was a time of general inactivity for the exhausted armies in middle Tennessee. On January 2, 1863, following the bitter, two-day Battle of Stones River, Confederate General Braxton Bragg retreated some 40 miles south from Murfreesboro to Tullahoma. His main concern remained the Union Army under Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, which occupied Murfreesboro as soon as the Rebels evacuated the town. After two days of vicious fighting, the troops of both sides were bled dry, and things remained relatively quiet throughout the first month of the new year.

The Confederate high command did not expect such inactivity to continue for long. It was only a matter of time until Rosecrans decided to advance against them; therefore, they had to stay constantly on the alert for any enemy movement. The Union line stretched in a semi–circle from Lebanon through Murfreesboro to Franklin, with the Southern position roughly parallel to it. The Confederate line was twice the length of the Union, which meant that many more cavalry pickets were required for adequate protection. With that in mind, General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Confederate Department of the West, ordered most of the cavalry in Mississippi to reinforce their fellow Southerners in Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, chief of cavalry in Mississippi, immediately began preparations to move his division northward.

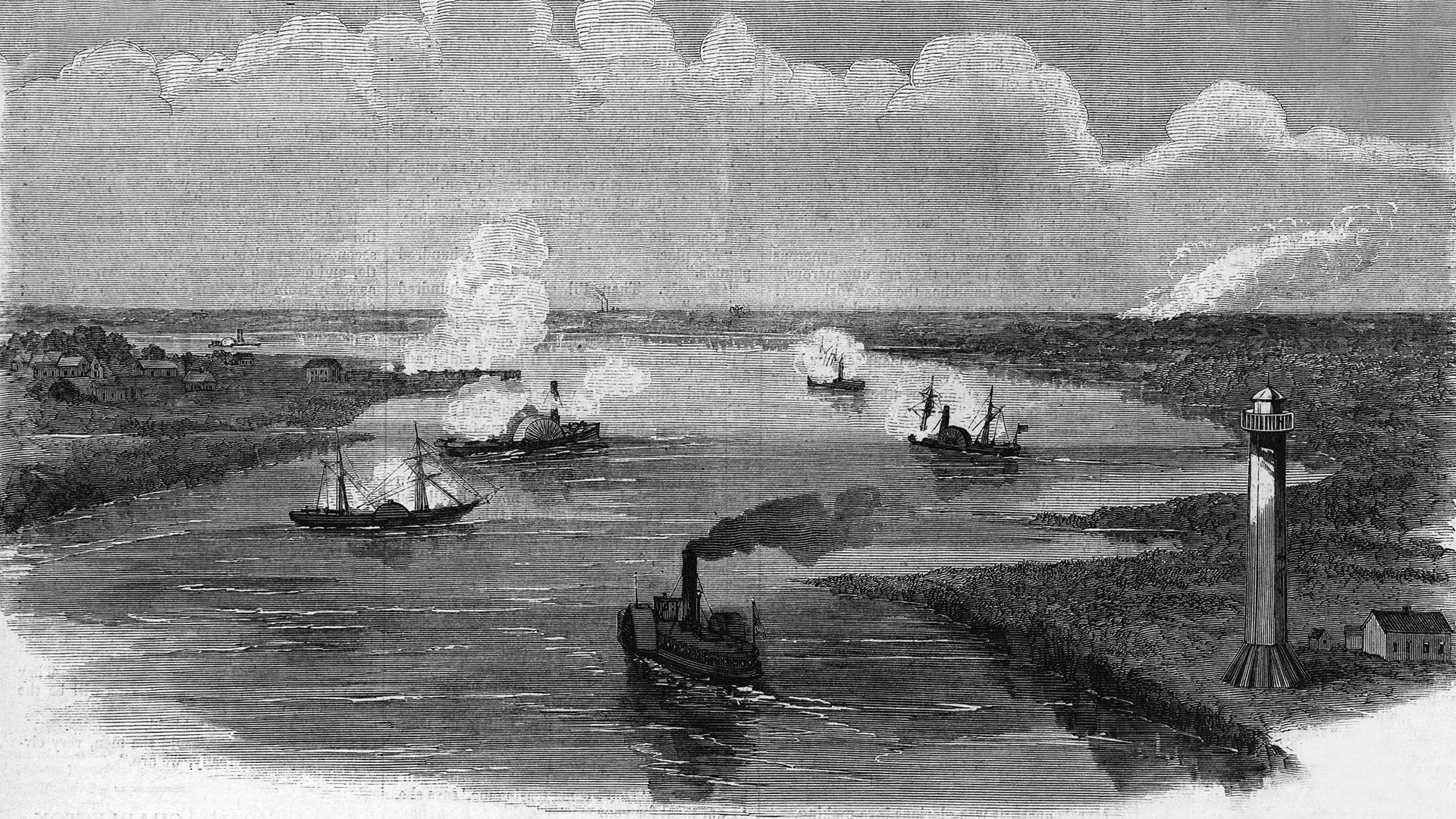

Surprise Attack at Fort Donelson

While awaiting the arrival of reinforcements, the Confederate cavalry in Tennessee was far from idle. Near the end of January, newly minted Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, with his own cavalry brigades and another commanded by Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, made a long swing around the Federal right into northern Tennessee. On February 2, they made a surprise attack on Fort Donelson, site of a crushing Confederate defeat almost exactly one year earlier. The assault was beaten back by the garrison of the fort, but the daring raid made Rosecrans more than a little nervous. If Confederate horsemen could ride with impunity through the heart of occupied Tennessee, they could just as easily gallop into his rear, disrupting his supply and communication lines.

On February 17, the Southern troopers returned from the Fort Donelson raid. Wheeler took up position covering the Confederate right flank and gave Forrest the responsibility of protecting the left. Forrest immediately established his headquarters at Columbia and set up picket posts south of Franklin. The next day these outposts beat back a Union reconnaissance sent from Franklin, preventing the blue-clad soldiers from gathering much-needed strategic information.

On February 17, the Southern troopers returned from the Fort Donelson raid. Wheeler took up position covering the Confederate right flank and gave Forrest the responsibility of protecting the left. Forrest immediately established his headquarters at Columbia and set up picket posts south of Franklin. The next day these outposts beat back a Union reconnaissance sent from Franklin, preventing the blue-clad soldiers from gathering much-needed strategic information.

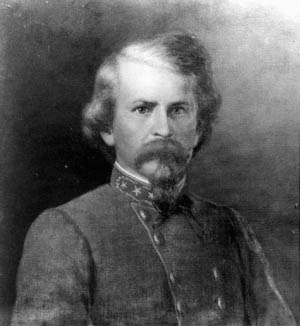

On February 20, Van Dorn arrived in Columbia with three veteran brigades of cavalry. He was a bold and impulsive leader, particularly suited to large cavalry commands. At the end of December, he had led one of the most successful cavalry forays of the war, a lightning raid on Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s base of supplies at Holly Springs, Miss., which delayed Grant’s crucial campaign against Vicksburg. Van Dorn arrived in Tennessee eager for opportunities to earn new glory.

Bragg gave Van Dorn’s command two more brigades to make it equivalent to Wheeler’s cavalry corps. Now commanding five brigades—those of Brig. Gens. Forrest, Frank C. Armstrong, George B. Cosby, W.T. Martin, and Colonel John W. Whitfield—Van Dorn assumed responsibility for the Confederate left. He moved quickly to establish outposts near Franklin and Triune and advanced his headquarters from Columbia to Spring Hill, 12 miles south of Franklin. The Southern pickets were pushed so close to the Union lines that skirmishes became a daily routine.

The scanty information Rosecrans was receiving gave him the false impression that his cavalry was now outnumbered by at least 5-to-1. There was some fear that Van Dorn had also brought an infantry division from Mississippi. Actually, Rosecrans’s cavalry of 8,000 faced roughly 15,000 Confederate troopers. Rosecrans was convinced that the build–up of enemy forces foreshadowed a movement in strength against Franklin. To counteract this supposed threat, he ordered infantry reinforcements down from Nashville. The next day these regiments, under Colonel John Coburn, marched south to Brentwood. On March 2, Maj. Gen. Charles C. Gilbert, the Union commander at Franklin, received false intelligence that Van Dorn and Wheeler had combined forces. He immediately ordered Coburn to march to Franklin. Coburn started at once, arriving that night.

Two-Fold Mission: Gather Intelligence and Supplies

On the evening of March 3, Rosecrans ordered division-strength expeditions from Murfreesboro. Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds was directed to move against Readyville, Brig. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan against Unionville, and Brig. Gen. James B. Steedman against Chapel Hill. At the same time, Gilbert was instructed to send an infantry brigade and a cavalry force south out of Franklin. They were to march down the Franklin-Columbia Pike to Spring Hill, where they would divide, one party going toward Columbia and the other to the Lewisburg Pike, where they would rendezvous with Steedman’s division. They had a two–fold mission: to ascertain what force the enemy had in their front and to collect much-needed forage (a wagon train was provided for this purpose).

Gilbert’s troops were scattered throughout Franklin, so he decided to send Coburn’s brigade. Having just arrived the night before, the brigade was described as “compact and ready to move.” Coburn’s infantry consisted of the 33rd and 85th Indiana, the 19th Michigan, and the 22nd Wisconsin, all untested in battle. To this force, Gilbert added the 124th Ohio Infantry of Colonel William P. Reid’s brigade and cavalry detachments from the 4th Kentucky, 2nd Michigan, and 9th Pennsylvania.

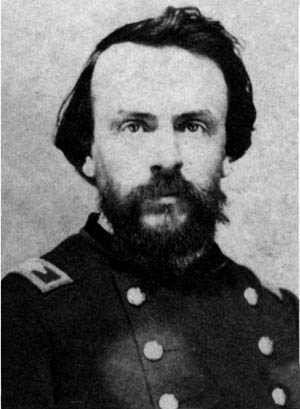

The use of Coburn’s brigade enabled Gilbert to ready a reconnaissance with no delay, but it is doubtful that it was a wise decision. Coburn had never served under Gilbert—in fact, he had just reported to him—and the reinforcements from Gilbert’s division had never served with Coburn. All would be fine if the expedition went smoothly but, in the event of trouble, Coburn would have to trust and be trusted by unfamiliar men.The next morning, March 4, Colonel Thomas J. Jordan, commander of the 600 cavalry assigned to Coburn, suggested that they take an artillery battery along. Coburn reluctantly agreed, and Jordan galloped to Gilbert’s headquarters to obtain the battery. Gilbert assigned Captain Charles C. Aleshire’s 18th Ohio Battery of six rifled Rodman guns to join the column. Finally, at about 9 am, Coburn’s force departed. Altogether, it was almost 3,000 strong. The infantrymen were in light marching order, their blankets rolled over their shoulders. All were in high spirits, believing that they were only going on a foraging expedition. The weather was cool and favorable, and the force made good time traveling down the paved turnpike.

At 10:30, four miles south of Franklin, a large number of mounted men augmented by a battery of artillery were seen in Coburn’s front. This was the Confederate cavalry division of Brig. Gen. William H. “Red” Jackson, approximately 2,800 men, which Van Dorn had sent out on a forced reconnaissance from Spring Hill. Northern intelligence had led Coburn to believe that there would be no enemy artillery, and the presence of such a battery came as an unpleasant surprise. He ordered the four artillery pieces traveling with his advance to unlimber on the east side of the Franklin-Columbia Pike and open fire. The Confederate gunners quickly replied. Coburn deployed his cavalry and infantry on both sides of the road and sent for the section of artillery with the wagon train, having them deploy and open fire from the right side of the turnpike.

Artillery vs. Artillery

The artillery of both sides thundered away at each other for an hour, with neither side delivering or taking significant losses. Meanwhile, Coburn advanced part of his cavalry and three regiments of infantry. The Confederates fell back and moved to the east, trying to outflank the Union troops. Coburn ordered his own men to fall back to their original position and sent a cavalry detachment to stop the Southern flanking force. The artillery section on the right of the Columbia Pike was sent over to the left. During this movement one of the cannon broke an axle tree, putting it out of action.

Coburn reported the skirmish to Gilbert, requesting permission to send the wagon train back to Franklin. He commanded Lieutenant Edwin I. Bachman, assistant quartermaster, to turn the train back, saying that a cavalry force threatened their left. As soon as Bachman got the train turned around, he received a conflicting order to turn around again and advance, then still another order to take the train back to Franklin. Thoroughly confused, Bachman moved the train to within sight of town, where he received still another order to halt and fill the forage wagons.

The Southern troopers eventually pulled back and Coburn advanced to the former Confederate position, where he vainly awaited orders from Gilbert. Justifiably worried about being cut off from Franklin, Coburn sent another note explaining the situation with the Rebel flanking force and asking, “What shall we do? I think we can advance, but there will be at once a force in our rear.” The only instructions he received from Gilbert were permission to send back the forage wagons and a pointed reminder “that he had quite a large margin and a wide discretion.” Coburn interpreted this to mean that he should continue his advance. After sending new orders to Bachman to send the forage wagons back to Franklin and bring the 40 ammunition and supply wagons back to the front, Coburn moved his troops forward a few miles, where he halted for the night.

From his campground, Coburn sent a final request to Gilbert, again stating the danger of being outflanked and pointing out that he did not have sufficient force to prevent it. Having resigned himself to continuing toward Spring Hill in the morning, he ended the letter with a request for more artillery ammunition and a replacement for the Rodman gun that had been sent back for repairs.

Gilbert, considering Coburn’s reports “wild and extravagant,” sent Captain Thomas W. Johnston, “a man of cool judgment,” to assess Coburn’s position. Johnston examined the scene of the skirmish and concluded that the Confederate force opposing Coburn consisted of less than 1,000 cavalry. He reported Coburn as being “in a good deal of doubt as to the intentions of the enemy, and not over-confident.” Gilbert decided that there was no reason to change his original orders. He did, however, send Coburn a new supply of artillery ammunition and the cavalry some new Burnside breech-loading carbines.

“My Orders Are Imperative, and I Must Go On or Show Cowardice.”

The next morning, two 12-year-old black youths were brought to Coburn’s headquarters. They were servants who had fled from the Confederate Army, and they reported that Van Dorn’s main force was close by and advancing toward Franklin. This information convinced Coburn that the enemy force was considerably larger than his own. He sent the two escaped slaves, with a mounted escort, back to Gilbert. Then, after studying his orders, he remarked to Bachman, “My orders are imperative, and I must go on or show cowardice.” Upon being asked what he intended to do, he said, “I am going ahead; I have no option in the matter.”

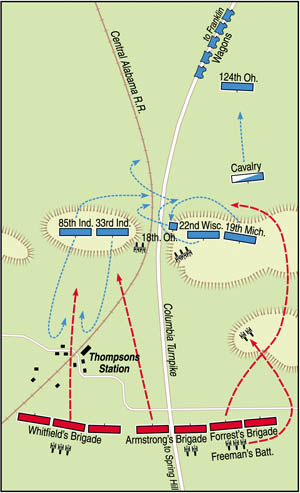

Ordering Jordan to send cavalry detachments to watch two roads on the flanks, Coburn delayed the beginning of his advance until they could get into position. At 8 am, the Union column was again moving forward and the cavalry advanced as skirmishers, forcing the Confederate pickets steadily back. The countryside was wooded and hilly. The Franklin-Columbia Pike wound through the hills, roughly parallel and to the east of the Nashville & Decatur Railroad that ran from Franklin to Columbia. Both the pike and the railroad ran in a southwesterly direction. Three-quarters of a mile north of Thompson’s Station, the pike cut to the south away from the railroad. At the depot, the pike and railroad were separated by 300 yards of open field. Thompson’s Station was a small hamlet consisting of the depot, a school, a church, and a few residences. Fifty yards north of the depot was a wooded hill, the land between being flat, marshy, and open. East of the pike was another tree-covered hill. South of Thompson’s Station lay open fields for 200 yards. A stone fence and a gully ran between the railroad embankment and Columbia Pike south of the open land.

Van Dorn had three brigades of his cavalry dismounted and in line of battle across the hills south of Thompson’s Station. On the left were the two brigades of Jackson’s division under Whitfield and Armstrong. Whitfield’s Texas Brigade was in position on the hill that ran between the railroad and the Columbia Pike, with two guns of Captain Houston King’s 2nd Missouri Battery posted on each flank. East of the pike, on the next hill in line, were the troopers of Armstrong’s brigade. To the right of them were two regiments and a battalion of Forrest’s Tennessee brigade, with the two four-gun batteries commanded by Captains S.L. “Sam” Freeman and John Watson Morton, Jr. The Tennesseans were in a valley with a cedar-covered knoll to their front. Forrest’s other two regiments were some two miles to the east, guarding the Lewisburg Pike.

The three Confederate cavalry brigades numbered roughly 4,400 men, but since approximately a quarter of the troopers were detailed as horse holders, there were about 3,300 in line. At least one regiment, the 9th Texas, assigned its unarmed men as horse holders. The Texas Brigade and the 3rd Arkansas of Armstrong’s brigade had previously served as infantry at the bloody Battles of Iuka and Corinth, Miss. Coburn was about to run into something new to his experience. Infantry, with its greater firepower, could normally push aside the lighter armed cavalry, even when outnumbered. However, the new breed of Confederate cavalry developing in the West was writing a new chapter in Civil War cavalry tactics. Under leaders such as Van Dorn and Forrest, the Southern horsemen combined the mobility of cavalry with the striking power of veteran infantry. These men would not easily be pushed aside.

Artillery in the Thick of the Trees

Coburn was ready for any eventuality as he moved south on the Columbia Pike. His cavalry, with one of the Rodman guns, led the column, followed by an infantry regiment, the other four guns, and three more infantry regiments. The supply and ammunition wagons followed, guarded by the 124th Ohio Infantry.

As the Union cavalrymen started appearing in the hills north of Thompson’s Station, Van Dorn ordered Jackson to advance Whitfield’s brigade, dismounted, to the stone wall in front of his position, with orders not to show themselves. There was a church near the stone wall, and the first regiment kept behind it to conceal their presence from the enemy. When they reached the wall, they filed off to form a battle line. The other three regiments were equally cautious, and the Federals spotted none of them. The trees masked the guns of King’s battery on the hill behind, and Forrest’s brigade was hidden by the hill in its front. The only forces visible to the Union scouts were a few skirmishers.

The Texans of Whitfield’s brigade were still getting into position when the Union column appeared on the pike, north of the depot. Coburn, in the advance with his cavalry, pointed out the hills on both sides of the pike north of Thompson’s Station, saying to Jordan, “On these two points I thought the enemy were going to make a stand.” Just then, a gun in King’s battery fired on the approaching Union column, showering them with dirt and stones but doing no real damage. Quickly, the Federals took cover beside the road, sheltered behind the hill on the east.

The Texans of Whitfield’s brigade were still getting into position when the Union column appeared on the pike, north of the depot. Coburn, in the advance with his cavalry, pointed out the hills on both sides of the pike north of Thompson’s Station, saying to Jordan, “On these two points I thought the enemy were going to make a stand.” Just then, a gun in King’s battery fired on the approaching Union column, showering them with dirt and stones but doing no real damage. Quickly, the Federals took cover beside the road, sheltered behind the hill on the east.

Coburn galloped back to deploy his infantry and artillery, sending a two-gun section across the railroad to take position on the hill north of Thompson’s Station and the other three guns to the top of the hill east of the pike. He dispatched two infantry regiments to support each position, the 33rd and 85th Indiana to the right, the 19th Michigan and 22nd Wisconsin, with a detachment of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry, to the left. Meanwhile, the Confederates were responding to Coburn’s maneuvers. The last regiment of Whitfield’s brigade lined up behind the railroad embankment out in front of the other troopers. This gave them a more direct field of fire against the Indiana regiments.

On the Confederate right, Forrest ordered his men to move forward and form a new line on the heights in front. The knoll was higher than the one on which the Union left was anchored, and a heavy growth of cedar effectively concealed Forrest’s position from view. Forrest took advantage of the terrain to move his artillery, unseen by the enemy, into a position where they could enfilade the Federal forces. When Forrest’s guns opened fire on the Union lines, a startled Coburn could not tell where the shells were coming from.

Coburn sent Jordan forward to ascertain the location of the enemy artillery. Just as Jordan sighted the battery, one of the guns fired a shell directly at him. He leaned over to his left as far as possible, and his experienced horse also tried to avoid the shot, bending down until its stomach almost touched the ground. The shell passed over Jordan’s head, hit a tree stump 50 yards behind him, and bounced high into the air. The subsequent explosion did no damage.

“That Command was Obeyed About as Quickly as Any Command Ever Was”

Jordan reported back to Coburn, who was with the Indiana regiments on the western hill. The main Confederate line was still concealed, the only enemy forces observable from Union lines being the Rebel artillery and the skirmishers at Thompson’s Station and along the railroad embankment. Three companies of the 33rd Indiana were sent to dislodge the enemy sharpshooters in and around the buildings at the depot. The Union infantry advanced under a cross-fire from the two enemy batteries and the skirmishers. The Confederates retreated into the fields south of the depot, and the action on this section of the battlefield settled down to an artillery duel for the next half hour. The Union artillery concentrated on a section of King’s battery near the turnpike, but initially overshot their mark. A correspondent for the Mobile Advertiser and Register, who was present at the battle, reported: “They then changed the range of their rifled pieces so as to command the hill upon the left of the pike opposite our battery, and threw several shells with remarkable precision into the position occupied by Generals Van Dorn and Armstrong, and staff, and your correspondent. We quickly ‘changed our base,’ and spread out so as to avoid making a target of the party.”

East of the Franklin-Columbia Pike, the Confederate guns were firing on the Federal left. They drove off the detachment of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry and forced the 19th Michigan Infantry to fall back behind the crest of the hill. Harvey Reid, a young member of the 22nd Wisconsin, described his first experience under fire: “Suddenly the report of a cannon was heard in front, and the cavalry whirled their horses and dashed down the pike. This report was immediately followed by another one when whirr-zoo-o-o—came a shell close along our right parallel with the pike. It was so near that the whole regiment involuntarily crouched to the earth, the command was immediately given ‘Over the fence and lie down!’ and that command was obeyed about as quickly as any command ever was.”

The three guns of Aleshire’s 18th Ohio Battery retreated to the pike. Forrest’s dismounted cavalry then joined the attack, firing on the foot soldiers of the 22nd Wisconsin under Colonel William L. Utley. Van Dorn ordered Forrest to get behind the Union force and cut them off from Franklin. Forrest placed Colonel James W. Starnes of the 4th Tennessee in command of his troops on this section of the field and raced off with his escort to gather up the two regiments he had left on outpost duty on the Franklin-Lewisburg Pike.

Meanwhile, the 22nd Wisconsin Infantry, never before in combat, stood alone against half a brigade of dismounted cavalry and part of an artillery battery. The Wisconsin foot soldiers, in line on the forward slope, moved back to the crest of the hill previously vacated by the artillery. The 19th Michigan had also moved up to the crest, and the 22nd fell in on their left. The height of the Union-held hill was lower than that held by Starnes’ Confederates. The difference exaggerated the men’s natural tendency to fire too high, and most of the Confederate bullets passed over the heads of the Federal troops.

The green troops from Wisconsin handled themselves admirably. According to their commander, Utley, the same could not be said of some of the officers of the regiment. “Upon the very first fire of the enemy,” Utley reported, “[the officers] retreated to a safe position, and remained there during the entire engagement on the hill, never once offering to assist in rallying the stragglers or seeing to the wounded. During the engagement the lieutenant-colonel, from his safe retreat, annoyed me by sending word to me to retreat.” This must have had an unsettling effect upon the men, but they maintained control of this part of the field.

Enemy Artillery Shells Continued to Rain Down on the Troops Around Thompson’s Station.

Colonel Henry C. Gilbert, the commanding officer of the 19th Michigan, experienced a similar problem with one of his company commanders. According to Gilbert, Captain Elisha B. Bassett of Company B, who had been unsuccessfully attempting to resign for several months, “took shelter behind a large tree 15 or 20 yards in the rear of our line. I found him there & asking what he was doing there & why he was not with his company he replied that he could not take any part in the fight, that I must not depend upon him for anything, that the Lieut could command the Company & begged me to excuse him.” Refusing to obey Gilbert’s direct orders to resume his command duties, he eventually commandeered a cavalry horse and rode off to Franklin, leaving the command of his company in the capable hands of Lieutenant Samuel Hubbard.

On the Union right, events were about to come to a head. Enemy artillery shells continued to rain down on the troops around Thompson’s Station. To remedy this, Coburn decided to capture or drive away King’s battery. He was still unaware of the Confederates hidden behind the stone wall. Whitfield’s men had strict orders to keep their heads below the level of the fence, but the officers had to keep reminding the men not to show themselves. One impetuous member the 6th Texas managed to make a hole in the fence, through which he watched the Union soldiers approach. Another soldier appropriated the peephole and refused to yield, leading to a fistfight with the first Texan. Both parties were arrested and taken to the rear.

Coburn ordered the two Indiana regiments to advance to the depot and cross the railroad track to attack the enemy battery. The Hoosiers responded gallantly, moving down the forward slope of the hill and across the open field to the depot in the face of a withering crossfire from the Confederate artillery. Everyone who saw the charge was impressed. Jordan left behind an eloquent account: “The column was formed, and moved from its position behind the guns over the crest of the hill and down into the valley below, prepared to charge the battery, while the enemy’s guns thundered their shells upon it from front and flank. It bravely withstood the shock, and moved steadily forward, though its track through the fields could be plainly marked by the human mile-stones left in its rear.”

1,000 Confederate Cavalry Marched Towards the Union’s Rear

Van Dorn, seeing where the Union assault would fall, ordered Armstrong to send a regiment to the aid of Whitfield’s Texans. Colonel Samuel G. Earle’s 3rd Arkansas moved rapidly across the turnpike to join their fellow Westerners along the stone wall. Meanwhile, the Federals reached the depot and, as they crossed the railroad tracks, came under fire from the Confederates hiding behind the stone fence. Taken completely by surprise, the attackers halted in confusion as the men sought shelter in and around the depot buildings and behind the railroad embankment.

Amid the confusion, Coburn received word that 1,000 Confederate cavalry had been sighted moving up the Franklin-Lewisburg Pike toward the Federal rear. This was Forrest’s flanking force. Coburn recalled the Indianans and ordered Jordan to bring two companies of cavalry forward to support their retirement. Jordan, apparently misunderstanding the order, rode off to hold the road open for the retreat of the whole expedition. As the Union infantry fell back across the field toward their old position, the Confederate troopers moved out from behind their stone wall and followed. Southern artillery continued its shelling.

The situation was rapidly deteriorating for Coburn’s command. The three guns of Aleshire’s artillery battery that had fallen back from the hill on the east remained on the pike but out of action. Lieutenant Hamlet I. Adams, Coburn’s acting assistant adjutant general, tried to convince Aleshire to open fire with canister on the Rebel troops pursuing the Indianans, but Aleshire refused, claiming that he was low on ammunition. He kept his guns limbered, prepared to retreat at the first sign of danger.

Coburn ordered Bachman to start the ammunition wagons back to Franklin. Bachman was prompt in executing the order, but unfortunately took the train escort, the 124th Ohio, with him. Coburn’s only reserve marched off the field in the middle of the battle. In the excitement, Coburn had apparently forgotten they were there and never ordered them forward to his assistance. Making an already bad situation worse, Jordan took it upon himself to save the three Union Rodmans on the pike and ordered their premature retirement from the field. Aleshire, no doubt grateful for the interference, accepted the unauthorized order without question. When the retreating Union infantry regained the summit of the hill, they found much of their artillery support gone, headed back toward Franklin.

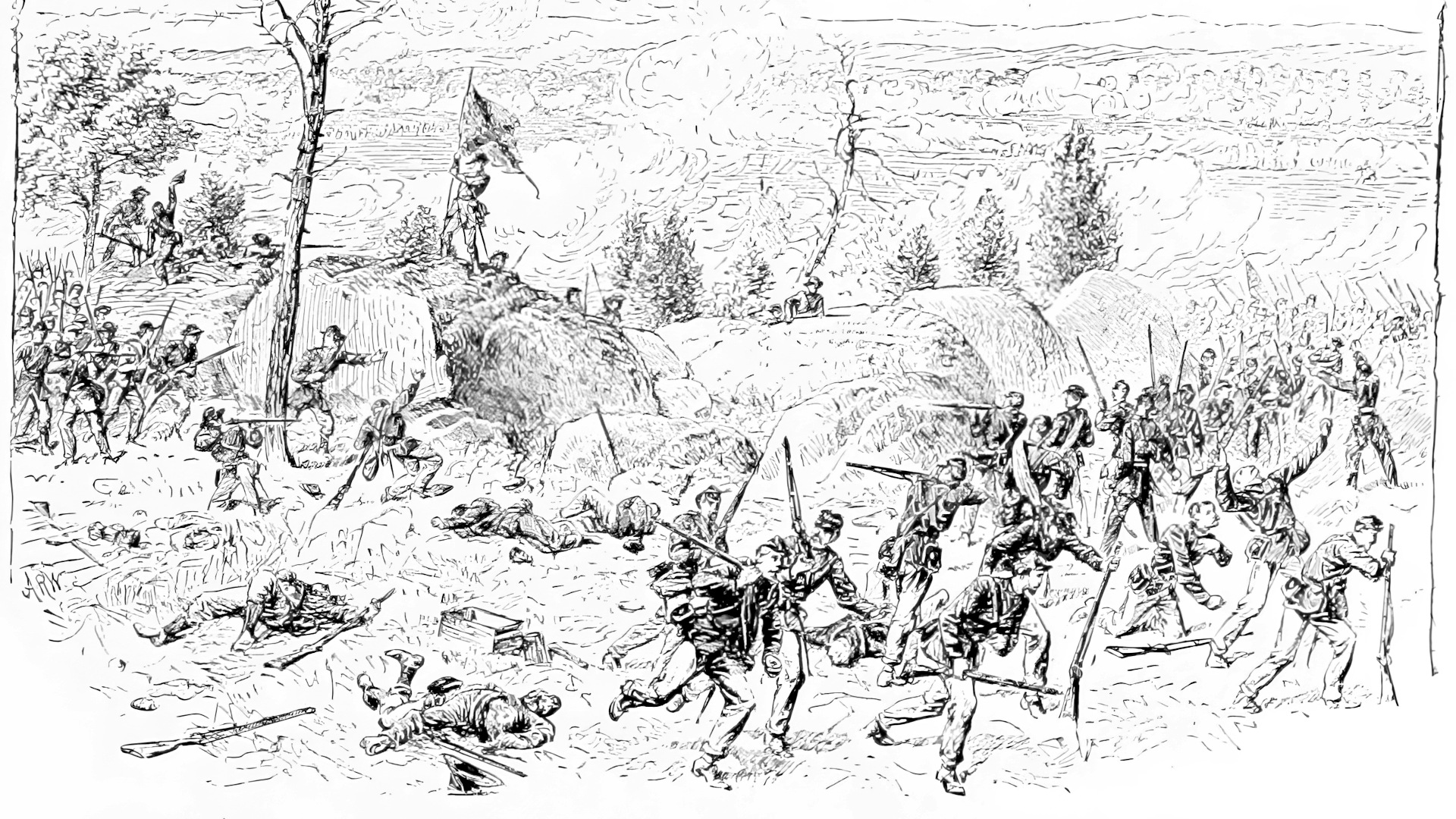

Whitfield’s Texans and Earle’s Arkansans chose this moment to charge up the slope toward the Union position. The Federals waited behind the crest and, as the Southern troopers swarmed over the summit, countercharged with bayonets fixed. They drove the Confederates back down the hill and across the field, all the way to the depot. When the onrushing Federals reached the depot, they found the guns of King’s battery waiting for them. The Confederate troopers rallied around their artillery and the Union infantry was pushed back across the field, retreating to the top of the original hill.

75 of the 225 Men Were Killed

During one of the attacks, three privates from Company E, 3rd Texas Cavalry—Lon Cartwright, Drew “Bully” Polk, and Hugh Leslie—moved forward as part of Whitfield’s attacking line. When Cartwright saw a Yankee taking aim on Polk, he tried to shoot the enemy skirmisher first, but his rifle misfired. The Federal shot Polk in the head, killing him instantly. Too late to save their friend, Leslie avenged his death by killing the Union soldier.

Twice the Texas and Arkansas troopers charged up the hill, only to be forced back to the railroad. The loss in Whitfield’s Texas Brigade was frightful. The 1st Texas Legion under Colonel John H. Broocks lost 75 of 225 men, with one company losing half its number. The loss was especially severe in the Legion’s officer corps, with Captain James A. Broocks, the brother of the commander, being one of those slain. The Southern troopers formed a third time and again advanced under galling fire to the hilltop, and this time they would not be driven off.

Already facing twice their number of dismounted troopers, the Indiana infantrymen had worse awaiting them. Coburn could see the Rebel cavalry of Armstrong’s brigade mounting up and forming a column on the Franklin-Columbia Pike. If they attacked down the pike, the Federal command would be fatally split. Coburn sent orders to the 19th Michigan on the other side of the pike to cross over and extend the left flank of his Indiana soldiers. He then ordered his right-flank regiment to the left of the 19th Michigan, shifting his line closer to the pike in an effort to protect his only line of retreat.

The 19th Michigan responded quickly, moving across the pike and railroad, leaving the 22nd Wisconsin to face Starnes’ Confederates alone. During a temporary lull in the firing, Lt. Col. Edward Bloodgood decided that it would be a good time to abandon the fight. While Utley was encouraging the men on the left of the regiment, actually joining them in the firing line with a rifle, Bloodgood ordered the right-hand companies to retreat. When Utley saw the right half of his regiment marching down the hill, led by Bloodgood, he ran after them to try to stop their retreat. The left of the regiment, seeing their colonel running down the hill after their departing comrade, understandably panicked. They abandoned their own position, streaming down the hill to the valley below, where Utley finally got them stopped and reformed along the railroad track.

The Confederates took advantage of the confused situation, their dismounted troopers and two guns of Freeman’s battery moving forward into the vacated Union position. Utley ordered his men to fix bayonets and attempt to retake the hill. When he reached the right of the line, he looked back in astonishment to see Bloodgood leading the left half of his regiment up the pike toward Franklin—resolutely away from the enemy.

With Half His Men Dead, Utley Abandoned His Plans

The section of Aleshire’s battery stationed west of the pike chose this same moment to abandon their position. Harvey Reid, one of the men who Bloodgood led away from the battle, recalled: “Just as we reached the pike some one behind shouted, ‘Get out of the road, the battery is coming,’ and we could hardly get off the road, when the two guns which had been on the right, dashed by, every one of the horses being on a wild gallop. It was now too late to think of rejoining them [the remainder of the brigade] and we kept on down the pike, firing as we ran.”

With half his regiment gone, the frustrated Utley abandoned all thought of retaking the hill and instead moved the remnant of his command to support the Indiana and Michigan troops. Coburn’s only remaining reserves were the remnants of the four regiments of his own brigade. As Armstrong’s brigade dismounted and prepared to charge, Coburn formed his men in the best defensive position he could. The 33rd Indiana formed in line facing south, with two companies thrown far out to the right to protect the flank. The 19th Michigan formed on the left and at right angles to the 33rd, facing east toward the turnpike and railroad. Next to them was the 85th Indiana, then the remainder of the 22nd Wisconsin. The left of the 19th Michigan and the right of the 85th Indiana were barricaded inside a schoolhouse.

The Federal infantry thought their cavalry had abandoned them, but Jordan’s troopers were still deployed in the fields east of the pike, holding the road open for the infantry’s retreat. Unfortunately for Coburn, even if he had known Jordan was holding the road open for him, retreat by that route was now impossible—Armstrong’s Confederates blocked the road.

The Federal infantry thought their cavalry had abandoned them, but Jordan’s troopers were still deployed in the fields east of the pike, holding the road open for the infantry’s retreat. Unfortunately for Coburn, even if he had known Jordan was holding the road open for him, retreat by that route was now impossible—Armstrong’s Confederates blocked the road.

At this juncture, Forrest’s flanking column appeared. Tough and disciplined, the men dismounted and moved against Jordan’s cavalry, who fired on them from behind stone fences. The Southern troopers made two charges. At the beginning of the second, Forrest’s horse, Roderick, was badly wounded. Forrest exchanged horses with his son, 17-year-old Lieutenant Willis Forrest, who took the injured animal to the rear. There, the horse holders unsaddled and unbridled him. Roderick, accustomed to following Forrest around like a faithful dog, broke free and ran back after the general. Jumping three fences on the way, the old war horse reached his master, only to receive a fatal wound.

After 15 hard-fought minutes, Jordan’s men were forced from the field. Harried by cavalry sent in pursuit, Jordan retreated toward Franklin. Forrest paused to reform his men in the fields east of the turnpike, while Whitfield’s and Armstrong’s brigades launched their own attack against the remaining infantrymen of Coburn’s brigade. The 33rd Indiana faced Whitfield’s Texans and Earle’s Arkansas regiment and gallantly held them off. One volley killed Earle, blowing off half his head, and downed the entire 3rd Arkansas Color Guard. Seventeen-year-old Alice Thompson rushed from her residence outside the village, picked up the fallen flag, and defiantly waved it, rallying the faltering Southerners.

The 3rd Texas also lost its flag. When the staff was broken by a shot, the color bearer snatched it up and ran off. Unfortunately, when he was making his escape through a plum thicket, the flag was torn into ribbons and left hanging on the bushes. Meanwhile, the Union troops on the left of the 33rd Indiana were being attacked by Armstrong’s men. The fighting was at close quarters, especially fierce around the schoolhouse. One Southern soldier was shot by an 85th Indiana infantryman from a window as he was trying to break in the front door. During the hand-to-hand fighting, the 19th Michigan captured the battle flag of Armstrong’s brigade.

Union Forces Almost Completely Surrounded

The Union troops forced the Confederates back, but they were running low on ammunition. The colonel of the 33rd Indiana sent a detail to find the missing wagon train, but the ammunition wagons were gone. There would have been no time to bring back any ammunition even if they had found the train—the Confederates were attacking the hill again, this time reinforced by Starnes’ men of Forrest’s brigade.

The Federals could not hold out much longer. Forrest’s two flanking regiments faced them across the valley. Morton brought up his battery, commanding the new position taken by the Federals, and at the same time cut off their retreat toward Franklin. The Union forces were almost surrounded. To the north was Forrest, to the east were Armstrong and Starnes, and to the south was Whitfield. As if the outlook were not already bleak enough for the Federals, the Confederates now received reinforcements. General Cosby arrived with his Mississippi and Kentucky brigade. He sent two regiments to support Whitfield and two to attack Coburn on the west, making the encirclement complete.

Coburn ordered his men to fix bayonets and prepare to charge Forrest’s position, but Forrest anticipated him and began his own attack. His Tennesseans moved forward against a heavy enemy fire. Lieutenant John Johnson was killed while at the front with the colors. Private Clay Kendrick of Colonel J.B. Biffle’s cavalry regiment caught the flag as it was falling and held it aloft until his arm was broken with a bullet. The fight was vicious, and Forrest lost two of his best officers, Captain Montgomery Little, the commander of his escort, and Lt. Col. Edward Buller Trezevant, in command of the 10th Tennessee Cavalry.

It was apparent to the Northern commander that further resistance was useless. Nearly surrounded and almost out of ammunition, any attempt to escape would be senseless. Before Forrest’s attacking cavalrymen reached his line, Coburn gave the order for his men to surrender. The Southern commanders instructed their men to cease fire, and the cavalrymen quickly complied, but the guns of King’s battery continued to blast away at the Union position. Couriers were hurriedly sent off, informing the artillerymen of the surrender. These guns, too, fell silent.

While Coburn’s brave troops fought against hopeless odds, other Union forces back at Franklin stood by helplessly, waiting for orders to go to their assistance. Early in the day, Colonel Emerson Opdyke had urged Gilbert to send support to Coburn, but Gilbert delayed until heavy firing indicated serious trouble, when he ordered Opdyke to advance. The 125th Ohio Infantry moved rapidly to the front until it met the retreating force and discovered that the movement was too late. The 125th Ohio was the only unit to attempt to aid Coburn’s command. The other troops stood at their guns around Franklin and listened to the rattle of musketry and the roar of artillery, but Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, commander of the Army of the Ohio, would not give the order to assist.

2,500 Men; 1,446 Casualties

The Union captives were gathered up and marched to Columbia. According to the newspaper correspondent from Mobile, “The commander of the Yankee forces says that yesterday he was directed to advance and occupy this place, but after finding our force returned word that he could not do so as the enemy were too strong for him. His superior then sent word that that was no answer from a soldier, and directed him to advance to day and occupy Spring Hill. The Yankee commander of the surrendered forces did occupy the place this evening with his forces, en route to Bragg! Hurrah for the cavalry victory.”

Of the 2,500 men engaged, the Federals suffered 1,446 casualties, 1,151 of whom were captured. Still, Van Dorn’s Confederate horsemen had not achieved an easy victory. The Southern forces numbered approximately 6,000 men, but only about 3,450 were actively engaged. These men suffered 354 casualties, almost exactly 10 percent of their number.

The ordeal of the Union captives did not end when they reached Columbia. After a few days’ stay, at short rations, they were marched through Shelbyville to Tullahoma. The two-day march from Shelbyville was grueling—the weather had become cold and rainy and the roads turned into quagmires. The prisoners often had to wade waist-deep through icy streams. When they reached Tullahoma, their overcoats and blankets were taken from them and they were loaded aboard open railroad cars and sent through Chattanooga and Knoxville to Richmond. The rains turned to snow, and 18 inches of snow lay on the ground when they finally arrived at Libby Prison. Eighty-five men died from the effects of the journey and their subsequent confinement before they were exchanged two months after their capture.

Ironically, the other Federal expeditions that had been sent out from Murfreesboro were successful in accomplishing their missions. Reynolds’s division pushed as far east as Readyville and Auburn before returning. Steedman’s division raided Chapel Hill, while Sheridan’s division sent a cavalry brigade as far south as Unionville, where they routed the Confederate cavalry stationed there. The day after Coburn’s surrender, Sheridan was ordered to advance to Spring Hill in an effort to revenge Coburn’s disastrous defeat, but Van Dorn retreated behind the safety of Duck River.

The prevailing opinion of the Union high command immediately after the disaster at Thompson’s Station was that Coburn had been too rash in attacking the Southern forces. Many in the Union Army shared this attitude. Colonel Francis T. Sherman of the 88th Illinois Infantry, part of Sheridan’s command, was among the troops sent to Thompson’s Station after the battle, too late to be of any help. Sherman wrote a letter home to his father, referring to the calamity as “one of the most stupid and disgraceful affairs that has happened in a long time.” He believed that “if Coburn had shown a little more grit he could have brought his brigade out.”

The “Evil Genius” of the Indiana Soldiers

Gilbert was at least as much at fault as Coburn, which Rosecrans quickly realized. “The causes of this loss, which was wholly unnecessary, appear to have been want of proper caution on the part of Colonel Coburn to feel his way and keep General Gilbert advised,” Rosecrans reported, “and too much indecision on the part of General Gilbert in either giving orders to Colonel Coburn to retire or going out at once to re-enforce him.” A writer for the Indianapolis Daily Journal used even stronger words against Gilbert, saying, “He has been the evil genius of Indiana soldiers from the first [and] he had better walk into a furnace seven times heated than get into the hands of Hoosiers.” By doing nothing, Gilbert had effectively abandoned Coburn to his fate.

The Union soldiers of the 19th Michigan and 22nd Wisconsin not captured at the Battle of Thompson’s Station, either because they fled, or because they were sick or on detached duty at the time, did not enjoy their respite for very long. Reinforced, they were placed under the command of Bassett and Bloodgood, respectively, and stationed in Brentwood, Tenn. The cowardly Bassett was assigned to man the stockade guarding the railroad bridge over the Little Harpeth River at Brentwood and Bloodgood was stationed in the town itself.

On March 25, Forrest made a raid on Brentwood. True to form, both Bassett and Bloodgood surrendered their commands, giving only a token resistance. After being exchanged, Bassett was dismissed from command due to cowardice at Thompson’s Station. Bloodgood was court-martialed six months after the battle and also dismissed from the service, but later was reinstated due to political influence. Although disliked intensely by Utley, Bloodgood was popular with most of his men, especially those he led away from Thompson’s Station, and he later redeemed himself as he gained experience. He continued serving until the end of the war, eventually succeeding to command of the 22nd Wisconsin, and even commanded the brigade at times. After the war he joined the Regular Army.

Coburn’s bad-luck brigade would disgrace itself yet again during the Confederate siege of Chattanooga, when many of the troops surrendered to a Confederate raiding force under Wheeler. Fortunately for them, they were paroled on the spot and did not have to spend time in a Confederate prison. The brigade would finally redeem itself during Maj. Gen.William Tecumseh Sherman’s campaign against Atlanta and the March to the Sea. By then, of course, it was too late for the 85 members of the unit who had already perished inside Libby.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments