By Gustav Person

The Union Army’s ambitious Overland Campaign began on May 4, 1864. It was the fourth year of the Civil War, and Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had been brought east to command all the Federal armies and end the war. He immediately planned a series of simultaneous offensives to deny the Confederates the ability to redistribute their forces to meet the attacks. Grant knew that Virginia would continue to be the main theater of the war, and he chose to make his headquarters in the field with the Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Facing them were General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

The campaign did not begin well for the Union, with the Army of the Potomac suffering heavy casualties as it fought its way south from the area around Fredericksburg toward Richmond. Grant sidestepped Lee’s army repeatedly, and both armies came to rest at Cold Harbor, eight miles east of the Confederate capital. After the failure of Federal frontal assaults on the morning of June 3, a stalemate ensued as the opposing armies dug in extensively. The armies would remain in place under hot, fetid conditions for the next nine days.

Grant decided to change his strategy. His new target would be the Confederate commercial and transportation hub at Petersburg, 20 miles south of Richmond on the Appomattox River. By capturing Petersburg, Grant could starve the Southerners out of their defenses around Richmond and defeat them on open ground of his own choosing. But to do that, he would first have to steal a march on the Confederates, cross the James River undetected to the south, and capture Petersburg before the Confederates could react.

Grant devised a complex plan that involved combined actions between the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. Army engineers would play a vital role. The Engineer Brigade of the Army of the Potomac had already performed Herculean tasks since the beginning of the campaign, erecting 38 pontoon bridges with an aggregate length of 6,458 feet.

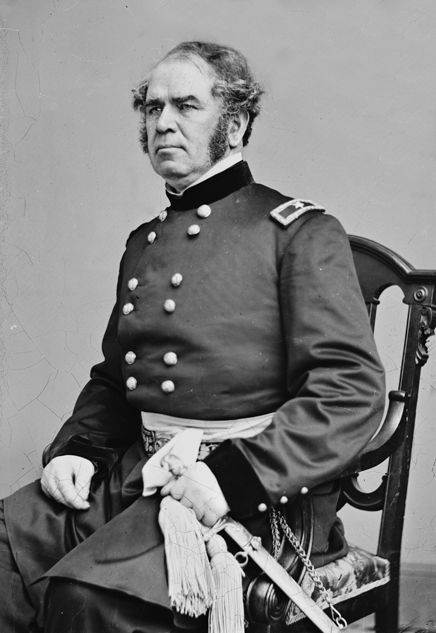

Meade had an efficient force of engineer troops, including Captain George H. Mendell’s United States Engineer Battalion, consisting of four companies. Brig. Gen. Henry W. Benham’s Volunteer Engineer Brigade, like the Regular battalion, had served with the Army of the Potomac since late 1861. It was a seasoned unit of volunteers, originally consisting of the 15th and 50th New York Volunteer engineer regiments. Soon after Chancellorsville in May 1863, most of the 15th New York mustered out of service after their two-year enlistments expired. Its few remaining companies, composed of three-year enlistees, were detailed to behind-the-lines duties. But the 50th New York, commanded by Lt. Col. Ira Spaulding, remained with the Army of the Potomac throughout the war. The 50th consisted of 11 companies, divided into four battalions, with 40 officers and 1,500 enlisted men.

During the Overland Campaign, the battalions were parceled out to support the different corps of Meade’s army. Benham and most of the 15th were at the engineer depot in Washington at the beginning of the campaign. He transferred the 15th and his headquarters to Fortress Monroe when it became the forward engineer base for Grant’s operations. Butler’s Army of the James’ engineer troops consisted of eight companies of the 1st New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment, commanded by Colonel Edward W. Serrell.

On the afternoon of June 6, Grant dispatched two of his aides, Lt. Cols. Cyrus Comstock and Horace Porter, to confer with Butler and apprise him of the impending operation. In late May, Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith’s XVIII Army Corps of the Army of the James had been detached to reinforce the Army of the Potomac and was currently entrenched in the Union line at Cold Harbor. Grant intended for the corps to leave White House Landing on the Pamunkey River, steam 150 miles around the James peninsula, and lead the attack on Petersburg from Bermuda Hundred. Smith would cooperate with the II Army Corps, which would cross the James farther downstream. Comstock and Porter were to select the best crossing point on the river for the pontoon bridge site, choosing a place that would give the Army of the Potomac as short a line of march as practicable, while at the same time being far enough downstream to allow for sufficient distance between it and Lee’s army.

Grant had foreseen the possibility of crossing the James as early as April 15, when he ordered Benham to gather and hold at Fortress Monroe sufficient water transports to tow necessary quantities of bridge-building materials to span the James. At 9 am on June 13, Union forces would begin to disengage from the defenses at Cold Harbor. Grant’s careful planning had already paid dividends when he ordered the pontoon boats upriver around noon on June 4. A total of 150 pontoon boats with attendant bridging equipment had quickly gone to Bermuda Hundred, and additional battalion bridge trains from the 50th New York were ordered south.

Meade’s talented chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys, was directed to draft the operations order. In broad outline, Humphreys detailed that the Army of the Potomac would evacuate Cold Harbor in four coordinated columns. The operation was to begin with V and II Army Corps crossing the Chickahominy River at Long Bridge. Engineers of the 50th New York were detailed to build a 1,200-foot-long pontoon bridge across the watercourse, requiring extensive use of corduroy approaches because of the surrounding swampy terrain. Once over, V Corps turned west to provide screening and blocking and to create the impression that Grant intended to launch an offensive north of the James toward Richmond.

Once in place, V Corps occupied a five-mile defensive position from the White Oak Swamp to Malvern Hill. The 3rd Cavalry Division of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps reinforced Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps for the mission. Simultaneously, VI and IX Corps were to follow separate routes to Jones’ Bridge on the Chickahominy River and continue on to Charles City Court House. A third column, made up of the army’s trains and accompanied by Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s division of United States Colored Troops as a guard force, was to cross the Chickahominy east of Jones’ Bridge.

On June 12, Brig. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, chief engineer of the Army of the James, directed Lieutenant Peter S. Michie to make a detailed reconnaissance of the river crossing areas in the vicinity of Fort Powhatan. Michie selected Wilcox Landing for a ferry site, three-fourths of a mile upstream from Fort Powhatan, and Weyanoke Point for the bridge site, three miles downstream. The width of the river at the latter point spanned 1,992 feet. The landward approaches would require considerable clearage of trees and an extensive trestle ramp. The James was navigable for 108.8 miles from its mouth to Richmond. At Weyanoke Point, the narrow river channel averaged 85 to 90 feet deep, with swift tides that rose and fell three to four feet each day. Michie also selected an entrenched bridgehead position covering the crossing sites. By the evening of June 14, the entire army—less the army trains and the cavalry—had arrived at the bridgehead.

The United States Engineer Battalion moved out in full marching order at 5 pm on June 12, crossing the Chickahominy on the pontoon bridge at Jones’ Bridge laid by the 50th New York. On the far side, they awaited the passage of VI Corps and then marched to Charles City Court House, where they made camp. On June 14, the battalion moved out at 11 am; three hours later it went into bivouac at Weyanoke Point. At 3 pm, the men fell in without arms and proceeded a short distance down the bank, where Weitzel waited with several companies of the 1st New York.

The area was a scene of confusion; nothing had been done toward erection of the bridge. The pontoon material had been transported to Bermuda Hundred in early June, and then, inexplicably, moved back to Fortress Monroe on June 12. It would take another 24 hours to reposition all the equipment at Weyanoke Point. Not to be delayed further, the detachment of 200 engineers sprang into the slimy, muddy, neck-deep water and succeeded in building in one hour an abutment of trestle work some 150 feet long through the soft marshes—arguably the hardest part of the entire project. The battalion then went to work on the opposite shore, with volunteers taking up the work at Weyanoke Point.

Benham arrived around noon from Fortress Monroe with portions of the 15th New York and a number of vessels with bridge materials in tow. He was soon joined by an additional detachment of 220 men and a bridge train of the 50th New York. Major James C. Duane, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac, turned over the completion of the bridge to Benham. As fast as materials could be unloaded from the vessels, they were made into “rafts” of six pontoon boats and rowed into position. The bridge was built simultaneously from both shores by successive rafts.

Most of the three infantry corps began ferrying across the James at Wilcox Landing on the morning of June 14. Major Wesley Brainerd and his battalion of the 50th New York (Companies B, F, and G) had already arrived to repair the wharves. Later that evening, he was ordered across the river to Windmill Point to construct an additional wharf for the use of follow-on troops. Federal officers had gathered a varied flotilla of steamers and ferries to carry the huge army. The 141st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment of II Corps crossed from Wilcox Landing on the Thomas Powell, a steamer that normally cruised the less-troubled waters of the Hudson River.

The ferrying operation required 62 hours to convey the infantry across. The same troops might have marched over the bridge in less than one-fourth the time. About noon, steamers carrying XVIII Corps began to pass Windmill Point en route to rejoin the Army of the James. Smith, commanding the corps, was aboard the leading steamer. The troops marching overland and those moved by water met simultaneously on the James River.

The engineers began assembling the pontoon bridge around 3 pm on June 14, after a further delay to allow the river passage of XVIII Corps past Weyanoke Point. The bridge, completed seven hours later, was 2,170 feet long and used 101 pontoon boats. It was constructed with intervals of 20-foot spans. Planking called chess, laid across balks, provided a roadway 11 feet wide between guardrails. To permit the passage of vessels upstream and downstream, a draw 100 feet wide was incorporated into the bridge. This draw, constructed of pontoon rafts, could be disengaged and floated out with the current to open the draw. To anchor the bridge in the swift current, three schooners were positioned abreast above the bridge and three below.

At the time of the crossing, Grant estimated the combined strength of the Armies of the Potomac and the James at about 115,000 men, even though half of the artillery was sent back to Washington. Although Meade ordered IX Corps to begin crossing immediately, the first troops did not start crossing the bridge until 6 am on June 15, even though the bridge was fully operational at 1 am. Except for five hours on June 15, from 6 am that day until 9:30 am on June 17, the bridge was in constant use—a total of 46 hours. Personnel, animals, and vehicles crossed without incident.

The crossing greatly lifted the morale and spirits of the men who had left the horrid trenches at Cold Harbor and made the hot, dusty march from the Chickahominy. Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman of Meade’s staff asserted, “To appreciate such a sight you must pass five weeks in an almost unbroken wilderness, with no sights but weary, dusty troops, endless wagon trains, convoys of poor wounded men, and hot, uncomfortable camps. Here was a noble river.” As the 7th Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment reached the James, its brigade band serenaded them with “Ain’t I Glad to Get Out of the Wilderness,” which dramatically summed up the feelings of the entire army.

With all the troops safely across the river, the bridge was disassembled on June 17 and its components towed upriver to Bermuda Hundred and City Point. It still holds the world record as the longest temporary military bridge in modern history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments