By Sam McGowan

In the popular history of World War II, the assertion that the United States was caught unprepared in Hawaii and the Philippines has become widely accepted as fact. However, in the case of the Philippines, the proper word should be “under-prepared,” as this term more accurately represents the true situation that existed in the Philippine Islands in the early morning hours of December 8, 1941.

While neither the War Department nor the U.S. Navy expected the Japanese to attack the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, for several months before the day that President Franklin Roosevelt prophesied would “live in infamy,” authorities in Washington, D.C., had been planning for war to break out in the Pacific. When it did, they fully expected that the Philippines would be involved and preparations were being made to defend the islands. Unfortunately, the Japanese attack came before the preparations had begun in earnest. The allegation has also often been made that General Douglas MacArthur facilitated the destruction of the Army Air Corps in the Philippines through indecision. This is also more myth than fact.

In 1941, the Philippine Islands were a possession of the United States and had been for four decades. The islands had come into U.S. hands as a condition of the treaty with Spain that ended the Spanish-American War in 1898. Since that time there had been mixed emotions on the part of the Filipino people. While many had come to love the United States, which was a benevolent master in comparison to Spain, they also yearned for independence. Located just off the Asian mainland and stretching from the northernmost island of Luzon to Mindanao, the islands were the United States’ westernmost possession in the Pacific. The Japanese-owned island of Formosa lay some 450 miles to the north of Manila, the Philippine capital, while portions of mainland China that had been occupied by the Japanese were only a few hundred miles further, but to the west. The oil-rich East Indies lay to the south.

During the years between the world wars, the United States developed a series of contingency plans in the event of war with one or more foreign powers. These contingency plans were known as the Rainbow series. Planning for a potential war in the Pacific was found in the Rainbow No. 5 war plan, which basically called for the United States to fight a defensive war against Japan while concentrating the main effort on an offensive in Europe.

Under the provisions of Rainbow No. 5, the Philippines would be written off and abandoned to the enemy, while all U.S. forces would withdraw to a defensive line running from Alaska through Hawaii. Rainbow No. 5 was approved in the spring of 1941, but the plan was revised as the threat of war intensified. Because of their proximity to Japanese territory in the Pacific, the War Department decided that the Philippines was revised to one of strategic importance in the defense of the region.

Prior to 1941, the War Department paid little attention to the Philippines except for maintaining the garrison forces at Fort Stotsenberg and cavalry and infantry troops made up of Filipinos led by American officers. The Navy maintained facilities at Cavite on Manila Bay, where a few destroyers and PT boats were based, along with a seaplane squadron equipped with Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats. As late as the spring of 1940, Army Air Corps assets in the islands consisted of a few obsolete open-cockpit, fixed landing gear Boeing P-26 pursuit planes, a handful of B-10 bombers, and three more modern Douglas B-18s.

Things began to change in the Philippines in the late summer of 1941 as American relations with Japan deteriorated. When Japanese forces occupied French Indochina, President Franklin Roosevelt responded with an embargo on the sale of oil and other products to Japan in keeping with previous economic sanctions against the country. The move precipitated worsening relations, and it soon became apparent that war in the Pacific was inevitable—and that the Philippines would be in the line of the Japanese advance southward toward the oil fields in the Netherlands East Indies.

The United States began to build up its Philippine-based forces, and former U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur, who had retired in the Philippines where he served as field marshal of the Filipino military, was recalled to active duty to take command of all military forces based there. Several U.S. Army air and ground units were alerted for movement to the Philippines.

The buildup of air strength in the islands was crucial to the new American plan. New Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter planes were sent to replace the outmoded P-26s, along with two squadrons of Seversky P-35s. While the P-35s were of a more recent design than the open-cockpit P-26s, they were already obsolete by 1941 standards. Additional B-18s were sent to replace the antiquated B-10s in the 28th Bombardment Squadron. By August 1941, Air Corps strength in the Philippines consisted of one squadron of P-40s, two squadrons of P-35s, and two squadrons of B-18s. One Filipino squadron was still equipped with P-26s. The B-10s had also been transferred to the Philippine Air Force.

More modern aircraft were on the way; the newly created Army Air Forces Headquarters believed that the presence of a large force of heavy bombers would serve to secure the islands and perhaps deter Japanese threats to the region. The theory would soon be proved unfounded, but in 1941 four-engine Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and the newly developed Consolidated B-24 Liberators that had been designed as their replacements were believed to be capable of destroying powerful naval forces while the ships were still at sea.

Additional fighter planes were authorized for delivery direct from the factories to the Philippines, with others to be taken from operational units in the United States. War Department plans for the Philippines called for four heavy bomber groups with 272 operational airplanes and an additional 68 in reserve along with two pursuit (fighter) groups of 130 airplanes to be in place by April 1942.

In May, elements formerly with the 19th Bombardment Group arrived at Hickam Field, Hawaii, for duty with the Hawaiian Air Force. At that time, they were the only U.S. heavy bombers stationed outside the United States. In late July, the Army Air Corps relocated the entire group to the Philippines, with a provisional squadron from the Hawaiian Air Force making the initial move. On the morning of September 5, 1941, nine Flying Fortresses with 75 air and ground crew members aboard left Hickam for Midway Island on the first leg of a journey that would take more than a week to complete.

From Midway, Major Emmett “Rose” O’Donnell led the flight of B-17s on to Wake Island, then south to Port Moresby on Papua, New Guinea. This leg of the flight brought the bombers over territory that belonged to Japan by mandate. The flight departed Wake at midnight so the bombers would be over Japanese territory during the hours of darkness to avoid detection. Their final stop before proceeding northward to their destination at Clark Field in Central Luzon was Darwin, a town on the north coast of Australia.

The arrival of the B-17s reassured the senior officers in the War Department in Washington that the Philippines could, in fact, be reinforced by air if need be. Impressed by the flight, General MacArthur authorized the establishment of refueling sites in New Guinea and Australia in preparation for future movements.

Plans were made for the transfer of additional Army Air Forces groups to the islands. In November, the Rainbow No. 5 plan was revised somewhat in that military strength in the Philippines was to be increased substantially, including a major buildup of air power. By the end of the month, the U.S. Army in the Philippines was to receive an additional 26 B-17s to fill out the complement of the 19th Bombardment Group. In addition, the 27th Bombardment Group (Light) was to arrive aboard ship, with its complement of 52 Douglas A-24 dive-bombers to follow.

Although the United States military was strapped for personnel and equipment, the defense of the Philippines was given the highest priority. The War Department scraped the bottom of the barrel to find units to deploy, while additional air assets and ground troops were being trained for movement to the islands. Since the Wake Island-to-Moresby route came in close proximity to Japanese territory, a new South Pacific ferry route was considered. Plans were also made for a route over which fighters could be delivered to the Philippines from assembly points in Australia.

After the initial deployment of the 14th Bombardment Squadron, the entire 19th Bombardment Group was alerted in mid-October for movement to the islands. The group’s remaining 26 Flying Fortresses departed Hamilton Field, Calif. and had arrived at Hickam by October 22. By November 6, barely a month before the outbreak of the war, 25 B-17s had arrived at Clark. One airplane was temporarily grounded at Darwin but arrived within a few days.

Only two squadrons of the 19th Bombardment Group made the trip to the Philippines. The 28th Bombardment Group, which had been in the Philippines for more than a decade, joined the unit along with the 14th Bombardment Squadron, which had arrived from Hawaii in September. Personnel from the 28th gave up their twin-engine B-18s and joined the 19th to fly B-17s. The B-18s were reassigned to liaison duty.

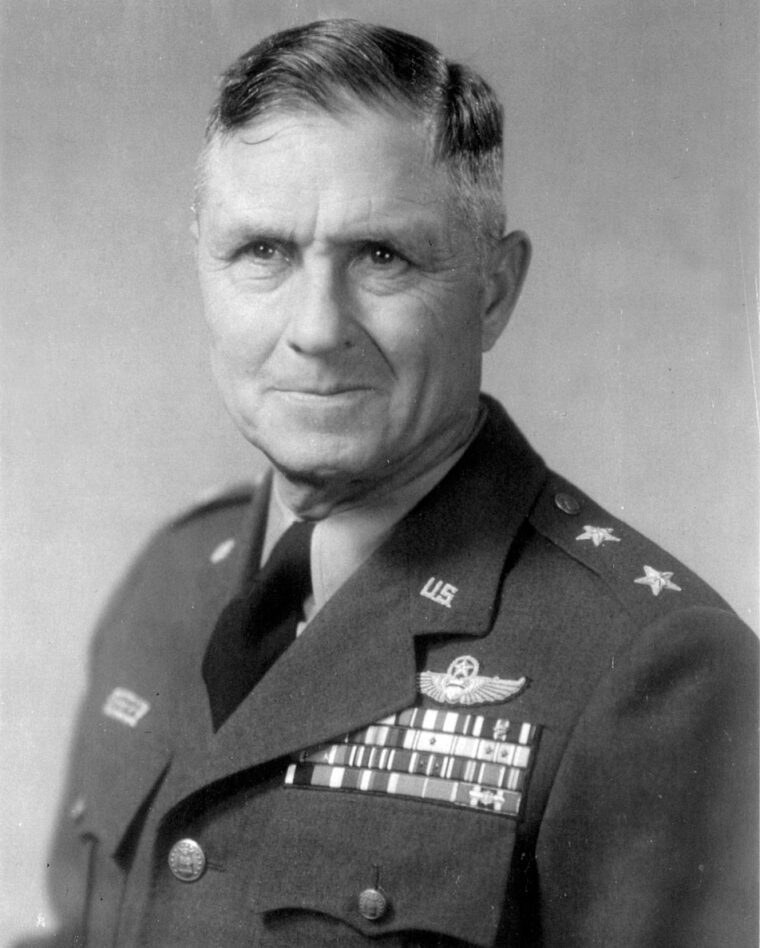

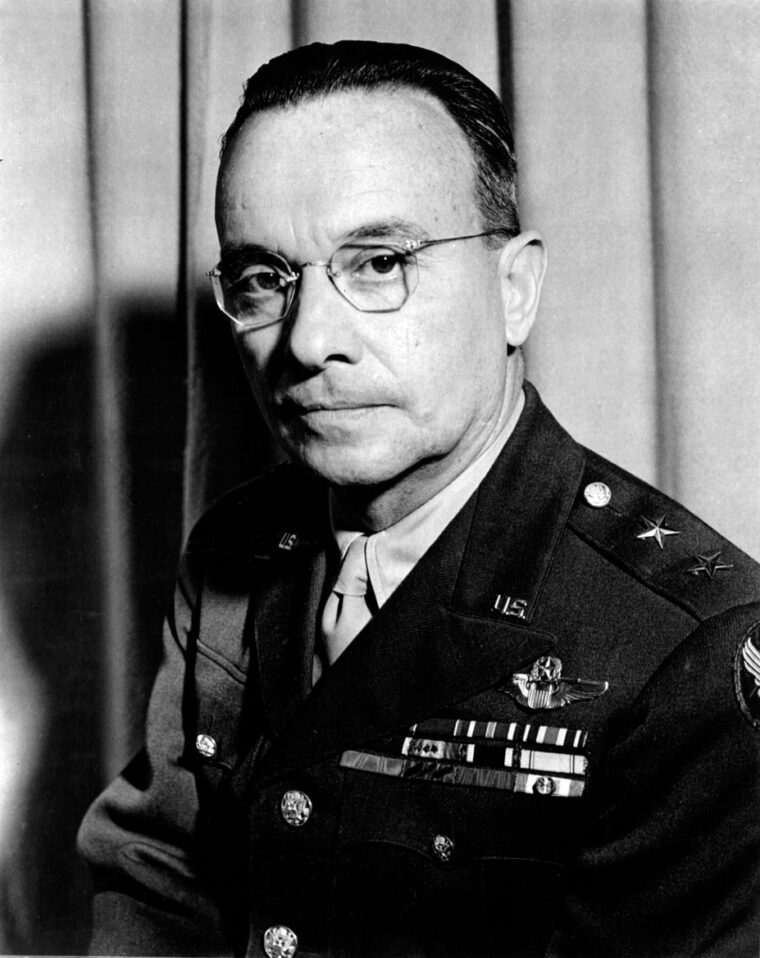

With the arrival of the additional B-17s, U.S. heavy bomber strength in the islands was up to 35 airplanes and more were scheduled to make the trip. Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton was sent to Manila to take command of all air units in the islands and assume a place on General MacArthur’s staff. On November 16, the Far East Air Force (FEAF) was activated under Brereton’s command. Authorization had been given for the establishment of the Fifth Air Force, but the headquarters had not been activated before the war broke out, although the bomber and pursuit commands were. The new FEAF included V Bomber Command under Lt. Col. Eugene L. Eubank and V Interceptor Command under Brig. Gen. Henry B. Claggett.

In early November, an order was put out that all “modernized” B-17s would be sent to the Philippines. Additional heavy bomber squadrons, including some that were set to be equipped with the new B-24 Liberator, were also ordered to the islands. The 7th Bombardment Group was on its way to Clark Field, with the ground components setting sail from San Francisco on November 21. The first flight of B-17s was scheduled to depart California in late November and early December. Additional B-17s and B-24s would follow as they were delivered from the factories.

While the arrival of the heavy bombers would give the American forces in the Philippines the power to strike at Japanese positions on Formosa and in parts of China, the increase in pursuit capabilities would provide protection from air attack. In early October, the Air Corps activated the 24th Pursuit Group in the Philippines. A month later it was joined by elements of the 35th Pursuit Group, although that group’s headquarters was still at sea when the Japanese attack came. By the end of November, all of the pursuit squadrons had been equipped with either P-40Bs or Es, except for the 34th Pursuit Squadron, which was still flying P-35s.

To protect Luzon, the fighter squadrons were dispersed with the 17th and 21st squadrons operating out of Nichols Field outside Manila and the 20th at Clark Field. The 3rd Pursuit Squadron was based at Iba, a small grass field on the China Sea across the 2,000-foot Zambales Mountains from Fort Stotsenberg and Clark. Iba Field was barely large enough to accommodate the 18 Curtis P-40Es that made up the 3rd Pursuit Squadron, but it was the closest fighter airfield to the approach routes to the American military installations around Manila. Previously, Iba had been used primarily as an advanced field for gunnery training on the ranges in the nearby Zambales.

Along with the basing of the 3rd Pursuit Squadron at Iba, General Brereton stationed an aircraft early warning radar team there, although the technology was still new and the operators were just learning their trade. Because of its location, Iba was a logical choice for a radar site. In all, seven radar sets had arrived in the Philippines by early December, but Iba was the only one operational. Another at Manila was in the process of being set up when war came.

General MacArthur borrowed from the Chinese practice of establishing a rudimentary aircraft warning system that depended on Filipinos stationed at crucial locations and connected to V Fighter Command by telephone and telegraph. Information received from the sites would then be transmitted to a plotting center at Clark Field. It was a burdensome system made even more so by the primitive Filipino communications. During early tests, it took nearly an hour for word of spotted aircraft to reach the interceptor command post at Nichols Field.

Iba was not the only airfield that the Far East Air Forces elected to develop in its plan for the defense of the Philippines. Members of Brereton’s staff felt that a heavy bomber base in the Southern Philippines on Mindanao was needed, a proposal that was initially opposed since the Rainbow No. 5 plan did not call for ground forces to be used to defend that particular island. But the soil on Mindanao was ideally suited for all-weather runways, a factor that weighted the argument in favor of a southern base.

Until a new airfield could be constructed, a temporary base was set up at the airstrip on the island’s Del Monte pineapple plantation. On December 5, two squadrons from the 19th Bombardment Group, half the heavy bomber strength then in the islands, deployed to Del Monte Field. Brereton’s operations plan called for the bombers to be based on Mindanao but to stage through Clark on missions against Japanese positions on Formosa if war came. The Fifth Air Base Group arrived at Manila aboard the transport ship USS Coolidge in early December and was sent immediately to Mindanao by island steamer to support the B-17s.

The United States initially based its build-up in the Philippines on a timeline that would see war with Japan beginning sometime in the spring of 1942. However, a worsening diplomatic situation was leading to an increase in the potential for hostilities—to the point that by November it was apparent that war could break out at any moment. In early November, the War Department sent a message to commanders in the Pacific advising that war with Japan was imminent but that it was extremely important for the Japanese to carry out the first hostile act.

Apparently, the leadership in Washington believed the American public would be more likely to support a war if the Japanese attacked first. General MacArthur apparently interpreted this letter to include any action that could be considered hostile and forbade reconnaissance missions over Formosa even when unidentified aircraft were reported around and over Luzon. In late November, in response to a British suggestion, the War Department notified General MacArthur that two long-range B-24 Liberators equipped with photographic equipment would depart for the Philippines by November 28. Their mission would be to photograph Japanese installations in the Marshall Islands and the Carolines.

As it turned out, the departure of the modified Liberators was delayed and the first arrived in Hawaii on December 5. It was held at Hickam Field for armament modifications and would become the first American aircraft loss of the war when Japanese planes struck Hickam on December 7.

The Air Corps intensified its preparations for war in early November, and General Brereton ordered all of his commanders to be prepared for any emergency. Aircraft were to be dispersed and kept on an operationally ready status, with their crews on two-hour alert day and night. The 19th Bombardment Group was ordered to maintain one squadron for reconnaissance and bombing missions at all times, while the 24th Pursuit Group was to have three planes from each squadron on alert from dawn until dusk. The orders were put into effect on November 10, nearly a month before war broke out. Within less than a week, all pursuit aircraft in the islands were placed on constant alert, with the airplanes fully armed and the pilots on a 30-minute alert. Some fighter pilots slept by their airplanes.

Early December saw an increase in the effort to beef up American air strength in the Philippines. While only 35 heavy bombers had arrived in the islands, others were on the way, along with 52 A-24 dive-bombers for the 27th Bombardment Group and 18 additional P-40s that were bound for the islands aboard ship. On December 1, Army Air Corps commanding general Henry H. Arnold notified the commander of the Hawaiian Air Force, “We must get every available B-17 to the Philippines as soon as possible.”

On December 6, a flight of 13 B-17s left Hamilton Field for Hickam on the first leg of their journey to Clark. Their arrival at Clark would have continued the buildup of the heavy bomber force that was expected to be at full strength by April 1942. Unfortunately, time was running out at a rate much faster than expected.

Even though new aircraft were arriving in the Philippines on a regular basis, that did not mean they or the men who flew them were operationally ready. The fighters arrived in crates and required assembly and maintenance before they were combat ready. Engines had to be broken in and slow-timed, while guns had to be bore sighted. Many of the fighters were still not operationally ready when war broke out. A major problem for the fighter pilots was the lack of a source of oxygen in the islands, which restricted the P-40s to sustained operations at altitudes of 15,000 feet and below.

The pilots themselves were inexperienced, which was a factor in what happened when war came. Most were fresh from pilot training and had very little experience in the P-40s they were to take into combat. More fighters would be lost in the battle for the Philippines to accident and mechanical failure or simply running out of fuel than to combat. Their radio equipment was primitive, and everyone in the islands used the same frequencies. Even though the P-40s were first-line fighters, one squadron, the 34th Pursuit, was still equipped with obsolete P-35s.

During the more than 60 years since December 7, 1941, many historians have concentrated on the “lack of decisiveness” on the part of General MacArthur during the first hours of the war. They have given the impression that no action was taken by the air forces in the Philippines, that the Japanese caught the air force on the ground and destroyed it within minutes. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth.

The American forces in the Philippines learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor within an hour after it started, not through timely notification by the War Department, but through a local radio station that picked up a broadcast from a Honolulu station and contacted the military. The Navy already knew of the attack but had failed to inform MacArthur’s headquarters in Manila. Upon receiving the news, MacArthur immediately informed his subordinates that the country was at war and instructed them to take appropriate action.

The Army Air Forces squadrons were informed. They were already on a status of high alert and had been for several weeks. On the evening of December 7, the officers of the newly arrived 27th Bombardment Group, which still had no airplanes, threw a party for General Brereton at the Manila Hotel. Brereton was called out of the party for conferences with Admiral W.R. Purnell, the senior naval officer in the islands, and General Richard Sutherland, chief of staff for MacArthur, who informed him of a message from Washington advising that war could break out at any moment.

Brereton notified his air units and canceled a training operation for the B-17s that was scheduled for the next day. Within an hour after the party broke up at 2 am (December 8, Philippine time) word reached the Philippines that Hawaii was under attack.

Within 30 minutes after the first word of the attack reached Manila, the Army Air Forces radar site at Iba picked up a large formation of unidentified airplanes about 75 miles offshore and plotted their track toward the island of Corregidor. The 3rd Pursuit Squadron dispatched its fighters to make the intercept, and they were tracked by radar as they flew toward the unknown formation. The radar operators saw the blips merge on their scope, but the fighter pilots never saw the unknown aircraft in the predawn darkness. Apparently, they had flown beneath the Japanese. After failing to locate the unidentified aircraft, they returned to Iba and breakfast. What the Japanese did is unclear, since the first attacks were still several hours away. Apparently, they were on a reconnaissance flight.

The U.S. forces in the Philippines were officially notified at 5 am Manila time that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. At this point the record becomes confused. Air Force historians Wesley Craven and James Cate point out that no real record exists of the events of December 8, 1941, as they took place in the Philippines. What records were kept were lost during the coming events in the islands, while unit histories were written after the fact and were possibly—even probably—considerably contrived.

At the request of General Arnold, author and historian Walter D. Edmonds eventually took over a project, which had begun in 1942, involving interviewing participants in the battles for the Philippines and Java. Edmonds interviewed dozens of airmen and carefully scrutinized diaries and combat reports. He published the results in the book They Fought With What They Had, which was originally published in 1951.

Edmonds believes that the official records were compiled after the fact and were sometimes doctored so they agreed with the positions of certain senior officers. General Brereton published his Brereton Dairies right after the war, and General MacArthur promptly denied some of the information contained therein. General Arnold claimed that he never really knew what happened in the Philippines on December 8 even though it was widely known that a detailed report was sent to him within days of the event.

Many historians focus on the Japanese 11th Air Fleet being grounded at its airfields around Tainan on Formosa due to a thick fog. While the Japanese naval aircraft did not launch until the fog lifted, army bombers were not hampered by the weather. A formation of twin-engine bombers attacked Baguio at around 9:30. Accounts differ as to when Iba was attacked. Although most historians record that the field was attacked simultaneously with Clark, other reports indicate that Iba was first struck at daybreak, shortly after the 3rd Pursuit Squadron returned from its attempted interception of the Japanese formation just before dawn. Based on reports from those interviewed by Edmonds, the Iba attack came shortly before the attack on Clark.

At 5 am General Brereton was at General MacArthur’s headquarters at Manila. The Air Corps commander wished to gain permission from MacArthur for a strike on the Japanese airfields on Formosa, or so he said in his memoir. According to legend, General Richard K. Sutherland, MacArthur’s chief of staff, kept Brereton from meeting with his boss. MacArthur claimed that he was never consulted about an attack and that he would not have approved it anyway, as it would have been futile. Whether MacArthur’s observation was based on the reality of the time or came through the gift of hindsight, it was pretty astute.

Regardless of what really happened, at 10:14 Brereton reported that he received a phone call from MacArthur authorizing him to carry out an attack on Formosa in late afternoon at his discretion. A few minutes before the phone call, Lt. Col. Eugene Eubank, the commander of V Bomber Command, left for Clark with orders to dispatch a reconnaissance flight over the Japanese airfields on Formosa in preparation for a strike. There is reason to believe that Brereton received authority, possibly from Sutherland, to mount an air strike against Japanese installations on Formosa as early as 8 am.

Instead of taking no action, as so many have asserted, the Army Air Forces in the Philippines were very active from the moment they were notified of the attack on Pearl Harbor and Hickam, and even earlier in the case of the squadron at Iba. Fighter patrols were in the air within an hour of the notification that war had come. Around 8 am, at the insistence of Colonel Harold George, the chief of staff of V Fighter Command, all of the B-17s at Clark were ordered to take off so they would not be caught on the ground by an expected Japanese attack. The detachment at Mindanao was notified to prepare to return to Clark for a bombing mission.

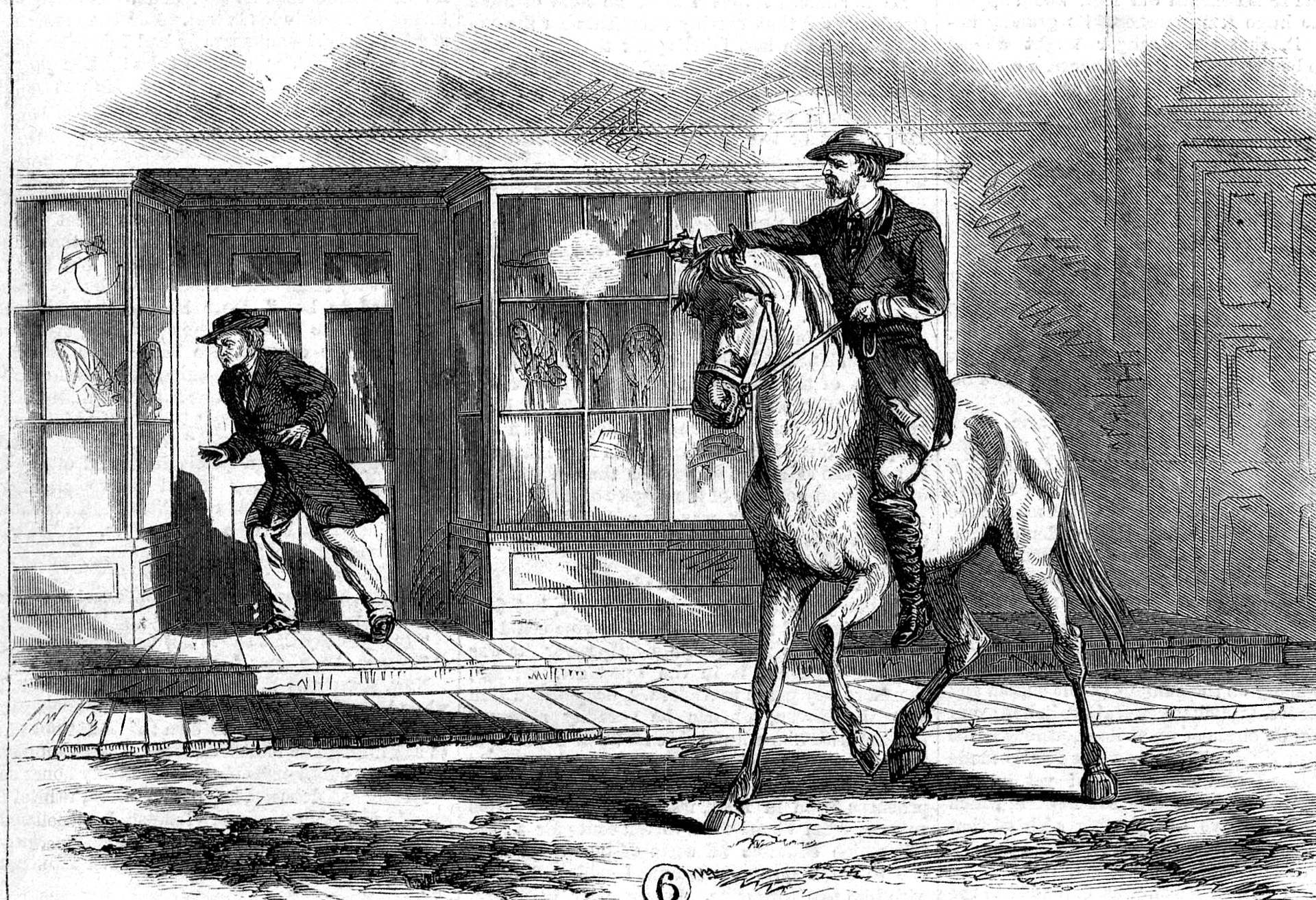

At 9:23, Colonel George reported that two formations of multiengine bombers were over northern Luzon. The 20th Pursuit Squadron was directed to make the interception, but the Japanese turned east and struck the Filipino summer capital of Baguio instead of continuing south toward Clark Field or Manila as expected. Other Filipino cities were reportedly bombed during the morning hours, including Tarlac, a town just north of Clark Field, and Tugegararo, a city in northern Luzon. American P-40s from the 20th Pursuit Squadron had expected to intercept the Japanese fighters over Rosales, a town south of Baguio, but failed to make contact with the enemy.

By all indications, Iba was the first Air Corps field to be attacked. Some have written that the tiny airstrip was attacked shortly after dawn as the P-40s from the 3rd Pursuit Squadron were returning from their predawn attempted interception over the China Sea. Such, however, apparently was not the case. Nor were all of the 3rd airplanes destroyed on the ground. In fact, only one was on the ground when the Japanese bombers appeared overhead. The rest were still airborne. Edmonds reports that the telephone line between Iba and Clark went dead at 11 am, leaving radio contact as the base’s only means of communicating with other units. Thirty minutes later, the Iba radar picked up a large formation about 100 miles out to sea. The 3rd Squadron commander, Lieutenant H.G. Thorne, ordered his pilots to start their engines, but to remain on the ground since the Japanese seemed to be milling around over the ocean.

Shortly after the 3rd Pursuit pilots manned their aircraft, they received an order from Interceptor Command headquarters to take off and climb to 15,000 feet and to remain over Iba. All 18 airplanes took off, in three flights of six airplanes each, but they never assembled as a squadron, apparently due to the difficult communications from the radio clutter on the fighter frequency. At the time, there were fighters in the air all over Luzon, and all were trying to obtain instructions.

One flight from Iba headed for Manila in hopes of receiving explicit instructions. After circling over Nichols Field for a while and receiving no orders, the flight commander led them back toward Iba as their fuel supply began to dwindle. They arrived over Iba to discover the field under attack. The P-40s dove into the Japanese and broke up a strafing attack before it got started, but their fuel was low and they had to get on the ground. Four were shot down while trying to land at Iba; one pilot crash-landed in the sea just off the airfield, and one flight went to Clark and joined the combat there. Several 3rd Squadron airplanes found safety at Rosales, a strip near Lingayen Gulf.

Even though the P-40s broke up the Japanese strafing attack, the level bombers hit the field with pinpoint accuracy, destroying the radar site, killing the operators, and hitting the few buildings on the field. Casualties were reported as 50 percent either wounded or killed, and the airfield was rendered useless. The flight surgeon, Lieutenant Frank Richardson, rounded up as many trucks as he could find and loaded them with wounded. He then set out down the coast for Manila.

Lieutenant F.C. Roberts, the pilot who crash- landed on the beach, organized the uninjured survivors and led them on a march through the mountains toward Clark. Failing to find a cart track leading toward Fort Stotsenberg, many of the men got lost and wandered in the jungle-covered mountains for several days.

After receiving approval to launch an attack on Formosa, Brereton recalled the bombers to Clark to refuel and rearm. He ordered Eubank to have the B-17s armed with 100- and 300-pound bombs and to have the crews briefed for an attack on Japanese airfields in southern Formosa late that evening. He also sent word to Del Monte ordering the two squadrons of B-17s that were there on deployment back to Luzon in preparation for an attack the next morning, but to use an emergency strip at San Marcelino rather than Clark itself. They were to be prepared to fly a mission at daybreak the following morning. Two B-17s were dispatched on reconnaissance missions over Formosa. It was not until 11:30 that the last bomber landed.

Although it is commonly believed that the attack on Clark came without warning, in fact the radar report from Iba of a large formation over the China Sea had been sent to Fighter Command. The target was believed to be Manila, and the 17th Pursuit Squadron was ordered into the air to patrol over Manila Bay. The 34th Pursuit was supposed to take off and cover Clark but failed to get the word. When Japanese planes appeared over Clark, the 21st Pursuit took off to intercept them but was diverted to patrol over Cavite. The 20th Pursuit was on the ground at Clark refueling after its fruitless mission over northern Luzon in the morning. The 19th Bombardment Group B-17s were in the process of refueling and rearming. Some of the crews had gone to the mess tent for the noon meal.

The first attack on Clark came from a 54-plane formation of level bombers, which flew over at 18,000 feet. The bombs impacted across the field diagonally, and most of the buildings were hit. The flight line where the B-17s were parked received very little damage from the attack, but most of the P-40s were hit. When the bombs began falling, Lieutenant Joseph H. Moore led a four-plane formation of P-40s off the ground. Ten others were behind them preparing to take off. They were caught in the bomb pattern, and most were destroyed without getting off the ground.

At this point, the B-17s were still largely undamaged, but the bombing was followed several minutes later by a vicious strafing attack by Japanese fighters that came right down on the deck, pouring cannon fire into the parked bombers. The Japanese were not unopposed. The first flight of Zeros was intercepted by Joe Moore and his three wingmen. Lieutenant Randall D. Keator promptly shot down a Zero and was awarded the Silver Star for the first recorded American victory of the Southwest Pacific War. Moore got two more.

The P-35s of the 34th Pursuit took off from Del Carmen for Clark and were promptly intercepted by Japanese fighters. Although the victories could not be confirmed, 34th pilots claimed to have shot down three of the Japanese fighters. Another interception was made by the six P-40s of C Flight from the 3rd Pursuit which had rushed to Clark after receiving word that it was under attack. Unfortunately, all six airplanes were low on fuel and one pilot bailed out when his engine quit. He was strafed by Zeros while he hung in his parachute. One P-40 flew into the side of Mt. Ararat, a huge volcano just east of Clark Field. Lieutenant Herbert Ellis had to bail out of his burning airplane, but not before he shot down three Japanese fighters.

Unfortunately, the effort of the American P-35 and P-40 pilots was too little and perhaps too late. The devastation to the Air Corps at Clark was overwhelming. All of the B-17s on the ground were severely damaged in the strafing attack, but three would be repaired. Damage to the fighter force was equally great, although many of the fighters were lost to causes other than enemy action. Several ran out of fuel and others crash-landed due to engine trouble because they had not been properly broken in. Nearly every airplane on the ground at Clark was destroyed, with the most serious losses being the B-17s and the 10 P-40s that were caught in the bomb pattern before they could get off the ground.

The disaster at Clark was not caused so much by a lack of preparedness on the part of the military as by a combination of factors that stacked up against the U.S. forces. Had the B-17s remained aloft or been sent south to Mindanao until the Allied force could get organized, they would have been spared. Had the fighters from Nichols Field continued to Clark, they might have broken up the strafing attack as the 3rd Pursuit P-40s did at Iba. The loss of the 10 P-40s from the 20th Pursuit was more a matter of timing than anything else. The airplanes were refueled, armed, and ready to go, but they started taking to the air a few minutes too late.

Regardless of the reasons , the Air Corps at Clark had suffered grievously. The remaining pilots would fight gloriously over the next few weeks and months, but the ultimate fate of the Philippines had been determined long before the first bombs fell at Clark Field. n

Sam McGowan is the author of The Cave, a novel of the Vietnam War. He has also written extensively on the subject of air power during World War II.

This article reads like another attempt to salvage MacArthur’s reputation, cherry-picking an issue to redirect attention from his massive failures in the defense of the Philippines.

MacArthur was told of the Pearl Harbor attack at 3am; at 4am Gen. George Marshall cabled him to follow thru with the established war plans. At 5am Gen. Brereton of the USAAF began several attempts to get MacArthur’s approval for offensive operations. This was finally given over 5 hours later. To judge whether or not an attack could have succeeded is indeed Monday morning quarterbacking. In fact, the Japanese on Formosa fully expected to see our B-17s coming, and Mac knew our war plans called on him to use all his weapons to confront the enemy.

His dithering for over five precious hours led to the timing and results this article describes. Instead of being court marshalled for trying to obey two masters, (he was also employed by the Philippine government as a military trainer and supervisor) he was later awarded a medal for his “spirited” defense of the Philippines.

The original plan also called for a steady retreat to Mindanao. Although that would have also been problematic, the nature of the island as a wild and unfriendly place, especially for the Japanese, would have made possible some sort of prolonged defense. In general, it can be truthfully said that though the winds of war were apparent to the allies in all the theatres, little real effort was made for vigorous defense until too late. Churchill, de Gaulle, Billy Mitchell and a few others were right but were heeded far too late.