By Michael D. Hull

Recently put ashore, three companies of U.S. Marines advanced stealthily along the Matanikau River on the northern coast of Guadalcanal on September 27, 1942.

Running into unexpectedly heavy Japanese opposition, the leathernecks were trapped on the beach, and it became necessary for them to be evacuated. The seaplane tender USS Ballard was sighted offshore, and a Marine sergeant arm-signaled the desperate situation. The ship hastily mustered its flotilla of five Higgins boats to extract the Marines.

Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro of the U.S. Coast Guard volunteered to undertake the rescue mission. Under a hail of enemy machine-gun fire, he led the boats to the shore and hurriedly loaded them with wounded Marines. The Japanese fire increased, and Munro placed his boat in a position to shield the evacuation. Able-bodied leathernecks fought off the Japanese as more Marines were loaded in the boats.

As the laden boats began to pull away, Munro noticed that one of the craft had run aground on jagged coral. He maneuvered alongside and pulled it free. When an enemy machine gun on the beach opened up, Munro and crewman Raymond Evans fired back with their two bow guns and silenced the Japanese. But enemy rounds had mortally wounded Munro. He remained conscious long enough to ask weakly, “Did they get off?” Evans replied, “Yes.” Munro smiled and then died. The 22-year-old Munro and his boat crews saved an estimated 500 Marines that day.

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, and raised in the little town of Cle Elum, Washington, Munro had enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1939 and spent 18 months aboard the cutter Spencer in the Atlantic before transferring to the West Coast. He served aboard the attack transport Hunter Liggett during the Guadalcanal landings before being assigned to the landing boat pool. His mother, Edith, accepted his posthumous Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 24, 1943, and then enlisted in the Coast Guard.

Munro was the only Coast Guardsman to recieve the nation’s highest decoration in World War II, but during the 200-year-old maritime service’s immense and far-flung role in 1941-45, his comrades were awarded many medals and commendations for valor. These included six Navy Crosses, two Distinguished Service Medals, 64 Silver Stars, 96 Legions of Merit, 12 Distinguished Flying Crosses, and many Air Medals, Lifesaving Medals, and Bronze Stars.

Though generally overlooked by most historians, the U.S. Coast Guard performed sterling service in almost every phase of the sea war and in all theaters of operations, starting even before America entered the hostilities. Besides guarding the coastlines, keeping ports secure, and training merchant mariners, its dedicated officers and seamen manned several types of vessels and aircraft, battled German U-boat packs, performed numerous rescue operations at sea, and took part in every major Allied amphibious invasion. Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, observed, “In wartime operations, Coast Guardsmen performed individual acts of heroism as valorous as those of any other of the armed services…I know of no instance wherein they did not acquit themselves in the highest traditions of their service, or prove themselves worthy of their service motto, ‘Semper Paratus’ (Always Ready).”

Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, thrust America into the war, Coast Guard personnel were on active duty in the frigid waters around Greenland and Iceland. Their cutters broke ice and kept convoy routes open for merchant ships, rescued survivors of submarine attacks, reported on weather and ice conditions, and maintained surface and air patrols. And a few Coast Guardsmen were the first Americans in action against Germans before their country was at war. They were members of the Greenland Patrol, which was established in the summer and autumn of 1941.

Early that September, a few days after the destroyer USS Greer exchanged fire with a U-boat, Commander Edward H. “Iceberg” Smith was in charge of a flotilla comprising the destroyer USS Bear and the Coast Guard cutters Northland and North Star. He learned that two groups of “hunters” with radio equipment had been dropped off by a Norwegian trawler north of McKenzie Bay on the east coast of Greenland. Smith placed a prize crew aboard the trawler, which was believed to be sending weather reports and information on Allied shipping to U-boats.

Commander Smith anchored the Northland in a fjord and dispatched a landing party to find a suspected German radio station. Twelve Coast Guardsmen led by Lieutenant Leroy McCluskey made their way through ice and darkness and came to a hunters’ shack. They surrounded it, kicked in the door, and rushed in to surprise three German radio operators resting in their bunks. The occupants surrendered and yielded their equipment and codes. Pretending to build a fire and make coffee for the Americans, the cunning Germans tried to burn some documents. But McCluskey’s men were too quick, and the papers were seized. The documents turned out to be Adolf Hitler’s plans for a network of radio stations in the far north.

By the late autumn of 1941, when the war situation in Europe and the Middle East had become critical, it seemed only a matter of time before America became fully involved. The Roosevelt administration was aiding the British and Russians, and American ships were helping to protect Atlantic convoys. But the Navy, facing a two-ocean war, desperately needed more vessels and personnel. So, on November 1, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8929, ordering the Coast Guard to operate as part of the Navy. It was to do so until January 1, 1946.

Under the guidance of its commandant, Admiral Russell Randolph Waesche, the Coast Guard underwent a rapid expansion of its personnel, vessels, bases, and equipment. A handsome man known for his foresight and resilience, Waesche was held in the “highest esteem” by Admiral Nimitz. Waesche, a Maryland-born graduate of Purdue University, had been a destroyer and cutter skipper and chased rum runners in the 1920s.

The Pearl Harbor attack accelerated Waesche’s buildup effort, with the Coast Guard increasing from 29,000 military and civilian personnel to a peak of 175,000 regulars and reservists in June 1944. An eventual total of 10,000 females served in Commander Dorothy C. Stratton’s newly-formed Women’s Reserves (SPARS), releasing male personnel for sea duty.

The Coast Guard entered the war with only 168 named vessels which were 100 feet or more in length. More craft were acquired, and by January 1, 1943, the service had a peak number of 802 vessels of 65 feet or more and 7,960 smaller craft. During the war, Coast Guardsmen served aboard a variety of Navy vessels, including destroyer escorts, frigates, attack transports, freighters, tankers, and infantry and tank landing craft.

Not only had some Coast Guardsmen seen action before their country went to war, but a few others were in the thick of the action on that fateful Sunday morning when Japanese carrier planes mauled ships of the Pacific Fleet anchored in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. At that time, the 327-foot cutter USCGS Taney, commanded by Captain G.B. Gelly was on routine patrol duty off Honolulu. Within four minutes of the initial attack, the cutter’s guns were fully manned and firing on scattered formations of Japanese planes.

When five enemy aircraft approached the Taney from over the harbor entrance on what appeared to be a glide bombing run toward the cutter or the Honolulu power plant, the cutter’s crewmen blasted the raiders with their three-inch guns and .50-cal. machine guns. There were no direct hits, but the planes were rocked by the salvos and swerved up and away. The Taney continued to patrol off Honolulu and later served as a headquarters ship in the great April 1945 invasion of Okinawa.

As the tempo of the war increased, an urgent demand grew for Coast Guardsmen both at sea and in shore duties, particularly port security and anti-sabotage patrols. One of their first major assignments was guarding the nation’s lengthy and vulnerable coastlines, particularly the Eastern Seaboard, off which long-range German U-boats prowled unmolested during the first half of 1942. Many Allied merchant ships were sunk within sight of East Coast cities, and there was the threat of Nazi spies and saboteurs landing from submarines. So, the Coast Guard’s “Beach Pounders” were formed. By boat, jeep, truck, on foot, and on horseback, Coast Guardsmen—working in pairs and often accompanied by sentry dogs—tirelessly patrolled the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts. Most areas were under constant surveillance by the end of 1943.

With the aid of the FBI and, on one occasion, an alert Boy Scout, Coast Guard vigilance resulted in the apprehension of German saboteurs at Amagansett, Long Island, Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, and near Machias on the Maine coast.

While Coast Guardsmen kept vigil along the shores, others were stalking the U-boats at sea. The Coastal Picket Patrol was organized by the Coast Guard in May 1942. Nicknamed the “Hooligan Navy,” it comprised auxiliary yachts and motor launches under 100 feet in length. Armed with small guns and depth charges, they were mostly commanded by their civilian owners and manned by yachtsmen unqualified for Navy service. The boats were deployed too late to repel the German submarines’ first blitz along the East Coast, but they patrolled faithfully during the hard winter of 1942-43.

The Hooligans were too small, slow, and feebly armed to score any kills. At top strength, in February 1943, there were 550 such craft cruising between Eastport, Maine, and Galveston, Texas. From that time, the numbers were progressively reduced as 83-foot Coast Guard cutters assumed their duties.

One of the most important activities of the Coast Guard during the war was security in the nation’s busy ports from New York to Galveston, Boston to Miami, and Seattle to San Juan. Working with the FBI and other federal and state agencies, Coast Guardsmen patrolled piers, inspected cargoes, screened longshoremen, fought fires, and successfully prevented sabotage and dangerous carelessness. The port security program, which absorbed 20 percent of the service’s personnel, was activated before America entered the war. During its existence, no injury or serious damage occurred to any facility or vessel for which the Coast Guard was responsible. Considering the many hazards from within and without, it was a remarkable achievement.

Coast Guardsmen also improved navigation on inland waterways, ferried landing craft to the coasts from industrial plants along the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes, and maintained coastal communications and navigation networks, including the new LORAN (long-range aid to navigation) system.

For service on the high seas, Coast Guard cutters and patrol boats traded their peacetime white paint for Navy gray or camouflage and were armed with guns, depth charges, and sonar detection equipment. Besides their own increasing fleet of craft, Coast Guardsmen manned 351 naval vessels ranging from troop transports to landing craft and 288 vessels of the Army Transport Corps.

In the Atlantic, Coast Guard cutters, frigates, destroyer escorts, and Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats and Grumman JF Ducks joined British, American, and Canadian naval units in protecting vital convoys of troops, weapons, and materiel to England for the Allied buildup. It was a bitter and costly struggle until the U-boat menace was minimized by May 1943, and a number of Coast Guard craft fell victim to Nazi torpedoes.

One of the earliest was the new 327-foot cutter Alexander Hamilton. While towing a disabled Navy supply ship in heavy seas 10 miles off Iceland on January 29, 1942, she was struck by a torpedo. The explosion killed her engine room crew, but the rest of her complement maintained perfect discipline. The cutter listed badly but stayed afloat, and crewmen were taken off by the destroyer USS Gwin and an Icelandic trawler. The Alexander Hamilton capsized while being towed into Reykjavik. Twenty-six Coast Guardsmen were killed in the action, and six died later of their wounds.

Destroying enemy submarines was the primary objective of the Coast Guard, and its vessels had played a vital role from the beginning. Two of the first three U-boats destroyed in American waters were sunk by the 165-foot cutters Icarus and Thetis.

On the afternoon of May 9, 1942, the USCGC Icarus was heading from New York to Key West, Florida, when she made sonar contact with a 500-ton U-boat on her maiden war cruise in shallow water off Cape Lookout, North Carolina. After an explosion erupted from a torpedo misfiring or detonating on the shoal bottom, Lieutenant Commander Maurice D. Jester decided to drop a spread of five depth charges. Three more were dropped, and the badly damaged U-352 was forced to surface. It grounded in 120 feet of water. Icarus crewmen swept the submarine’s deck with fire from their three-inch gun and machine guns, and the Germans abandoned ship in “clock-like precision.”

As the U-boat sank and 33 survivors bobbed in the water, Jester radioed to shore for help because he did not think his cutter could handle so many prisoners. He was ordered to pick them up anyway and take them to Charleston, South Carolina, for interrogation by Naval Intelligence. Meanwhile, on the afternoon of June 13, 1942, Lieutenant Nelson McCormick’s USCGC Thetis, based in Key West, dropped seven depth charges and sank U-157 north of Cuba in the Gulf of Mexico.

During the war, cutters and Coast Guard-manned Navy ships sank 11 enemy submarines, while a 12th was destroyed by a Coast Guard patrol bomber. Twenty-eight Coast Guard and Coast Guard-manned vessels were sunk, and 572 crewmen were killed in action. The service’s first combat death occurred on board the transport Leonard Wood when she was attacked by Japanese planes at Singapore on December 8, 1941. The Coast Guard’s wartime death toll was 1,030.

The versatile service excelled in shipboard and aerial search and rescue operations, and its personnel risked their lives in many waters, from Haiti to Algiers to Cherbourg. A total of 4,243 Allied military personnel and merchant seamen were saved by the Coast Guard in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. These included 1,658 survivors of enemy torpedo attacks along the Atlantic coast, in the Gulf of Mexico, and in the Caribbean. In addition, Coast Guard cutters rescued 810 survivors in the North Atlantic and 115 in the Mediterranean. Hundreds of others were saved by Coast Guard-manned Navy ships.

During Operation Torch, the massive three-pronged Allied invasion of North Africa on November 8, 1942, Coast Guard seamen earned high praise from Navy officers for their “courage, persistence, and intelligence” in handling troop transports and landing craft, sometimes under heavy fire. The Coast Guard personnel—many of them only briefly trained and lacking combat experience—underwent bombing, shelling, and strafing during the invasion, but lost none of their ships. They also downed three German bombers and rescued several hundred survivors from torpedoed vessels. For their heroic leadership, Commander Merlin O’Neill and Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Harwood of the Coast Guard-manned transports Leonard Wood and Joseph T. Dickman, respectively, were awarded the Legion of Merit, while Commander Roger C. Heimer of the Samuel Chase was commended by the British Admiralty for gallantry.

Coast Guard personnel manned cutters, attack transports, and landing craft during the U.S.-Canadian invasions of Attu and Kiska in the bleak, fog-shrouded Aleutian Islands in May-August 1943, and five seamen were awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for heroic rescues. With Allied forces on the offensive on several fronts, the year 1943 proved to be a challenging one for the men of the Coast Guard.

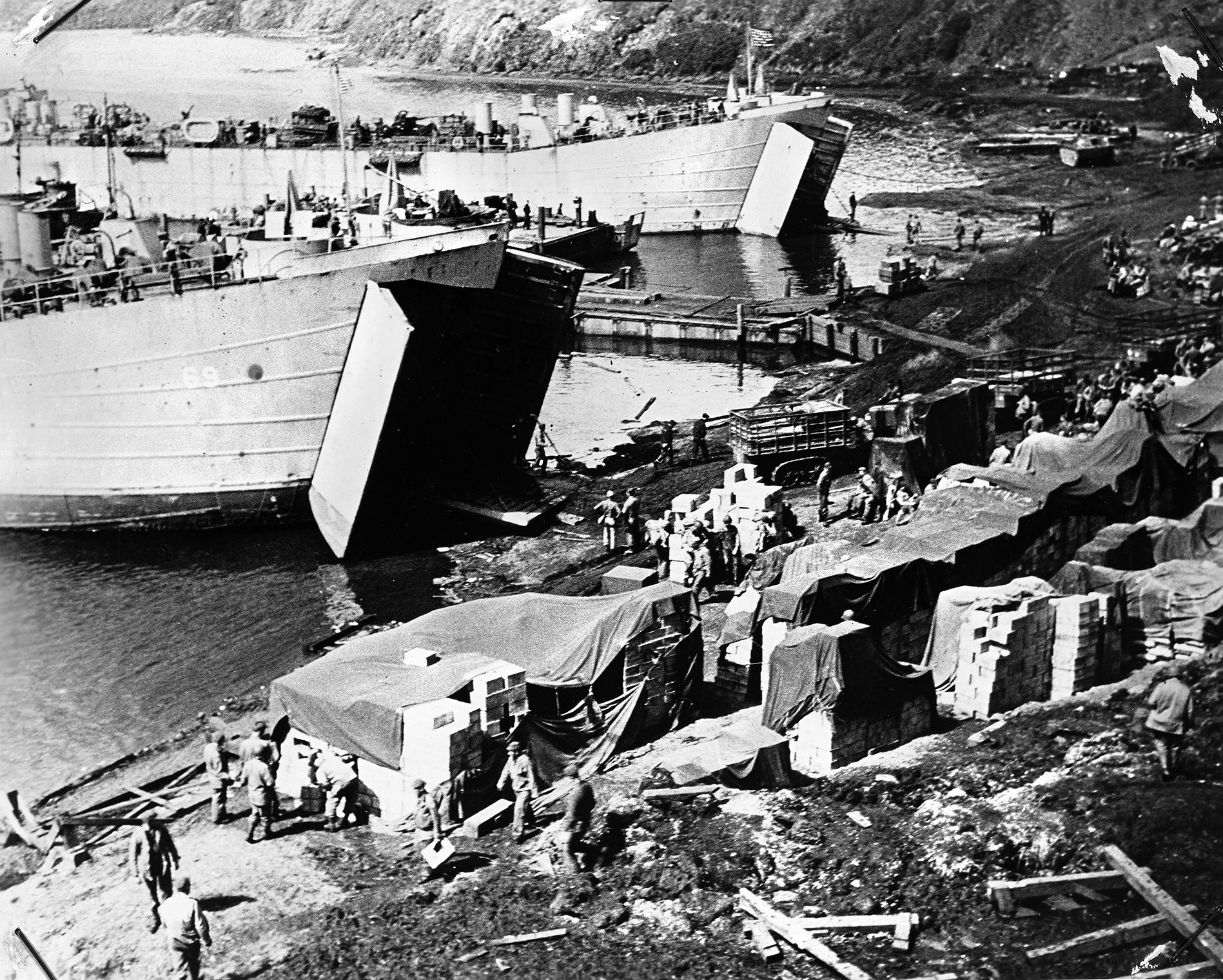

They manned many attack transports, landing craft of all types, and submarine chasers when the British Eighth and U.S. Seventh Armies invaded the eastern and western coasts of Sicily in Operation Husky on July 10. Hampered by winds, rough seas, and soft sand, the Coast Guardsmen braved enemy bombs, strafing, and machine-gun nests to land troops, vehicles, and ammunition. They also cleared mines and prepared the ports of Gela and Licata for handling more equipment and supplies, and again earned high praise from the Navy. Rear Admiral Harold Biesemeier said that the heroes of the western landings were the crews of the landing craft.

Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, the Navy’s premier historian of World War II, agreed, “If landing and beach craft crews had failed, the entire American part of Operation Husky would have failed, and the British would have been left to carry the war into Sicily unsupported. They did not fail; these young sailors performed marvels of valor and miracles of judgment. All honor, then, to these lads…since they proved themselves to be strong, brave, and resourceful.”

A few weeks after Sicily had been secured, Coast Guardsmen were again in action as Allied forces crossed the Strait of Messina and invaded mainland Italy. General Bernard L. Montgomery’s British Eighth Army seized a bridgehead in Calabria on September 3, and Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark’s Fifth Army and the British X Corps at the Gulf of Salerno on September 9. Once more, the Coast Guardsmen endured enemy bombing and shelling as they landed men, tanks, trucks, and supplies on the Salerno beaches. The German defenders counterattacked strongly, and Royal Navy cruisers and destroyers moved in close to shore in support. The entire bridgehead was threatened, and it was several days before the Fifth Army could break out.

After a few months’ respite while the Allied armies struggled northward up the Italian boot against stubborn German opposition, the Coast Guard units in the Mediterranean braced for their next invasion role. Operation Shingle was launched January 22, 1944, with the British 1st and U.S. 3rd Infantry Divisions landing at Anzio, behind the German lines on the western coast of Italy, in a bid to outflank the Gustav Line and the deadlocked fighting around Monte Cassino. The invasion initially achieved complete surprise, but Coast Guard-manned landing craft carrying infantry and tanks soon came under heavy fire from enemy artillery and machine guns. One landing craft grounded, another received near-misses, and there were many casualties, but 90 percent of the assault load made it ashore on D-day. However, the Germans rushed more men and weapons to the beachhead, and the Allied forces were hemmed in for four bitter months.

Several thousand miles to the east, more Coast Guardsmen saw much action as American and Australian ground and naval forces went on the offensive in the Pacific theater. After the long struggle to secure Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands, attack transports and landing craft manned by Coast Guard seamen played a crucial role in many invasions—at Bougainville, Cape Gloucester, New Guinea, the Gilbert Islands, Vella Lavella, the Russell Islands, the Treasuries, the Admiralties, Choiseul, Abemama, New Britain, New Georgia, Rendova, Eniwetok, Biak, Saidor, Hollandi, Wakde, Noemfoor, Emirau, Sarmi, Cape Sansapor, Angor, Morotai, Mindoro, Guam, Tinian, Saipan, Roi-Namur, Kwajalein, Peleliu, Aitape, Mariveles, Cebu, Negros, Subic, Lingayen, Balikpapan, Leyte, Samar, and Luzon.

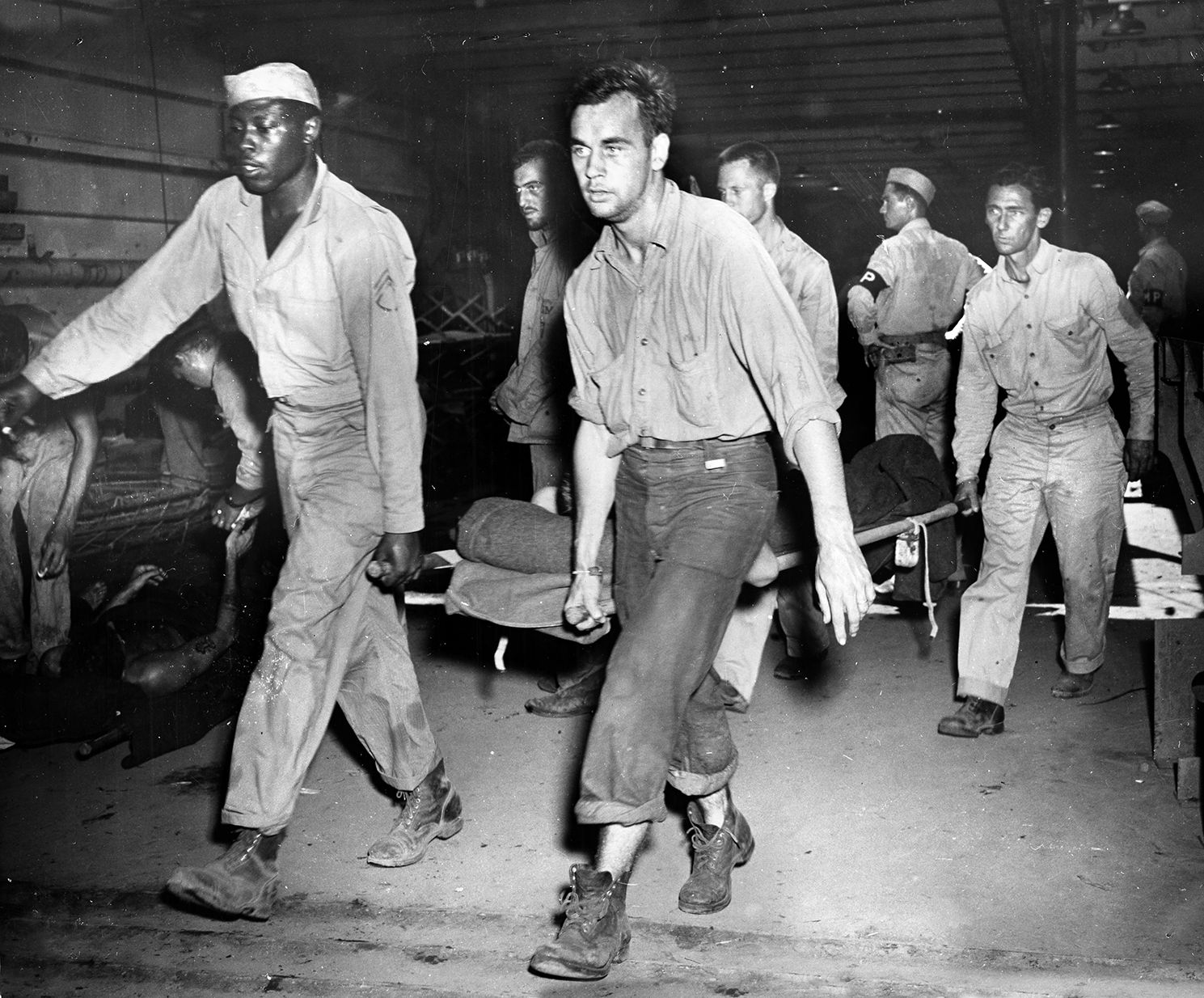

When Major General Julian C. Smith’s 2nd Marine Division made its costly assault on Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands on November 20, 1943, Coast Guard-manned attack transports and landing craft came under heavy fire. One of the transports, the Arthur Middleton, a veteran of the Aleutian campaign, served as a receiving ship for many casualties of the bloodiest Marine Corps action in the Pacific war.

The next big challenge for Coast Guardsmen in the Pacific came on February 19, 1945, when Major General Harry Schmidt’s Fifth Amphibious Corps invaded the volcanic, sulfurous island of Iwo Jima, 640 miles south of Tokyo. Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill’s attack force included 20 Coast Guard-manned transports and landing craft, while seven Navy ships had some Coast Guardsmen in their crews. The landing boats came under increasingly heavy mortar and artillery fire as they carried in the initial assault troops of the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions led by Major General Clifton B. Cates and Major General Keller E. Rockey, respectively. Many landing craft were hit and some broached, but the young Coast Guardsmen—many of them teenagers—kept going in through shell splashes time and again. As the Marines ashore inched their way forward against fierce Japanese resistance, the landing craft coxswains picked up casualties and took them out to the landing ships. The attack transport Bayfield became a makeshift hospital ship.

Then, less than two months later, came Operation Iceberg, the last major offensive of the Pacific war. After several days of naval and air bombardment, General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr.’s U.S. Tenth Army invaded Okinawa, midway between Formosa and Japan, on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945. An impressive array of Coast Guard-manned vessels, seven transports, two cutters, and 42 assorted landing craft, took part in the great invasion, ferrying in men of Major General Roy S. Geiger’s Third Amphibious Corps (the 3rd and 6th Marine Divisions) and Lieutenant General John R. Hodge’s XIV Corps (the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions). In addition, six Navy-manned transports had Coast Guardsmen in their crews. Again, the men of the Coast Guard displayed great heroism and fortitude under fire.

The landing craft came under attack by Japanese suicide planes in the early hours of the invasion, and three of them were casualties. When the Coast Guard-manned LST-884 commanded by Lieutenant Charles C. Pearson was struck by a Kamikaze, she burned brightly and her ammunition cargo exploded. The crew abandoned ship, and men in the water were picked up by other boats. After the heavier ammunition had exploded, Pearson, four other officers, and two seamen boldly returned to the LST, manned the pumps, and tried to douse the fire. Three other officers and 15 seamen voluntarily returned to assist, the fire was brought under control, and the craft was towed away for repair.

While the Marines and Army troops fought doggedly for more than two months to root out and destroy the enemy defenders on Okinawa, the Allied fleet was under constant attack by Kamikazes. The cutter USCGC Bibb was subjected to 55 air raids, and her guns downed a Kamikaze. The cutter Taney, serving as a combat information vessel, went to general quarters 119 times in 45 days. After being credited with downing four Kamikazes, she splashed a Japanese seaplane.

While Coast Guardsmen played a critical role in the great island-hopping push across the Pacific, many of their comrades served staunchly with the Allied armies fighting to free Western Europe from Nazi domination.

When the British, American, and Canadian armies landed in Normandy on the gray, windy morning of June 6, 1944, U.S. Coast Guard units were in the forefront, stronger than in any previous operation and concentrated off Utah and Omaha beaches. Besides the attack transports Samuel Chase, Joseph T. Dickman, and Bayfield, the Coast Guard fleet included 10 tank landing craft, four of which were assigned to the British assault forces, 25 infantry landing craft, and a flotilla of 60 83-foot wooden cutters. The Coast Guard rescue flotilla had been dispersed among the task forces when the 5,000-ship armada moved across the English Channel.

All of the Coast Guard-manned LSTs and LCIs present at Normandy had taken part in the Sicilian and Italian invasions. Coast Guardsmen manned 97 vessels at Normandy, not including landing craft carried by the transports. They crewed landing ships and landing craft at all five invasion beaches, Utah and Omaha (American), and Gold, Juno, and Sword (British and Canadian).

There was fierce resistance at Omaha and the British beaches, and several Coast Guard landing craft were damaged by mines and enemy shellfire, with the loss of many seamen. Four Coast Guard-manned LCIs were destroyed, but some of the damaged ones were salvaged by their resourceful crews and used again. Meanwhile, the 60 rescue cutters ranged across the length of the five beaches and provided an invaluable service. They picked up 400 Allied soldiers and sailors from the cold Channel waters on D-Day and more than 1,000 during the next three weeks. Despite the losses, the June 6 landings proved far more successful than had been predicted.

Late in June, a Coast Guard officer had a remarkable experience as Lieutenant General J. Lawton Collins’s U.S. VIII Corps was about to capture the strategic port of Cherbourg on the Cotentin Peninsula. Lieutenant Commander Quentin R. Walsh, a port specialist, and Navy Lieutenant Frank Lauer, a Seabee officer, entered the Fort du Homet stronghold at Cherbourg before its German garrison had surrendered. When within shouting distance, the two Americans told the Nazis that all resistance in the city had ended. They were not believed, and the Germans covered them with machine guns. But they held their fire, believing that a large patrol was following the two officers.

Only after accepting an invitation to view the situation in the city did the Germans in the fort realize that Cherbourg had fallen. Walsh and Lauer took 300 soldiers prisoner and liberated 50 American paratroopers who had been held captive there since D-Day. Walsh was awarded the Navy Cross.

Just over two months after the Normandy landings, Coast Guardsmen took part in their last major operation of the European war, the great Allied invasion of southern France (Operation Dragoon) on August 15, 1944. After heavy naval and air bombardment and flanked by Free French Commandos and U.S. Rangers and paratroops, assault troops of Lieutenant General Alexander M. “Sandy” Patch’s U.S. Seventh Army and General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s French II Corps went ashore between Cannes and Rade de Hyeres. Under the command of Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, more than 800 American, British, Free French, and Canadian battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and escort carriers supported the landings. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill watched the invasion from aboard a Royal Navy destroyer.

Among the large armada of landing craft were the Coast Guard-manned transports Bayfield, Samuel Chase, Joseph T. Dickman, and Cepheus, the Navy transports Barnett, Charles Carroll, Arcturus, and Betelgeuse with some Coast Guardsmen in their crews, the 327-foot cutter Duane, and Coast Guard-manned infantry and tank landing craft, including veterans of the Sicily and Italy invasions. There was only sporadic fire from enemy shore batteries, and the Riviera landings went smoothly. The only casualty was an LST which was hit and had to be beached.

During the war, the Coast Guard added some footnotes to naval history. In 1943, the weather ship Sea Cloud, a converted yacht that had belonged to Joseph E. Davies, President Roosevelt’s ambassador to Russia, became the first racially integrated vessel in U.S. naval service. In June 1944, the USCGC Cobb, a converted merchantman, was the site of the first landing of a helicopter on board a ship.

The Coast Guard performed all manner of gallant service from 1941 to 1945, yet its personnel, like those of the Merchant Marine, were among the war’s unsung heroes. As Admiral Nimitz observed, the Coast Guard “sometimes lost its identity because it was grouped with the Navy.” But he was unstinting in his praise for the service’s efficiency, dependability, and “selfless devotion to duty.”

Returned to the Treasury Department by the Navy on January 1, 1946, the Coast Guard resumed its longtime law enforcement and search and rescue functions. It also pioneered and developed electronic aids to navigation, collected weather and scientific data, maintained icebreaking patrols at both poles, in the Great Lakes, and on other inland waterways, enforced harbor, Merchant Marine, and boating safety regulations, and intercepted refugees and drug smugglers.

Its 82-foot cutters and large ships were busy during the red scare and Caribbean crises of the early 1950s, and more than 50 craft and 8,000 Coast Guardsmen saw action in the brown water war in South Vietnam. They destroyed almost 2,000 Communist vessels at a cost of seven deaths and 53 wounded.

The late Michael D. Hull wrote for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resided in Enfield, Connecticut.

I was disappointed that this story did not note that coast guard ran assault boats across many rivers under artillery, mortar, and small arms on the army’s assault East across Europe in WWII. (Per other warfare history articles). Sorry, I was Army and wanted to give credit where credit is due. The great American Arsenal has saved many of us. Think about something as simple as the factory that made boots or socks that prevented trench foot and frost bite. Age, brings much understanding and appreciation of how each of us contributes. Thank you all on this Memorial Day!