By Michael E. Haskew

Despite more than a decade of triumphs in Asia and the Pacific, by the spring of 1942 the Japanese military establishment was in a somber mood. Although the empire stretched from the Dutch East Indies to the Solomon archipelago, encompassing tiny Wake Island nearly 2,000 miles distant in the Central Pacific and occupying great swaths of Chinese territory, its long-term security remained tenuous at best.

The military prowess of the United States in the region had been crippled by the devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, the capture of Wake Island, and the disastrous fall of the Philippines. Nevertheless, in mid-April 1942, American planes under the command of Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle seemingly came out of nowhere and bombed Tokyo. Early the next month, a Japanese offensive against Port Moresby on the southeastern tip of New Guinea was thwarted with the unexpected defeat of the Imperial Navy at the Battle of the Coral Sea.

While the U.S. Navy had been crippled at Pearl Harbor, it was readily apparent to senior Japanese naval commanders that the Americans were far from finished. The repair facilities at Pearl Harbor had survived the attack relatively undamaged, and vast stores of fuel oil were untouched. No American aircraft carriers had been present at Pearl Harbor, and their threat to future Japanese operations demanded immediate attention.

Japanese grand strategy called for maintaining an offensive posture. The setback at Coral Sea and the growing concern following the Doolittle raid heightened the sense of urgency surrounding the next major Japanese move. Slated for early June, it was an elaborate plan to capture Midway atoll, approximately 1,150 miles west of Hawaii, and to seize of the islands of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians far to the north.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet, had favored the Midway operation from the beginning. At 58, Yamamoto was familiar with the United States, having studied at Harvard University and served as a naval attaché in Washington, D.C., in the 1920s. A combat veteran, he had lost two fingers from his left hand at the epic Battle of Tsushima Strait during the Russo-Japanese War. An advocate of naval air power, he had earned his pilot’s wings at the advanced age of 40. Poker and other card games were favorite pastimes, and Yamamoto had developed a professional reputation as a risk taker.

Japanese seizure of Midway was expected to achieve three key strategic objectives. The perimeter of the empire would be expanded, improving security. The threat to Hawaii would intensify. And the Americans would be compelled to fight for Midway, committing their precious aircraft carriers to the effort, which Yamamoto was confident would result in their destruction.

As the Midway operation took shape, Yamamoto’s principal adversary, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, had been in command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet for only five months. A native Texan, Nimitz possessed the even temperament and quiet optimism that were critically needed after eight American battleships had been seriously damaged or mired on the shallow bottom of Pearl Harbor. But Nimitz also possessed an aggressive tendency that compelled him to confront the Japanese as soon as conditions were reasonably favorable. Where Yamamoto was a gambler prone to overconfidence, Nimitz was a master of the calculated risk.

Considerable uncertainty existed among the Americans as to exactly where the next Japanese blow would fall. An intelligence coup gave Nimitz the invaluable knowledge that the target was Midway. At Station Hypo on the island of Oahu, Lt. Cmdr. Joseph J. Rochefort ran a crew of cryptanalysts who succeeded in cracking much of the Japanese Navy’s operations code, JN-25B. Rochefort’s people were eventually reading as much as 85 percent of some Japanese message traffic. As a flurry of Japanese radio communications picked up, Rochefort noticed numerous references to a location known as “AF.” Eager to confirm his suspicion that AF was Midway, Rochefort instructed the Midway garrison to send a false message to Pearl Harbor that the atoll’s freshwater condenser had broken down. The message was transmitted and the enemy took the bait. Soon, a Japanese message removed all doubt as to the identity of AF.

Although Nimitz now knew that the Japanese intended to capture Midway, he still confronted many problems. The Japanese carriers and their veteran air crews were a formidable foe. The Japanese also maintained a decided advantage in surface warships. Perhaps most disconcerting was the fact that American carrier strength remained impaired. The 37,000-ton Saratoga was in dry dock at Bremerton, Washington, for repairs to damage sustained by a torpedo hit from a Japanese submarine on January 11. Her sister ship, Lexington, had been sunk on May 8 at Coral Sea. The 19,800-ton Yorktown had taken a single bomb during the Coral Sea action and limped into Pearl Harbor on May 22, trailing a 10-mile oil slick. This left Enterprise and Hornet, both of the Yorktown class, as the only unscathed American carriers in the Pacific. To make matters worse, the most experienced and aggressive carrier commander in the U.S. Navy, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, was in a Hawaiian hospital suffering from a debilitating outbreak of dermatitis.

It was estimated that 90 days would be needed to repair Yorktown. Nimitz gave her skipper, Captain Elliott Buckmaster, a mere 72 hours to get the carrier ready for action. Working around the clock, electricians, ship-fitters, carpenters, and welders patched up the carrier. On May 28, Hornet and Enterprise sailed out to defend Midway as the nucleus of Task Force 16. Floating free from dry dock, Yorktown steamed out of Pearl Harbor the next day as the flagship of Task Force 17.

In overall tactical command of the American forces was Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, a capable commander with limited experience in carrier aviation who had led the U.S. task force at Coral Sea. As he lay frustrated in a hospital bed, Halsey recommended that Nimitz appoint Admiral Raymond A. Spruance as his replacement to lead Task Force 16. Spruance had earned Halsey’s respect while commanding a cruiser escort during earlier operations. While Spruance had no carrier aviation experience, other members of Halsey’s command group, particularly chief of staff Captain Miles Browning, did.

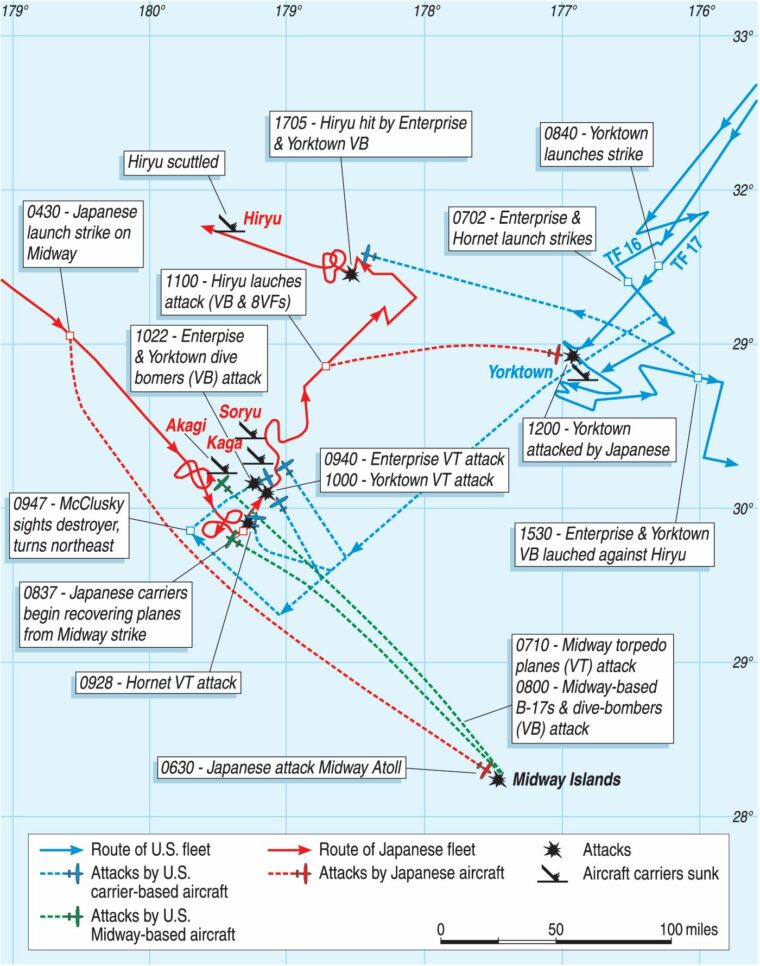

Nimitz ordered the two task forces to rendezvous 325 miles northeast of Midway at a location named Point Luck. From there, they would attack the Japanese carriers while the enemy planes were away softening up Midway in preparation for landings on the atoll’s two islets, Sand and Eastern. Along with Hornet and Enterprise, Spruance commanded five heavy cruisers, a single light cruiser and nine destroyers. Fletcher’s screening force for Yorktown included two cruisers, and six destroyers. In the Aleutians, Admiral R.A. Theobald commanded five cruisers and 13 destroyers.

Yamamoto’s penchant for complex planning was evident at Midway. The operation would begin on June 3 with an air raid on the American base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians. He expected the Americans to be caught off guard by the Aleutian feint and either rush northward to defend Alaskan territory or remain on guard at Pearl Harbor. In either case, Yamamoto did not expect substantial opposition to the occupation of Midway. When Nimitz did act, Yamamoto believed it would be several days too late. The occupation of Midway would be a fait accompli. The naval forces involved in the Aleutian thrust would be positioned to intercept any move northward, while the Midway forces would be free to take on the Americans in a decisive surface battle. Yamamoto counted on the firepower of the Japanese battleships and cruisers to finish off any American warships that escaped the ravages of his carrier planes.

Yamato assembled an awesome array of naval power to execute his master plan. No fewer than eight carriers, 11 battleships, 20 cruisers, 60 destroyers, and 15 submarines, along with transports and other support vessels, were involved. The Japanese command was divided into numerous major components, some of which were subdivided into smaller units with specific tasks. The heart of the fleet consisted of four of the six aircraft carriers of the Kido Butai, or Striking Force, that had attacked Pearl Harbor the previous December. Under the command of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, these included his flagship, the 36,500-ton Akagi, as well as the 38,800-ton Kaga, 15,900-ton Soryu, and 17,300-ton Hiryu. These were accompanied by two battleships, three cruisers, and 11 destroyers.

The Japanese main body included three new battleships, a light carrier, a cruiser, and eight destroyers. Yamamoto himself was in command aboard the mighty battleship Yamato, displacing more than 68,000 tons with a main armament of massive 18.1-inch guns. A second force, under Admiral Takasu Shiro, sailed with Yamamoto and was to take up station to support the Aleutian forces if necessary with four battleships, two cruisers, and 12 destroyers. The Midway invasion force, commanded by Admiral Nobutake Kondo, included a carrier, troop transports, battleships, and cruisers to provide fire support. The Northern Force, under Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya, consisted of two carriers, three cruisers, and the troops that eventually would occupy Attu and Kiska.

On May 27, Navy Day for the Combined Fleet in commemoration of the great victory at Tsushima 37 years earlier, Yamamoto’s main force and the Kido Butai under Nagumo sailed from their anchorage at Hashirajima, in the Inland Sea south of the naval base at Kure and the city of Hiroshima. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, the naval aviator who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor, was aboard Akagi, but would not be of much help. The most accomplished air leader in the Japanese Navy, Fuchida was confined to the carrier’s sick bay with appendicitis. Commander Minoru Genda, who planned the tactical element of the Pearl Harbor attack, was also aboard Akagi but he was suffering from pneumonia, and his contribution to the Midway operation likewise was greatly diminished.

Altogether, the four carriers of Nagumo’s striking force mustered more than 240 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, Aichi D3A1 Val dive bombers, and Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bombers. Aboard the three American carriers were a roughly equivalent number of Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters, Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, and Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers. A hodgepodge of about 100 planes was based at Midway.

The Japanese Zero had earned a reputation as the finest fighter plane in the Pacific, nimble and armed with both 7.7mm machine guns and 20mm cannons. Its Achilles heel was a lack of armor protection for the pilot and the absence of self-sealing gasoline tanks. A few hits from the .50-caliber machine guns of an American F4F were often enough to send a Zero down in flames. However, its speed and maneuverability made the Japanese fighter a deadly opponent.

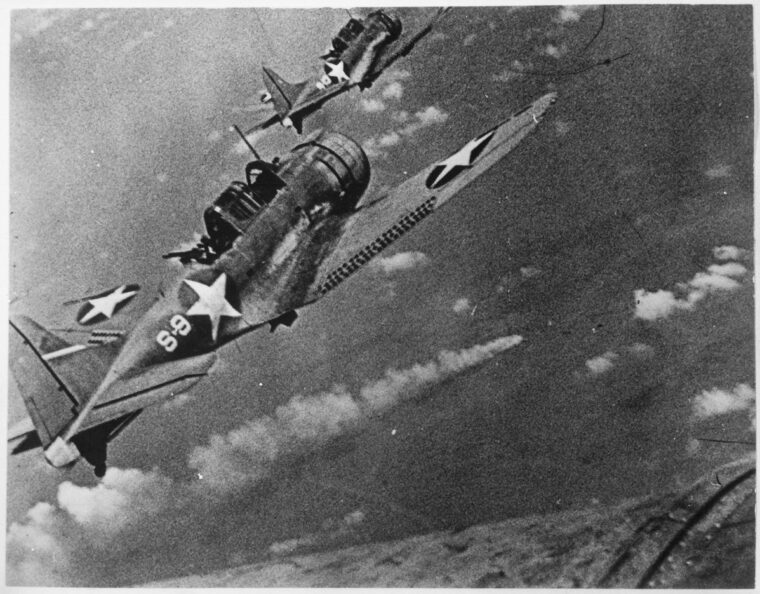

American fighter pilots knew their Wildcats could not turn with the Zeros and were reluctant to engage in prolonged dogfights with their Japanese adversaries. Instead, they attempted to attack from above, diving on Zeros with guns blazing and using speed to regain altitude. The Dauntless was a stable dive-bombing platform that could absorb tremendous punishment and still bring its pilot home. By contrast, the slow, short-range Devastator was woefully inadequate, and its crews would pay a terrible price at the hands of the Zeros.

Under the command of Marine Captain Cyril Simard, Midway was defended by 3,652 men of the Sixth Marine Defense Battalion, supplemented by elements of the Third Marine Defense Battalion and two companies of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion. Its air group included only six operational Wildcat fighters and 21 obsolete Brewster Buffalo aircraft. Among the bombers were 18 Dauntlesses and 21 outdated Vought SB2U Vindicators, 15 four-engine Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, four Martin B-26 Marauders modified to carry torpedoes, and the six brand-new TBF Avengers. A total of 29 long-range Consolidated PBY Catalina patrol planes were also available.

At 3 am on June 3, Midway-based pilots and crewmen of combat air-patrol planes and 22 long-range Catalina flying boats detailed to carry out reconnaissance flights were roused from their bunks. By 4:15 they were climbing into the morning sky. The Catalinas were to cover search areas of approximately 700 miles each, totaling thousands of square miles of ocean. As the Catalinas neared the limits of their range that morning, Ensign Charles R. Eaton and his crew spotted several Japanese vessels and radioed the first confirmed sighting of the enemy: “Two Japanese cargo vessels sighted bearing 247 degrees, distance 470 miles. Fired upon by AA.”

Minutes later, the PBY piloted by Ensign Jack Reid, having already extended the outward leg of its search, was nearing a turn for home when three crewmen almost simultaneously spotted the wakes and dim silhouettes of Japanese ships. Reid dashed off a somewhat cryptic message: “Sighted main body.” This was quickly followed by “Bearing 262, distance 700.” Back at Midway, Simard asked for ship types, course, and speed. Reid turned and trailed the Japanese, attempting to stay out of sight and comply with Simard’s orders. An agonizing interval followed before Reid confirmed 11 ships, including a small aircraft carrier, seaplane carrier, two battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. Actually, Reid had not spotted Yamamoto’s main body; the ships were heavyweights of the Midway invasion force under Admiral Kondo. Eaton had detected the minesweeper group, also part of the invasion force. Nevertheless, it was enough for Simard to take action.

At 12:30 pm, nine B-17s of the 431st Bombardment Squadron took off to attack the Japanese. Four hours later, the big bombers spotted the Japanese transport group, under Admiral Raizo Tanaka, dropped their 600-pound bombs from altitudes of at least 8,000 feet, and headed for home. Reports of hits proved inaccurate, and no casualties were sustained on either side, but the Japanese knew that they had been discovered. At 1:30 am on June 4, three Catalinas armed with torpedoes attacked the transport group once again. This time, one succeeded in putting a torpedo into the tanker Akebono Maru. Twenty-three Japanese sailors were killed or wounded. Meanwhile, the Japanese had already struck the first blow of the battle as 14 bombers and three fighters attacked Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians in the early morning hours of June 3, destroying a barracks, fuel tank farm, and other installations and killing 25 Americans.

Still unaware that three enemy aircraft carriers were in the vicinity of Midway and had swung northwest toward the most likely approach route of his own striking force, Nagumo turned his carriers into the wind and began launching an air strike against Midway to remove the threat of air attack from the atoll and soften up its defenses for an amphibious landing. As Sweeney’s B-17s were taking off to attack Tanaka, 108 Vals, Kates, and Zeros rose from the decks of the Japanese carriers. The planes were under the command of Lieutenant Joichi Tomonaga, a veteran pilot selected to replace the ailing Fuchida as strike leader. Nagumo retained half his aircraft, armed with torpedoes, to meet the threat of any American surface ships.

At 5:20 am, Midway reconnaissance once again hit pay dirt. Lieutenant Howard F. Ady reported sighting a Japanese aircraft carrier and followed that with a report that enemy aircraft were approaching the atoll. Another search plane, piloted by Lieutenant (j.g.) William A. Chase, spotted the inbound Japanese raid at 5:45 and radioed, “Many planes heading Midway, bearing 320 degrees, distance 150.” Within minutes, Midway’s antiaircraft defenses were on alert and every aircraft was sent aloft. Midway radar picked up the Japanese at a distance of 93 miles.

During the sharp aerial battle that ensued, 24 American fighters were either shot down or seriously damaged. Under the command of Major Floyd B. “Red” Parks, the pilots of Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-221 fought bravely but could not turn back the Japanese onslaught. Parks himself was among the casualties.

Tomonaga led his planes into withering fire from the Midway defenders and destroyed the seaplane hangar, fuel dump, powerhouse, and freshwater processing facility. Twenty-four Americans were killed and 18 wounded. The Japanese lost 11 attacking planes; another 40 were damaged, some badly enough that they could no longer take part in the battle. More distressing for the Japanese was the assessment of the raid itself. The airstrip at Midway remained functional, and Tomonaga radioed that a second strike was required.

Ady’s sighting of a Japanese carrier had fixed the enemy’s location for Fletcher and Spruance while also alerting Simard, who threw every available Midway-based aircraft at the Carrier Striking Force. More than 50 planes without fighter escort mounted four separate attacks against Nagumo’s warships. Six U.S. Navy TBF Avengers and four Army Air Corps B-26 Marauders attacked a few minutes after 7 am, followed less than an hour later by the Marine Corps Dauntless dive bombers of VMSB-241. An additional 14 B-17s attacked from 20,000 feet, their bristling guns keeping the Zeros at bay but scoring no hits.

Eleven Vindicator dive bombers made the final morning attack, targeting Japanese battleships. Their commander, Major Benjamin W. Norris, burst through cloud cover and found himself some distance away from the carriers. Norris knew that his elderly planes, constructed partially of fabric, could not stand up to heavy antiaircraft fire from the carriers and chose to glide bomb the nearest targets. Near misses rocked Haruna, and one American bomb narrowly missed the fantail of Kirishima, but not a single hit was scored. At least 19 American planes were shot down, and the Japanese lost three Zeros.

Nagumo worried that the surviving Midway-based aircraft continued to pose a threat and had to be neutralized. When he received Tomonaga’s request for a second strike at about 7:15 am, it was all he needed to hit Midway again. The Kates of the first raid had been supplied by Soryu and Hiryu, while the dive bombers had taken off from Akagi and Kaga. Nagumo ordered that the Kates aboard Akagi and Kaga have their torpedoes replaced with high-explosive bombs. The Vals sitting on the hangar decks of Soryu and Hiryu had not yet been armed, and he ordered them equipped with high-explosive bombs for land targets on Midway rather than the armor-piercing types used against enemy ships.

The failure of the Japanese to deploy sufficient numbers of reconnaissance aircraft now came back to haunt Nagumo. The launching of some of the Japanese scout planes had also been delayed, due to engine or catapult problems, and one of these, Number 4, had taken off late from the heavy cruiser Tone. As the plane reached the end of its 300-mile search radius, the pilot spotted the wakes of several ships. There was little doubt that these were American.

Consternation gripped the officers aboard Akagi when the news was received. “When it reached Admiral Nagumo and his staff on Akagi’s bridge,” Fuchida wrote, “it struck them like a bolt from the blue. Until this moment no one had anticipated that an enemy force could possibly appear so soon, much less suspected that enemy ships were already in the vicinity waiting to ambush us. Now the entire picture was changed.”

At 8:20, Scout Number 4 relayed more incredible news: “Enemy force accompanied by what appears to be aircraft carrier bringing up the rear.” Nagumo confronted a major dilemma. The rearming of the planes for the second Midway raid would take an hour to complete. At about the same time, Tomonaga’s planes would be returning from the first Midway strike, low on fuel and some damaged. These planes would have to be recovered quickly. To complicate matters, his carriers were under intermittent air attack by American planes from Midway, preventing deck crews from adequately preparing to launch or recover their own aircraft.

Nagumo, paralyzed by indecision, allowed precious minutes to tick away before issuing new orders. Once the planes of the first Midway strike were recovered, he intended to turn northeast, racing at 30 knots to close with the Americans and destroy any enemy carriers. He estimated that 89 planes would be available for launch at approximately 10:30 am. Time, however, was running out for Nagumo and his striking force.

On the evening of June 3, hours after Reid first sighted Japanese warships, Task Forces 16 and 17 closed their distance from Midway to 200 miles and maintained a course to the north of the atoll. Already alerted by Nimitz in far-off Hawaii that Reid’s sighting was not the Japanese main body, Fletcher and Spruance still expected the Japanese carriers to approach Midway from the northwest. Radio operators aboard Enterprise picked up Ady’s message identifying a Japanese carrier early on the morning of June 4. Moments later, another message from Chase confirmed the presence of at least one more carrier.

Fletcher weighed his options. At 6:07 am, four minutes after receiving the latest report on the Japanese carriers, he ordered Spruance with Enterprise and Hornet to “proceed southwesterly and attack enemy carriers when definitely located. I will follow as soon as planes recovered.” Fletcher had set the stage for Spruance to make the most momentous command decision of the carrier war in the Pacific. Spruance calculated that within three hours his carriers would be approximately 100 miles from Nagumo’s ships—but how long could he remain undetected by the Japanese? Aware that Japanese planes had already attacked Midway, Spruance conferred with Browning and decided to launch every available plane from Enterprise and Hornet. Launch time was 7:02 am, and the distance of about 170 miles was at the extreme limit of the range of the carrier planes.

It was a risk, but Spruance knew that the Japanese carriers would have to steam toward Midway for some time to recover the planes returning from Tomonaga’s raid. If he had made the right call, American planes could well be in position to attack the Japanese carriers with their decks full of unready aircraft.

Launching carrier planes was usually a well-choreographed endeavor, but several delays kept the Dauntless dive bombers circling above Task Force 16, wasting precious fuel, while engine trouble was corrected and Wildcat fighters and Devastator torpedo bombers were brought up from the hangar decks. Spruance became impatient and ordered the Enterprise dive bombers, 37 Dauntlesses of Bombing 6 and Scouting 6 under Lt. Cmdr. Clarence W. “Wade” McClusky, to proceed on their own. When launch operations were finally completed, 67 dive bombers, 29 torpedo planes, and 20 fighters were in the air. Eighteen Wildcats remained on combat air patrol above Task Force 16.

Fletcher followed Spruance on a course of 240 degrees and held his planes aboard Yorktown for two additional hours in case a second Japanese carrier group was spotted. Fletcher was still smarting from erroneous information during the Battle of the Coral Sea that had caused him to launch all planes against a secondary target, the light carrier Shoho. By 8:40 am, Fletcher had received no additional reports of Japanese activity and turned Yorktown into the wind to launch 17 dive bombers, 12 torpedo planes, and six fighters. As the sun climbed higher on the morning of June 4, air temperatures hovered around 70 degrees and visibility was virtually unlimited, with only a few high clouds in the tropical sky.

The last Japanese plane returning from the Midway strike landed a few minutes after 9 am, and Nagumo ordered his ships to execute the predetermined change of course to the northeast. The decks of the four Japanese carriers were beehives of activity, some planes being raised and lowered on elevators while others were armed and fuel lines stretched to fill empty tanks.

Nagumo’s course change did pay one dividend: the 35 Dauntlesses and 10 Wildcats of Hornet’s Bombing 8, Scouting 8, and Fighting 8 reached the anticipated point of interception and found nothing but open ocean. Commander Stanhope Ring led the planes toward Midway in search of the enemy fleet, but came up empty. The entire flight missed the battle, several planes landing to refuel at Midway while a number of others were forced to ditch.

McClusky, too, had flown toward the expected position of the Japanese carriers. When he found nothing, the commander of the Enterprise air group, who had turned 40 years old just a few days earlier, opted to maintain course for another 35 miles, rather than turning back toward Midway or his carrier. McClusky headed north at 9:35 am. Twenty minutes later, he spotted the wake of a Japanese destroyer, Arashi, just coming off a depth-charge attack on the American submarine Nautilus. McClusky correctly assumed that the destroyer was rushing to catch up with Nagumo. At 10:02, he spotted the Japanese quarry 35 miles to the northeast.

Within seconds, Lt. Cmdr. Maxwell F. Leslie, leading Yorktown’s Bombing 3, made visual contact as well. McClusky and the Enterprise Dauntlesses were at 19,000 feet, while Leslie’s Yorktown dive bombers were at 14,500. In the distance, they saw black puffs of antiaircraft fire and streaks of flame as burning planes fell from the sky. Nagumo’s ships were maneuvering violently to avoid torpedo attacks from three squadrons of lumbering American torpedo planes.

Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron led Hornet’s Torpedo 8 in the first attack against Nagumo by American carrier planes. At 9:20 am, Waldron picked out the nearest Japanese carrier, Soryu, and began his run. Moments later, his last words were overheard by a member of another squadron: “Watch those fighters! How am I doing? Splash! I’d give a million to know who did that! My two wingmen are going in the water!”

During the next 20 minutes, all 15 Devastators of Torpedo 8 fell victim to Zeros or heavy antiaircraft fire, many without launching their torpedoes. Ensign George Gay was the lone survivor among 30 naval aviators. Gay floated in the water until the following afternoon, when he was picked up by a patrolling Catalina. The previous night, Waldron had updated his attack plan and written a poignant and prophetic message to his men: “Just a word to let you know that I feel we are all ready. We have had a very short time to train and we have worked under the most severe difficulties. But we have done the best humanly possible. I actually believe that under these conditions we are the best in the world. My greatest hope is that we encounter a favorable tactical situation, but if we don’t, and the worst comes to worst, I want each of us to do his utmost to destroy our enemies. If there is only one plane left to make a final run-in, I want that man to go in and get a hit. May God be with us all. Good Luck, happy landings, and give ‘em hell.”

Torpedo 6 from Enterprise attacked next. Fourteen Devastators led by Lt. Cmdr. Eugene E. Lindsey were without fighter cover, and the Zeros pounced like wolves. In seconds, Lindsey was shot down; nine others followed quickly. The four surviving torpedo bombers managed to escape only because the Japanese pilots were so busy with new reports of incoming American aircraft.

At 10 am, Lt. Cmdr. Lance E. Massey, at the head of Torpedo 3 from Yorktown, sighted the Japanese warships. Zeros jumped the six escorting Wildcats of Fighting 3, under Commander John S. Thach, and a wild melee ensued. Five torpedoes were launched at the Japanese carrier Hiryu from starboard, but no hits were scored. Torpedo 3 lost 10 of its 12 Devastators.

Altogether, 41 American torpedo planes had attacked Nagumo’s carriers. Thirty-five were shot down. Of the 81 pilots and rear gunners that flew into action, 69 were killed, but the slaughter of the torpedo squadrons was not in vain. In their frantic maneuvering to avoid the attacks, the Japanese had been unable to move their own aircraft to the flight decks for a strike at the American carriers. The Zeros still in the air had been heavily engaged and were low on fuel and ammunition. Even worse, while chasing the slow Devastators, the Japanese planes had been pulled down to low altitude and could not react quickly enough to defend against the dive bombers of McClusky and Leslie, who were spoiling for a fight.

Just before Massey’s ill-fated torpedo attack on Hiryu, McClusky and the Dauntlesses of Scouting 6 and Bombing 6 pushed over into steep dives toward Kaga. Although their intent had been to split the squadrons and attack Kaga and Akagi simultaneously, a mistake in communications sent all the dive bombers hurtling toward the same target. Lieutenant Richard Best, commander of Bombing 6, realized the error and aborted his dive along with two other VB-6 Dauntlesses. The three diverted to Akagi. At the same time, Leslie’s dive bombers from Yorktown approached Soryu from the northeast.

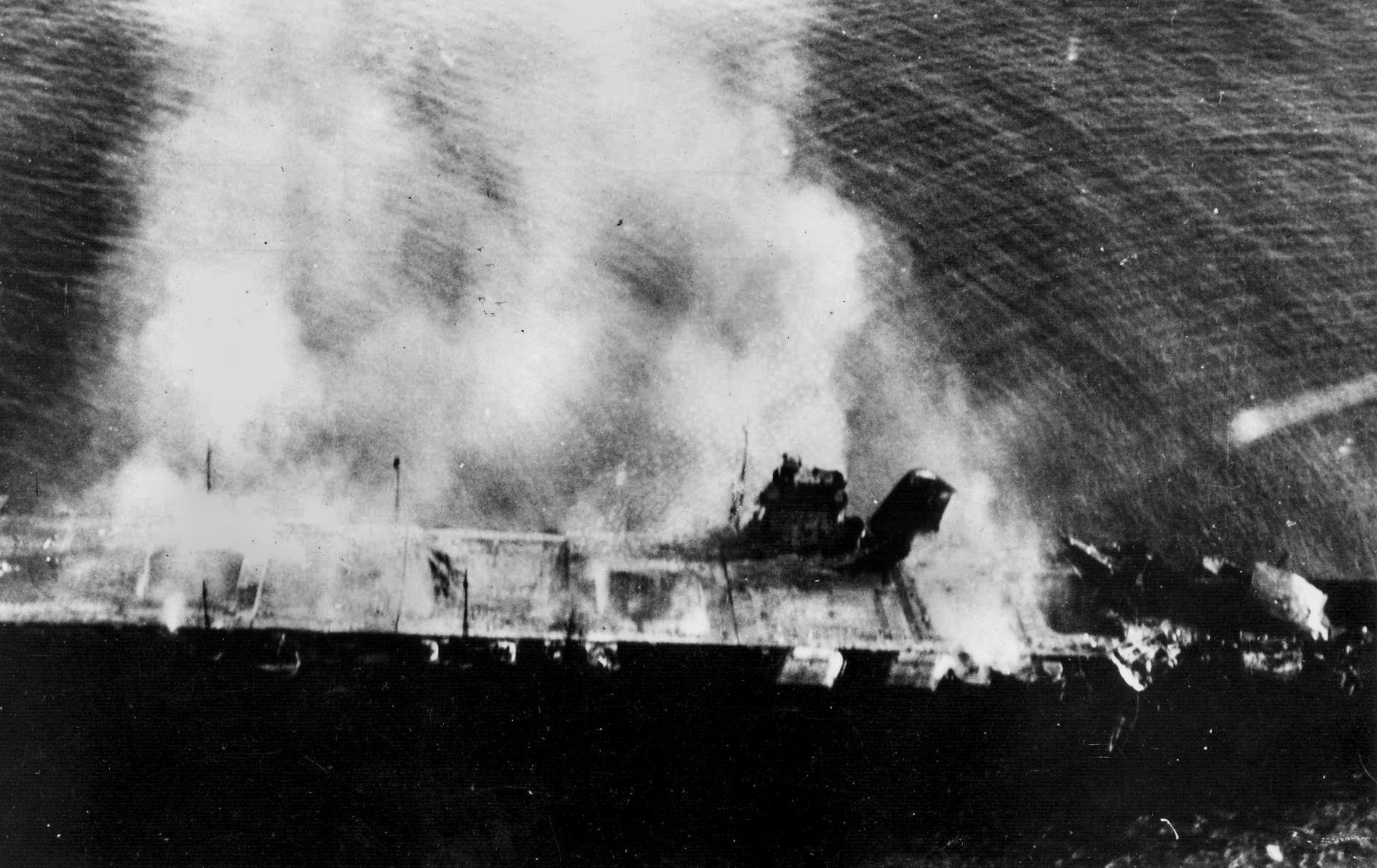

Within five minutes, three Japanese carriers had become blazing pyres. The flight deck of Akagi was packed with aircraft ready to take off and attack the American carriers. “The Air Officer flapped a white flag, and the first Zero fighter gathered speed and whizzed off the deck,” Fuchida remembered. “At that instant a lookout screamed: ‘Hell-divers!’ I looked up to see three black enemy planes plummeting toward our ship. The plump silhouettes of the American ‘Dauntless’ dive bombers quickly grew larger, and then a number of black objects suddenly floated eerily from their wings. Bombs! Down they came straight toward me! I fell intuitively to the deck and crawled behind a command post mantelet.”

The first bomb was a near miss, its splash drenching everyone on the bridge. Best’s bomb then hit squarely on the amidships elevator and penetrated to the hangar deck. In their haste, crewmen had not secured the bombs they had removed earlier. As these cooked off, Akagi was wracked by internal explosions. Fires raged out of control and sealed many passages below the bridge. A third bomb struck along the edge of the flight deck’s port side. Nagumo transferred his flag to the light cruiser Nagara. Fuchida broke both ankles and barely escaped with his life.

Akagi lost power and was finally abandoned at 5 pm. Yamamoto himself finally ordered destroyers to scuttle the blackened hulk the following morning. Remarkably, only 263 men were killed. The fate of Kaga was similar. McClusky’s dive bombers screamed down at an angle of roughly 70 degrees. Kaga’s air officer, Captain Takahisa Amagai, observed, “Splendid was their tactic of diving upon our force from the direction of the sun, taking advantage of intermittent clouds.”

Lieutenant Earl Gallaher dropped his 1,000-pound bomb on the starboard flight deck, immediately turning planes into torches. Two more bombs hit near the forward elevator, igniting a gasoline truck that showered the bridge with flaming shrapnel and killed everyone present. A fourth hit squarely amidships on the port side. Efforts to save the ship were futile, and 811 men perished before torpedoes from destroyers sent Kaga to the bottom at 7:25 pm.

When Leslie’s 17 planes attacked Soryu, only 13 of them still carried bombs. Electric arming switches had malfunctioned, and four bombs had fallen harmlessly into the sea. Leslie blazed away at Soryu’s bridge until his guns jammed. Lieutenant (j.g.) Paul “Lefty” Holmberg dropped his bomb from less than 3,000 feet and was satisfied with a hit amidships that exploded on the hangar deck and catapulted the forward elevator against the bridge. A second bomb smashed into the flight deck and blew a Zero into the sea as it was taking off. The third bomb struck near the aft elevator. Soryu blazed from bow to stern, and 20 minutes later the order was given to abandon ship. With 718 of her crew dead, the carrier drifted and finally plunged out of sight at 7:13 pm.

As American planes dodged Zeros and headed back toward their carriers, only Hiryu emerged from the morning holocaust unscathed. Preparations to retaliate were swift, and by 10:58 am, 18 dive bombers and six fighters were in the air and heading toward Yorktown. Led by Lieutenant Michio Kobayashi, the dive bombers ran the gauntlet of Wildcat fighters and antiaircraft fire, split into two groups, and put three bombs into the carrier. The first struck the flight deck aft near the number two elevator and exploded on the hangar deck. The second penetrated the flight deck, roared through a ready room, squelched the fires in the boilers, and damaged three uptakes. The third hit the number one elevator and exploded on the fourth deck.

Yorktown slowed to six knots and billowed smoke, but damage-control parties performed magnificently. Four hours later, the carrier was making a miraculous 19 knots. At approximately 2:30 pm, however, the redoubtable Tomonaga, flying a damaged Kate and fully aware that a ruptured fuel tank sustained during his Midway attack meant that he could not make the return flight to Hiryu, led 10 torpedo bombers against Yorktown. Two hits on the port side knocked out the boilers again and caused serious flooding. The carrier quickly began to list. At 2:55, Buckmaster gave the order to abandon ship.

While Yorktown was under torpedo attack, word was received from one of its scout planes that Hiryu had been spotted. By 3:30, Spruance had 25 dive bombers in the air and speeding to the northwest. A half hour later, Hornet launched another 16 Dauntlesses. Yorktown’s damage control had been so effective that surviving pilots of the second Yorktown strike believed they had put a second American carrier out of action. Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi aboard Hiryu issued orders to prepare five Vals, five Kates, and 10 Zeros, all that remained of the striking force’s once-mighty air armada, to attack what he believed to be the only remaining American carrier.

McClusky had been wounded earlier in the day and could not take part in the mission against Hiryu. Command of the strike that included both Enterprise planes and refugees from the stricken Yorktown fell to Gallaher. Although Zeros were on combat air patrol, the dive bombers achieved surprise a second time and hit Hiryu with four bombs on the forward section of the flight deck, one of which blew the forward elevator out of its well and against the island. Penetrating to the hangar deck, bombs destroyed the handful of planes being readied for the next Japanese mission. A sheet of flame erupted and spread rapidly throughout the ship. Yamaguchi chose to die with Hiryu when the crew was ordered off at 4:30. A single torpedo from a Japanese destroyer was not enough to scuttle the fire ravaged carrier, which drifted until just after 9 the following morning before sinking. A total of 383 sailors were killed.

Despite the news that Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu were on fire, Yamamoto modified his plan in an attempt to retrieve victory from an apparent crushing defeat by overwhelming the Americans with his superior surface strength during a night engagement. The situation, however, was too chaotic. Moreover, Spruance would have none of it. After Yorktown was hit, Fletcher deferred to his junior admiral, and Spruance decided to retire eastward on the night of June 4. Although his decision was criticized in some quarters, his reasoning was sound. The Japanese had suffered devastating losses, but their surface strength was greatly superior to his own and Midway had to be protected. By 11:30 pm, the Japanese had made no contact with American surface units. Yamamoto was compelled to cancel the Midway operation.

Buckmaster and an intrepid salvage party of 170 sailors worked feverishly to save Yorktown during the overnight hours of June 5 and the following day. The destroyer Hammann stood by to assist, and counter-flooding corrected some of the carrier’s list. Dispatched from Pearl Harbor, the fleet tug Vireo arrived and took Yorktown in tow. It appeared that the carrier might yet live, but it was not to be. At 1:36 pm on June 6, the Japanese submarine I-168 crept to within 1,300 yards and fired a spread of torpedoes. Two struck home, sealing Yorktown’s fate. A third broke the back of Hammann, which sank in minutes. Despite such tremendous punishment, Yorktown lingered until approximately five the next morning and then settled to the bottom of the Pacific.

On the morning of June 5, Spruance and Task Force 16 waited out some bad weather and anticipated the reports of reconnaissance aircraft. Convinced that Midway was in no immediate danger, Spruance turned northwest to search for a possible fifth Japanese carrier that had been erroneously reported. Several air strikes during the day produced no appreciable results.

Closer to Midway, the Japanese heavy cruisers Mogami and Mikuma, detailed to bombard the atoll’s airstrip, received the order to retire. As they turned, an American submarine was sighted. During the ensuing evasive action, Mogami knifed into Mikuma, heavily damaging Mogami’s bow and slowing the cruiser to 12 knots. Mikuma remained to escort her sister. An American air strike that afternoon produced no hits. However, the following morning dive bombers from Hornet hit Mogami with two bombs. In short order, five bombs from Enterprise Dauntlesses plastered Mikuma. Mogami took another bomb during an afternoon attack but survived. Mikuma sank that night, losing 700 crewmen.

By the evening of June 6, Spruance had withdrawn from the battle area. Yamamoto was steaming back to Japan, contemplating his apology to Emperor Hirohito and willing to accept sole responsibility for the disastrous defeat that had befallen the Imperial Japanese Navy. The American victory at Midway was decisive. The Japanese managed to occupy the Aleutian islands of Attu and Kiska on June 7. However, they had lost the soul of their fighting force and the offensive initiative in the Pacific. Four aircraft carriers had been destroyed along with 248 aircraft. Nearly 3,100 sailors and naval aviators had been killed. The Americans had lost Yorktown, Hammann, 144 planes, and 362 dead.

In a flash, the entire course of the Pacific war had tilted in America’s favor.

The photo cited as being of Admiral Yamamoto is actually of Admiral Nagumo

Yes, you are right, and corrected now. Thanks for commenting.

Nice map. Thanks.

Amazing victory by some incredibly brave men. Where do we get such men?

One more comment.

Four admirals were later promoted to the 5-star rank: Leahy, King, Nimitz, and Halsey. Some of us think the 4th should have been Spruance rather than Halsey, however, Halsey was the Navy version of MacArthur; charismatic and popular.

A Naval Reserve officer recently pointed out to me that the Navy got it right in the end. There is a Nimitz class of ships, and a Spruance class of ships, but no Halsey class of ships.