By J.C. Hanna

The Great Depression greatly affected millions of Americans during the 1930s, and my father, Chad Hanna, was no exception. Life was extremely hard for a mother and her family of eight children whose husband and father had abandoned them. Born in 1920, Dad worked as a paper boy, hunted rabbits for food, and did whatever he could to help the family. He graduated from high school in Breckenridge, Texas, in 1936, worked for the National Youth Administration for a short time, and attended college for one semester in 1937 before the money ran out.

After working 12 hours a day and earning a daily wage of $1 as an apprentice meat cutter in Eunice, New Mexico, he was laid off in the spring of 1938. Returning home to Breckenridge, he could not find work, so he joined the Army after being rejected by both the Marines and Navy due to flat feet and an overbite. He was 18 years old when he signed up for a three-year enlistment period in Lubbock. He had to have both parents grant permission to join the military, so he had to find his father. He then went by train to Fort Bliss near El Paso, Texas, in July 1938, for recruit drill.

J.C. Hanna: What were some of the details about your time at Fort Bliss?

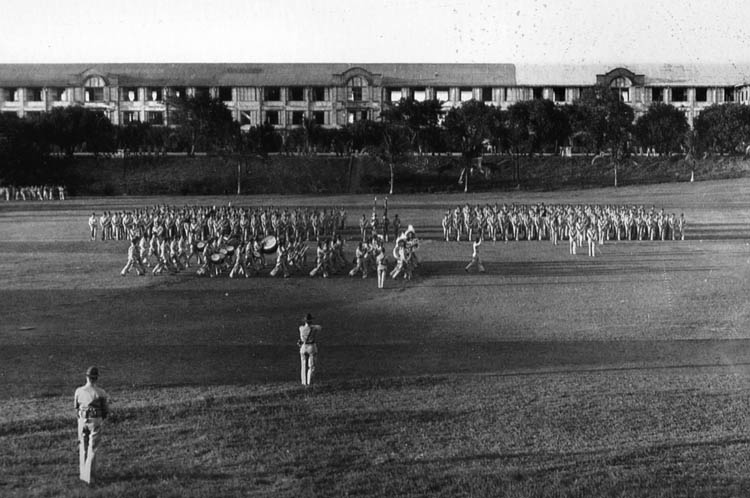

Chad Hanna: I was assigned as a buck private to the First Medical Battalion, which was part of the Post Medical Detachment. My main duty was as a chair assistant in the Dental Clinic. Everyone had recruit drill regardless of your duty, and I was posted to B Troop of the 7th Cavalry (Custer’s regiment), which was part of the 1st Cavalry Division. We had extensive mounted and foot drill over an eight-to-12- week period of time.

JCH.: Does that mean you actually rode horses?

CH: You bet. I got to be a pretty good rider; you have to remember that the gaits of a horse for military purposes are different from those of a civilian. There are only three gaits for the military: walk, trot, and run. Both the walk and trot are used for marching purposes; our post procedure for the trot was to stand up in the saddle and match the horse’s stride so there was no bumping. The run technique was only used in battle conditions; you could fire a weapon at a run, but not a gallop, so the latter pace was not used. We also had plenty of firing practice, both with a .30-caliber rifle and a .45-caliber pistol. There was no machine-gun requirement at Bliss, but I later qualified for this weapon in the Philippines.

JCH: How long were you at Fort Bliss?

CH: I worked as a dental chair assistant for about one and a half years and I had one promotion to private, 6th class specialist, during that time.

JCH: How did you end up leaving Fort Bliss?

CH: I had a good buddy named Jack Tosh, and the two of us decided we wanted to go overseas. There were four choices: Panama, Hawaii, Alaska, and the Philippines. The only openings at the time were in the Philippines, so the choice was pretty easy. I applied for and received a short discharge with a reenlistment term for another period of three years. I left Fort Bliss in late 1939.

JCH: How did you get to the Philippines?

CH: I was able to first go home to Breckenridge for a visit, and then I had to find my own way to Angel Island near San Francisco. I remember I rode the bus all the way and the fare was a grand total of $25.05. A six-week trip aboard the troopship U.S. Grant followed. We stopped en route at Honolulu and Guam. We arrived in the Philippines in mid-June of 1940.

“They’ve lost the Jap fleet again”

JCH: Where were you stationed and what were your duties?

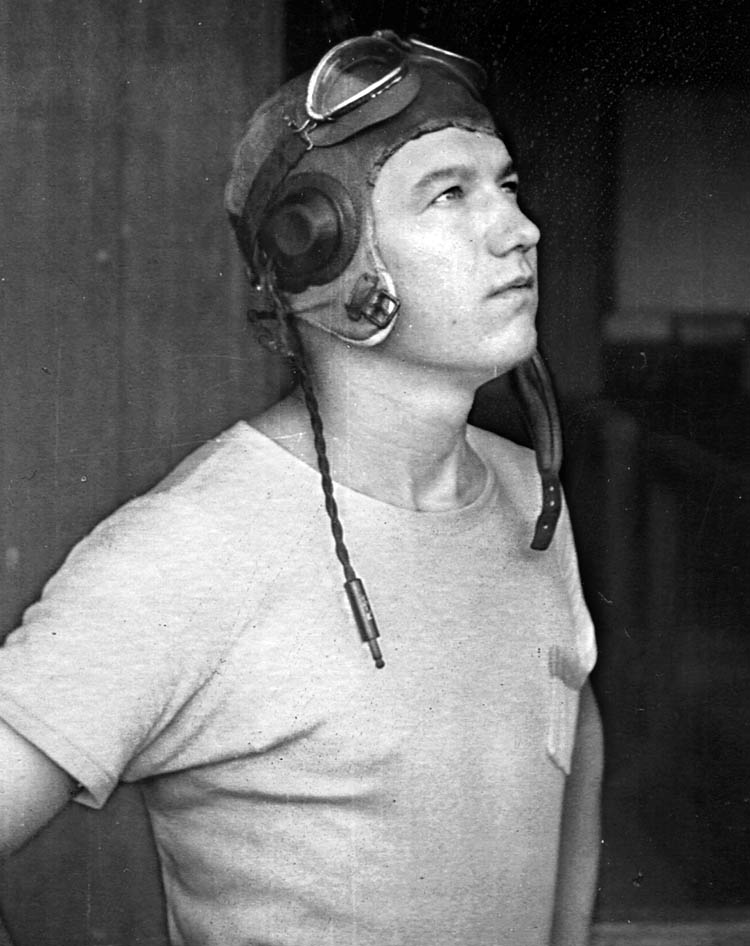

CH: Somehow I had been assigned to the Army Air Corps, and I was ordered to Nichols Field, just outside Manila. It is interesting to note that I was originally quarantined upon arrival, but I do not remember why; it was possibly due to measles. I stayed at Nichols for about three weeks and then I was sent to Corregidor for recruit drill again. We did both weapons (.45-caliber handgun, .30-caliber rifle, and .30-caliber machine gun) and drill training.

About three weeks later, I returned to Nichols Field for assignment to the Headquarters Squadron of the 4th Composite Group, composed of both pursuit and bomber squadrons. We had somewhat obsolete fighter aircraft such as the P-26A, P-35A, and P-40B; additionally, we had bombers such as the B-3A, B-10, and B-18. It was not until just before the start of the war that we received frontline aircraft like the P-40E and B-17D. Shortly thereafter, I was assigned to the Headquarters Squadron of the 24th Pursuit Group, which was made up of the 3rd, 17th, and 20th Squadrons. This group moved in July 1941 to Clark Field, about 50 miles north of Manila.

JCH: Were you at Clark when the Japanese struck on December 8, 1941?

CH: Yes, I had been promoted to corporal, and I was working as a clerk in the Group Engineering Office within the Headquarters Squadron. Nobody was particularly worried about war in the Pacific because we all thought the real war was happening in Europe. A common phrase around the base was, “They’ve lost the Jap fleet again,” meaning that nobody knew where or what the Japs were up to. Thanks to a vacancy that was caused by a transfer, I became chief clerk of the engineering office, with promotion to sergeant in the fall of 1941.

JCH: What do you remember about the attack on Clark Field?

CH: I was the only engineering person to be living in one of the hangars instead of the barracks. I was resting in my bunk just after lunch when the air raid siren sounded. Unfortunately, the majority of the 24th Group planes had been aloft most of the morning as a precaution looking for the Japs and they had landed for refueling and lunch.

Somewhere between 50 and 60 twin-engine Japanese Betty bombers hit the field; I could see them come in over the mountains. I had my steel helmet, gas mask, and .45-caliber pistol with me as I ran to a drainage ditch that was several hundred yards away. I tripped over a tent stake and I fell flat on my face, making me feel like an idiot. I made it to the ditch, which was wide, but shallow. I was able to get under the lip of the ditch as the first bombs hit.

The closest bomb fell 30 to 40 feet away with a significant spraying of dirt. The Bettys left after one pass, and Zeros [fighters] then made several low passes, strafing as they zoomed by. The overall attack lasted maybe 30 minutes. The field looked completely disabled, although we were fortunate to not have any casualties in my group. Since my hangar and the barracks were destroyed in the attack, we were organized by the first sergeant, bivouacked under trees on the other side of the runaway, and ordered to dig foxholes.

“My former unit… ended up as participants in the Bataan Death March.”

JCH: What happened during the next few weeks?

CH: Clark Field was periodically attacked by air over the next two weeks, and the Japs landed in several places on Luzon. We withdrew from Clark roughly two weeks later, and I remember having Christmas dinner out of mess trucks while we were moving down to Bataan. I was reclassified as an infantryman, and my company was renamed the Headquarters Company of the 71st Infantry Battalion. Our battalion fought in the so-called “Battle of the Pockets” near Mariveles, but the Headquarters Squadron was not sent into battle. By this time, we were directly across from Corregidor.

Along with a few others, I was ordered by the first sergeant to be “loaned to the Navy.” My new duty was to help operate the Peninsular Air Warning System in Tunnel No. 4. After being an operator for a short while, I was appointed to be a helper to the chief telephone repairman. Our job was to repair telephone lines that had been cut, which was a normal occurrence after most every Japanese bombing or artillery attack. I can remember that I was caught up on a telephone pole, completely exposed, during one Japanese bombing attack. Luckily for me, I was not hurt. We were still doing air warning work when Bataan fell. Because we were living with Navy personnel, we were very fortunate to make it to Corregidor.

JCH: So, this escape to Corregidor could be considered the first of your three lucky charms?

CH: Yes, you could say that. My former unit, the 24th Pursuit Group, ended up as participants in the Bataan Death March. I was able to avoid this terrible march by my temporary reassignment to the Navy.

Although I did not ask for this assignment and actually I was unhappy to be separated from my regular Army unit, it turned out that I was very fortunate not to be captured on Bataan, since those captured were forced to participate in the Death March with dire consequences.

JCH: What do you remember about your time on Corregidor?

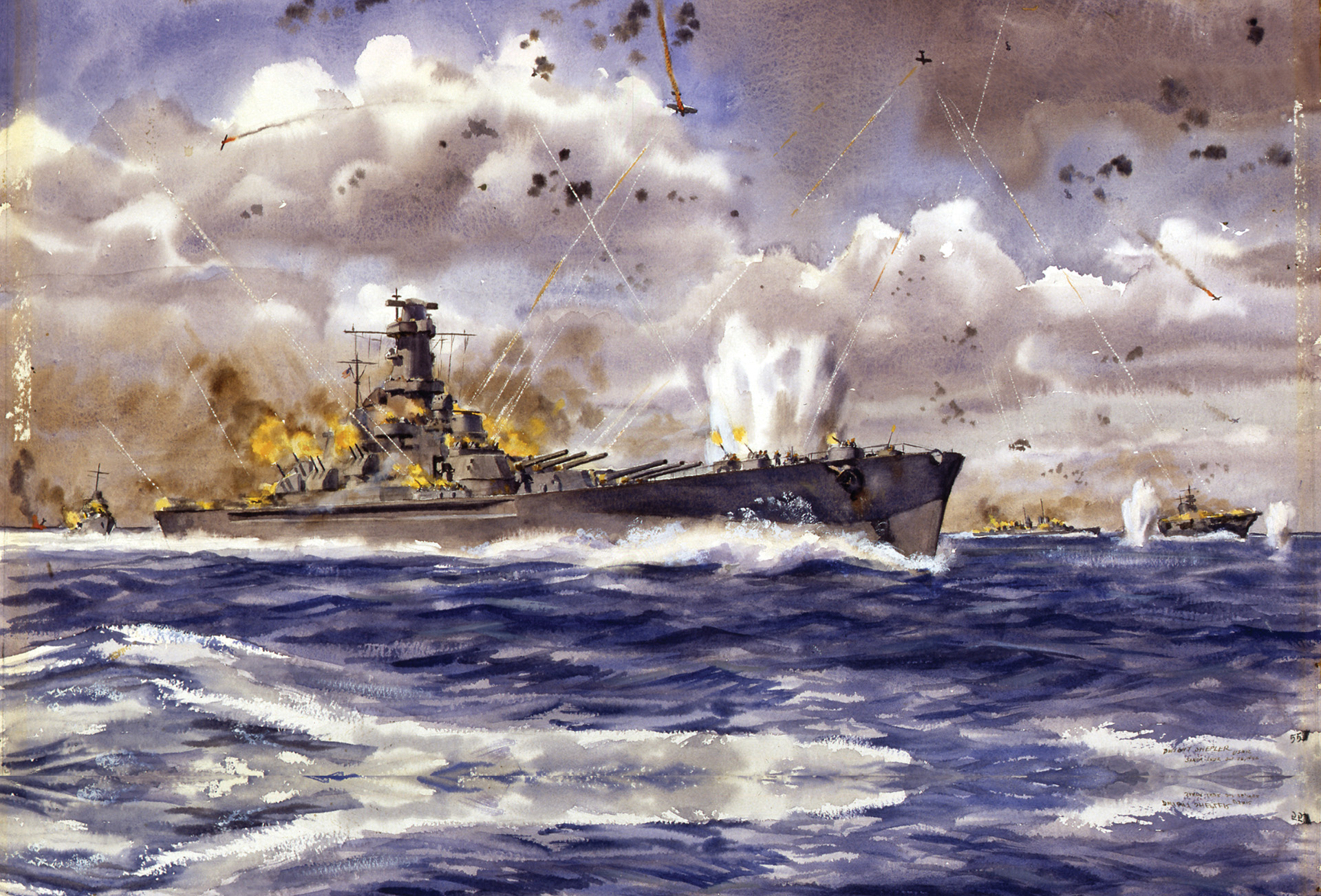

CH: I’ll start by saying that we were bombed by Japanese planes within the first 30 minutes of landing on Corregidor. I was reassigned as a provisional Marine on the South Shore Road. We were susceptible to artillery fire from Cavite and other points on the opposite side of Manila Bay.

We dug foxholes again, and the Japanese attacks intensified after Bataan fell. We were subjected to air attack by both dive-bombers and high-level bombers and artillery barrages by 240mm howitzers on Bataan. We had 3-inch anti-aircraft guns, 5-inch and 8-inch cannon that fired horizontally, and 12-inch rifled cannon and 12-inch mortars in concrete emplacements. Unfortunately, nearly all of the cannon faced seaward, as they were designed to prevent attack from that direction. A landward approach had not been foreseen. The mortars proved to be, by far, the most effective weapon we had against the Japanese, who simply moved most of their artillery back out of the range of the American guns.

JCH: So you faced incessant Japanese shelling?

CH: Yes. I was stationed about 250 yards below Battery Geary, which was composed of 12-inch mortars. On April 29, 1942, in honor of the emperor’s birthday, the Japanese staged a most intensive barrage that started early in the morning and continued most of the day. There was a direct hit on Geary, and a huge column of smoke and dust covered the battery. There was a tremendous shudder above our position. We thought an earthquake had occurred. A Japanese 240mm howitzer shell had scored a direct hit on the magazine of the battery. I had a good buddy named John York who was stationed at the battery. He survived the blast, and he was later dug out by rescuers. Sadly, I found out that John never made it back to the States; I learned from his family after the war that he had died in prison camp.

JCH: So the Japanese were accurate with their artillery shelling?

CH: As far as I was concerned, they were very capable. They would fire shells that were duds, so they would bounce around inside the concrete emplacements and do damage. They would then follow that up with live shells that would hit the damaged areas and explode. We actually found a part of one of the 12-inch mortars from Geary on the South Shore Road where we were bivouacked. The Americans would respond with both counterbattery fire and box barrages, when all batteries would fire at once, with the shells landing in a box pattern. That way the Japanese would not know which battery had fired at what time.

“Along with the Filipino prisoners, we were taken from Corregidor to Manila…”

JCH: Could you describe the final days on Corregidor?

CH: In early May, we were moved from the South Shore Road through Malinta Tunnel to defensive positions on Monkey Point, where Japanese troops were expected to land. The Japanese landed on Corregidor on the night of May 5. My provisional battalion did take significant casualties, including the major commanding it, who was killed. We retreated into Malinta Tunnel amid total chaos. We were ordered to lay down arms on May 6.

I saw my first Japanese soldiers at the mouth of the tunnel, and we were marched in groups to the south end of Malinta Tunnel. Later that same night, the Japanese ordered an artillery barrage on the topside of the island. It was totally unnecessary because there was no organized resistance left; however, the topside defenders had no idea what was happening down below. It was at the mouth of the tunnel that I saw my first horrific act. An American was beheaded by a Japanese officer because the American did not follow an order. It was very unsettling to see his head roll down the slope. We were herded into the 92nd garage area on Monkey Point. There were thousands of us in that area. Sanitation was poor, medical care hard to get, and overall conditions were very dismal. Ironically, burial detail was a sought-after duty because you had a chance to find water and some food.

JCH: So, what did the Japanese do with the American prisoners?

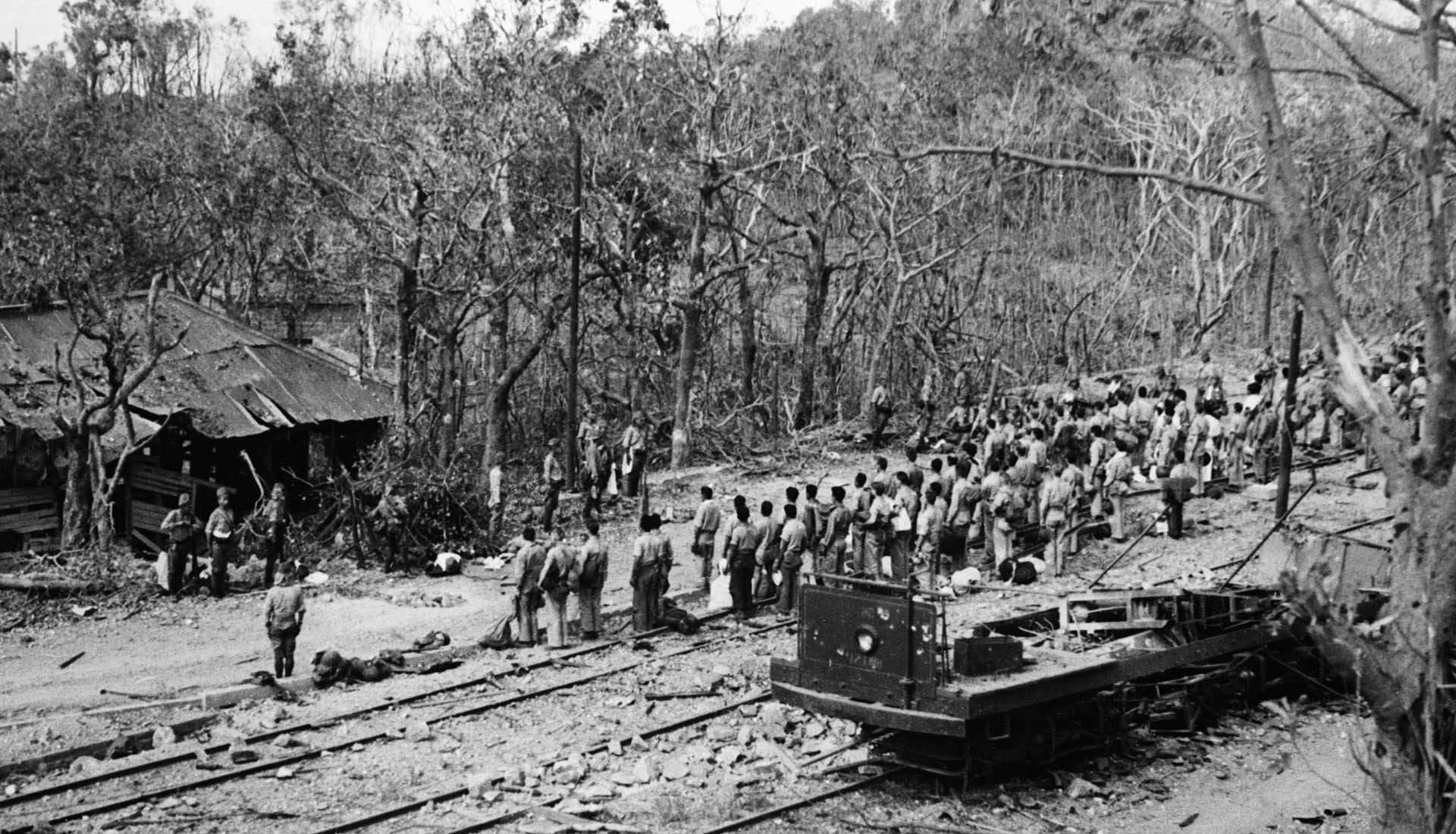

CH: Along with the Filipino prisoners, we were taken from Corregidor to Manila. We were organized into groups and marched in a column along Dewey Boulevard in order to form a victory parade for the Japanese. We went to Bilibid Prison across the Passig River, where we spent two or three days. We were then loaded into boxcars and transported to Cabanatuan, roughly 65 miles away. Air and water were precious commodities during the two- to three-hour train journey. We stayed one night there after being fed and given water; we slept under a school building.

We were then marched out east of town past the No. 1 Camp, where the Bataan survivors were located, to the No. 3 camp. There we were assigned to specific groups, barracks, and work details. We were placed 10 men to a group. If anyone escaped, the Japanese told us they would execute the other men in that group. I can remember that four men escaped one time, but they were recaptured shortly thereafter, and although the four of them were executed in front of the entire camp the rest of their group was spared. I never understood why they tried to escape because there was no place to go.

JCH: How was life at the No. 3 Camp?

CH: Actually, life was not that bad because we [the Corregidor survivors] were generally in good shape. We slept on bamboo slats, and we ate rice as the primary food staple. We had lugaii [wet rice] for breakfast, with water or green tea, and steamed rice for lunch and dinner. There were very few vegetables or fruit and infrequent amounts of bread. Looking back on it, the diet was certainly inadequate by Western standards, and the men who survived were the ones who could tolerate a rice-based diet. We did not receive any Red Cross parcels at this camp. You have to remember that Camp No. 3 was set up to keep the Corregidor prisoners separate from the Bataan survivors because we were generally in much better shape than they were. However, after about eight months Camp No. 3 was closed and we were merged with the Bataan men in Camp No. 1.

JCH: So this change was not welcomed?

CH: No, it was not because conditions at this camp were terrible compared to where we had been. American prisoners were still dying at the rate of several men each day. I am not sure how many total prisoners were in this camp, but I would estimate there were several thousand. Burial detail in particular was very depressing as we worked in four-man litter teams carrying anywhere from four to six bodies at a time. We would dump them in large common graves that held 15 to 20 bodies. I was lucky in that I only caught this detail one time; however, I can remember that even that single instance was very depressing.

“Smiley was the meanest of all the Jap pushers.”

JCH: Speaking of work details, what were your daily activities generally like?

CH: We cleared an area for planting a large garden, and we grew sweet potatoes [comotes], cassava [manioc], taro, and various green plants such as okra and sesame, which the Japs usually took for themselves. We also ate the tender tips of the sweet potato plant. We called this area the farm. It was one of two daily work details, along with “airport” duty. The Japs were building an airstrip for fighters, so we were detailed to dig and move dirt, as well as push wheelbarrows and small train-cars of material. Most able-bodied men worked at one of these two details every day except Sunday. We would work about eight hours a day, not counting walking time to and from the job, and we took our lunch in a “bento box.” It usually was composed of rice mixed with daikon [pickled relish] or vegetables from the farm. The Japs let us run the camp, so our commanding officer, Lt. Col. Beecher, would organize all the details and supervise the camp on a daily basis. Although the Japs could come in our camp at any time, they usually did not unless they had a reason.

JCH: What were the work details like?

CH: Well, you were more likely to get in trouble at the farm than at the airport. There were a different set of guards and pushers [soldiers who acted as administrators who directed the work —they usually only carried a bayonet] at each location and they were a varied lot.

We gave nicknames to each of them based on certain characteristics. For example, Big Speedo was the supervisor in charge of the farm; he was given this nickname because he knew very little English, but he was large for a Japanese at over six feet. All he would ever say to Americans was “speedo, speedo” to finish the task. Overall, he was a generally fair guy. Smiley was the meanest of all the Jap pushers. Although he smiled all the time, he was still a very dangerous person who would beat you for no reason. We learned to stay out of his way.

Air Raid was the head pusher at the airport; he was usually fair, but you had to watch him. Little Speedo was another pusher who was lower ranking than Big Speedo and smaller in size but similar in nature and character to the farm supervisor. Donald Duck was an assistant to Air Raid. He talked constantly, which reminded us of the Disney character. He was unpredictable, and you had to watch him because he would beat you at a whim.

You could be assigned to either work detail, although the majority of the time I worked at the farm. Either job normally consisted of manual labor of some type such as hoeing weeds, planting seeds, and digging or moving dirt. I remember an interesting story that circulated around the camp that helps to illustrate how important the concept of honor is to the Japanese people.

One day Smiley beat an American captain, Arthur Wermuth, for the simple reason that the American was a genuine war hero who was an officer in the Philippine Scouts, and he was well-known for his combat record. Captain Wermuth had done nothing to deserve the beating, but he was so badly beaten by a 2 by 4 that he almost died and he was in the hospital for a long time. Not too long after that Smiley just disappeared. We later found out that Big Speedo had taken Smiley out behind a shed and beaten him severely for an act that he considered to be not honorable. We never saw Smiley again, but we had newfound respect for Big Speedo.

“We landed at the Port of Moji on the island of Kyushu.”

JCH: Were you ever beaten?

CH: No, I was not beaten per se, but I was hit twice, once in the Philippines and once in Japan. Donald Duck took a hoe and swung it in circles and hit me with it a couple of times while we were chopping weeds at the farm. However, I was not hurt. The blows hit me on the back; he was just swinging at anyone in general and I just happened to be nearby.

Later in Japan, I was late in snapping to attention when a Jap guard came into our barracks; he slapped me two or three times on the cheeks to express his displeasure. However, it was my fault because I was not ready when I should have been. I have to say that the basic rule for all American prisoners in the Pacific campaign was to keep your mouth shut and do what you were told. If you did this, normally you were left alone, although there could be exceptions such as Smiley or Donald Duck. All in all, just follow the rules and you would likely do all right.

JCH: Why were you sent from the Philippines to Japan?

CH: Over the 18 months I was at Camp No. 1 several groups of men were transferred to other work locations throughout the Philippines, such as Clark and Nichols Fields, Manila [harbor duty], and Mindanao. One day a group of us was sent to Manila; we spent three or four nights in Bilibid Prison again, [were] issued Japanese uniforms, and then placed in the hold of a Japanese sheep vessel destined for Japan. There were approximately 1,200 men in the hold of this ship. The sheep pens were not big enough to stand in, so we spent most of the time sitting down. We went to Japan via Formosa. Our convoy changed directions and speeds several times in evasive action to escape American submarines and planes.

JCH: How did this evasive action lead to the second of your three charms?

CH: I later found out that my buddy, Jack Tosh, was a prisoner on board a Japanese transport vessel that was sunk by American submarines en route to Japan. You see, the Americans had no idea that these Jap ships were carrying American prisoners; as far as the Americans were concerned these ships were legitimate targets. Jack’s particular ship was sunk with the loss of over 1,000 men. I found out from his parents after the war that he went down with the ship. So, you could say this was my second lucky charm. I was able to make it to Japan without harm. Imagine making it as a POW through a significant period of the war and then dying at the hands of your own countrymen!

JCH: What happened when you arrived in Japan?

CH: We landed at the Port of Moji on the island of Kyushu. We were taken by truck to Camp No. 3 in the Fukuoka Military District near Kokura. This was an old Japanese Army camp, and we stayed in the same facilities as the Japanese soldiers. We slept on bamboo mats in bays, and we were able to bathe once a week in a collective bath area. Again, we had an inadequate diet, with rice as the staple item. However, this time we had different nationalities of prisoners in the camp, including British, Dutch, Indian, and New Zealand troops. The Japanese usually tried to group prisoners together according to nationality. Each of the aforementioned would have their own section of camp.

JCH: What type of work or duties did you do?

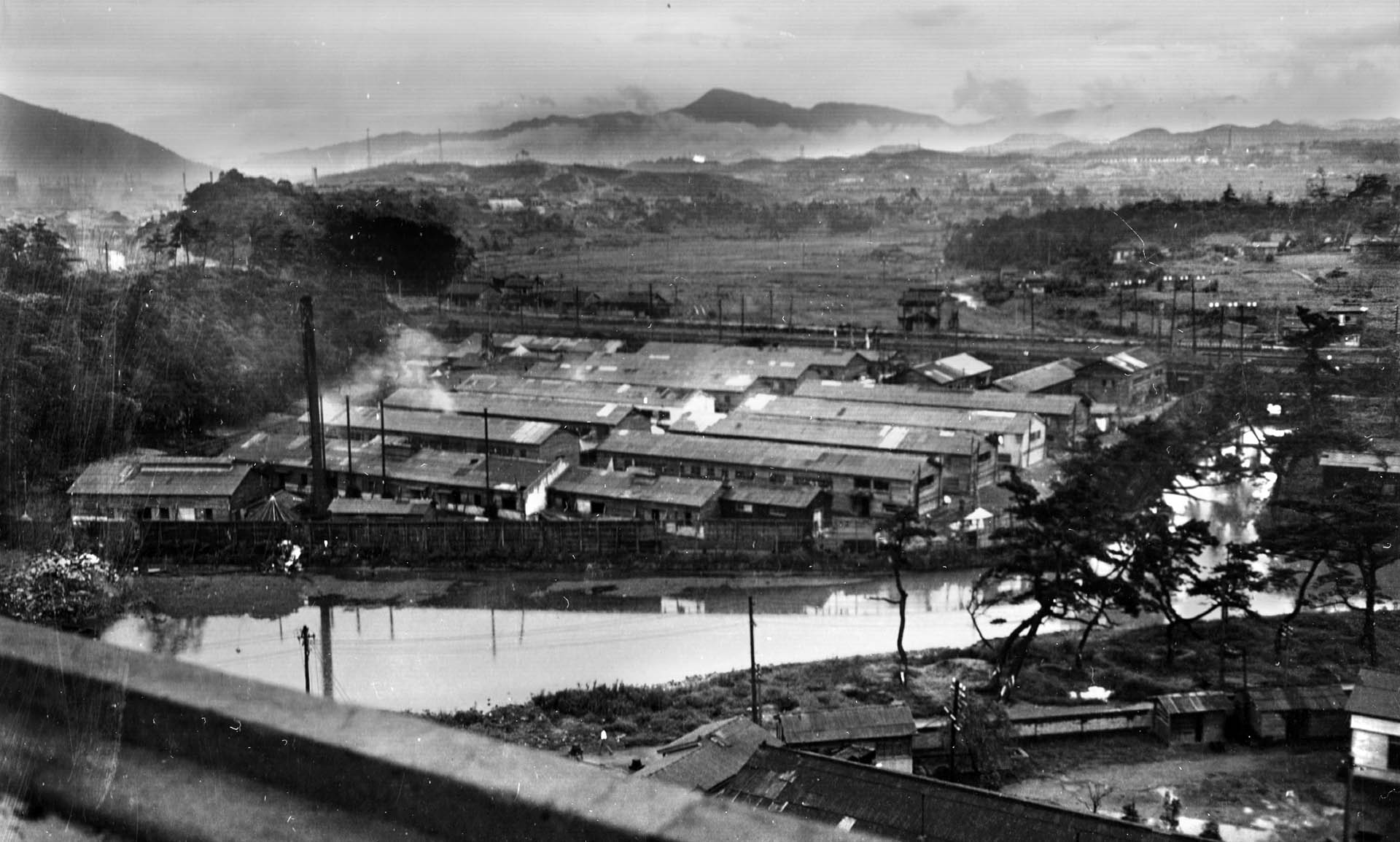

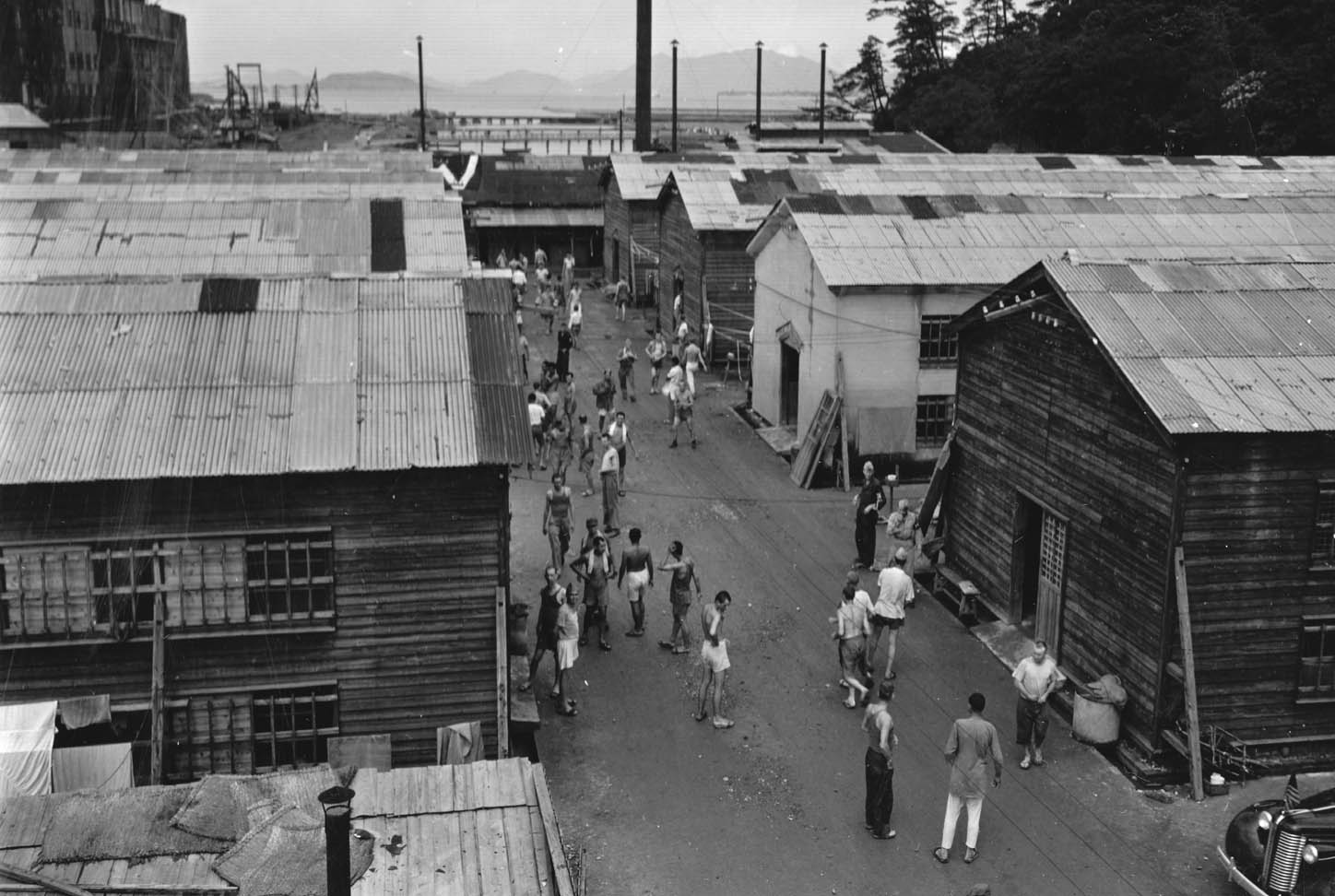

CH: A group of about 200 Americans, including me, worked in the Seitetsu Steel Mill complex near Yawata. This huge facility was composed of several buildings and it was sometimes the called the “Pittsburgh of Japan.” We would ride in open gondola rail cars from camp to a specific site at the mill each day, except Sunday, and we would then walk about a mile or so to the actual building where we worked in various labor capacities. There were soldiers present throughout the process, but the pushers were all civilians. These pushers were the supervisors, and they generally were nice toward the prisoners. I worked for one pusher named Pop, who was an okay guy.

Typical jobs included emptying wet ashes at the bottom of producer gas furnaces. This was very physically hard and dirty work, lining buckets with bricks to keep the liquid steel from melting the container and assisting a Japanese civilian welder. Overall, your work assignments did not vary much. You tended to do the same things over and over again. I worked in one large building where three blast furnaces were located.

I went to work at the mill in July of 1944; it was one month later in August that the plant was spot-bombed by B-29s out of China for the first time. Although the raid lasted an hour, there was little damage, and we went back to work the next day. We were not bombed again until August 1945, when B-24s hit the mill with incendiary bombs. The plant was incapacitated, and we never went back to work. Although we were at work that day, none of us were hurt.

“… we were taken by train to Nagasaki”

JCH: What was your lucky third charm?

CH: After we were repatriated, I found out the primary target for the B-29 carrying the second atomic bomb was the Yawata steel complex. The bomber circled the target for about two hours, but it did not drop the bomb due to cloud cover. Because of fuel constraints, the B-29 moved on to the second target, Nagasaki, in the hopes of finding clearer weather. That city too was covered with the same storm pattern, but at the last minute the bombardier was able to secure visual contact with the target through a hole in the cloud cover. So, the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki instead of Yawata, a good thing for me and the thousand or more other Americans working there. This fact was confirmed by a high-ranking Army Air Corps general, who told us after we were repatriated that the Yawata POWs were the luckiest guys in the world.

JCH: So how did you know the war was coming to a close?

CH: There were more frequent air raids in mid-1945. We started getting interference with our sleep due to being moved to a shelter in the middle of the night. The ending was kind of weird. The Japs just left one night. When we got up the next day, there were no soldiers in the camp. Food was dropped by air. Although we had to be careful, we gorged ourselves on several types of C-rations and chocolates. We stayed at the camp under our own administration. We marked the camp with the letters “P.O.W.” using bed sheets so we could be identified by American pilots. We later found out that plans for repatriation had been made in Okinawa by a team of officers and doctors from each of the POW camps.

JCH: How did the actual liberation process go?

CH: Our Camp No. 3 in the Fukuoka district was liberated by Navy personnel, and we were taken by train to Nagasaki. Although we had heard about the atomic bomb, we saw the damage for the first time as our train went through Nagasaki to the port. The damage was widespread and complete within the bomb’s central radius, although damage lessened as you went away from that point. Triage was done on all the prisoners at the port, and we were then placed on board a British aircraft carrier, which took us to Okinawa. We were given physicals, and then we were taken to Clark Field on Luzon by aircraft. After being placed on board a D-3 cargo plane, we were then taken to Nichols Field. From there we were trucked to a repatriation center east of Manila. We stayed there about 30 days while our service records were reconstructed.

Each person verified his service history, and their medical status was again substantiated. Everyone was promoted one grade except for master sergeants and full colonels. I was promoted to staff sergeant. We were then loaded onto a transport vessel in Manila that took us to Seattle, a journey of about six weeks. I can distinctly remember that there were very few people that met us as the ship steamed into the harbor at Seattle; I was very disappointed because I expected some type of welcoming committee. We were then taken to Madigan Army Hospital at Fort Lewis, Washington. A period of two to three weeks was allotted to allow for residual medical problems. I then went to Brooke Army Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, by train.

“I was the first American POW to return to the campsite and the steel mill…”

JCH: When did you finally make it home?

CH: I was given leave to go home, and I arrived in Breckenridge in November of 1945. I had been gone about five and a half years. My mother knew I was alive because I had transmitted radiogram messages five or six times throughout the course of the war. It was interesting to see that the Japs had censored the messages that my mother had received. I was discharged from the Army in late January or early February of 1946.

JCH: What were your plans then?

CH: I had received the approval from my family to go back to school; the financial situation had improved and my eldest sister told me if I wanted to go to school that I should do so. As it turned out, the GI Bill helped me tremendously, as it did thousands of veterans. I originally wanted to be an accountant, so I enrolled in the Cox Business School at SMU for the spring semester of 1946. After a period of time, I realized that the accounting route was not for me, so I changed to a general biology major with the goal of going to medical school. My grades were good, and I was accepted into Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. I felt pretty good about getting into the school because it was the only one to which I had applied and they only accepted about 60 out of the 300 who had received an interview. It should be noted that I only had 92 semester hours of a pre-med major. I never received a B.S. degree because in those days you could enter medical school without a degree.

JCH: What happened after medical school?

CH: Well, after four years of medical school, I graduated in 1952. I had decided to go back into the Army for security and the status of an officer. Upon graduation and reenlistment, I was commissioned a first lieutenant and I was assigned to Percy Jones Army Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan, for an internship with no specialty area. I started this internship on July 1, 1952. After finishing internship, I completed a six-month program at the Medical Field Service School (MFFS) at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. I then applied for and received a residency in otolaryngology (ENT) at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D.C., from July of 1954 until June of 1957. Additionally, during the summer of 1954, I was promoted to the rank of captain.

My next posting was as chief of ENT at the Valley Forge Army Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, for four years. A two-year tour in the Canal Zone in Panama as chief of ENT at Gorgas Hospital then followed, and I was promoted to major en route to this assignment. A final assignment as assistant chief of ENT at Fitzsimmons Army Hospital in Denver, Colorado, completed my career, and I retired effective December 1, 1964, as a major with 20 years of service.

JCH: Could you describe your return visits to the POW camp in Japan?

CH: Well, I did not hold it against the Japanese troops for the circumstances of the war. The average Japanese soldier was just doing his duty as far as I was concerned. There are good and bad individuals in both the Army and civilian life, and Americans and Japanese are no exceptions. If you want to blame anyone, blame the leaders, not the people. I believed the Japanese people to be fair enough considering the circumstances. For example, rice constituted the basis of their diet, so it was not unreasonable for them to think the same for us.

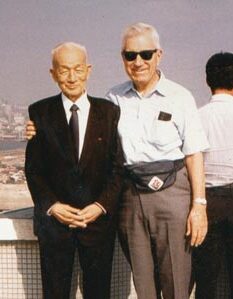

I realize that a good many American soldiers do not feel this way, but it is how I think. With this aforementioned background, I decided it would be interesting to revisit the POW areas in Japan. So my wife and I took two separate trips to Japan in 1987 and 1989. We were assisted by several very nice Japanese individuals who helped us in different ways to find the location of the POW barracks [they had been torn down] and the Yawata steel mill, although the particular building where I had worked had been demolished.

One of these individuals was Lieutenant Colonel Kubo, who was the Japanese officer in charge of POWs in the Fukouka District. He was tried for war crimes by the British in Hong Kong after the war; he was found guilty, and he served eight years in military prison. However, Colonel Kubo was very gracious and helpful during my first visit. He was a true gentleman in all respects. Unfortunately, by the time of our second visit the colonel had died, but his son assisted us on the return trip. I cannot say enough about how polite and gracious these many individuals were in planning and implementing these trips. Indeed, two of them have come to Texas to visit us.

JCH: What else was special about these trips to Japan?

CH: Well, to my knowledge, I was the first American POW to return to the campsite and the steel mill. A Japanese newspaper reporter interviewed me, and articles with pictures were published in the local papers for both of the trips. It’s very interesting to me that the most attention to anything I have done in my life occurred in a foreign newspaper!

JCH: Looking back on your wartime experiences, can you really say three times is a charm?

CH: I guess you could say that, without a little luck in each of those situations, I would not be here today. I’m happy to say it was good luck instead of bad!

Chad Hanna practiced medicine for 40 years, including military time, as well as working in civil service positions for both the federal government and the State of Texas in San Antonio and Temple, Texas. He passed away in 2012.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments