By Arnold Blumberg

The French conquest of Lorraine was nearly complete by March 1634 during the Thirty Years War. The only place of importance still in the hands of Duke Charles of Lorraine, a Hapsburg commander, was the fortress of La Motte, which was encircled by a French army under Marechal La Force. To finally overcome it, La Force tasked a young colonel to lead his infantry regiment in storming a breach in the strongpoint’s defenses.

Attacking uphill into the teeth of enemy musketry and artillery, the young colonel led his soldiers as they fought their way into the center of the fortress. The garrison soon surrendered. The French government was so impressed with the successful assault on La Motte that it promoted 24-year-old Henri de la Tour d’ Auvergne to the rank of marechal- de-camp.

Born in the city of Sedan on September 11, 1611, Henri was the second son of Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne and Duke de Bouillon, a noted soldier and leader of the French Huguenots, and his wife Elizabeth of Nassau, daughter of William the Silent, Prince of Orange. Henri had chestnut brown hair, was of medium height, broad shouldered, short necked, and possessed a high prominent forehead with high cheek bones. He was brought up as a Protestant but converted to Catholicism in 1668. Turenne, as his contemporaries called him, would serve in a number of 17th-century conflicts during the course of his illustrious military career. In addition to the Thirty Years War, Turenne played a prominent role in the Franco-Spanish War, The Fronde, War of Devlution, and the Franco-Dutch War.

Turenne’s military career began when his family sent him to serve in the army of his mother’s brother, Prince Maurice of Nassau, Stadtholder of the Dutch United Provinces. Starting as a common soldier in the prince’s bodyguard, Turenne impressed his uncle to such a degree that he was soon made a captain of infantry at the age of 15. His military service in Holland lasted five years and chiefly involved siege operations. The Dutch bestowed upon him a special commendation for bravery shown during the siege of Bois-le-Duc in 1629.

Turenne left the Netherlands in 1630 and entered the service of France, motivated as much by the desire of his mother to prove the loyalty of her family to the French crown as to secure for her son fur- ther military advancement. By then the Thirty Years War had been raging for 12 years. Although it began as a civil war within the Holy Roman Empire, it took on an inter- national character with the interven- tion of Sweden and France, both of which went to war against the Haps- burg rulers of Spain and Austria.

French Minister of State Cardinal Richelieu promoted 19-year-old Turenne to colonel of an infantry regiment in 1630. Following his courageous performance at La Motte, Richelieu promoted him to marechal-de-camp, the equivalent of major general.

Turenne was stolid and reserved. The most salient feature of his character was his trust- worthiness. A gentlemen soldier, he felt little, if any, personal animosity toward his opponents in warfare. He was unemotional in military matters. His battlefield tactics and campaign strategies were driven by logical calculation rather than fire and dash. Toward his superior officers he was scrupulously obedient, obliging, and good tempered. To his subordinates he never sharply reprimanded them in public, but reserved that for private meetings, and was quick to give an officer who had made a mis- step a second chance. The marshal was considerate and kind toward the rank and file.

France intervened directly in the Thirty Years War in 1635. Turenne participated in the Lorraine and Rhine campaign under Louis de Nogaret, Cardinal de la Valette. After raising the siege of Mainz, the French and their allies had to fall back after their supply lines were cut by the enemy. During a disastrous retreat marked by great privation suffered by the allied forces, Turenne did yeoman service conducting a series of rearguard actions that saved the army from dissolution. During this episode the general not only showed great personal courage and an understanding of the need for proper army logistical management, but also a sincere regard for the welfare of his men.

Turenne was wounded in the right arm dur- ing the storming of Saverne in 1636. He was then given his first independent command with orders to drive an Imperialist army out of Hapsburg-controlled Franche-Comte, which he achieved rapidly and with few losses. The fol- lowing year he took part in the Flanders campaign. Although that year’s fighting proved indecisive, Turenne, who by then was a lieutenant general, again proved himself to be a competentcommander. In 1638 he was instrumental in taking the key fortress of Breisach on the right bank of the Rhine River. The capture of Breisach safeguarded French control of Alsace and Burgundy.

Sent to Italy by his patron, Richelieu, Turenne took part in the continuing Franco-Spanish War, serving under Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt. Turenne performed ably in the complicated siege operations that enabled the French to capture Turin on September 20, 1640.

Afterward, he helped capture the Piedmontese cities of Cuneo, Ceva, and Mondovi in 1641. The following year he served as second in command of the French forces that con- quered Roussillon in Catalonia.

France bestowed the rank of Marshal of France on 32-year-old Turenne on December 19, 1643. His first orders were to reorganize French forces on the upper Rhine in the aftermath of the embarrassing defeat of French forces at Tuttlingen in Swabia on November 24-25, 1643, at the hands of General Franz von Mercy’s Bavarian army.

In the spring of 1644, Turenne crossed the Rhine at Breisach and defeated an Imperialist force near the source of the Danube River and Black Forest. He joined forces with Louis de Bourbon, Duke of Enghien, known as the Great Condé, and with a force of 19,000 men the two French commanders defeated Mercy’s Bavar- ian army at Freiburg in August 1644. Although Condé was in charge of the French forces because he was a royal prince, it was Turenne’s tactical abilities that compelled Mercy to retreat east from Freiburg.

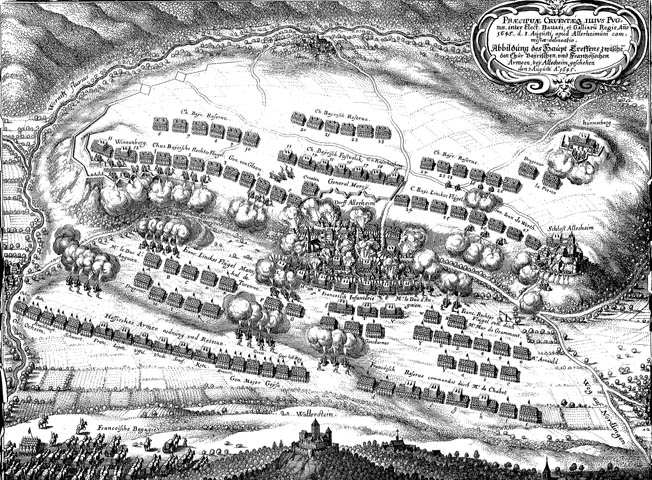

The fighting between Turenne and Mercy went back and forth across southern Germany. In March 1645, Turenne again crossed the Rhine with 11,000 troops and attacked Mercy south of Wurzburg. On May 2, Mercy counterattacked Turenne, whose forces were dispersed at the time, at Marienthal, defeating his opponent and forcing Turenne to retreat to the Rhine River. Then, Condé and Turenne led an army of 15,000 French troops into Swabia and defeated Mercy’s 12,000 Bavarians at the Second Battle of Nordlingen on August 3, 1645.

Although Condé was in overall command, the victory was Turenne’s alone. With the French right and center defeated, it was Turenne’s furious cavalry charge against the Bavarian right flank that sent Mercy’s troops fleeing from the battlefield. But a reinforced Imperialist army drove the French back to the Rhine. Time was on France’s side, though. The Thirty Years War entered its final stage, and both Bavaria and Austria would soon be forced to capitulate.

In 1646 a Franco-Swedish army co-commanded by Turenne and Carl Gustaf Wrangel conducted a series of strategic marches in which they advanced from Freiburg to the gates of Munich, capturing several key fortresses along the way. Bavaria signed the Truce of Ulm with France and Sweden on March 14, 1647. In the autumn of 1647 Bavaria broke the truce to assist Austria in its struggle with France and Sweden. This afforded Turenne another opportunity to fight the Imperialists. He led a Franco-Swedish army to victory against the Imperialist forces in the last battle of the Thirty Years War fought at Zusmarshausen on May 17, 1648.

During the protracted Thirty Years War, Turenne had led French forces to victory multiple times. In the aftermath of the conflict, he came to be regarded as the leading French commander in the Thirty Years War.

Turenne next served as a commander during The Fronde, a French civil war that lasted for five years from 1648 to 1653. At first, Turenne sided with the anti-royalist party, but by 1651 he had switched sides and was leading royalist armies against the Frondeurs and their Spanish allies. Turenne defeated Condé’s rebel army at the Battle of Faubourg St. Antoine on July 2, 1652, and occupied Paris in the aftermath. From 1653 to 1658, he repeatedly defeated Spanish armies on both France’s eastern and southern borders. His greatest achievement during that period was leading an Anglo- French force to victory over a Spanish-Royal- ist army at the Battle of the Dunes fought on June 14, 1658.

After King Louis XIV took personal control of the French government on April 4, 1660, the French king rewarded Turenne for his many past services to the crown by elevating him to Marshal-General of the Camps and Armies of the King. This honor gave the recipient the authority to control all the land forces of France at a time when a marshal only commanded a single army and gave him greater control over the organization and training of the French armies.

Turenne played a prominent role in the War of Devolution from 1667 to 1668, in which Louis XIV’s armies conquered the Hapsburg- controlled Spanish Netherlands and the Franche-Comte. Unfortunately for the French king, the subsequent Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle compelled the French to return Franche-Comte to Spain; however, the French managed to retain a small part of Flanders.

In 1670, King Louis XIV enlisted Turenne to negotiate the Treaty of Dover with England. The treaty required England to aid France in its war of conquest against the Dutch Republic. In the wake of the treaty, King Louis began planning his invasion of Holland. Louis’s plan called for both Turenne and Condé to have leading roles in the enterprise, although not operating near each other. Louis planned to establish separate commands for other marshals, which would be supervised when necessary by either the king or Turenne.

During many of his military operations Turenne led armies inferior in size to those of his opponents, but this situation was reversed during the Franco-Dutch War of 1672 to 1678. Against a Dutch field army numbering merely 25,000, with another 12,000 garrisoning the vital Meuse River fortress of Maestricht, and 6,000 Spanish allies, Louis had an active army of 100,000, with an additional 30,000 men provided by several German allies. Turenne commanded the majority of the French forces.

Turenne planned the initial stages of the attack on Holland, including the taking of Maestricht with limited forces, while marching to the Rhine River and capturing many towns and enemy strongpoints along the way. However, once the French entered the United Provinces the main Dutch army would have to be faced. Condé’s men were soon placed under Turenne as the French advanced on Amsterdam, burning and pillaging the entire way. In response to the French juggernaut, the Dutch flooded Brabant, Holland, and Dutch Flanders.

Widespread flooding precluded military operations, so the two sides attempted to negotiate a peace treaty. But the Dutch deemed the French terms too harsh and rejected them. Turenne had counseled more lenient conditions, but Louis XIV would not hear of it.

Fearing the growing power of France, the major European powers began to unite against her. In 1672 Austrian and Brandenburg forces converged on the Rhine River to join forces with the Dutch. Turenne blocked repeated attempts by these forces to cross the Rhine. Although this involved little fighting, it did require frequent marches. In 1673, he drove the Austrians and Brandenburgers out of Westphalia and advanced on Frankfurt. This compelled Frederick William, the Elector of Brandenburg, to abandon his alliance with the Dutch.

Turenne, with only 20,000 men, was facing 40,000 soldiers of an Austrian-Saxon coalition supported by several minor German states commanded by Italian Raimondo Montecuccoli. Montecuccoli marched to rendezvous with the Dutch on the Lower Rhine. Turenne moved to block the junction of their armies. Giving the Frenchman the slip, the Italians joined the Dutch at Bonn. This one masterful stroke forced the French from Holland. Turenne then went into winter quarters in Alsace and Lorraine.

The campaign of 1674 witnessed a broad coalition that included practically all of the major European powers fighting the French. As a result, Louis abandoned all the territory he had taken on the Rhine and Meuse in the previous two military operations. Turenne was tasked with safeguarding the Rhine front with an army of only 15,000 men. In this operation Turenne demonstrated more than in any other campaigns of the wars of Louis XIV that maneuver could be an effective means of defense. During June he crossed the Rhine and with only 9,000 men defeated an Imperialist force at the Battle of Sinzheim on June 16. Turenne, sword in hand, led a number of cavalry charges himself. However, in August a reinforced Imperialist army took Strasbourg, giving France’s foes access to Alsace.

Determined to beat back the Austrians before they were reinforced by an advancing Brandenburg-Prussian army, Turenne attacked Field Marshal Alexander von Bournonville’s Imperialist army near Entzheim on October 4, but only achieved a draw. Both sides withdrew after suffering upward of 3,000 casualties. Turenne continued his efforts to liberate Alsace by conducting a surprise march in the winter in a time when armies campaigned from spring to fall and remained static during the winter. The famous effort became known as Turenne’s Winter Campaign.

Turenne led his army southward from Saverne in northern Alsace in early December using the Vosges Mountains to screen its movement. The Imperialists were garrisoned for the winter in bivouacs on the left bank of the Rhine River from Strasbourg to Mulhouse. Aware that spies were operating in the region, Turenne divided his army into small units sending them over snow-covered mountains. The French units regrouped at Belfort. Turrene and Bournonville clashed at Mulhouse on December 29. Turenne defeated the Imperialists, forcing them to withdraw northward.

Turenne then advanced on Colmar, where a fresh army under the Elector of Brandenburg gave battle at Turckheim. Turenne launched an aggressive assault with his 30,000 hungry and footsore troops. After feinting to the center and right, Turenne struck Frederick William’s left, forcing him off the field. Although Turenne did not follow up his victory at Turckheim with a vigorous pursuit of his opponent, it took away nothing from Turenne’s brilliantly conceived and executed Winter Campaign.

The war continued in 1675 in Germany with Montecuccoli facing off once more against Turenne. From June to late July, the Imperialists maneuvered to gain entry to Alsace, while the French marched to prevent that occurrence. On July 22, Turenne began a turning movement with his 25,000 men to pin his antagonist against the Rhine before the latter could cross into Alsace. Alerted to the looming danger, Montecuccoli withdrew his army to the east and the mountains. Turenne chased the retreating foe and forced him to halt and confront him at the town of Sasbach on July 27.

As the two armies readied for battle, Turenne and his chief of artillery, Saint Hilaire, reconnoitered an enemy artillery battery sited on the French right. Perhaps because the red cloak worn by Saint-Hilaire caught the attention of the gunners, they fired at Turenne’s party. The result was that a cannon ball tore off Saint- Hilaire’s arm and struck Turenne in the upper body, killing him. “Today died a man who did honor to mankind,” said Montecuccoli upon learning of Turenne’s death.

Turenne’s death compromised the French campaign, and the French army fell back in good order on July 29. Montecuccoli pressed the French and fought a bitter battle with them at the Schutter River. With Turenne gone there was no doubt the French would abandon the Rhine region and retire to Alsace. Condé assumed command of the forces, and it was only with great difficulty that they were able to hold Alsace for the rest of the year.

After Turenne’s death, King Louis XIV insisted that Turenne’s body be interred in the Abbey of Saint Denis, burial place of the French kings. Napoleon Bonaparte later had the remains removed to Les Invalides in Paris, where they remain to this day.

Turenne showed great tactical brilliance over his long career; however, in the realm of strategy he was cautious. Great maneuvers such as his Winter Campaign of 1674-1675 were his stock and trade. Furthermore, he always strived to keep his army well supplied, and he looked closely after his troops’ well-being. Turenne was arguably the most talented French general to serve Louis XIV. Napoleon regarded Turenne as one of history’s greatest commanders, and for that reason he instructed all of his officers to study Turenne’s campaigns.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments