By Kevin Mahoney

The infantryman’s war in Korea was fought with a number of World War II vintage weapons and items of personal equipment, including the steel helmet. Designated the M1, it was a unique design when it appeared in 1941 as a replacement for the M1917 “Doughboy” helmet that had been in use since World War I. A departure from earlier designs, it had two components: a steel shell and a separate liner worn inside it.

The shell was initially produced with steel loops (or bales) welded to the steel shell to hold the web chin strap. In late 1943, however, these loops, prone to fracture, were replaced by hinged loops. It is this later style that is encountered on Korean War-period steel helmets.

The liner worn inside the steel shell was produced initially in fiber and later, in much larger numbers, in plastic during WWII. The latter type was issued to troops during the Korean War. The liner contained an internal suspension made of web material riveted inside it. A headband was attached to this suspension, first by snaps and later by clips, as was a neckband. The last feature was a leather chin strap, attached to posts inside the liner.

The minutia of liner variations is too extensive to cover here, but one can expect to find two types of interior webbing in liners used during the Korean War. As the U.S. military often issued equipment years after it was no longer manufactured, WWII-vintage liners with khaki webbing were used in Korea. Green webbing (called “Olive Drab No. 7” or “OD 7,” authorized for use in 1943) is found in liners manufactured after World War II.

A variation of the standard liner described above was worn by the 187th Regimental Combat Team, the only airborne unit to serve in Korea, during their two combat jumps in late 1950 and early 1951. This liner has inverted “A” webbing to hold the chin strap. It was worn with the standard issue M1 steel helmet with hinged chin strap loops, mentioned earlier.

The M1 steel shell underwent a modification at the end of World War II that saw increasing use during the Korean War. Although the WWII sewn chin strap, in either khaki or “OD 7,” was used on helmets with swivel loops, the T-1 chin strap developed at the end of the war had begun to come into use in Korea. The T-1 utilized a ball joint attached to the buckle that would come apart under more than 15 pounds of pressure, and offered the added advantage of attaching to the shell loops with metal clips.

The change to the T-1 strap was made for several reasons. Reports from the front during World War II revealed that concussion from an explosion could severely jerk a helmet secured by a chin strap on the wearer’s head, sometimes causing serious injury. The new buckle on the T-1 strap would separate with only a few pounds of force, thus preventing such injuries. The steel clamps allowed for easier replacement of broken straps in the field because the earlier sewn strap required a sewing machine for replacement.

These chin straps, regardless of the type, were usually worn in a manner unforeseen by the designers. Rather than being tucked under the chin as intended, the majority of soldiers and Marines wore the leather liner strap over the helmet’s brim and the canvas strap around the back of the helmet. Both helped to keep the liner and helmet together during strenuous activity. The fashion of wearing both straps in this manner became an enduring image of the GI in combat in the mid 20th century.

This image was enhanced when unit insignia were painted on helmets, a practice begun in World War I and continued through World War II into Korea. The helmets used by the army in Korea could sport such unit insignia, usually of a division, regiment or battalion, although by no means did all GIs do so. Such insignia certainly didn’t enhance the camouflage provided by the flat, olive-drab paint found on the M1 but could serve to embody a soldier’s pride in his unit.

The 1st Cavalry Division helmet sported such emblems with the divisional insignia painted on both sides, a fashion that appears to have been followed by most army divisions in Korea. It is small wonder that the 1st Cavalry’s insignia was worn on their helmets; Korean veterans have remarked that the 1st Cavalry’s presence in an area was generally made known by the prominent display of their yellow shield on signs wherever the division went.

The Marines, however, didn’t go in for such insignia as they generally continued to use the herringbone twill camouflage helmet cover introduced during World War II. The first Marines in Korea in the summer of 1950, however, members of the Provisional Marine Brigade, are often seen in photos without helmet covers, although the shortage was soon remedied. This cover was reversible with green camouflage on one side, tan on the other. A later pattern, developed during World War II, had slits in the fabric for insertion of branches that the initial issue lacked. Both were used during the Korean War but the Marine Corps emblem, often seen stenciled on the herringbone twill field cap of the period, does not appear to have been used much, if at all, on the camouflage helmet cover.

Army troops also used covers, although less elaborate than those of the Marines. The ad-vantage gained by their use was a reduction in the heat of the sun beating directly upon the steel shell, much as a canopy placed on the roof of a house reduces the temperature inside. An olive-drab cotton cover, apparently produced locally in the Far East since no quartermaster specification has yet come to light, was used by both Army and ROK troops during the war, although it does not appear to have been general issue. The limited availability of these cotton covers, however, was not a major impediment for the resourceful GIs who fashioned their own covers.

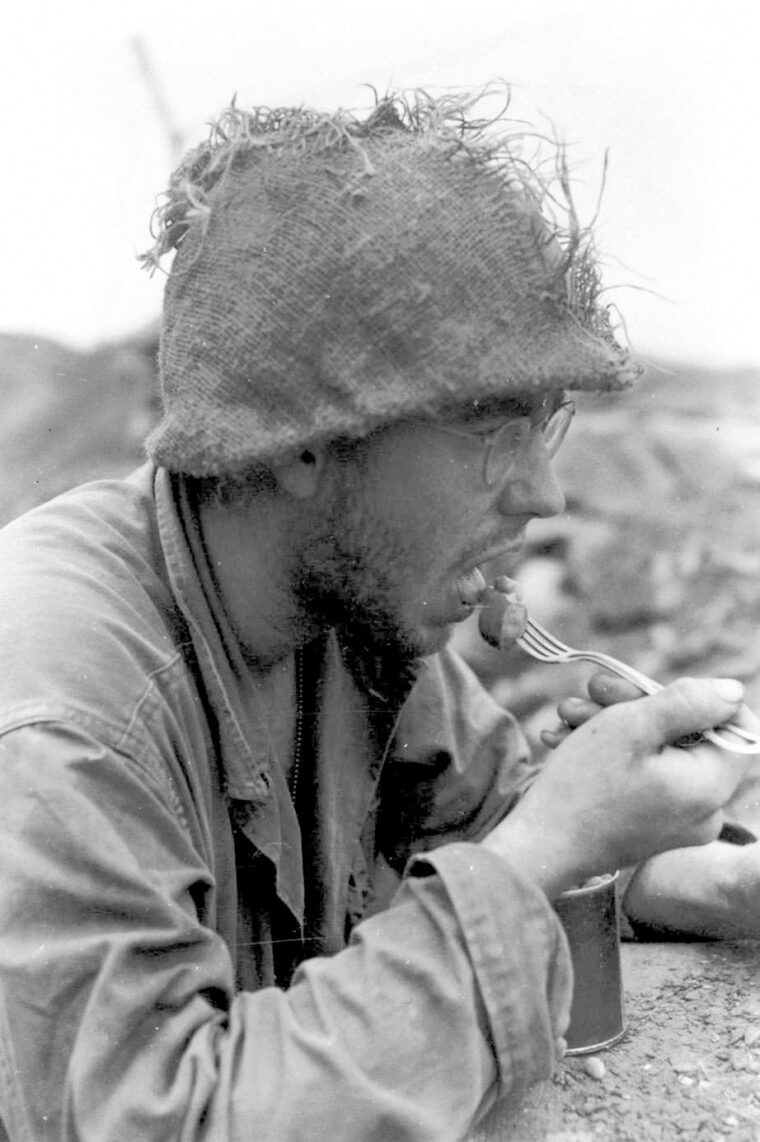

Such covers, often seen on Korean War helmets during the last two years of the war, were made from the burlap used for sandbags. With the advent of positional, trench warfare after the summer of 1951, sandbags became a prominent feature of the defensive positions of U.S. and U.N. troops. The millions of bags needed to reinforce these positions provided material immediately at hand for use as an effective helmet cover.

One helmet with a burlap cover, illustrated here (below left), provides a glimpse of the fighting in Korea and the effectiveness of the steel helmet in protecting its wearer. This helmet is a late WWII production M1 with flexible chin strap loops and sewn khaki chin strap, worn by a GI of the U.S. 45th Division. As a member of the 180th Infantry Regiment division, one of the two National Guard divisions that served in Korea, he saw action on the front line during late 1952 and early 1953.

Late in March 1953, the 180th was holding the line against North Korean forces on the eastern end of the front that spanned the Korean Peninsula. The early morning routine of patrols returning from the No Man’s Land between the lines was followed by the usual desultory shelling by North Korean artillery and mortars. In mid-morning a mortar round landed in an American trench and wounded two GIs, including the wearer of this helmet. A fragment penetrated the steel shell and liner but fortunately only inflicted a scalp wound. Although other wounds brought about his evacuation to the United States, the helmet most certainly saved his life.

A helmet like this example with a verifiable story to go with it, as well as those with unit insignia painted on them, are certainly the most sought after for the collector. Either confirms that a helmet was actually used in combat in Korea, rather than being one of the millions of anonymous helmets that could have been used in combat. Their value can range to over one hundred dollars. A standard Korean-era steel shell, on the other hand, with a liner of the same vintage, could be purchased for as little as $20.00.

The days of purchasing M1 steel helmets in surplus stores seem to be gone forever, but they can still turn up at estate sales, yard sales and flea markets because many GIs took their helmet home with them upon discharge. Internet auctions are another place where one can find helmets regularly offered for sale, often with good photos to help the potential buyer determine the exact vintage of a helmet from the comfort of home. Militaria shows are still a good purchasing venue as well and usually offer the collector the opportunity to examine several helmets. There is still no substitute for a hands-on inspection of a helmet before a purchase. But regardless of the circumstances, in buying an M1 helmet a collector is purchasing one of the enduring symbols of Americans in combat during the 20th century.

Join The Conversation

Comments