By Ted Pulliam

On June 15, 1930, a poised cadet from the Virginia Military Institute proudly drove his dilapidated old Ford through the gates of Fort Myer, Va., across the Potomac River from Washington, DC, and home of the crack 3rd Cavalry Regiment.

A dozen years after World War I ended, Cadet Charlie Dayhuff and other Reserve Officer Training Corps cadets were beginning six weeks of concentrated training given to men who wanted to be officers in the modern U.S. Cavalry. Cadet Dayhuff was about to trade his car for a horse.

At the same time, the U.S. military at the highest levels was debating whether to trade its horses for cars—or for some form of mechanized vehicle. The horse cavalry had survived World War I and the 1920s. But by 1930, the debate over horse or machine had begun in earnest and would not conclude until after World War II had started.

The “Sheep-Like Rush” to Mechanization

The story of the horse cavalry between the wars involves well-known figures like John J. Pershing, George C. Marshall, and George S. Patton, Jr. (the latter’s views may be surprising), and some lesser known, like Generals Adna R. Chaffee and John K. Herr. It also involves men in much lower ranks, like Cadet Dayhuff and his fellow ROTC cadets, who were trained to fight the next war on horseback.

In the end, the cavalry lost its horses, but not until its supporters made a determined fight against the “sheep-like rush to mechanization,” until Cadet Dayhuff and his friends experienced what it was like to be a cavalryman, and not until, on December 22, 1941, the U.S. horse cavalry actually met tanks in combat.

But first, the earlier war. A little after 4 o’clock on the afternoon of September 12, 1918, three hastily assembled troops of roughly 300 horsemen of the U.S. 2nd Cavalry rode their mounts into a heavy wood in northern France. The cavalrymen were part of the attack on the St. Mihiel salient that had begun at dawn that day. Up to now, they had spent most of their time in France running remount depots for the medical corps, the artillery, and the transportation service, all of which used horses to haul equipment. Now well behind the original German lines, they were riding ahead of their infantry for the first time. This was the U.S. Cavalry’s first chance for actual combat in World War I.

The cavalrymen rode through the forest in two columns, one on each side of a central road. Halfway through the woods, they suddenly confronted the most effective weapon of the war, the machine gun.

The First and Last Defeat

Fire came at them from the right front, at least one machine gun and possibly several automatic rifles, but the trees were too thick to see for sure. Their commander quickly ordered the troopers to turn back down the road to dismount and then advance again. “The men were falling back … in good order, when suddenly [another] machine gun opened up on the column from a small trail leading from the main road on the right,” wrote Captain Ernest N. Harmon, who was there. “The Germans had allowed our patrols to go by and had brought their guns to the edge of the woods as the column started back.”

Their horses were culls from veterinary hospitals and remount depots—most completely new to working as cavalry mounts. This second machine gun proved too much. The inexperienced horses bolted down the road carrying their riders with them. Then another machine gun opened up from a trail on their left. In the confusion, few troopers could check their horses. They burst from the same woods they had just entered and scattered out over a field. Finally the cavalrymen regained control. Slowly, they rode back to their own lines.

Not only was this defeat the first combat experienced by the U.S. Cavalry in the war, it also was its last, at least by a force of any size. It was not an enviable record to carry into the peace that followed.

Immediately after the war, General John J. Pershing, leader of the American Expeditionary Force, appointed a board of officers to recommend a new army structure. The board focused on creating chiefs for various branches—infantry, artillery, signal corps, and so on under a single chief of staff. The infantry clearly had contributed heavily to the victory and merited a separate branch chief. The air service was new but had proven its value. Tanks had some successes and some problems. What about the cavalry?

The Case for Cavalry vs Tanks?

Cavalrymen pointed out several things: First, the war on the Western Front had been unique: It was a war without movement. The two sides simply faced each other and slugged it out for four years. No war had been fought like it before, and its great cost, huge number of casualties, and indecisiveness would ensure that no nation would ever fight that way again.

They argued that the cavalry’s strength was its mobility. The usual battle progressed in three phases: First, two forces sought to locate each other; second, the forces struggled for dominance; and third, one side was defeated and the other pursued.

Cavalry was most valuable when war was fluid—during a battle’s first (locating) and third (pursuit) phases. On the Western Front, the first and third phases had been brief. But the middle phase (struggle) had lasted four long years.

Cavalry was important in the middle phase also, the cavalrymen argued, but mainly on the flanks of a battle. On the Western Front, however, there had been no flanks. The west end of the line of trenches stretching across Europe rested on the sea and the east end on neutral Switzerland and the mountains. This situation would not recur either.

Future wars would be wars of movement, when cavalry would be essential. Tanks had some success in the war, but they were slow. Neither the light tanks used by the United States (Renaults borrowed from the French) nor the heavy tanks (borrowed from the English) could move more than five or six miles per hour, even on a good road.

Off road, tanks were even more deficient. The day the first Renaults were used by the Americans (during the St. Mihiel offensive), only one tank was lost to enemy fire, but 22 were lost to “ditching” (getting stuck in shell craters or trenches) and 21 to mechanical failure. Of the 142 tanks operated by Americans on the first day of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, only 16 were available for the last assault a week later—again largely due to ditching and mechanical failure, according to David E. Johnson in his book Fast Tanks and Heavy Bombers.

Also, tanks ran out of gas and could be refueled only when road-bound motorized vehicles could reach them. Moreover, tanks were deaf and blind. A soldier buttoned up in a World War I tank had no radio. To communicate with other tanks or with infantry, he had to open up and wave a signal flag. Of greater concern was that his vision was so impaired “that enemy gun crews usually found the tank before the tank found them,” as J.L.S. Daley related in “From Theory to Practice: Tanks, Doctrine, and the U.S. Army.”

Airplanes, cavalrymen asserted, were useful for long-range reconnaissance—if it was daylight and the weather was good. Airplane-to-ground communication generally was too poor for planes to be useful for short-range reconnaissance. They might be of some use supporting infantry and cavalry in the attack, but they could not take prisoners or occupy ground.

The all-weather, all-terrain, live-off-the-ground, fast, mobile horse cavalry was the force required.

U.S. Cavalry Continues After the Great War

Cavalrymen pointed to British successes during the war with horse cavalry in Palestine. The Dorset Yeomanry successfully charged Turks on a ridge near Jerusalem on November 13, 1917, reported an article in The Cavalry Journal published in 1920. The Yeomanry rode across 4,000 yards of open plain, then 150 feet up a hill—all under heavy artillery, machine gun, and rifle fire—overran the position, and captured 1,096 prisoners, two field guns, and 14 machine guns. Their losses were 129 cavalrymen killed and wounded and 150 horses.

“The weapon used was the sword,” the article stated. It quoted a captured Turkish officer about the charge: “We were amazed and alarmed, because we could not believe our eyes. We had been taught that such a thing was impossible … yet now we saw this very thing being done. We did not know what to do.”

Cavalrymen were quick to point out that the terrain in Palestine was much like that along the U.S. border with Mexico; and during World War I, the U.S. Cavalry had fought bandits in Mexico in 1916 before Americans fought Germans in Europe in 1917.

Just after the war, the cavalrymen had little opposition. Other branches were more concerned about preserving their own turf than attacking another’s. In addition, Pershing’s board needed little convincing. It was composed of high-ranking officers who had little front-line experience of the Great War—their positions were too senior and the U.S. experience in France had been too short. They looked to the past, where there had always been cavalry. To almost no one’s surprise, the board recommended that Congress include cavalry in new legislation as one of the combat arms.

If that was not sufficient for Congress, Pershing, who had led cavalry into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa in 1916, intervened. He wrote, just before final Congressional action: “[T]o some unthinking persons the day of the cavalry seems to have passed. Nothing could be farther from the truth. The splendid work of the [British and French] cavalry in the [first] few weeks of the war more than justified its existence and the expense of its upkeep in the years of peace preceding the war.…”

That was enough for Congress. The National Defense Act of 1920 created a separate chief for the cavalry as well as the other combat arms. Moreover, that same Act placed the tank corps, which had been a separate branch during the war, firmly under the control of the infantry.

The implications of this new army organization did not escape the attention of one army officer. Major George S. Patton, Jr., a former cavalryman, had formed and led the first U.S. tank unit into combat during the war. He realized, however, that a tank element subordinate to a much larger infantry branch offered little hope of personal advancement. He switched back to the cavalry and soon became one of its principal spokesmen. “In offensive and defensive actions in stabilized situations, as well as in warfare of movement,” he wrote in The Cavalry Journal, which was the semiofficial publication of the U.S. Cavalry, “modern Cavalry has proven its value.”

The cavalry had survived. For a while at least, the horse was safe. And if the cavalry was to help fight the nation’s future battles, it needed a reserve of trained officers.

The Stables at Fort Myer

So at Fort Myer one June morning in 1930, Cadet Dayhuff and 47 other ROTC trainees (from VMI, Culver Military Academy, and Dartmouth) marched down to the stables in their olive-green uniforms, wide-brimmed campaign hats, and knee-high leather riding boots to choose their most important item of equipment for the next six weeks: their horses.

The stables were long, low buildings of red brick from which emanated the musty odor of horses and straw. Between the stables the horses stood quietly in a dusty corral, their bridles hitched to a long rope running between tall posts known as a picket line.

Dayhuff’s father was a cavalry officer with the 4th Cavalry at Fort Meade, SD, and the junior Dayhuff knew horses. He chose a bay, while a friend, Louie Roberts, whose Norfolk, Va., background gave him no similar experience, selected a small, black horse. Roberts reasoned, “Small, so less horse to groom.” But Dayhuff knew a bay horse sweats less than a black one and requires less grooming. Before long, Roberts knew it too.

Some trainees had learned at school not to pick a “herring-gutted” horse either. The body of such a horse angled back and up sharply from its chest to its rear legs. A saddle cinched around this body soon worked backwards and loosened. When a rider leaned too much on the right stirrup or on the left, he could suddenly find himself and saddle underneath the horse.

Another VMI cadet, Eddie Pulliam, son of a commonwealth attorney from Richmond, Va., selected a beautiful big horse and found out too late it had only one good eye. “Try to jump a one-eyed horse,” he said years later. “The first time he approached a jump, he looked at it real hard with one eye, then the other—and then went around on the side.”

A Focus on Rapid Advance

The cadets learned later that their horses were normally assigned to the headquarters band and were not great cavalry mounts even with two good eyes. One cadet claimed his bulky horse surely carried a baby-grand piano, while another said his horse would not have carried a piccolo.

Once a cavalryman had his horse, what was he to do with it? Scout to find the enemy, screen friendly troop movements, delay an enemy’s advance by darting thrusts and quick withdrawals, pursue the enemy after a breakthrough, maintain liaison with other units, and seize enemy positions—all traditional cavalry roles.

Cavalry theory, set forth in Employment of Cavalry published in 1924 by the Cavalry School in Fort Riley, Kan., acknowledged that at times machine guns, artillery, and tanks were useful—they could pin the enemy to the ground so that the cavalry could take the offensive on the flanks.

Mainly, however, the Cavalry School stressed the cavalry’s ability to take care of itself in a fight and to advance rapidly. A cavalryman could ride to a fight and then dismount, but he should strive to fight mounted. When dismounted, the cavalry’s fighting force was reduced because some troopers needed to stay with the riderless horses. In the 1920s, the cavalry boosted its firepower by integrating machine-gun-carrying troops into its regiments.

The speed and spirit of the cavalry were emphasized. Mounted men would “strike so quickly as to take the enemy … before he can prepare to receive the attack” and then “by the moral effect and speed of galloping horsemen, destroy the enemy’s will to resist.” Cavalrymen quoted the old maxim: “Victory is gained not by the number killed but by the number frightened.”

There was some debate over the most effective cavalry weapon. Some said the pistol. Others said that even a man lying behind a machine gun found it extremely unsettling to have the point of a sword bearing down on him at the speed of a horse and with the force of a horse and rider behind it. In 1922, Major Patton, then commander of the 3rd Squadron, 3rd Cavalry at Fort Myer, described the cavalryman’s spirit in terms that left no doubt as to its value: “The fierce frenzy of hate and determination flashing from the bloodshot eyes squinting behind the glittering steel is what wins.”

Training at VMI

But these tactics were useless unless the cavalry had officers and men who were trained to ride, and ride well. At 7:30 each morning at Fort Myer, the bugle blew “Boots and Saddles,” and the cavalry cadets saddled up for equitation classes: slow trotting, galloping, jumping, and general horsemanship.

The trainees already knew the basics about riding, having learned them at school. These instructions started with the cadet simply sitting on the horse holding the reins. It proceeded to gripping the horse with the legs, then prodding the horse from a walk to a trot, then the canter, the gallop, the left-leg lead, and the right-leg lead. The goal, finally, was for each cadet to ride with ease and to jump with his reins knotted before the saddle, arms folded across his chest, feet out of the stirrups, and campaign hat strapped over his eyes.

Squad, platoon, and troop drills followed equitation. They were conducted on a dusty drill field, a half-mile long and a quarter-mile wide. These drills, like infantry drills, were ways of getting men and horses from one place to another in an orderly manner—column of twos (the usual march formation), column of fours, and parade formations. The cadets also practiced changing from marching formation (column) to fighting formation (line). Occasionally the cadets might spread out in two long lines, one right behind the other, for a controlled charge.

At VMI, drill included practice with a cavalry saber, which was a heavy, perfectly straight blade almost three feet long (designed by young lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr., in 1913), rather than the curved, scimitar-shaped blade. When charging mounted troops, a cavalryman was to ride down on the enemy soldier with his saber thrust out ahead, arm stiff and rotated slightly inward, run the man through, then let the momentum of the horse pull the blade out as he continued ahead.

The riding drill would continue until 10 am, and at times included long rides in the hot sun along the dusty roads of rural Virginia. Returning to the corral, the cadets were hot, thirsty, and worn out. Their equipment was in foul shape, and the horses were lathered and covered with powdery dust. Then the real work began.

The Horse Always Came First

Even before getting himself a drink of water, a cadet had to take care of his horse. First, he had to take the saddle off, clean it, and put it away. Then he had to walk his horse until it cooled down. Then came grooming. A cadet could not simply throw water on his horse to remove the dust. He had to go over the horse thoroughly with a metal-toothed currycomb, then stroke him with a good strong brush.

All of this usually took about an hour and a half. The grooming was hard labor, each cadet stripped to the waist in the hot morning air. Louie Roberts began to learn of the drawbacks of a black horse. The labor was made easier, however, by a constant exchange of wisecracks and exaggerated tales of exploits in nearby Washington. A cadet was finished only after a sergeant inspected the horse and said he was finished. If the horse was not ready, the cadet had to go back over it again.

Once finished, a cadet could return to the tall, pyramid-shaped tent he shared with three other cadets, pick up a towel, and walk over to the dispensary for a shower. Then came lunch at one of the red brick barracks, where gallons of ice-cold lemonade and large quantities of usually good food were served.

The cadets used transportation other than horses on one field exercise. Automobiles modified to go off road (called “scout cars”) had recently been added to cavalry units for reconnaissance duties. The cadets wanted to try one, but the Fort Myer cavalry lacked money to buy gas for this purpose. The cadets were curious enough about the car, however, that they chipped in for the gas and tried it out, having a great time driving more on road than off.

Meanwhile, like the cadets, the U.S. military was becoming curious about making greater use of mechanized vehicles. This included even the cavalry to a limited extent. Besides scout cars, in the late 1920s the cavalry also experimented with “portee cavalry”: using trucks and other motor vehicles to transport horses and riders long distances. The idea was not to replace the horse with a machine, but to save the horse for its really essential duties.

A New Military Concept Threatens the Cav

The real threat to the horse cavalry began in October 1927, when Dwight Davis, Secretary of War under President Coolidge, visited England. The English, struggling to avoid the static warfare of World War I, were testing a new concept: an independent force that included units of the combat arms—artillery, infantry, and cavalry—and substituted motorized transportation for animal transportation as much as possible. It was called the Experimental Mechanized Force, and Secretary Davis saw it demonstrated on his visit.

Davis had combat experience (he was also the man who donated the Davis Cup to tennis after being half of the team that won the U.S. doubles championship three years in a row around 1900), and he liked what he saw. When he returned to the United States, he told the Army Chief of Staff, General Charles P. Summerall, to establish a pilot program to test a U.S. Experimental Mechanized Force.

This force was to be composed of an infantry battalion transported in war-surplus trucks, a field artillery battalion with truck-transported guns, a cavalry armored car troop (even though the cavalry did not then have an armored car troop), various support elements, and the key component: two tank battalions and a tank platoon.

The new force was a definite break from previous U.S. Army organizations. The National Defense Act of 1920 had specifically confined tanks to the infantry. But tying tanks to infantry had slowed the development of tank tactics, and of tanks themselves, to the lumbering walk of an infantryman. A new dynamic was needed. So the commander of this new experimental force was not bound by the regulations of any one branch. He answered only to the War Department.

The War Office Looks Again at Mechanization

When units of the Experimental Mechanized Force began reporting to Camp Meade, Md., the first week of July 1928, most of the tanks were the same Renaults that the United States had used in World War I, only now older and even more prone to breakdowns.

The force’s “armored cars” of the armored car troop were hastily assembled by Ordnance Corps personnel or troop mechanics at Camp Meade, who simply added boilerplate or light armor plates to the chassis of a Dodge, a La Salle, and other cars that were handy. Armed with machine guns and equipped with radios, they were meant to be used for reconnaissance.

Not surprisingly, trial maneuvers of the force were not impressive. Assigned new tasks for which it was not designed, the obsolete equipment broke down. Insufficient vehicles had been used to test new theories of combined-arms employment. The force was dissolved after three months.

But the War Office also had appointed a board to study mechanization. Despite the showing of the experimental force, on October 1, 1928, the board recommended establishment of a permanent mechanized force.

Still, it was not until late 1930, when Davis was no longer Secretary of War and Summerall was about to leave office also, that Summerall actually ordered: “Assemble the mechanized force now.… Make it permanent, not temporary.”

But the force was again inadequate. Of the mere 15 fighting tanks in the unit, all but three were the old 1917 model Renaults (although some had been modified with new engines). This force also was short-lived. The new Army Chief of Staff, General Douglas MacArthur, dissolved it in May 1931. He had a different approach to mechanization, and it directly affected the cavalry.

Problems With Old Equipment

In the meantime, the cadets at Fort Myer also experimented with mechanization beyond the scout car. They were quick to grasp the advantage of the car over the horse for their purpose—quick, long-distance transportation on weeknights and on weekends. From 3:30 pm until 11 pm each weekday, cadets were free to go wherever they wanted. On weekends, while a third of the group had to stay to take care of the horses, two-thirds of the cadets were officially off from Saturday noon until reveille Monday morning.

Still, like the mechanized force, they, too, had problems due to old equipment. Charlie Wills, a VMI engineering cadet from Petersburg, Va., and a couple of buddies had bought a 1925 Star touring car with a removable canvas top. About 11 pm one Sunday, they started from Richmond headed back to Fort Myer. Soon after leaving Richmond, they got part way up a long hill on Route 1 and the Star stalled. They got out, pushed it to the top of the hill, and jumped in again as it rolled down the other side. They finally got it started on the way down, but the same thing happened at the next long hill. No amount of engineering expertise could keep it going. They performed this push-and-jump-in maneuver frequently until they arrived in camp an hour late and were rewarded with three weeks’ confinement to post.

Then there was the 1923 Dodge that no driver could rely on: “You point it one way, by the time you got there, you had swerved somewhere else.”

Charlie Dayhuff was driving his dilapidated Ford onto the post one afternoon with another cadet, Buddy Shell, the lanky son of an army officer from Fort Monroe, Va., when they saw Major Patton walking nearby. Patton was stationed across the river in Washington in the Office of the Chief of Cavalry, and that spring and summer of 1930, his articles warning of the danger of relying on mechanization had appeared in installments in The Cavalry Journal. Cadet Dayhuff had met Major Patton’s older daughter Bee, taken her out, and gotten to know her father slightly.

Dayhuff stopped and politely asked Patton if he wanted a ride. As Dayhuff remembered years later, Patton’s response was, “Ride that goddamn thing? If I was post commander, I wouldn’t even allow it on post.” This was possibly Patton’s most succinct expression of his opinion of mechanization.

All of the cadet’s activity, during the day by horse and during nights and on weekends by car, produced some very tired cavalrymen. A number of times during the hot, summer days, some cadets would be off riding on assigned maneuvers while others waited their turn. One cadet remembered that the waiting cadets would stretch out on the ground, one after another, and go quickly to sleep holding their horses’ reins. As a cadet slept, his horse would wander about and graze, still managing not to step on his rider or on another cadet stretched out nearby.

During the next to last week of camp, the cadets traveled to a target range about 25 miles south of Fort Myer to qualify with their pistols. Instead of riding there on horseback, they drove their motley collection of 12 old cars.

In his old Ford, Charlie Dayhuff led the convoy down the road in a single column. As they approached the range buildings, he signaled, and the cadet drivers fanned out impressively, part to the left and part to the right of him, just as on their mounted maneuvers. Then all came to a stop in a straight line right in front of the main building. An old horse soldier standing nearby eyed the cars and asked one of their instructors, “What the hell are you doing teaching those kids those things? I thought you were Cavalrymen.”

It was a prophetic glimpse of things to come for the horse cavalry.

‘Boots and Saddles’ Now Means ‘Crank ‘Er Up’

New Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur’s idea for mechanization was to require all combat branches to mechanize to the extent their budgets would allow. As part of this plan, on May 1, 1931, he ordered parts of the newly reformed “permanent” mechanized force, including some tanks, to be subsumed into the cavalry as a reinforced regiment. Shortly afterward, he also ordered two cavalry regiments to turn in their horses for tanks.

Yet, the old National Defense Act of 1920 still provided that only the infantry was to have tanks. MacArthur got around it by referring to the tanks sent to the cavalry as “combat cars.” (With this subterfuge, he was carrying on something of a tradition—the use of the term “tank” had evolved originally when the first of those vehicles was sent from Britain to France during World War I under tight security in crates labeled “desert water carrier.”)

The cavalry now was forced to deal directly with tanks. As an article in the Louisville Courier Journal reported soon after the order: “‘Boots and saddles’ now means ‘crank ’er up.”’

MacArthur’s action reflected the two schools of thought about horse vs. machine that had existed in the cavalry for several years. To some it seemed obvious that improved machines could perform all the traditional cavalry functions better than horses. Others, and in the 1920s they were the ones in control of the cavalry, believed firmly that the horse could not be replaced. Major Patton and like thinkers were in this group. They maintained that the horse had to remain the focus of cavalry—only the horse had the ability to perform all the cavalry functions in all weather and all terrains. Patton went even further: “When Sampson took the fresh jawbone of an ass and slew a thousand men therewith he probably started such a vogue for the weapon, especially among the Philistines, that for years no prudent donkey dared to bray.… Today machines hold the place formerly occupied by the jawbone.… They too shall pass.”

Yet, a smoke-belching tank reeking of oil had rumbled into the stable yard, parked, and now stood there among the bags of oats, showing every intention of staying. It was disturbing some of the horses.

Cavalry Seeks Middle Ground

In an attempt to reassure the horse advocates, the then Chief of Cavalry sought a middle ground: “[I]n the future we will have two types of cavalry, one with armored motor vehicles, giving speed, strategical mobility, and great fighting power of modern machines; the other with horses, armed with the latest automatic firearms for use in tactical roles and for operations in difficult terrain where the horse still gives us the greatest mobility.”

Meanwhile, the War Department proceeded to organize the new mechanized cavalry unit. It chose Fort Knox, Ky., for its station and designated it as the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized).

This new unit was placed under the command of the V Army Corps area commander. The Chief of Cavalry’s role was limited to making recommendations and conducting inspections, the latter only under War Department direction.

In early 1933, the 1st Cavalry was moved to Fort Knox from Marfa, Texas, and became the first cavalry unit to give up its horses for combat cars. But political pressure from local jurisdictions that would lose their cavalry regiments kept a second regiment from surrendering its horses and moving to Fort Knox until 1936. Then the 13th Cavalry was moved from the Cavalry School at Fort Riley, Kan., to join the 7th Cavalry Brigade at Fort Knox.

At its other posts, the horse cavalry continued to train for its mission while nervously looking out of the comer of its eye at the tank revving its engines in the stable yard.

The Twilight of the U.S. Cavalry

More and more the horse seemed an anachronism, yet it was an alluring anachronism. And this allure had always been a factor in its survival. For some, horses alone were fascinating enough. For others there was the history: knights in armor, J.E.B. Stuart and Phil Sheridan, the old Indian fighters, Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders. Then the sports: polo, fox hunting, jumping. “If any branch of the Old Army evoked romance,” wrote historian Edward M. Coffman recently in his foreword to The Twilight of the U.S. Cavalry by General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., “it was the pageantry of cavalry, with the military horsemen in full panoply, the chattering bugles, and the snapping red and white guidons.” All these factors helped the horse cavalry survive deep into the 1930s.

A story making the rounds of the cavalry posts then, from Fort Myer to Fort Meade, SD, told of a brigadier in the British Army who asked a lieutenant of the horse cavalry: “What is the value of the Launcers in the present-day Army?” The lieutenant hesitated and the brigadier insisted, “Come, come now, Leftenant. What is the value of the Launcers in modern warfare?” The lieutenant finally replied, “Well, my Lord, you must admit that the Launcers add a bit of tone to what would otherwise be a very vulgar sort of a brawl.”

But the dashing history, parades, and pageantry were being scrutinized by colder and colder eyes. In 1938, as World War II approached, two hard-driving men were appointed to important cavalry commands, and they went head-to-head over horse vs. machine. Major General John K. Herr was appointed Chief of Cavalry, and Brig. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee was appointed commander of the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized). They fought to the finish with only one command left standing at the end.

Both were cavalry officers who early in their careers had distinguished themselves as excellent riders. Herr was one of the army’s best polo players, a member of the legendary 1923 U.S. team that defeated a strongly favored British team. Chaffee was the youngest member of the 1911 U.S. team in the International Horse Show in London during George V’s Coronation Week and a former student at the French Cavalry School at Saumur, France (where he learned to jump over fully set dinner tables without overturning a glass of water).

Both were graduates of the U.S. Military Academy. Both had served in World War I as staff officers—Herr as the chief of staff of the 30th Infantry Division (“Old Hickory”) and Chaffee on the general staff at the Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Force.

A major difference, however, was that Chaffee was in General Summerall’s Operations and Training Section, G-3, in 1927 when Secretary Davis and Summerall began what was to be the modern tank corps. At that point Chaffee had never ridden in a tank, but the more he learned about tanks the more interested he became. On the other hand, when Herr was appointed in 1938, he had no known sympathy for tanks and had just spent the previous two and a half years commanding the legendary Indian fighters, the 7th Cavalry, at Fort Bliss, Texas.

Seeking a Proper Balance Between Horse and Mechs

Herr soon made his point of view known. In congressional testimony in 1939 he stated the cavalry must “maintain a proper balance between horse and mechanized units” in order to maintain maximum efficiency because mechanized vehicles were “unable, even though moving across country, to negotiate the many difficult types of terrain such as woods, bogs, streams, stone walls, and ditches which are easy for the horse.” The number of mechanized units in the cavalry could increase, but no man or horse would be given up in order to organize these new units. As he expressed it: “We must not be misled to our own detriment to assume that the untried machine can displace the proved and tried horse.”

Chaffee, on the other hand, was trying to increase the size of his “combat car” brigade and form a full division. At first Chaffee thought he had Herr’s support. But time passed, and the plans for the expansion lay quietly on some War Office desk. When he read Herr’s public comments, he realized no support would be forthcoming from that direction. He must turn elsewhere.

In April 1939, word arrived that General George C. Marshall would soon be appointed chief of staff. Marshall was less attached to set army practices than previous chiefs of staff. Shortly afterward, Chaffee persuaded Marshall to listen to his views. He found Marshall open to expanding the mechanized brigade but still unconvinced.

That was how things stood in September 1939, when the German blitzkrieg struck Poland. Only a few months earlier, The Cavalry Journal had carried articles noting Poland’s large commitment to cavalry and explaining how Poland planned to use it with the unspoken message that here was an admirable European state that still believed strongly in the value of its horses in war. Then the Germans attacked Poland from the north, west, and south. Massed columns of German tanks, backed by waves of dive bombers and followed by mechanized infantry pouring through the gaps created by tanks and planes, found the Polish cavalry completely inadequate.

Lessons Learned from Hitler’s Blitzkreig

General Chaffee delivered a lecture at the Army War College only a few weeks after the invasion of Poland. He discussed in some detail the success of the blitzkrieg. He concluded: “There is no longer any shadow of a doubt as to the efficiency of well trained and boldly led mechanized forces in any war of movement [and] that they cannot be combated by infantry and horse cavalry alone.” He further recommended the establishment of at least four mechanized cavalry divisions in the near future.

Herr continued to oppose expanding the 7th Brigade at the expense of horse cavalry, but the War Department was beginning to grow tired of his intransigence. General Marshall ordered war-game maneuvers to be held April 12-25 and May 5-25, 1940, in Georgia and Louisiana, and for the first time a mechanized unit larger than a brigade was to be employed by combining Chaffee’s combat cars with some infantry tanks.

Several months before the maneuvers, Patton, now a colonel and commander of the horse cavalry at Fort Myer, slipped inside information about the general maneuver scenario and the cavalry’s particular mission to the head of the horse cavalry arm in the maneuvers, his friend Maj. Gen. Kenyon Joyce. Patton, who had been uncharacteristically silent for a while, also managed to get himself appointed an umpire for the maneuvers so he could observe firsthand what happened.

What happened was that Joyce’s horses were unable to keep pace with Chaffee’s combat cars, particularly during the fourth phase of the maneuvers. In that phase the great majority of the tanks were on the side of the Red army while the horses were with the Blue. Red, spearheaded by Chaffee’s tanks, swept around to attack Blue’s flanks. Blue’s horses rushed to stop them, but the Red tanks consistently beat the horses to vital unguarded road junctions and other crucial sites. They then defended these sites long enough for Red’s line troops, following behind the tanks, to establish positions that critically endangered the Blue army. Even with Patton’s inside information, the horse cavalry could not contain the mechanized forces.

That same May, German panzers moved quickly into Holland, Belgium, and France.

On the last day of the maneuvers, May 25, 1940, an impromptu conference on mechanization was held in the basement of the Alexandria, La., high school. Present were General Chaffee, General Frank Andrews of the War Department General Staff (Marshall’s man), and a few others, including, somehow, Colonel Patton. Not included was General Herr, although he was in Louisiana at the time. Those present concluded unanimously “that development of mechanized units could no longer be delayed, and that such units must be removed from the control of the traditional branches to become a separate organization,” as Mildred H. Gillie reports in her book Forging the Thunderbolt. On July 10, 1940, General Marshall issued the order creating an Armored Force. General Chaffee was appointed its first commander.

Office of Chief of Cavalry Eliminated

The days of the horse cavalry were numbered. It lasted until March 9, 1942, when the office of Chief of Cavalry was eliminated and its functions were transferred to the newly formed Army Ground Forces. General Herr retired from active duty a few days before the transfer. But by then, the meeting-and-memo war was over, and the real war had begun. None of the 10 remaining horse cavalry regiments went overseas to World War II with their horses.

One regiment of the U.S. Cavalry, however, did meet the enemy with its horses. Its horses were already overseas, and the enemy—with tanks—came to meet them.

On December 22, 1941, the Japanese landed on Luzon Island in the Philippines approximately a hundred miles north of the head of Manila Bay. Quickly it became apparent that the strength of the Japanese force and the lack of training of the Philippine army meant that the most America could expect early on was to delay the enemy from its drive south toward Manila.

One of the best-trained U.S. units in the Philippines was the 26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scouts). This horse cavalry unit, organized in 1922, was composed of hand-picked Filipino NCOs and men led by American officers.

The 26th, fighting dismounted, met the enemy within site of the beach, but it was hit with infantry, tanks, planes, and naval bombardment and forced to withdraw to a second holding position.

Here occurred the first contact between U.S. mounted troops and enemy tanks. Although the engagement began almost humorously, it ended in near disaster.

In the general withdrawal, the U.S. forces had broken off contact with the Japanese. After setting up its second holding position, the 26th was ordered to move back to still another new position. It was night, and the regiment was strung out along either side of a paved road. As it was preparing to mount up and leave, several U.S. light tanks that had been up ahead passed back through the ranks of the 26th and on down the road.

U.S. Mounted Troops Meet Enemy Tanks

Next, Captain John Wheeler, commander of Troop E at the head of the cavalrymen saw two tanks clank down the middle of the road toward him and stop. He rode up to them yelling to get moving. A turret on one opened, a head popped up, the captain let loose a few choice words, and the head popped down again, pulling the turret closed. Then the tank opened fire. It was Japanese.

Suddenly several tanks were in the midst of the 26th firing their guns, catching some troopers up on their horses, others still on the ground. Along each side of the dark road were high banks and agricultural fences of barbed wire. The cavalrymen had no room or time to deploy. Horses bucked and reared. Mounted troops ran into dismounted. As one officer tried to mount, his horse bolted, catching his foot in the stirrup and dragging him along the road until he was knocked unconscious. Several troopers were trampled by terrified horses. Mounted men and riderless horses ran down the road in utter confusion.

Captain Wheeler and Major Thomas J.H. Trapnell were bringing up the rear of the rush of horsemen when they came to a bridge. Just then, on the other side of the bridge, the regimental veterinarian truck drove up. Wheeler and Trapnell dashed across the bridge to the truck, and under heavy machine-gun fire from the pursuing Japanese tanks, they and the vet pushed the truck onto the middle of the bridge and set it on fire.

This action stopped the Japanese tankers on the far side of the bridge, and the 26th was able to restore order. But this fight had been a defeat, much like the cavalry’s first encounter with the machine gun 23 years earlier.

As the Japanese continued their advance south, the 26th fought courageously and fell back, and fought and fell back again, down Luzon Island.

About three weeks after the Japanese landing, in a small village of thatched-roofed grass huts on the west coast of Luzon, the 26th executed the U.S. Army’s last horse cavalry charge. It was a mad dash by a little over 20 troopers plunging their horses forward, their pistols flashing, into the startled faces of an advance unit of Japanese infantry. The charge halted the Japanese advance, but only briefly. Even with the subsequent aid of a full division of Filipino troops, the action only bought a 24-hour delay in the steady Japanese advance down Luzon and onto the Bataan Peninsula.

The same Captain Wheeler who had met the tanks was the commander of the 26th’s forces at the village when the cavalry charged. He was wounded in the leg. Later he was captured when the U.S. forces surrendered at Bataan, and he died in captivity.

History Still Echoes at Fort Myer

Other U.S. Cavalry units were more successful fighting as armored units in WWII, and a number of individual cavalrymen played vital roles in the U.S. victory in the war. Ernest N. Harmon, who wrote about the cavalry’s unfortunate experiences in WWI, commanded armored divisions in North Africa, Italy, Belgium, and Germany. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., a tough polo player who was commissioned in the cavalry in 1917, commanded the 3rd Infantry Division in Sicily, the VI Corps at Anzio and during the invasion of southern France, and the Fifth Army in Italy. And, of course, giving invaluable aid to the victory was George S. Patton, Jr.

Almost none of the ROTC cadet-trainees went into the military directly after graduation in 1931—the United States wanted a small standing army then. However, they served in a surprisingly wide variety of capacities during the war.

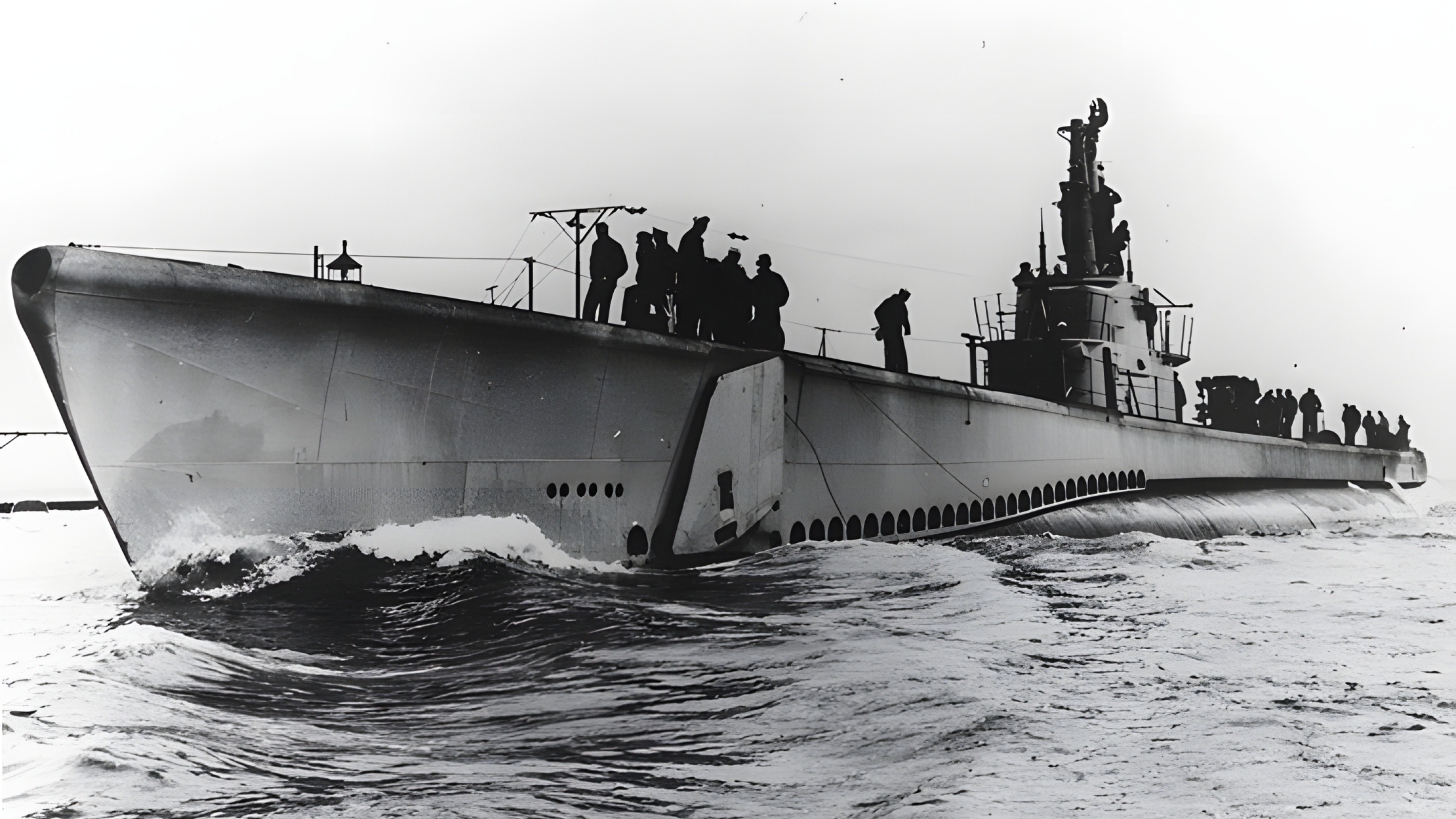

Charlie Wills, part-owner of the Star automobile, somehow got into the navy and served as an engineering officer on a destroyer escorting convoys across the North Atlantic. Charlie Dayhuff was in Military Intelligence stationed in Brazil searching for German submarine hideouts and monitoring suspected raw rubber smuggling. His lanky friend Buddy Shell became a Marine and was severely wounded when a Japanese shell landed in his artillery command post just inland from the beach during the second day of the invasion of Saipan. He survived to become a lieutenant general and superintendent at VMI.

Eddie Pulliam, of the one-eyed horse, trained with barrage balloons—large, thick-skinned, dirigible-shaped balloons sent aloft over U.S. and English cities to deter low-flying enemy aircraft. He ended up as the executive officer of a mobile replacement station that moved across the French countryside housing and feeding troops on their way to the front lines.

Louie Roberts, of the small black horse, was one of the few to serve with the horse cavalry’s old nemesis—tanks. Shortly before the Normandy invasion, he and a British tank officer were ordered to swap places. Roberts became the commander of a British tank squadron training in England with experimental tanks and accompanied the unit in the invasion. Later, after MacArthur’s return to the Philippines, he led U.S. tanks against the Japanese.

There still are horses at Fort Myer. The low, red brick stables stand today where they did in the summer of 1930, and before that. Some shelter horses whose duty is to accompany funerals in nearby Arlington National Cemetery, where so many cavalrymen now rest.

The horses continue to be cared for by young troopers, who must groom them carefully after the horses’ duties are over, and before they themselves are allowed to do anything else.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments