By Pat McTaggart

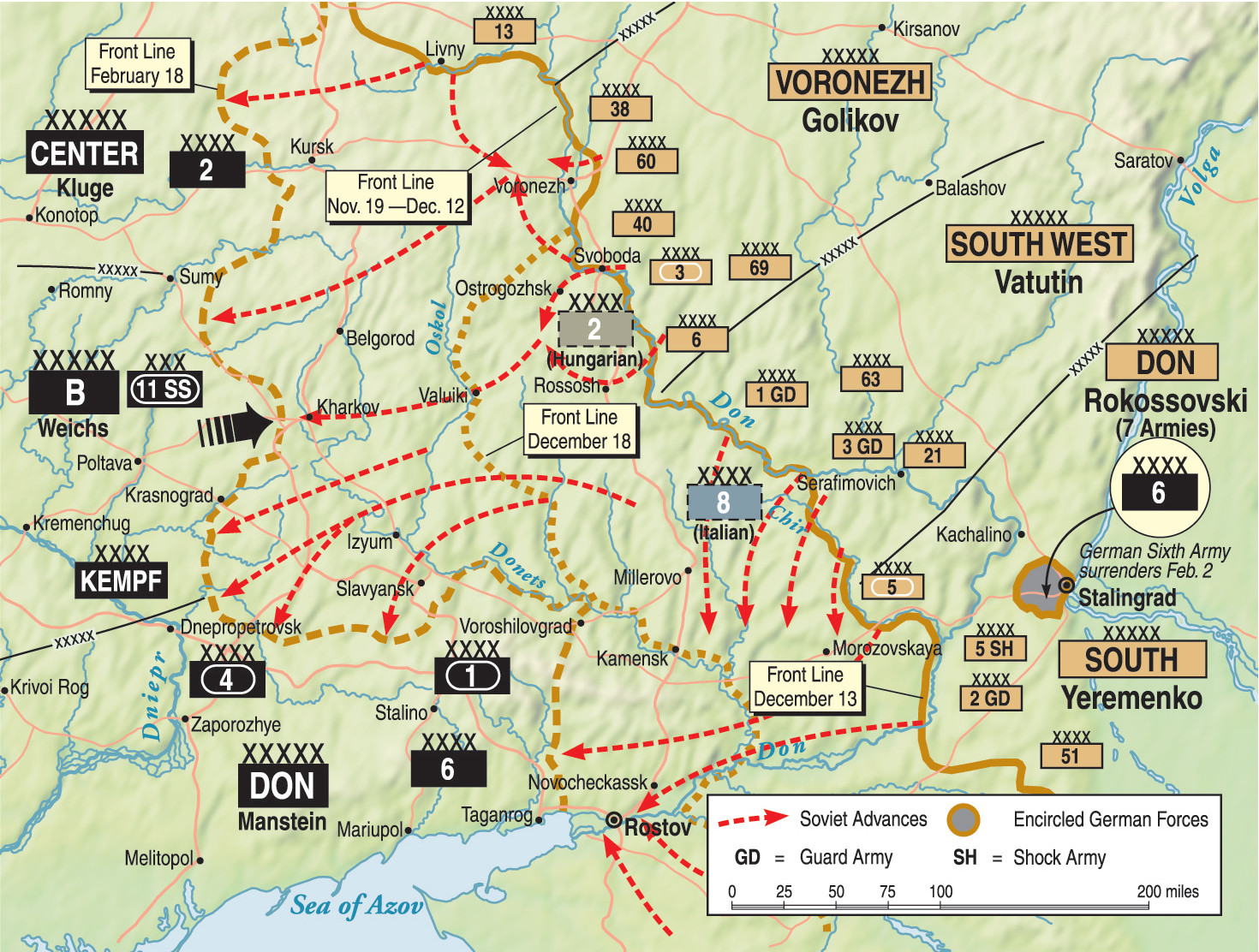

As Adolf Hitler’s vaunted Sixth Army lay in its death throes in the ruins of Stalingrad, German forces to the west of the city faced their own kind of hell. The inner ring of the Russians’ iron grip at Stalingrad was tasked with the total destruction of German and other Axis troops within the city, but Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin wanted more. In conjunction with the Soviet High Command (STAVKA), Stalin set forth an ambitious plan designed to liberate the Don Basin from Kursk in the north to the Sea of Azov in the south, bringing the vital agricultural and mineral-rich area once more under Russian control.

Operation Gallop: Striking the Southern Flank

Germany’s allied armies were a shambles. The Hungarian Second Army and the Italian Eighth Army, positioned along the upper Don River, were shattered by General Filipp Ivanovich Golikov’s Voronezh Front, causing a yawning gap south of the German Second Army, which was assigned to defend the Voronezh area.

Farther south, General Nikolai Fyodorovich Vatutin’s South West Front, despite heavy opposition, moved toward Voroshilovgrad and Starobelsk. In the Caucasus and along the Donets River, the German troops of Heeresgruppe A (Army Group A) were in a race to the death to escape being trapped by advancing armies of the Trans-Caucasus and the Stalingrad Fronts.

In mid-January, Stalin and STAVKA saw a very distinct possibility of forcing the entire southern flank of the German Army in the east to collapse. With a victory at Stalingrad all but assured, Soviet military planners developed operations aimed at pushing the Germans back to the Dniepr River. The more optimistic planners, including Stalin, hoped for an even bigger push.

A two-pronged attack was finally approved. Operation Skachok (Gallop) would use Vatutin’s South West Front to clear the southern Don Basin of the enemy and push him back to the Dniepr. On Vatutin’s right flank, Golikov’s Voronezh Front was ordered to take Kharkov and then follow the retreating Germans as far west as possible in an operation called Zvezda (Star).

The German Army in Disarray

The German forces facing Vatutin had been ground down by weeks of fighting and retreat. Lt. Gen. Fedor Mikhailovich Kharitonov’s Sixth Army and Lt. Gen. Vasilii I. Kuznetsov’s First Guards Army were fast approaching the Aydar River in the Starobelsk area, while the Third Guards Army under Lt. Gen. Dmitri Danilovich Lelyushenko was threatening to cross the Donets River west of Voroshilovgrad. South of Lelyushenko, Lt. Gen. Ivan Timofeevich Schlemin’s Fifth Tank Army was also moving toward the eastern bank of the Donets.

Vatutin also had a combined arms group commanded by Lt. Gen. Markian Mikhailovich Popov, which contained nearly half of the South West Front’s armor. In total, Vatutin had more than 500 tanks and about 325,000 men to fulfill his mission.

Facing the South West Front was a hodgepodge of German units in the process of trying to regain some kind of defensive line and command control. About 160,000 men and 100 tanks from several decimated divisions struggled to pull themselves into some kind of cohesive force to meet the advancing Soviet forces.

The First Panzer Army, commanded by General Eberhard von Mackensen, was just arriving from a grueling retreat from the Caucasus. It had about 40 combat-ready tanks and an estimated 40,000 troops. Army Abteilung Hollidt was a conglomeration of infantry and panzer division remnants. Commanded by General Karl Hollidt, the unit had about 100,000 men and 60 tanks. Another 20,000 troops came from various support and garrison units.

General Nikolai Fyodorovich Vatutin: A Gifted Strategist

Aware of the enemy disorganization facing him, Vatutin planned his actions accordingly. Born in 1901, Vatutin joined the Red Army in 1920. He saw service during the Russian Civil War and then attended the Frunze Academy, graduating in 1929. Furthering his career, Vatutin attended and graduated from the General Staff Academy and served on the General Staff from 1937-1940. During the Battle for Moscow, he distinguished himself as chief of staff of the Northwestern Front, and in 1942 he was named commander of the South West Front.

Vatutin was considered a gifted strategist, and his opinions were highly valued. He was enthusiastic about the possibility of liberating the Lower Don Basin and destroying the German units defending it, and STAVKA gave him great latitude in forming his plan of attack, which he worked out with his army commanders and staff.

The main blow was to come from the First Guards and Third Guards Armies, which would take Stalino and then Mariupol on the Sea of Azov. This action, supported by Group Popov and the Fifth Tank Army, would trap most of the German units on the Donets River Line south of Kharkov. Divisions of the Southern Front, on Vatutin’s left flank, would cooperate by advancing along the Sea of Azov to Rostov and beyond.

In theory, the plan was a good one. Intelligence reports indicated that the Germans were in a state of near panic. Other reports stated that enemy troops were hastily withdrawing from the entire area, which gave Vatutin the view that his operation was a means to crush a beaten and demoralized foe.

Strengthening Heeresgruppe Süd

The Soviet assessments were wrong to a large degree. Although the Germans were disorganized, commanders were working together to retain a viable fighting force. German supply lines were much closer since the retreat from the Stalingrad sector, and the ability to form ad hoc units around regimental and divisional cadre was succeeding.

There was also another major factor working for the Germans. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein was in command of the area slated for the Soviet offensive. Architect of the 1940 Ardennes strike against France and the conqueror of Sevastopol in 1942, von Manstein was regarded as having one of the best strategic and tactical minds in the Wehrmacht.

Although the divisions of his Heeresgruppe (Army Group) Don, which became Heeresgruppe Süd (South) in mid-February, were battered, the German commander was already planning a response for what he correctly assumed to be a major Soviet attack in the Don Basin. He knew the Red Army supply lines had greatly lengthened as his own decreased, making it difficult for Soviet armor to receive proper fuel and ammunition replenishment. He also knew that although the Russians had superiority in manpower and equipment their reserves were lacking in numbers for a prolonged attack and breakthrough.

Von Manstein was also lucky in another regard. While the debacle at Stalingrad was still being played out, he had managed to talk Hitler into allowing most of the German forces in the Caucasus to withdraw before being cut off. By the end of January, many of those units, including the First Panzer Army, were regrouping in the Don Basin. The Fourth Panzer Army, commanded by Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth, was also in the process of getting out of the Soviet trap.

As he pressed the issue of the vulnerability of the entire southern sector of the Eastern Front, von Manstein persuaded the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht–German Armed Forces High Command) to release six divisions and two infantry brigades from Western Europe and send them to Heeresgruppe Süd. Among the divisions released were three superbly equipped SS divisions, which had been resting and refitting after the hard-fought 1942 campaign.

The Soviet Offensive Begins

On February 1, 1943, Golikov’s Voronezh Front began its attack to liberate Kharkov. Excellent progress was made during the first days of the offensive, with General Ivan Danilovich Chernyakowskii’s 60th Army taking Kursk on February 8. As Kursk fell, Golikov’s 40th and 69th Armies, along with the Third Tank Army, advanced on Kharkov, slamming their way through the undermanned defenses of the German Second Army.

Two days before Golikov’s offensive began, Vatutin launched Operation Gallop. On January 29, Kuznetsov’s First Guards Army crossed the Aydar River and hit General Gustav Schmidt’s 19th Panzer Division in the Kabanye–Kromennaya area along the Dnester River. Reeling under a series of hammer blows, the Germans were forced to retreat under a constant barrage of Soviet artillery.

On Kuznetsov’s right flank, Kharitonov’s Sixth Army, after crossing the Aydar, smashed into elements of Colonel Herbert Michaelis’s 298th Infantry Division. With the bulk of the 298th dug in along the Krasnaya River, the forward elements of the division were brushed aside by the advancing Soviets.

Pursuing the retreating Germans, Kharitonov’s 15th Rifle Corps made it to the Krasnaya before being stopped by the 298th’s makeshift defenses on the western bank. Under heavy fire, the 350th Rifle Division forced crossings north and south of Kupyansk and established bridgeheads on the German side of the river, but further progress was retarded until reinforcements arrived on the scene.

January 30 found the First Guards Army crossing the Krasnaya near the town of Krasny Liman. Pleased with the progress of his assault troops, Vatutin ordered Group Popov to advance and form up at the juncture of the First Guards and Sixth Armies in order to exploit any major breaches in the German line.

For the next few days, Vatutin continued to receive good news from the front. His planning of Gallop seemed to be validated as reports came from the First Guards Army stating that Kremennaya had fallen, the 19th Panzer Division was retreating toward Lisichansk to the south, and that Krasny Liman was also taken.

In the Sixth Army sector, Kharitonov finally crossed the Krasnaya River after the 298th Infantry Division, fearing encirclement by advancing units of the Sixth Army and the Voronezh Front’s Third Tank Army, abandoned its positions on the eastern bank. From February 2-5, the 298th fought through Soviet units already in its rear before finally reaching a new defensive line around Chuguyev on the Northern Donets River.

Sixth Army units also forced General Georg Postel’s 320th Infantry Division to retreat from the Krasnaya. While the Sixth Rifle Division attempted to surround Postel’s division, the 267th Rifle Division and 106th Rifle Brigade drove on to Izyum, which would fall on February 5.

Sensing victory, Vatutin sent in Group Popov to act as the vanguard of the Soviet attack. A counterattack by some of the First Panzer Army’s XL Panzer Corps, commanded by General Sigfrid Henrici, halted Popov’s advance in several areas. Other elements of Henrici’s corps struck the First Guards Army around Slavyansk, forcing Kuznetsov to halt his attack. Farther south, Lelyushenko’s Third Guards Army had now crossed the Donets River near Voroshilovgrad and was engaged in breaking through the defenses of Army Abteilung Hollidt.

Preventing a Soviet Breakthrough

The battle around Slavyansk was pivotal for the Germans trying to stop Vatutin’s push westward. As long as the town was in von Manstein’s hands, Vatutin would have to extend his forces to bypass it, lengthening his supply lines and offering his flanks to German counterattacks.

By February 4, Vatutin found himself facing an increasingly stubborn opponent. Elements of Henrici’s XL Panzer Corps were clinging to Slavyansk, fending off the First Guards Army with vicious counterattacks. Kuznetzov threw more units into the battle for the town, but Henrici’s men held firm.

About 55 kilometers east of Slavyansk, the First Guards Army’s Sixth Guards Rifle Corps, commanded by General Ivan Prokofevich Alferov, was embroiled in a savage fight for control of Lisichansk. General Maximilian Fretter-Pico’s XXX Army Corps was charged with the defense of the sectors north and south of the town.

General Karl Casper’s 335th Infantry Division, newly arrived from France, was one of the divisions tasked with defending the area south of Lisichansk near the town of Krymskoye. Alferov’s 44th Guards Rifle Division gained a small bridgehead on the western bank of the Donets and fought off repeated counterattacks by the 335th. Seeing that further assaults were a waste of manpower, Casper ordered his men to cordon off the bridgehead, hoping that reinforcements would be sent to break the Soviet line.

At Lisichansk, Alferov’s 78th Rifle Division tried an end run. The 78th crossed the Northern Donets at several points, but once again German forces moved in to seal them off. For the moment, it was a stalemate.

Frustrated, Vatutin threw the 41st Guards Rifle Division into the Lisichansk battle. Defended by Schmidt’s 19th Panzer, the Soviets had to clear the town street by bloody street. Aided by elements of the 78th Guards and 44th Guards Rifle Divisions, the Russians finally forced Schmidt’s men out of the town to positions in the southwest. The Sixth Guards Rifle Corps followed fast on their heels, but Schmidt was able to work his units like a boxer, bobbing, weaving, and shifting constantly to frustrate any further breakthrough.

Negotiating a Retreat with Hitler

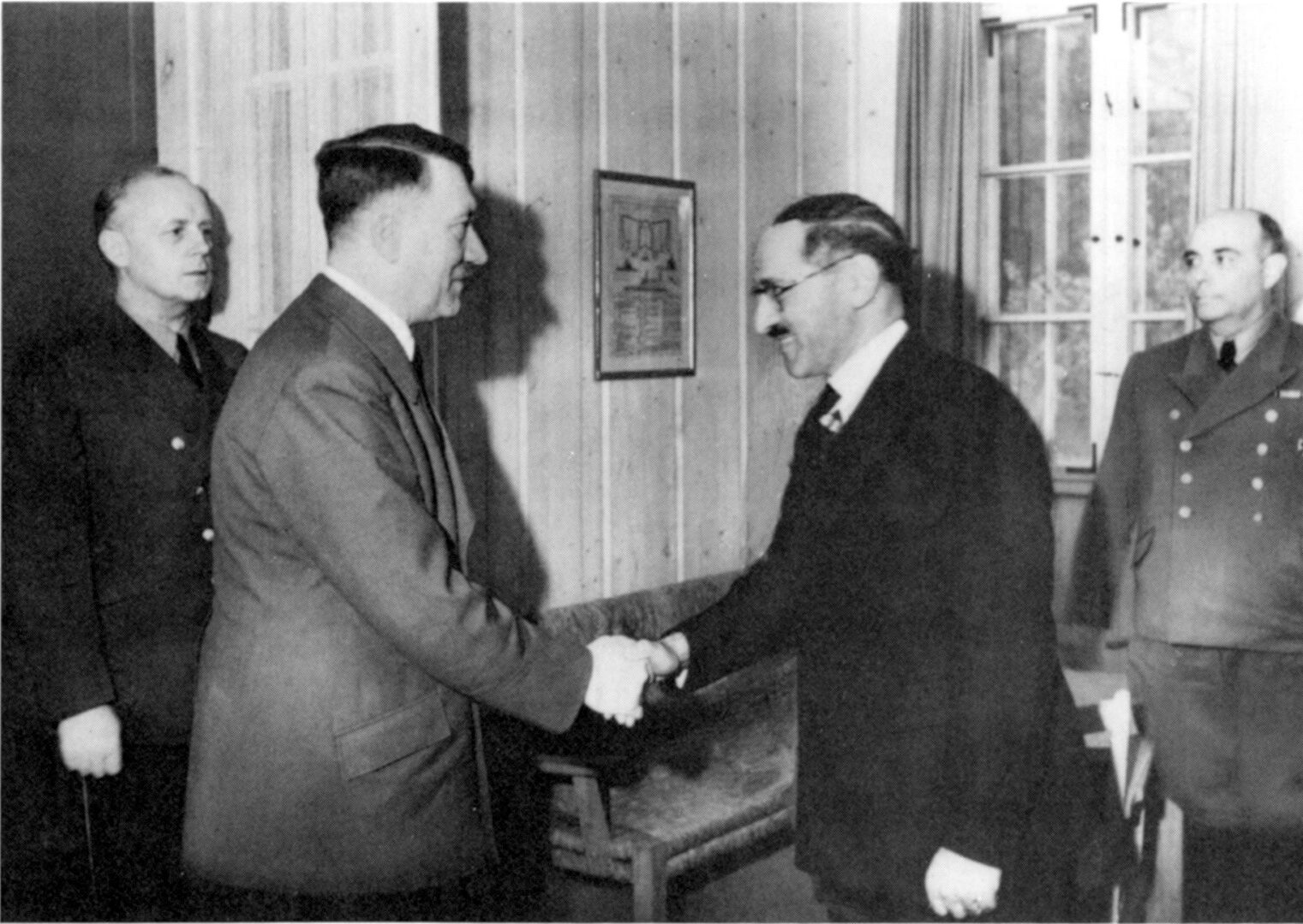

On February 6, Hitler called von Manstein to his headquarters at Zaporozhye. The German leader was surprisingly docile, almost apologetic, as he opened the conversation by taking full responsibility for the Stalingrad disaster. Von Manstein was taken aback by the statement because Hitler never blamed himself for any of the misfortunes suffered by the German Army.

With the surprising admission out of the way, the two men turned to the situation at hand. Von Manstein was blunt as he began explaining the position of his Army Group. He told Hitler that under no circumstances could the area between the Don and the Donets be held with the existing forces available.

“The only question is whether, in trying to hang on to the whole basin, we want to not only lose the area but also Heeresgruppe Don,” he said. “We will also eventually lose Heeresgruppe A. The alternative is to abandon part of the Basin at the right moment to avert the catastrophe threatening to overtake us.”

According to von Manstein, Hitler remained “utterly composed” during the ensuing conversation. Continuing, he told Hitler that trying to hold the entire Basin would allow the Soviets to send strong enough forces to slice through the thinly held German line and envelop the entire southern wing of the Eastern Front. Therefore, he proposed using the First Panzer Army and the Fourth Panzer Army, which were facing General Andrei Ivanovich Yeremenko’s Southern Front, to form a strike force to intercept the forces that Vatutin undoubtedly already had in mind for his continued advance.

Moving the Fourth Panzer Army back from the Lower Don would mean giving up the area between the Lower Don and the Mius River to the armies of Yeremenko’s Southern Front, but it would also shorten the German line. To protect the southern flank, Army Abteilung Hollidt would also have to withdraw to the Mius. It was a risky plan, but the alternative meant almost certain disaster.

When von Manstein finished, it was Hitler’s turn. The Führer could find no flaws in the plan, but his aversion to giving up ground to the enemy was still paramount. He argued that every foot of land cost the Russians men and materials—much more than it cost the Germans. There were also political considerations, such as the effect such a withdrawal would have on Turkey, which was watching developments in Southern Russia very carefully.

Hitler promised reinforcements, cajoled, and used his famous charm and eloquence to convince von Manstein to remain on the Don, but von Manstein would not budge. The impasse went on most of the afternoon, but then Hitler suddenly gave in. Finally having the Führer’s blessing, von Manstein hurriedly flew back to his Stalino headquarters to begin issuing orders for the retreat.

A Fighting Withdrawal

Unless an early thaw suddenly hit the area, armored and mechanized units scheduled to pull back would have little problem reaching the Mius ahead of the Soviets. The infantry units of the Fourth Panzer Army and Army Abteilung Hollidt were a different matter. Vulnerable to Russian armored and mechanized forces, the retreating infantry would have to leave a rear guard to conduct a fighting withdrawal while main elements of the division remained on guard against Soviet ambushes and armored raids.

The Soviets were by no means idle as the Germans prepared to withdraw to the shorter Mius Line. The South Front’s 44th Army took the city of Azov-on-the-Don. Around Salvyansk, where fighting was still raging, Red Army units also took the town of Kramatorsk, some 15 kilometers south of the city.

The following day, February 8, Kharitonov’s Sixth Army liberated Andreyevka on the eastern bank of the Northern Donets, about 50 miles southeast of Kharkov. The Soviet commander then turned his forces northeast to strike at Zmiyev, which was on the river’s western bank. If Kharitonov could take the town and hold it, the way would be open for an attack on Kharkov from the south.

Kharitonov’s spearhead ran headlong into the 2nd Regiment of the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) Panzergrenadier Division commanded by SS Standartenführer (Colonel) Theodore Wisch. Wisch’s 1st Battalion, under SS Sturmbannführer (Major) Hugo Kraas, gave the advancing Russians a bloody nose at a small village northeast of Zmiyev. Supported by assault guns, Kraas’s men counterattacked, driving the Soviets back.

Late morning found the Russians launching wave after wave of infantry against the village, but the SS held firm. The Soviets then proceeded to attack up and down the line of Wisch’s regiment. Supported by assault guns, some panzer companies, engineers, and a flak unit, Wisch successfully held his positions while causing heavy casualties to the Soviet 111th Rifle Division.

Holding Slavyansk

Meanwhile, the battle for Slavyansk continued unabated. General Hans Freiherr von Funck’s 7th Panzer Division was charged with holding the town. The division was down to only 35 serviceable tanks as it fought to defend Slavyansk against units of General Nikolai Aleksandrovich Gagen’s 4th Guards Rifle Corps.

Born in 1895, Gagen was a tough no-nonsense commander who had fought in the brutal battles in the winter of 1941-1942 along the Volkhov River. He was determined to drive the Germans out of the town at whatever the cost. Gagen’s 195th Rifle Division had been roughly handled by the 7th Panzer as it tried to fight its way into the eastern part of the town. The Soviet general threw in the 57th Guards Rifle Division in an attempt to take the town from the north and west, but the Germans continued to hold, counterattacking when the situation required it.

Overhead, Red Air Force bombers and ground attack aircraft roamed the skies over the embattled town. German flak batteries tried to drive them away, but the Soviet pilots pressed on, dropping their deadly cargo on von Funck’s position. Red Army artillery also kept up a deadly fire, but the German panzergrenadiers and the engineers of the division were still able to hold the Russians at bay.

Holding Slavyansk helped give other units of the First Panzer Army a chance in their move westward. More of Henrici’s XL Panzer Corps was already arriving in the area to bolster the 7th Panzer. Although General Hermann Balck’s 11th Panzer Division had little more than a dozen tanks, it was a welcome sight to the men of von Funck’s command. Colonel Gerhard Grassman’s 333rd Infantry Division was in similar shape, having been savaged in earlier actions.

Both sides realized the value of the area between Slavyansk and Kramatorsk, where the German defenses ran along the Krivoy Torets River. If the Soviets could force the Germans from their tenuous positions, Vatutin could use Group Popov’s forces to make a deep thrust to the southwest, which would basically cut off the First and Fourth Panzer Armies from the rest of von Manstein’s Heeresgruppe. Accordingly, Vatutin pushed more artillery units into the area to give his troops an added punch.

Henrici’s XL Panzer Corps, weak as it was, defended the area with great skill. Coordinated attacks by the 4th Guards Tank Corps, 3rd Tank Corps, and the 4th Guards Rifle Corps were repulsed again and again. Balck’s 11th Panzer brazenly counterattacked Soviet armor with its few remaining tanks, leaving several T-34s blazing furiously on the battlefield, while the 7th Panzer fended off combined armored-infantry attacks, leaving hundreds of Red Army soldiers dead in the snow.

Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich-Carl von Steinkeller, commanding the 7th Panzer’s 7th Panzergrenadier Regiment, was in the thick of the fighting. Keeping on the move, von Steinkeller went from company to company urging his men to hold firm. An artillery observer followed him, ready to call in fire as the situation demanded. He would later receive the Knight’s Cross, in part for his actions during the battle.

Popov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps, commanded by Pavel Pavlovich Poluboyarov, succeeded in crossing the Krivoy Torets, threatening the rear of the 7th Panzer Division. Henrici immediately ordered Balck’s 11th Panzer Division, supported by a regiment from the 333rd Infantry Division, to counterattack. The Germans were met with the blazing guns of Poluboyarov’s tanks in front and from dug-in antitank weapons firing from the eastern bank of the Krivoy Torets.

Despite the Soviet fire, Balck and his infantry support were able to push the 4th Guards back along the river valley. Russian infantry accompanying Poluboyarov’s tanks panicked and fled, forcing the armor to fend for itself. German sources indicate that 45 Russian tanks were destroyed during the fighting—a significant loss that could only partially be made good by the reinforcements that were trickling in after a grueling journey over extended supply roads.

Vatutin, fed up with the inability of his forces to take Slavyansk and the positions along the Krivoy Torets, reshuffled his units for an all-out assault. Kuznetsov’s First Guards Army was ordered to coordinate with Popov for the attack, while Red Air Force units were given orders to support the operation at all costs.

Underestimating the German Position

The westward movement of German units, as per von Manstein’s plan, had given Vatutin, Golikov, and STAVKA a false sense of optimism. Hitler never conceded territory—every Russian commander knew that. He had shown it by letting his army freeze at the gates of Moscow and the stubborn refusal to retreat from Stalingrad only reinforced that view.

To the Russian mind the retreat of Heeresgruppe Don from the eastern Don Basin could only be viewed as a somewhat panicked rout. The stubborn resistance around Slavyansk was seen as a desperate attempt to save the fleeing German divisions from being overwhelmed by troops of the South West Front and the South Front, and it was assumed that once the Krivoy Torets line was taken the enemy would collapse.

To crack the German defenses Vatutin ordered the First Guards Army to shift south toward the Krasnoarmeiskoya sector, about 60 kilometers southwest of Slavyansk, to threaten the enemy rear. While that move was taking place, the 35th Guards Rifle Division of Gagen’s 4th Guards Rifle Corps forced units of the 333rd Infantry Division out of Lozovaya, a key rail center and supply dump located about 120 kilometers west of Slavyansk. Although the 35th Guards did not press their attack further, taking the town created a dangerous new bulge in the already extended and increasingly confusing lines of battle.

Part of Vatutin’s plan was to use Popov’s 4th Guards Tank and 3rd Tank Corps to smash their way into Slavyansk, paving the way for the 18th and 10th Tank Corps to strike southwest toward Artemovsk. With Slavyansk secured, the 4th Guards Tank and 3rd Tank Corps were to advance to link up with the First Guards Army at Krasnoarmeiskoye. Together, the two tank corps and units of the First Guards Army would then move southeast to Stalino to trap German units retreating from the eastern Don Basin.

As Vatutin prepared his operation, he received new orders from STAVKA. Golikov’s forces were making good progress toward Kharkov and, lulled by the belief that the Germans were indeed in the midst of a massive disorganized withdrawal to the Dniepr, Moscow saw a new chance to bag several enemy divisions in an even bigger pocket than Vatutin had planned.

Vatutin was therefore given the task of setting up blocking forces to prevent an enemy withdrawal to Zaporozhye and Dnepropetrovsk. At the same time, he was ordered to advance southwest to cut off German and Axis forces in the Crimea. The STAVKA plan was overly ambitious by a wide margin, considering that the South West Front had already been in combat for more than two weeks and had received little in the way of supplies or reinforcements.

With Kharitonov’s Sixth Guards Army already supporting Golikov’s drive on Kharkov, it would again fall to Kuznetsov and Popov, along with Lelyushenko’s Third Guards Army, to accomplish this new mission. The First Guards Army would have the dual tasks of taking Slavyansk with Alferov’s Sixth Guards Rifle Corps while other units continued on a westward drive toward Zaporozhye. While this was occurring, Group Popov would make a lightning strike to Krasnoarmeiskoye, taking the town’s rail center and threatening the German rear.

Both Kuznetsov and Popov had voiced doubts about Vatutin’s earlier proposal. Their units had been manhandled by the Germans, and losses in men and equipment had still not been made good. The two Soviet generals had even graver doubts about the new plan. Supplying their forces as they moved south and west would be a nightmare with the existing supply line, which was already stretched to the limit.

Popov, in making his dash to the south, would have a total of about 180 tanks spread between his four tank corps. He had enough fuel for one refueling and ammunition for two resupplies. The infantry units in his command were in even worse shape. Despite STAVKA’s assertions that the Germans were on the run, the field commanders had a more cautious view of the situation.

Vatutin brushed aside his commanders’ doubts. These were orders from Moscow and had to be obeyed. The consequences of disobedience were well known, and no Soviet general in his right mind would think about going against the Kremlin at this stage of the war.

A Bold Penetration

Poluboyarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps was chosen to spearhead the new attack. In the early hours of February 11, the Soviet armor began its 85 kilometer charge to Krasnoarmeiskoye. Led by the 14th Guards Tank Brigade, Polubarov’s forces cut through the German defenses and moved quickly down the one good road in the area. Following fast on the heels of the 14th were the 3rd Guards Mechanized Brigade, the 7th Ski Brigade, the 9th Guards Tank Brigade, and other corps units.

The deep thrust caught the Germans off guard, and by mid-morning the 14th Guards Tank Brigade had taken Krasnoarmeiskoye. With the town secured, the victorious Soviet troops helped themselves to the supplies left in a supply dump by the retreating enemy. The loot, especially the fuel and rations, was a welcome sight to the exhausted Russians.

Another important benefit, not readily apparent to the troops at the scene, was the severing of a vital German supply and communications line. With the capture of Krasnoarmeiskoye, the important Dnepropetrovsk-Mariupol rail line was rendered useless, leaving units of the First Panzer Army and Army Abteilung Hollidt in dire straits.

Group Popov’s dramatic march to Krasnoarmeiskoye threw German plans for defending the western Don Basin into disorder. The defense of Slavyansk was now in jeopardy due to the Soviet units to the south and west of the position. Von Mackensen was also in the midst of planning an attack to recapture Kramatorsk, but that too had to be put on hold in light of Popov’s success.

“Contain the Popov Tank Group”

Realizing the precarious position of the German troops holding the river lines to the east of Krasnoarmeiskoye, von Mackensen called upon the 5th SS Panzergrenadier Division Wiking. Commanded by SS Gruppenführer (Major General) Felix Steiner, the Wiking was a multinational division made up of Germans, Norwegians, Danes, Swiss, Finns, Walloons, and Estonians. It had just arrived in the Don Basin after an arduous retreat from the Caucasus, and its troops were exhausted.

As elements of the division were just passing through Stalino, Steiner received the following message: “PanzerArmy H.Q. to Division Wiking Urgent! Powerful enemy forces, Popov Tank Group, across the Donets near Izyum advancing southward toward Krasnoarmeiskoye. Wiking Division to immediately turn to the west. Attack toward Krasnoarmeiskoye. Contain the Popov Tank Group. (signed) von Mackensen”

Steiner immediately ordered his division to halt. His original orders were to head north from Stalino to the Konstantinovka area, and the advance units of his Germania Regiment were already headed in that direction. With his chief of staff, Steiner hastily issued new orders. Artillery was regrouped, and the Nordland Regiment was ordered to take the lead in the new westward advance while Germania turned its units around. The division’s Westland Regiment was also readied to join in the mad race to stop the Soviets.

With Nordland’s reconnaissance platoon leading the way, the regiment hastened toward Krasnoarmeiskoye. By the end of the day, the advance guard under SS Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Wolfgang Joerchel had overpowered weak Russian forward positions and taken Hill 180, which overlooked the entire Krasnoarmeiskoye sector. Joerchel quickly sent for other battalions of the regiment, which deployed south and west of the town to contain any further Soviet expansion in those directions.

Much of Group Popov was spread out along the road from Kramatorsk to Krasnoarmeiskoye in defensive positions. Von Mackensen realized that Wiking did not have the capability to contain and destroy the Red Army units along the entire length of the road, so he issued new orders to other divisions of his command.

The occupation of Slavyansk was still of utmost importance. Shuffling his forces, von Mackensen ordered two regiments of the 333rd Infantry Division to make a forced march toward Krasnoarmeiskoye. As the weary infantry slogged toward its new goal, the 7th Panzer and 11th Panzer, which were fighting in the areas around Slavyansk and east of the Krivoy Torets River, were ordered to turn their units westward. The 3rd Panzer Division was ordered to extend its line to take over the defensive positions of the two departing divisions. Von Mackensen planned to use the two divisions to strike at Group Popov’s extended supply line while Wiking and the two regiments of the 333rd kept up the pressure at Krasnoarmeiskoye.

The movements of the German divisions to their assembly areas were surprisingly fast, and the attack on the supply line began in the early hours of February 12. Soviet defense positions had been set up in each village along the supply road from Kramatorsk, and several strong antitank companies had been brought forward to reinforce the village bastions.

“Assistance urgently required. Long live Stalin!”

At Krasnoarmeiskoye Steiner planned to use the Germania to flank the town from the west. Supported by the two regiments of the 333rd, Germania was ordered to take the village of Grischino, northwest of the town. While the other Wiking regiments assaulted Krasnoarmeiskoye from the south, elements of von Funck’s 7th Panzer would attack from the east and secure the town’s northern flank.

Polubayarov, knowing his precarious position, had kept the units of his 4th Guards Tank Corps on high alert. Each subordinate commander was told to be ready for a German counterattack, and orders were given down to company level to fortify lines of approach that could be used by the enemy. Each soldier was to make the Germans pay for every meter of land, every house, and every hill that the Red Army had recently liberated on its valiant march to Krasmoarmeiskoye.

SS Standartenführer (Colonel) Jürgen Wagner commanded the Germania Regiment. His men stormed forward into a withering fire from the Soviet positions as they began the assault. Rifle and machine gun bullets slapped around them like angry bees, while tank and antitank shells tore into their ranks. Grenadiers fell, their blood turning the churned up snow a bright crimson, but Wagner continued to urge his men to attack.

The artillery commander of the Wiking, SS Oberführer (Senior Colonel) Herbert-Otto Gille, deftly moved his artillery battalions closer to support the attacks on Krasnoarmeiskoye and Grischino. Supported by flak units, Gille’s artillery smashed one Soviet position after another, giving the Germans a chance to rush forward.

Wagner swung his regiment around Grischino and finally broke into the northern edge of the town. At the South West Front headquarters a frantic radio message, which must have been garbled in transmission, was received from the Russian commander defending Grischino. “Have been attacked by 5 SS Panzer Divisions, can only hold out with difficulty. Assistance urgently required. Long live Stalin!”

Once inside the town, Wagner’s men found themselves bogged down in house-to-house fighting. It was the same for the other Wiking regiments at Krasnoarmeiskoye. In the close fighting, Gille’s artillery was of little use. The lines were too close, and the Soviets used every house as a strongpoint. For the time being the battle for both towns was a stalemate.

The 88s of Rovny

North of Krasnoaremiskoye elements of the 7th and 11th Panzer Divisions drove westward in a forced march. The Germans ran headlong into the 10th Tank Corps and the 41st Guards Rifle Division. Heavy defensive fire from the Russians forced the panzers to slow and finally stop their attack. Seeing that the Soviets could not be broken, the divisions turned toward Kramatorsk to prepare for a new attack on that town.

At Grischino and Krasnoarmeiskoye the battle continued unabated. Wiking had now been joined by the two regiments of the 333rd, and Gille’s artillery was hammering the Russian rear areas. In addition, the Soviets were now running short of supplies.

Although Henrici’s XL Panzer Corps had its various units involved in several actions stretching from Kramatorsk to Krasnoarmeiskoye, he still had the opportunity to disrupt the supply line to the 4th Guards Tank Corps. Armored reconnaissance companies fought running battles with Soviet supply columns trying to make their way south, and the roads were soon littered with flaming trucks. The hit-and-run tactics of the Germans struck as the Russians were spread out in single file and usually ended with the destruction of most of the supplies.

Poluboyarov, growing desperate, ordered the 9th Independent Guards Tank Brigade to try and breach the closing ring around Krasnoarmeiskoye. The 9th hit the Westland Regiment north of Krasnoarmeiskoye near the village of Rovny. More than a dozen tanks with mounted infantry pierced the German line and made a push toward the center of the village.

The regimental commander, SS Sturmbannführer Erwin Reichel, had just taken over after SS Sturmbannführer Harry Polewacz was killed in combat. Reichel ordered a battery of 88mm guns supported by Panzergrenadiers into the center of Rovny as the Soviets approached. When the Russians reached the interior of the village, the 88s destroyed almost all of the tanks. The stunned Russian survivors fled, leaving 12 blazing hulks and dozens of dead behind.

“Throw Everything in”

Vatutin was not about to give up on Group Popov. Gathering all available reserves, the Soviet general sent them to reinforce the spearhead at Krasnoarmeiskoye. When word was received that Russian reinforcements were headed south, new orders were sent to the scattered German forces of the First Panzer Army. The Wiking and the 11th Panzer Division were told to halt their attacks on February 14 and attempt to pin down the Russian forces at Krasnoarmeiskoye and Kramatorsk. Meanwhile, the battle to hold the Slavyansk area would continue. Von Mackensen also ordered Henrici to use whatever resources necessary to keep pressure on the supply columns following the reinforcements heading toward Poluboyarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps.

Henrici angrily replied to the order, “What am I supposed to use? My men are stretched to the limit already.”

“Just do it,” von Mackensen replied. “Throw everything in. I don’t care how you do it—just get it done!”

While things were strained in the First Panzer Army, the situation around Kharkov was at a critical stage. By February 10, Golikov’s 40th and 69th Armies were battling on the outskirts of the city, with the recently arrived II SS Panzer Corps putting up fierce resistance. Bitter fighting raged for the next five days, and Hitler personally intervened, ordering the corps commander, SS Obergruppenführer (Lieutenant General) Paul Hausser, to hold the city at all costs.

Infuriated at what amounted to a death sentence for his men, Hausser disregarded the order and pulled his SS divisions out of Kharkov, forcing other defending German units to disengage as well. On February 16, Golikov reported to Moscow that Kharkov was once again in Soviet hands.

A Quartermaster’s Nightmare

Logistically, both sides were facing a quartermaster’s nightmare and both the German and Soviet commanders were in dire straits. With Kharkov gone and the Russians occupying Grischino and Krasnoarmeiskoye, the only supply line open to the First Panzer Army and Army Abteilung Hollidt was the railway that ran through Zaporozhye. The task of supplying German units by this route was hampered by the fact that a main bridge spanning the Dniepr River, destroyed during the 1941 Soviet retreat, had not yet reopened. Supplies had to be unloaded from trains and reloaded to trucks and wagons before making their way farther eastward.

Group Popov was in a similar situation. Reinforcements were trickling in to the 4th Guards Tank Corps but supplies were a different matter. Von Mackensen’s orders to Henrici were being carried out by ad hoc units and units taken away from their parent regiments. Although the Soviet armored columns came under some fire as they strove to reach Krasnoarmeiskoye, the supply formations continued to bear the brunt of the German attacks.

Some good news came to Vatutin on February 16 when the rest of the 7th Panzer Division, finally ordered to give up its defense of Slavyansk, pulled out and headed toward Krasnoarmeiskoye. Units of the First Guards Army finally were able to occupy the entire town, but the victorious Soviets were in no condition to pursue the 7th. The 3rd Panzer Division quickly lengthened its lines to cover the 7th as it raced southwest to join elements of the division already engaging Gagen’s 4th Tank Corps.

Von Manstein’s Plan to Take Kharkov

On February 17, Hitler flew to meet von Manstein at Zaporozhye. Not one to mince words, von Manstein laid out the situation as follows: “Army Abteilung Hollidt had just occupied the Mius River Line, followed closely by the South Front. For the time being, the line could be effectively defended.”

The First Panzer Army had halted the Soviets at Grischino and Krasmoarmeiskoye, but the issue there had still not been decided. Von Mackensen’s panzer army was also still involved in heavy fighting at Kramotorsk, Lisichansk, and the Slavyansk area, with the issue in all three sectors still in doubt. The forces retreating from Kharkov, now gathered under Army Abteilung Kempf, were withdrawing southwest toward Poltava and the Mozh River.

At first, Hitler refused to believe the seriousness of the situation. Already furious at the loss of Stalingrad, and then Kharkov, he could not believe that the Soviets still had the men and equipment to carry out another operation that could threaten the entire southern wing of his eastern armies. Von Manstein let him rant for a while before submitting a plan to save his threatened Heeresgruppe.

Von Manstein played his hand masterfully, laying out his formula to retake Kharkov. At the mention of recapturing the city, Hitler immediately calmed down and began to listen intently.

Kharkov could only be taken if the southern flank of the Heeresgruppe was secure, so von Manstein proposed consolidating Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps into one striking force, taking it away from the Kharkov sector and sending it southeast toward Pavlograd. This action would prevent any further Russian advance on Dnepropetrovsk.

At the same time, Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army, which had made the bitter retreat from the Caucasus, would concentrate its units west of Zaporozhye. Together, the two forces would strike the elements of the First Guards Army and the Sixth Army that were advancing toward the vital Dniepr crossings while the First Panzer Army would once again take on Group Popov.

Throughout his briefing, von Manstein continuously played on the premise that the one condition necessary to retake Kharkov was the survival of the First Panzer Army and Army Abteilung Hollidt. When the Soviet threat in the southern Don Basin was eliminated, the Kharkov operation could begin.

Hitler Concedes Operational Control to Von Manstein

Although Hitler was swayed by von Manstein’s argument, he was not totally convinced of the plan. The following day, February 18, he again met with von Manstein to discuss the operation. Von Manstein was essentially calling for freedom to maneuver without micromanagement from Hitler or Berlin.

In another heated exchange, Hitler once again voiced his opinion that, although the number of Soviet units facing von Manstein looked impressive on paper, they were really burned-out shells of what were once divisions and brigades. Although he was partially correct, the armies that had taken Stalingrad were already on the move and the threat of the South Front bursting through Army Abteilung Hollidt’s Mius River line would more than overpower the existing German forces in the southern Don Basin.

In the midst of the meeting, von Manstein received reports that units of the First Guards Army had taken Pavlograd and Novomosskovsk, bringing the Soviets to within 20 kilometers of Dnepropetrovsk. Army Abteilung Hollidt also reported several small enemy penetrations along its Mius River defenses. The report also indicated that the Russians were consolidating around Kharkov while sending spearheads farther westward.

A report from Krasnoarmeiskoye indicated that the newly arrived elements of the 7th Panzer Division were trying to break the 4th Guards Tank Corps. Overcoming fierce resistance from the 14th Guards Tank Brigade, units of the 7th succeeded in taking the town center before being stopped by a Russian counterattack. On the western side of the town the Wiking Division ran headlong into defenses set up by the 12th Guards Tank Brigade and was immediately stalled by heavy defensive fire.

Von Manstein used these developments to hammer home his ideas for destroying the Soviet incursion in the Don Basin. He pointed out that once the muddy season arrived operations at the front would grind to a halt and the Russians could use their rail lines to resupply and reinforce their divisions holding positions deep inside the German lines.

With their men and materiél built up once more, the southern German forces would be in even greater danger of being pinned against the Sea of Azov, and Kharkov would be virtually untouchable. The next day, Hitler suddenly gave von Manstein what amounted to a carte blanche for operations in southern Russia and then climbed aboard his transport plane and left.

Krasnoarmeiskoye Falls to the Germans

The German field marshal wasted no time in implementing his plan. Krasnoarmeiskoye was hit hard by the 333rd Infantry Division and the Wiking Division, while the 7th Panzer Division swung north of the town. Poluboyarov’s units in the town were now caught in a vise that could only be loosened by attacks from the outside. Popov had already ordered his 3rd Tank Corps to relieve the embattled forces in the town as quickly as possible, but that attempt was soon thwarted.

While the 3rd Tank Corps was racing south, Balck’s 11th Panzer Division moved into blocking positions south of Kramatorsk near the village of Gavrilovka. As the 3rd Tank Corps sped toward Krasnoarmeiskoye its flank was shattered by a full-scale attack from Balck’s division. Burning Soviet tanks littered the landscape as the Russians desperately tried to regroup to meet the attack, but Balck’s men had already achieved their objective of halting the rescue attempt.

By the end of the day, Krasmoarmeiskoye was all but in German hands, Grischino had fallen, and Poluboyarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps was nothing more than a skeleton of a unit with almost all of its tanks destroyed. Leaving the 333rd to mop up Poluboyarov’s corps, von Manstein ordered the Wiking to join the 7th Panzer and head north toward the leading elements of Group Popov’s 10th Tank Corps, which had moved into defensive positions around the town of Dobropolye.

February 20 was the final day for the Russian forces inside Krasnoarmeiskoye. Down to only 12 tanks, the Soviets could do little against the pressure brought to bear by the 333rd. In small groups, some of the Red Army soldiers were able to break through gaps in the German line and head north toward the 13th Guards Tank Brigade, which was guarding the area around Barvenkovo.

STAVKA’s Strategic Stubbornness

STAVKA’s plan was falling apart, but no one seemed to want to face that reality. Krasnoarmeiskoye was once again in German hands, and the First Panzer Army was hammering away at the Soviet units stretched out on the road south of Kramatorsk. In the north, von Manstein had sent Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps to link up with General Otto von Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, which was part of the Fourth Panzer Army. Together, the two corps struck the Sixth Army near Krasnograd.

In the air, Field Marshal Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen’s Luftflotte 4 hit the Soviets with about 1,000 sorties that precluded any attempt by the Russians to form a coherent defense. The increasingly frantic calls from his commanders prompted Popov to ask Vatutin for permission to withdraw his forces. The request was forcefully denied.

Despite the troubling news coming from the Don Basin, Stalin and his general staff still believed they were on the verge of a great victory. New intelligence reports concerning German concentrations were ignored by STAVKA, which was still in a state of euphoria after the victory at Stalingrad. The unrealistic goals set for the Don Basin offensive were part of that euphoria, and it was now costing the Red Army dearly.

By February 21, it was clear to the Germans that the Soviets had been caught flat footed. Fretter Pico’s XXX Army Corps moved toward Stalino, while von Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII and General Friedrich Kirchner’s LVII Panzer Corps advanced on Pavlograd and Lozovaya. Soviet forces around Pavlograd were also under pressure from the II SS Panzer Corps, Corps Raus, and elements of the Fourth Panzer Army. As long as Army Abteilung Hollidt vigorously defended the Mius River line, Vatutin’s forces were going to be in a great deal of trouble.

On February 22, oblivious to the real situation, STAVKA ordered Kharitonov’s Sixth Army and the Voronezh Front’s Third Tank Army even farther westward. They were met head on by the full power of Hausser’s panzers, which smashed Khartinov’s center and right wing. Despite the pounding he was taking, Kharitonov ordered his mobile reserves into the battle in a futile attempt to follow the orders from Moscow.

Meanwhile, Group Popov was reeling under the attacks from Henrici’s XL Panzer Corps. Desperate for supplies, the Russians no longer had the fuel and ammunition to hold out against the German armored and infantry units. Air supply was tried by the Red Air Force, but von Richthofen’s fighters shot the transport aircraft out of the sky at an alarming rate.

Khartinov’s Sixth Army was in no better shape. His 25th Tank Corps, which had been ordered to advance in front of the main army, was stretched out almost 100 kilometers to the west when the Germans struck. On February 23, Khartinov was hit on both flanks by the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Division Das Reich and the Sixth Panzer Division. Pounded by the Luftwaffe as well, the 25th Tank Corps disintegrated, its surviving personnel abandoning their equipment and fleeing toward the northeast.

By now, even STAVKA started to notice that something was going very wrong. Reports coming from Popov and Kharitonov painted a picture of panic among their troops, and their commanders begged for something to be done before they were all annihilated.

With his Sixth Army almost in ruins, Vatutin sent a rifle corps from the First Guards Army to support Kharitonov. To the north, Golikov, sensing the impending danger to his left flank, ordered his 69th and Third Tank Armies to swing southward to add to that support, but it was already too late to stop the German momentum.

A Bloody Red Defeat

On February 24, von Manstein sent the II SS Panzer Corps toward Pavlograd. The attack rolled over the 1st Guards Tank Corps and the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps, which had been sent to defend the town. They were Vatutin’s last reserves. After a sharp battle, SS forces occupied the town and went on to pursue the fleeing Russians, who had left most of their equipment behind.

Now fully aware of the consequences of the German attacks, Vatutin ordered the Sixth Army to take a defensive posture. The sad truth was that Khartinov had little resources left with which to defend his sector. With Hausser’s divisions surging forward, most of the Sixth Army was already in full flight.

During the next two days the units of the First Panzer and Fourth Panzer Armies retook much of the land lost in the early days of February. By February 27, Group Popov had all but been destroyed and the Sixth Army was on the verge of disintegration. The First Guards Army had also suffered heavily under continued German attacks.

It was now painfully clear to Moscow that Operation Gallop was finished. Orders were sent to the remnants of the Sixth Army and the First Guards Army to withdraw and set up new lines on the Northern Donets River. Any thoughts of renewing the attack in the near future were shattered in the first days of March, when the II SS Panzer Corps essentially destroyed the Third Tank Army.

The combination of Soviet ambition and von Manstein’s brilliant handling of the battle culminated in a bloody defeat for the Red Army. The stage was now set for one of von Manstein’s greatest accomplishments—the recapture of Kharkov—which would take place in mid-March.

That achievement has largely overshadowed the desperate February struggle for the Lower Don Basin. However, without the defeat of the Red Army on the Donets-Dniepr battlefield, the German reoccupation of Kharkov would probably never have been possible.

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front and has contributed numerous articles on the subject to WWII History. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments