By Victor Kamenir

The old Imperial capital of Hue was ready for the Tet Festival, a joyous occasion celebrating the Vietnamese Lunar New Year on January 31, 1968. It was the time when families came together to greet the new year in hopes it would bring them better fortunes than the previous one. The streets and homes were decorated with colorful strings, lanterns, and arrangements of golden apricot and peach blossoms and flowers. Honoring the upcoming festival, the president of South Vietnam, Nguyen Van Thieu declared a cease-fire.

The capital of the Thua Thien Hue Province and a revered symbol of Vietnam’s past, Hue was treated almost as a free city by both the South Vietnamese government and the Communist Viet Cong guerillas. Other than an occasional mortar shell or a rocket lobbed into the city by Viet Cong, Hue was largely spared the ravages of war.

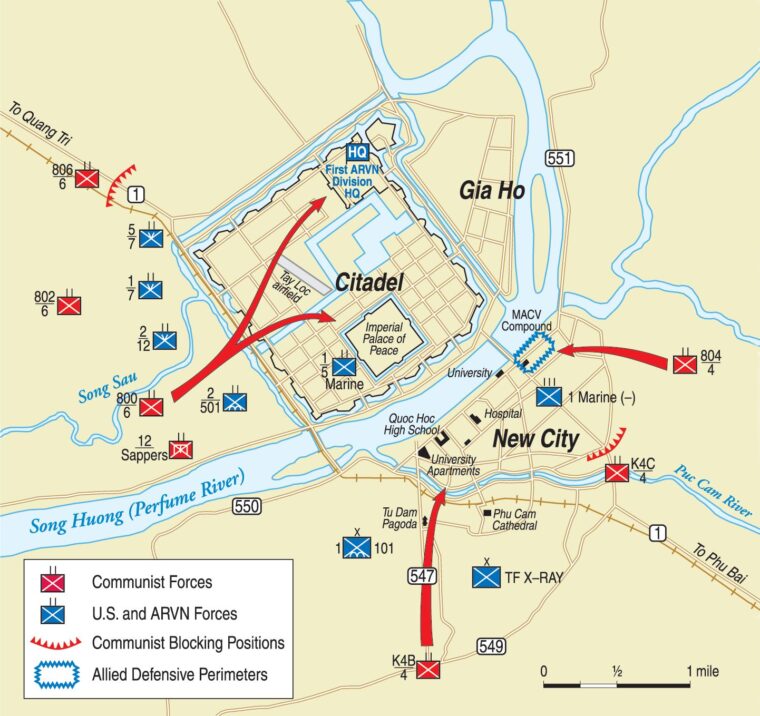

The third largest city in Vietnam with a population of 140,000, Hue lies on the bank of the Perfume River. On the river’s north bank was the older part of the city, known as the Citadel, a three-square mile rectangular enclosure inside stone walls up to 30 feet tall. A water-filled moat up to 90 feet wide and up to 12 feet deep ran along the Citadel’s walls.

Inside the Citadel was the old Imperial Palace, complete with its own walls. Parks, residential and commercial blocks, often with their own stone enclosures, and a small Tay Loc Airfield filled the rest of the Citadel. Along the waterfront of the Perfume River’s southern bank was the city’s administrative heart, containing provincial headquarters, prison, treasury building, and Hue University. The Nguyen Hoang Bridge, spanning the river, connected both parts of the city. The river, the An Cuu Canal, and Highway 1 formed an area that became known as the Triangle.

The Allied presence in the city was minimal. In the northeast corner of the Citadel was the Mang Ca compound, housing the headquarters of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN)’s 1st Infantry Division. Four battalions of the division’s 3rd Infantry Regiment and two airborne battalions from the General Reserve occupied camps within several miles of Hue. The 7th Cavalry Squadron was at Tam Thai Camp on the city’s southern outskirts. Division’s commander Brig. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong was considered one of the best South Vietnamese commanders by the Americans. Truong had only his elite reconnaissance company Hac Bao (Black Panthers), and an ordnance company at the Tay Loc Airfield at his immediate disposal in the city.

Two blocks south of the Nguyen Hoang Bridge was the compound of the United States Military Assistance Command—Vietnam (MACV). It housed close to 200 U.S. Army and U.S. Marine personnel under command of U.S. Army Colonel George Adkisson. American and Australian officers, assigned in adviser and observer capacity to South Vietnamese units, billeted there for a few days before heading back out to the field. The compound consisted of a former hotel and several adjoining buildings encircled by fences and barbed wire and protected by bunkers and guard towers. At the bridge’s southern end was a small U.S. Navy landing dock abutted by a park.

The Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) began planning the Tet Offensive almost a year in advance. The objective was to attack all major cities and strategic locations in South Vietnam to incite a popular uprising that would bring down the corrupt government of South Vietnam. The operation was called the Tong-Tan-cong-Noi-day (General Offensive or General Uprising).

Since September 1967, PAVN and Viet Cong guerrillas had been launching strong attacks south of the Demilitarized Zone. Unlike previous small-scale strikes, the new attacks involved company and battalion-sized units. Despite suffering heavy casualties, Communist actions accomplished their missions of drawing American and South Vietnamese attention toward the border region. In response, the commander of the U.S. forces in Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, began shifting U.S. Marine and Army units north.

Task Force X-Ray was established at Phu Bai, six miles south of Hue, under Brig. Gen. Foster “Frosty” LaHue, assistant division commander of the 1st Marine Division, as part of the realignment. The 1st and 5th Marine Regiments and the 1st Artillery Group of two battalions were placed under LaHue’s command. As January 31 approached, only the Task Force headquarters and headquarters of the two regiments moved to Phu Bai. Other than one infantry company as a reaction force, the rest of LaHue’s combat units were in the field.

The Viet Cong guerillas had been infiltrating Hue, stockpiling ammunition, food, and supplies. They primarily used young women, some of them in their teens, which drew less attention. The girls observed the movements of the ARVN and American forces, guard shifts, and the number of guards. They identified home and work addresses, routines of the Europeans, government officials, military and police officers, and anyone whom the Viet Cong considered supporters of the government.

At the same time, well-trained and well-equipped regular PAVN units have been moving south on a long, dangerous journey along the Ho Chi Minh trail. Some of the early-arriving units spent many months in the clandestine mountain camps. To coordinate operations of the PAVN regulars and Viet Cong guerillas, numbering close to 8,000 men, the Hue City Front was created under the command of PAVN officers.

Despite PAVN’s best efforts, movements of large numbers of men and supplies were impossible to hide completely. Increased enemy contacts and worrisome intelligence reports led President Thieu to cancel the cease-fire. Similarly, General Truong issued a recall order in Hue for his men to rejoin their units, but the overwhelming majority had already left for the holiday. Truong deployed platoons of Hac Bao at strategic locations throughout the city, including the Tay Loc Airfield.

Before dawn on January 31, over 80,000 PAVN and Viet Cong troops attacked over 70 locations throughout South Vietnam. At Hue, a signal flare at 2:30 a.m. launched the attack. Under cover of mortar and rocket barrage, PAVN battalions in their clean new green uniforms and Viet Cong in black rushed toward Hue. The main attack came from the southwest while the Communist guerrillas, already in the city, attacked the ARVN and police detachments guarding the gates from the inside.

The 800th and 802nd Battalions from the 6th PAVN Regiment and the 12th Viet Cong Sapper Battalion attacked through the southwestern gates toward the Mang Ca compound and the Tay Loc Airfield. A detachment of PAVN breached the compound, but after heavy fighting General Truong’s scratch force of roughly 200 staff and support personnel threw back the attackers.

At the Tay Loc Airfield, the ARVN ordnance company and the Hac Bao platoon put up a dogged resistance and hung onto several buildings, although all aircraft were destroyed. As the situation at the airfield stabilized, General Truong recalled the Hac Bao platoons to reinforce the Mang Ca compound. At the same time, he radioed all units outside Hue to rush to the city. Next, Truong contacted his immediate superior, Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam, commander of the ARVN 1st Corps, requesting additional units. Lam concurred and placed the 2nd and 7th Airborne battalions under Truong’s command.

During the attack several of the PAVN units, made up of northerners and unfamiliar with Hue, became separated and veered off course moving through the city. When the local guide leading the 806th Battalion was killed, the battalion lost its way and did not add its weight to the attack on Mang Ca. Squad and platoon-sized detachments were left to guard important locations and street intersections, further fragmenting PAVN forces.

Two battalions from the 4th PAVN Regiment (804th, 815th, and 818th) and the Hue City Sapper Battalion moved against the Triangle and outlying southern and eastern suburbs. However, only the 804th Battalion arrived on time, another battalion was delayed taking a local defense outpost, and the third became lost.

As the 804th PAVN Battalion attacked the MACV compound, an alert Marine in a guard tower spotted them and opened fire with an M-60 machine gun. The Americans inside the compound quickly occupied bunkers and defensive positions and hurled back two attacks. Failing to take the compound by storm, the Vietnamese continued harassing fire with mortars, B40 rockets, and machine guns.

Except for the MACV and Mang Ca compounds, by daylight, Communist forces controlled most of the city, including the Imperial Palace, the province headquarters, and other governmental buildings. They held 11 out of 12 city gates, with only the gate closest to Mang Ca remaining in General Truong’s hands. A blue and red flag with a yellow star, a combination of the Viet Cong and North Vietnam’s flags, flew from the flagpole near the Imperial Palace.

Political officers began rounding up foreigners and the South Vietnamese “traitors” from prepared lists. Some were offered an opportunity to join, others were taken away never to be seen again, several Europeans and Americans among them. To the dismay of political officers, the city’s population remained largely apathetic to “liberation.” Many residents were put to work digging trenches, building bunkers, and carrying supplies.

In the village of Thon La Chu, three miles west of Hue, the Hue City Front established its headquarters in a three-story underground bunker. Built by a South Vietnamese official, who turned out to be a Communist sympathizer, the bunker was meant to be a bomb shelter, but all along intended to serve as the command post for the Front.

Due to initial poor communications between the PAVN units, the Front’s command was unaware that Nguyen Hoang and An Cuu bridges remained standing after detachments sent to destroy them were wiped out by local forces.

Alerted by General Truong, several ARVN units attempted to reach Hue. Two airborne battalions and a troop from the 7th Armored Squadron moved toward the city from the PK-17 outpost north of the city. They ran into heavy PAVN resistance and were forced to halt after taking casualties. The next day a patrol from Hac Bao led them around the Citadel from the north to the Mang Ca compound.

South of the city, the rest of the 7th Armored Squadron, composed of American light M24 Chafee tanks and M113 Armored Personnel Carriers, minus the troop at PK-17, moved off from their Tam Thai camp. Just short of the An Cuu Bridge it ran into a PAVN ambush. Losing several tanks and APCs, and its commander killed, the rest of the squadron retreated several miles along Highway 1.

The 2nd and 3rd battalions from General Truong’s 3rd Regiment encountered heavy enemy resistance and halted southwest of the city. The 1st and 4th battalions, moving from the southeast, were surrounded. The 1st Battalion managed to break through to the coast and reached the Citadel the following day. The 4th Battalion was not able to extricate itself for several days.

While the fighting was raging at the MACV compound, Colonel Adkisson radioed Task Force X-Ray for help. General LaHue dispatched the only available unit, Company A under Captain Gordon Batcheller, 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment (1/1st) to relieve the MACV compound. The Marines moved off on trucks, accompanied by two U.S. Army M42 “Duster” self-propelled guns armed with twin 40mm cannons and two trucks with M45 “Quadmounts” armed with four .50-cal machine guns.

South of the city, Company A encountered four Marine M48 Patton tanks (two armed with 90mm cannons and two flamethrower “Zippo” tanks) from the 3rd Marine Tank Battalion. The tanks were heading to the U.S. Navy dock in Hue for embarkation to move north to Dong Ha. The tankers halted upon encountering destroyed tanks and APCs from ARVN’s 7th Cavalry Squadron. After a short discussion with Captain Batcheller, the four tanks led the way to Hue.

As the small column approached the city, it encountered increasing enemy resistance before forcing its way across the An Cuu Bridge under fire from automatic weapons, RPGs, and 40mm rockets. Casualties were heavy, including Captain Batcheller seriously wounded, and the depleted company took up defensive positions.

Shortly after noon, General LaHue sent Lt. Col. Marcus Gravel, commander of the 1/1st Marines, with just-arrived Company G under Captain Meadows, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, (2/5th) to follow Company A. After reaching Batcheller’s company and taking fire along the way, Gravel consolidated the two companies. Sending the dead and wounded back to Phu Bai on trucks and led by the four tanks, Gravel’s column reached the beleaguered MACV compound around 3 p.m.

After Gravel reached the compound, General LaHue, unaware of the actual situation in Hue, ordered Gravel to move to the Citadel to reach General Truong’s compound. Company A, down to half its strength, was in no shape to advance. It expanded the defensive perimeter to the south side of the Nguyen Hoang Bridge and secured the Navy dock.

Marine M48 tanks were too heavy to cross the bridge and remained on the south side to provide fire support. Company G moved across the bridge on foot under withering automatic weapons fire from the Citadel. Two platoons reached the narrow strip of land between the bridge and the Citadel wall but were pinned down and could advance no further. With darkness fast approaching and casualties mounting, Gravel issued withdrawal orders. Taking their dead and wounded with them, Company G re-crossed the bridge, losing a third of the company.

During the night, a Marine CH-46 helicopter landed under fire in the park near the Navy dock to drop off ammunition and evacuate casualties.

On February 1, Lieutenant General Hoang Xuan Lam and Lt. Gen. Robert Cushman, commander of the III Marine Expeditionary Force, met at Da Nang. The two generals decided to have ARVN forces liberate the north of the river, while the Marines took the south. Because of the city’s historical significance, they chose to refrain from using heavy weapons, artillery, and air strikes to limit damage to the city.

Still unaware of the situation in Hue, General LaHue ordered Gravel to reach the prison, seven blocks west of the MACV compound, where a small group of ARVN defenders still held out. After futile protests, Gravel sent out Captain Meadows’ Company G, led by Patton tanks. As soon as Company G left the compound, they came under heavy machine gun fire. The PAVN turned every building into a defensive position, sweeping the streets with withering automatic weapons fire. Marines were proficient in fighting in Vietnam’s jungles and rice paddies, but street fighting was a whole new experience. Until they found city maps at a Texaco station, Marine officers unfamiliar with the city had only foggy notions on how to proceed to their targets. Eventually, after three hours of fighting, Meadows’ Marines captured the Hue University building but could not proceed further.

Company F, 2/5th Marines under Captain Michael Downs, arrived in the morning by helicopters. Gravel immediately gave Downs a mission to rescue a detachment of U.S. Army and Air Force technicians unnoticed by the enemy at the communications center several blocks from the compound. A platoon sent out by Downs was ambushed and forced to turn back, bringing their dead and wounded with them.

Truong’s two airborne battalions recaptured the Tay Loc Airfield in the Citadel, where the ordnance company still defended several buildings. The 1st Battalion, 3rd ARVN Regiment, reached Mang Ca, while Marine helicopters delivered two companies from the 4th Battalion, 2nd ARVN Regiment, under heavy fire. Inclement weather and falling darkness prevented the delivery of the rest of the battalion. By the end of the day, General Truong’s troops cleared the northwest corner of the Citadel.

Due to still-poor communications between the Hue City Front units, its command was unaware that the An Cuu Bridge on the canal still stood. It allowed Task Force X-Ray to bring up reinforcements and supplies from Phu Bai and evacuate casualties. One convoy brought the Company H, 2/5th Marines under Captain Ronald Christmas, accompanied by two M-50 Ontos. The Ontos (Greek for “thing”) lightly armored tracked vehicle mounted six 106mm recoilless rifles, four .50 spotting rifles, and a .30 caliber machine gun.

Commander of the 2/5th Marines, Lieutenant Colonel Ernest Cheatham, and Col. Stanley Hughes, commander of the 1st Marine Regiment, were to follow the next day, bringing Company B, 1/1st Marines. Aware of his lack of knowledge of urban combat, Cheatham located two field manuals, Combat in Built-Up Areas and Assault on a Fortified Position. The main lesson Cheatham learned was to stay off the streets as much as possible and to move through walls by blowing holes in them. To that end, he rounded up all the available bazookas at Phu Bai and six 106mm recoilless rifles, the same type mounted on Ontos.

On February 3, Hughes and Cheatham arrived at the MACV compound, bringing replacements and volunteers from Phu Bai. Upon arrival, Hughes assumed control from Gravel. Cheatham now had three companies of his battalion, the fourth was still in the field, and Gravel had one company from his battalion, Company A, with Company B arriving the next day. With his three companies, Cheatham would attack west with the Hue University as his base of operations. Company A, severely mauled two days before, was to expand the perimeter around the dock and clear approaches to Highway 1.

As the American and ARVN presence in Hue steadily increased, the Hue City Front headquarters in Thon La Chu ensured a steady flow of reinforcements and supplies reaching the PAVN units in the city. Per General Cushman’s request, General Westmoreland ordered the commander of the U.S. Army 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), Maj. Gen. John Tolson to cut the enemy lines of communications. Tolson delegated the mission to Colonel Hubert Campbell, the division’s 3rd Brigade commander.

The brigade’s artillery at Camp Evans, 24 miles north of Hue, was too far to support the attack. At the same time, heavy enemy air defense prevented helicopter insertion in the immediate vicinity of Hue. On February 2, helicopters brought the 2nd Squadron, 12th Cavalry (2/12th) under Lt. Col. Richard Sweet to PK-17, seven miles north of Hue, from where the troopers would advance on foot.

The following day, February 3, the 400 men of the 2/12th moved off in heavy rain without artillery support. Sweet decided to make a sweeping maneuver south to avoid possible ambushes along Highway 1. Approaching the heavy-defended village of Thon La Chu, the headquarters of the Hue City Front, Sweet’s squadron ran into well-prepared enemy positions in a tree line. Caught in the open, the soldiers were pinned down by grazing fire and mortar rounds began exploding among them. Throughout the day, the Americans were engaged in a firefight, with helicopters swooping in to bring ammunition and evacuate dead and wounded. With casualties mounting, remaining in place meant the squadron would be cut to shreds. Sweet ordered his men to charge the enemy positions. Taking more casualties, the Americans captured the tree line and set up defensive positions. The low cloud cover prevented American fixed-wing aviation from adding its weight to the battle.

When darkness fell, Sweet’s squadron shrunk from 400 men to 200 effectives. Staying put was out of the question, and Sweet made the decision to break out to the west and later flank the Thon La Chu. During the night of February 3-4, the depleted squadron slipped away in the night, unnoticed by the enemy.

Starting on February 4, Marines in the Triangle began making incremental gains. The fighting at close quarters was brutal, and crossing a street under fire was deadly, as well as entering a building through a door or a window. Before entering, the Marines would blast a hole in a wall with C4 explosives, followed by grenades.

Built in French colonial style, the buildings had thick walls to keep cool, and the light M72 LAW rockets carried by Marines in the field were frequently insufficient to defeat them. The 106mm recoilless rifles, both tripod-mounted and mounted on Ontos, proved invaluable. Their heavy 20-pound rounds tore out big chunks of a wall or brought down the wall altogether. A light and quick Ontos would dart out from behind cover, fire off a volley of its six rifles, and quickly move back. Several rounds from an 81mm mortar could bring a whole roof down on the building’s defenders.

Any tank that entered a street was immediately bombarded with B40 rockets, with some taking close to a 100 hits. Their armor was tough enough to keep the tanks from being destroyed, but there were casualties among the crews. Initially, the Marines were prohibited from using tank cannons and flamethrowers in the city and employed them as mobile cover for infantry and machine gun platforms. But as the fighting wore on, prohibitions were ignored.

The Treasury building with its extra thick walls proved invulnerable even to 106mm rifles until Major Ralph Salvati, 2/5th Executive Officer, brought up E8 CS gas launchers from the MACV compound. The launchers, firing 64 canisters in volleys of four, rained on the Treasury building, followed by Marines from Company F wearing gas masks. The PAVN soldiers, lacking gas masks, were forced to abandon the building.

Shortly after Company B, 1/1st Marines reached the Triangle from Phu Bai, the Vietnamese finally brought down the An Cuu Bridge. The resupply would now have to be carried out by helicopter and riverboats under fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Cheatham continued pressing west along the waterfront, with his left flank anchored on the Perfume River. Fighting was slow and brutal, with progress some days measured by several captured buildings. Mounting casualties were made good by a flow of volunteers and replacements new to the country, frequently arriving in clean, pressed fatigues. The provincial capital, housing the headquarters of the PAVN’s 4th Regiment, was retaken on February 5. Organized PAVN resistance in the Triangle collapsed, although it would take several more days to reduce the last pockets of stubborn holdouts.

Gravel’s 1/1st Marines cleared the area north of the destroyed An Cuu Bridge, and by February 13, Marine engineers built a pontoon bridge over the canal, and truck convoys from Phu Bai rolled once again. As more and more territory came under American control, terrified civilians came streaming in seeking shelter from death that seemed to be everywhere.

In the Thon La Chu area, Sweet’s squadron was joined by another from the 1st Cavalry Division, the 5/7th under Lt. Col. James Vaught, where three PAVN battalions defended the Hue City Front headquarters. Despite assistance from artillery, helicopter gunships, and naval gunfire, the Army troopers could not progress against defenders who outnumbered them. The PAVN supply route to the western mountains continued functioning, and several more battalions entered the Citadel through the southwestern gate.

In the Citadel, by the end of February 7, General Truong had three battalions from the 3rd and one from the 1st Regiments, three airborne battalions, parts of two armored cavalry squadrons, and a severely depleted Hac Bao company. However, heavy fighting reduced some South Vietnamese battalions to 200 men and Truong requested help from General Cushman.

On February 10, enemy resistance, other than a few pockets, collapsed in the Triangle. After a battalion from the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division took over the fight for Hue’s southern and eastern suburbs, Cushman ordered Colonel Hughes to send Marines to the Citadel.

On February 11, ARVN troops cleared the neighborhoods around Tay Loc Airfield, and Marine helicopters delivered a company of South Vietnamese Marines and one from 1/5th Marines to Mang Ca before the weather turned bad. The next day, two more companies from 1/5th Marines under Maj. Robert Thompson and five Marine tanks moved by boat to Mang Ca.

Thompson met with Truong, and they split the Citadel into two areas of operations. The South Vietnamese troops would operate in the western part of the Citadel. The U.S. Marines would relieve the depleted airborne battalions in the eastern half of the Citadel and attack south. However, neither officer knew that the Vietnamese paratroopers, which belonged to the ARVN General Reserve, had already pulled back from their positions under orders to return to Saigon. During the night, the PAVN occupied the abandoned positions. When a Marine company from 1/5th moved forward the next morning, it ran into an ambush and took casualties.

The Marine attack south along the eastern wall of the Citadel immediately ran into strong defensive positions. Bunkers, trenches, and snipers were everywhere. The enemy resistance appeared heavier than in the Triangle and the American attack temporarily stalled in the face of mounting casualties.

On the west side of the Citadel, the South Vietnamese marines had a hard time after relieving the battered 3rd Regiment. The ARVN forces lacked heavy weapons, such as 106mm recoilless rifles used by the Marines with great success, and their casualties were disproportionately heavy.

Due to the South Vietnamese government’s request to spare the historical nature of the Citadel, the American command held back from using artillery and air strikes. However, due to heavy enemy resistance, Hughes was eventually permitted to use all the firepower on hand, except for firing on the Imperial Palace.

From February 13 to 15, reinforced by Thompson’s fourth company and supported by M48 tanks, the Marines battled for positions around the heavily defended Dong Ba Gate and its massive tower in the eastern wall of the Citadel. Even after the tower was destroyed by artillery, naval gunfire, and air strikes, the PAVN doggedly hung in the rubble before giving up their positions.

The push south along the wall continued on February 16 under heavy flanking fire from the Gia Hoi Island in the Perfume River to the east and from the walls of the Imperial Palace to the west. While the Marines could call fire on the Citadel’s outer wall, they could do nothing about enemy fire coming from the Imperial Palace.

The PAVN constantly launched counterattacks, and fighting was house-to-house and room-to-room. The Hue City Front command knew they would be eventually defeated, but each day they could hold the Citadel was a political statement.

Thompson and his command staff identified a pattern in PAVN’s movements during the previous fighting. When the action halted for the night, the PAVN troops moved back from their positions to reoccupy them the next morning. To take advantage of this pattern, Thompson launched an attack under cover of darkness at 3 a.m. on February 21. A platoon from Company A in three groups occupied buildings identified as key to enemy defensive positions.

When the PAVN soldiers approached their positions in the morning, they came under withering Marine fire. The rest of Thompson’s battalion moved up to secure their gains and by the end of the day, the Marines came within 100 meters of the southern wall. The same day, two newly arrived South Vietnamese ranger battalions cleared the last pockets of resistance southeast of Hue.

During February 21-22, enemy resistance in the hamlets surrounding Thon La Chu began to weaken, and during the night, the enemy began to withdraw closer to Hue. By the end of February 22, the enemy only controlled the Imperial Palace and the southwestern corner of the Citadel. After the South Vietnamese marines recaptured the Imperial Palace, the Hue Front Command ordered its troops to break off contact and withdraw to the western mountains.

By February 25, the last scattered PAVN defenders completely abandoned the Citadel and attempted to escape to the north and west under constant American artillery fire. After a few more days of sporadic skirmishing, the American command declared the Battle of Hue over on March 2.

The beautiful city of Hue lay in ruins. More than 70 percent of buildings and the majority of its infrastructure were destroyed or damaged during the fighting. Bodies of civilians caught in the crossfire and PAVN soldiers were strewn everywhere. After the battle, several mass graves containing over 3,000 bodies were discovered in the vicinity of Hue, many bearing signs of torture and execution. Despite evidence to the contrary, Communist leadership only admitted to a small number killed at their hands. Including those found in the mass graves, civilian casualties were estimated at more than 5,000.

The fighting in Hue was the longest battle of the Vietnam War. Consistent underestimation and disbelief of the situation on the ground by Generals Westmoreland and LaHue prevented them from dispatching sufficient forces and firepower to defend Hue. The U.S. Marines suffered 147 dead and 857 wounded; the U.S. Army lost 74 killed and 507 wounded. The South Vietnamese Army losses were 421 killed, 2,123 wounded, and 30 missing. Estimates of PAVN and Viet Cong losses vary greatly, from 2,500 to 5,000 killed.

Despite their generally poor reputation, the South Vietnamese forces under General Truong’s leadership fought well and bore the larger share of the fighting in the Citadel, as indicated by their casualties compared to American losses.

Although the PAVN and Viet Cong attacks throughout South Vietnam were defeated after several days, the battle of Hue was the most successful enemy operation during the Tet Offensive. By the time the struggle was over, more than 8,000 PAVN regulars, an equivalent of two divisions equipped with mortars and recoilless rifles, had fought for the city. However, the failure of the PAVN to overrun the Mang Ca and MACV compounds allowed the Allied forces to use them as springboards from which to launch counter attacks to liberate the city. Likewise, PAVN’s failure to destroy key Nguyen Hoang and An Cuu bridges allowed the Americans to rush reinforcements during the crucial first days of the battle.

Despite the month-long occupation of South Vietnam’s third-largest city, the main goal of the Tet Offensive—to bring about a popular uprising—was a failure. The majority of South Vietnam’s population remained indifferent, concerned with their survival and being left alone to live their lives.

Despite failing to score a political victory at home, the Communists scored a major one abroad, especially in the United States. Images of death and destruction and mounting casualties, brought by television into American living rooms, had a negative impact on the American public opinion toward the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments