By Peter McQuarrie

On October 15, 1942, a total of 22 men, all British subjects and all prisoners of war captured by Japanese military forces in the Gilbert Islands in the Central Pacific, were executed on Betio islet at Tarawa Atoll..

Those executed were mostly civilians, 17 New Zealand coastwatchers, an Australian (Reg Morgan), who also did coast watching work, two Englishmen, a Scotsman, and one European Fiji citizen. The men were beheaded, and their bodies were buried on Betio in separate graves, the location of which was later obscured when the Japanese constructed military fortifications and an airfield in the area.

Operation Galvanic, in November 1943, of which the Battle for Tarawa was a component, caused further obscuration of the graves, and when the United States Marines defeated the Japanese defenders and took control of the islet many more graves were created to bury the war dead of both sides. The more than 6,000 dead were hastily buried in often unmarked graves scattered all across the islet. After U.S. forces occupied Tarawa, Navy Seabees rebuilt the Japanese airbase, leveling and compacting the airfield and its approaches. The work disturbed grave sites.

Over the years since the end of World War II, hundreds of American and Japanese remains have been recovered from Tarawa, but nothing among the remains has been identified as belonging to the 22 British subjects.

Coast watching in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands began in September 1939, with the British declaration of war on Germany. Island observers reported any ship or airplane that they sighted from their coasts to the colony headquarters at Ocean Island (Banaba). The initial fear was of German commerce raiders disguised as merchant ships, but by early 1941 the focus had shifted to looking for aircraft and ships of a Japanese invasion force.

The Gilbert and Ellice Islands were in key locations between the Japanese-held Marshall Islands and British Fiji in the Central Pacific, along with New Zealand and Australia further south. In an effort to improve the effectiveness of the coast watching service, the Australian, British, and New Zealand governments agreed in March 1941 that New Zealand would provide radio equipment and personnel to upgrade the Gilbert and Ellice coast watching network. The 14 new stations would be part of a much larger South Pacific network controlled by the New Zealand Naval Board in Wellington. Australia would provide a similar coast watching network for the Southwest Pacific.

Three days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, coastwatchers on the three northern Gilbert Islands were captured and their radios destroyed. These New Zealand men, soldiers and Post and Telegraph Department radio men, were taken to Japan, where they spent the remainder of the war in Zentsuji Prison on the home island of Shikoku.

At the time the Japanese focus in the Gilbert Islands was on constructing a seaplane reconnaissance base at Makin Atoll. However, they did visit Tarawa, a port and trading center in the central Gilberts, to inform the inhabitants that they were now under Japanese control and that no one was to leave the island. No New Zealand coastwatchers were stationed on Tarawa; instead, coast watching and radio reporting were the duties of European administrative staff as well as Gilbert and Ellice Islanders trained in Morse code and radio operation.

By the end of February 1942, two of the Europeans involved in Tarawa coast watching, Dr. K. R. Steenson, Senior Medical Officer, and F. G. R. (Frank) Holland, Education Officer, had escaped from the island along with other Europeans on two launches and had safely arrived in Suva, Fiji. One radio operator who remained on Tarawa was an Australian, Reginald (Reg) Morgan, who had been in charge of a radio station owned by the trading company Burns Philp South Seas Ltd.

Japanese Naval forces from Truk, a major military base in the Caroline Islands, occupied Ocean and Nauru Islands on August 26, 1942. Tarawa was occupied on September 3.

Between September 25 and 29, the Japanese shut down the remainder of the Gilbert Islands coast watching stations. The New Zealand soldiers and radio operators were all taken prisoner and transported to Tarawa, where they were held captive in the local lunatic asylum compound on Betio. They were put to work on a Japanese construction project, building a small jetty on the lagoon side of Betio.

On the afternoon of October 15, after the coastwatchers had been imprisoned on Betio for two weeks, the U.S. Navy cruiser Portland arrived on the scene. The Portland was on a lone-raid mission to investigate the Gilberts, particularly the atolls of Tarawa, Maiana, and Abemama, for signs of Japanese activity. The ship approached from the southeast, and the first Gilberts land mass sighted was Tarawa Atoll.

At 1 p.m., Portland’s two single-engine Curtiss SOC Seagulls were catapulted aloft, at first spotting only a single Japanese ship from the air. This was the Tsukushi, an Imperial Japanese Navy survey ship of 1,400 tons which was at anchor in the lagoon at Betio. The Tsukushi had been engaged in marine survey work at Jaluit and was now at Tarawa to survey the lagoon there. Soon, a further three ships were spotted within the lagoon, but not at the anchorage. These were the Yunagi, a destroyer, the Hitachi Maru, a merchant ship of 6,172 tons which was designed for carrying both passengers and cargo, and the Ukishima Maru, a naval transport ship of 4,731 tons.

The armament of the Seagull scout planes was limited to one machine gun and a maximum bomb load of 650 pounds. This enabled each plane to strafe the ships with machine-gun fire and to have a single bombing opportunity with one 500-pound bomb each. The Seagulls dive bombed the merchant ship, Hitachi Maru, as it was approaching Betio. According to Japanese reports there was a near miss which caused only slight damage to the ship, but some laborers who were passengers on the ship were killed or injured. The Tsukushi, at anchor, was strafed, with the result that the ship’s launch was sunk, but there was little other damage.

At 2:29 p.m., the Portland commenced firing her main guns at the Japanese ships, aiming with the assistance of information from her observation planes. As the Portland steamed along the south coast of Tarawa, a total of 237 rounds were fired over the next 20 minutes, and the observers claimed that heavy smoke was seen billowing from the Hitachi Maru. Japanese sources confirm that the Hitachi Maru was damaged, but not seriously. At 2:50 p.m., the Portland ceased firing and changed course for Maiana Island. No Japanese activity was observed at Maiana or Abemama, and the cruiser steamed away from the Gilbert Islands.

During the raid one of the prisoners, Reg Morgan, escaped from the compound where captives were being held. The Japanese hunted down Morgan, killed him, and then killed all other European prisoners, apparently in retaliation for the escape and the Portland raid.

It seems likely that to the coastwatchers and other prisoners on Betio the raid was an attempt to rescue them. They would have heard the shells flying over them toward the ships in the lagoon, and apparently they heard, saw, and waved to the small observation planes. Perhaps they cheered and made a lot of noise. This behavior, in addition to Morgan’s breakout, was more than the Japanese could tolerate, and they executed all their prisoners.

But were the executions really an act of reprisal for the Portland raid? On October 16, the day after the Tarawa executions, nine captured U.S. Marines were executed at Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands. The Kwajalein commanding officer reportedly stated that he had received orders to execute the American Marines. Had the Tarawa commanding officer received similar orders?

Probably the full circumstances surrounding the decision to execute the prisoners will never be revealed. However, even if no specific order was given to execute the Tarawa prisoners in October 1942, general guidelines covered the circumstances when it was permissible to kill prisoners. These described such situations as a prison uprising that required the use of firearms to suppress, escaped prisoners turning hostile, or an enemy attack that threatened to free prisoners. These general orders stressed that it was imperative not to let prisoners fall into enemy hands. It seems that the Japanese at Tarawa considered the Portland attack and escape of one prisoner to be sufficient justification to execute all prisoners.

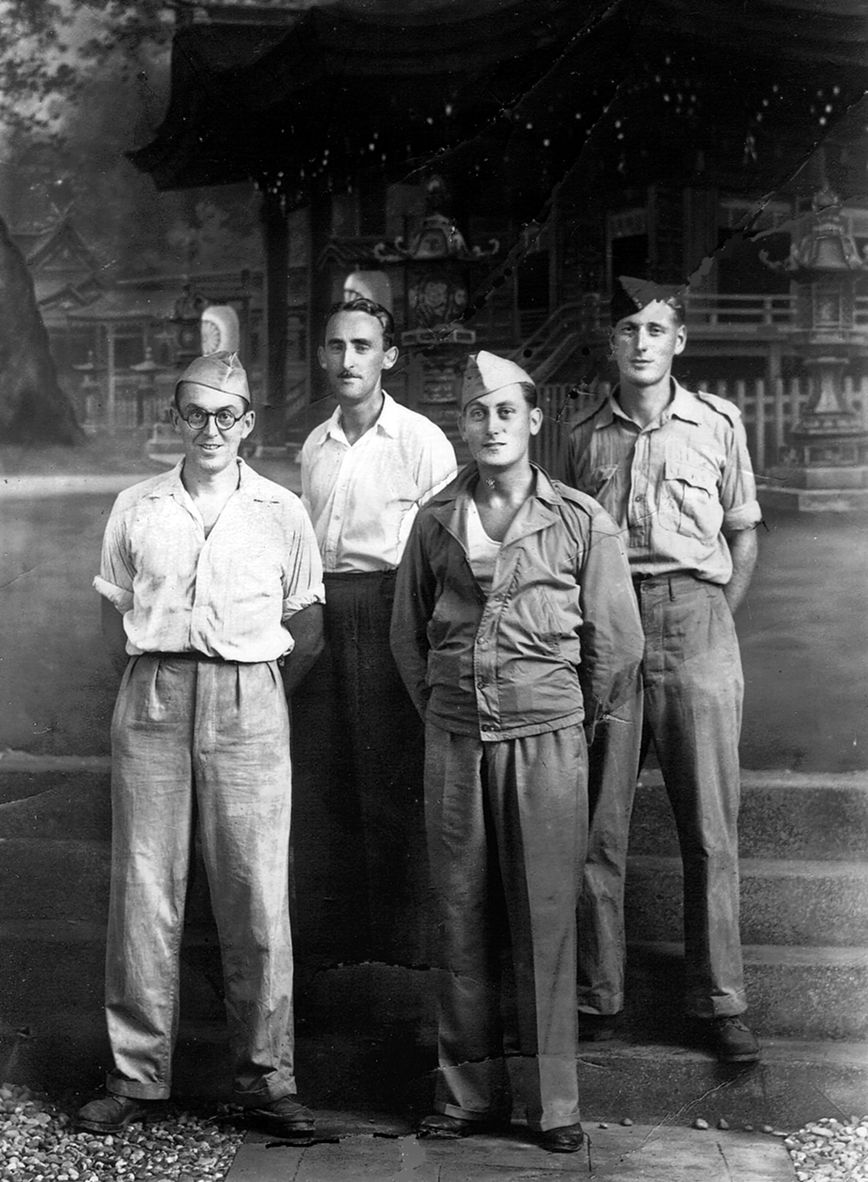

Those executed included the seven New Zealand coast watching radio operators and their 10 soldier companions; Reginald Morgan, the Australian radio man who had been attested into the Fiji military forces as a lieutenant; four civilians—the government pharmacist Basil Cleary, originally from Fiji; retired master mariner Isaac Handley; Reverend Alfred Sadd from the London Missionary Society’s Beru mission station; and A.M. McArthur, a retired trader from Nonouti Island.

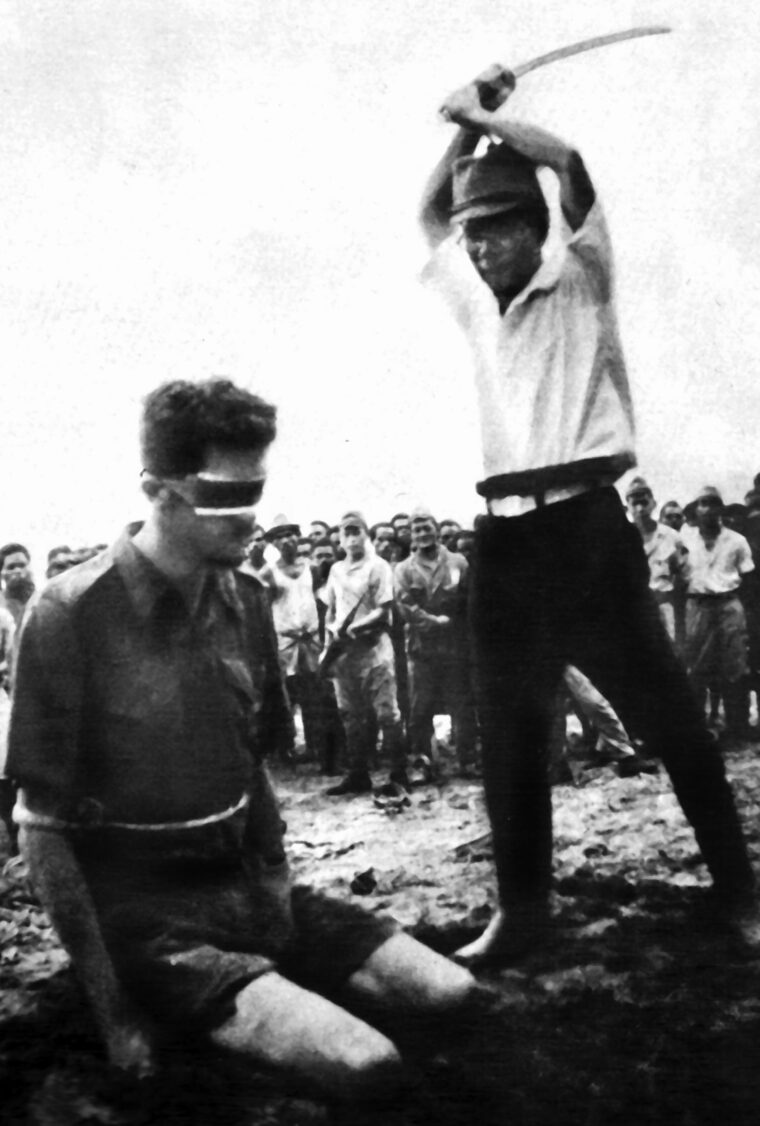

A Gilbert Islander named Mikaere, was an eyewitness to two of the executions. He remembered, “One European ran away, and the Japanese searched for him at the west end of Betio. One Japanese came to the Bishop’s fence and showed them his sword, there was fresh blood on it, he said the European was dead… I saw the Europeans sitting down in line in front of the first house inside the lunatic enclosure. One Japanese stepped forward to the first European in line and cut off his head. Then I saw a second European have his head cut off, and I could not see the third one because I fainted.”

No one saw the remainder of the executions, but two reliable witnesses, Frank Highland, a local resident of partial European ancestry, and Constable Takaua, saw the remains after the bodies had been burned in an old babai pit, or taro garden.

“I went with Constable Takaua and saw the bodies … burnt in a babai pit,” Highland remembered. “Takaua watched, and I went in the pit and lifted up coconut branches and corrugated iron… There were no heads on the bodies. Then I kept watch while Takaua looked.”

At this time the Catholic missionaries became the only Europeans left alive in the Gilbert Islands. There remained many others of mixed European and Gilbertese or Marshallese descent, but the Japanese treated those of mixed race in the same way as they treated the full-blooded Gilbertese and did not harm them.

The Japanese spared the Catholic missionaries because most came from countries that were allies of Japan or neutral—France, Germany or Switzerland. Given that a group of Australian nuns on Abemama were treated no worse than the French sisters who were present, another factor contributing to their special status may have been the close association between their church and Italy, the third Axis power. The Japanese commander on Tarawa told Bishop Terrienne that leaving the Catholics alone made good propaganda.

Nonetheless, although the European members of the Catholic mission were not molested overtly by the Japanese, much of their property was stolen, and they were frequently in fear of their lives. The Japanese regarded them with constant suspicion and refused to give them permission to travel between islands in the Gilbert chain.

After the Gilbert Islands returned to Allied control in November 1943, the deaths of the 22 Europeans were investigated. In January 1944, Captain John R. Grigg, a New Zealander on loan to the Gilbert and EIlice Islands Labour Corps from the Fiji Military Forces, was assigned the task of locating the remains of the 22 Europeans killed by the Japanese.

He reported on his work: “When I received instructions to find the remains so that they might receive a decent burial, I asked Josefa to show me the spot. He also brought along a native medical dresser who knew the exact locality. Each separately walked to the only remaining landmark—a well with a circular stone top. From this point they paced some distance in a northerly direction and pointed to a certain spot. I contacted the officer in charge of the unit in that area, and he told me that when he had first taken up his position there had been a deep hole but he had noted nothing unusual about it. He reminded us that the whole place had been so bombed and shelled that everything had been changed beyond recognition. He had arranged for a bulldozer to fill in the excavation from which the Japs had probably obtained spoil for a fortification nearby, and coconut tree trunks and heavy roots embedded in the coral sand would now make it extremely difficult to reexcavate. Even if the pit were laboriously cleared of all its debris it was problematical whether we should find what we were seeking. I reported accordingly to the Resident Commissioner.”

In October 1944, a court of inquiry convened on Betio and established that, although their remains were never found, the Europeans had been killed by the Japanese there, on or about October 15, 1942. Sister Oliva of the Catholic mission stated that she thought the place of burial was covered by the airfield runway which the Japanese later built. In responding to a New Zealand inquiry, the resident commissioner explained that during the U.S. bombardment preceding the Marine landing a shell struck the spot where it was believed the bodies had been buried and that there was no possibility of identifying the remains now.

The remains would have been either completely incinerated and turned to dust when the area was hit by the shell or at least widely scattered as fragments. More than 80 years have gone by, and the area is now covered with domestic dwellings and large trees, which would hamper searching. The outcome of any new search could well be the same as it was in 1944, that there was no possibility of finding the remains.

The three Japanese deemed responsible for the massacre, Commander Matzu Shosa, Lieutenant Yokata, and Shingo Masubusi were never brought to justice.

In addition to articles for WWII History, Naval History, The Journal of Pacific History, Pacific Affairs, and Pacific Islands Monthly, Peter McQuarrie has written two books: Gilbert Islands in WWII (2012) and Strategic Atolls, Tuvalu and the Second World War (1994).

Just one more reason why Hiroshima and Nagasaki were fully justified.