By Marc D. Bernstein

After launching an invasion of Burma (today Myanmar) not long after Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Japanese Army went on to overrun much of China by May 1942 and closed the Burma Road—the vital, 717-mile-long mountain highway built in 1937-1938 that ran from Kunming in southern China to the Burmese border.

The road was crucial to Allied interests because it allowed the British (and later the Americans) to supply the army of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist Republic of China, so that his forces could battle the Japanese.

Supplies would be landed at Rangoon in southwest Burma, moved north by rail to Lashio, and then across the Chinese border via the Burma Road. When the Japanese captured this territory and closed the road in early 1942, the Allies were forced to bring China-bound supplies in by air over the dangerous “Hump”—the towering Himalaya Mountains.

The nationalist Chinese armies that participated in this first Burma campaign had been forced back across the border and beyond the Salween River deep within China’s Yunnan Province. Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell (whose acerbic personality earned him the nickname “Vinegar Joe”), commanding general of U.S. Army forces in the China-Burma-India Theater and Allied chief of staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, had himself walked out of Burma to India.

His obituary of October 12, 1946 (he died at age 63), said: “The operation in Burma was so disastrous that Chinese forces under his command stopped taking orders. And as Allied supplies to China were being strangled, Stilwell and his forces were forced to retreat into India. ‘We got run out of Burma, and it is humiliating as hell,’ the general admitted.”

Immediately thereafter, Stilwell began training a Chinese army in India to retake northern Burma and reopen the road to China.

Meanwhile, as early as the summer of 1942, Chiang Kai-shek’s planners conceived the idea of training 30 divisions in Yunnan for an eventual reentry into Burma from the east. That concentration of troops and supplies, designated Y-Force, would push down the Chinese segment of the Burma Road toward an eventual linkup with Stilwell’s forces moving through Burma. Once Japanese troops had been sufficiently cleared from the critical areas, the Chinese could once again be adequately supplied by land for their titanic struggle with the Japanese in eastern China.

The Making of Y-Force

Y-Force began organizing in early 1943. In late April of that year, Stilwell verbally ordered the forming of an American Y-Force Operations Staff (Y-FOS) under Colonel (later Brig. Gen.) Frank Dorn to assist the Chinese in Yunnan.

Dorn was a highly competent West Pointer who had served as Stilwell’s aide and in several other key staff positions in the CBI since early 1942 and had walked out of Burma with Stilwell.

On June 18, 1943, formal written orders confirmed the establishment of Dorn’s Y-FOS. Y-Force itself would be entirely under Chinese command, but Dorn’s Americans would have several important functions. They would assist in training and supplying the Chinese, exchange intelligence, provide air-ground liaison, and report on the needs of the frontline troops in the coming offensive.

Initially, Dorn had only a handful of officers to accomplish these duties, but by January 1944, Y-FOS had grown to a staff of 654 officers and 1,629 enlisted men. Importantly, American portable and field hospitals joined Y-FOS to provide a level of care hitherto unknown to Chinese troops. American advisers were attached to units as large as Chinese armies and as small as regiments.

It had originally been hoped that the Chinese would be ready to move in Yunnan by October 1943. All supplies for Y-Force needed to be transported by air over the Hump of the Himalayas from bases in India, but this had been accomplished with sufficient speed.

Still, the Chinese dallied. Finally, in mid-April 1944, after being threatened with a cutoff of Lend-Lease supplies to Y-Force, Chinese Minister of War and Army Chief of Staff General Ho Ying-chin gave formal approval to an attack across the Salween by 12 divisions (known as the Chinese Expeditionary Force) under General Wei Li-huang.

General Ho asked Dorn for his personal assurance that the Americans would ferry 50,000 Chinese troops across the Salween and that air support and artillery coordination would be forthcoming. Moreover, Ho wanted the Americans to share General Wei’s command responsibility regarding the supply of food and ammunition to the advancing troops. Dorn readily agreed to all of these requirements.

“One Hundred Victory Wei” and the Roughest Battleground on Earth

General Wei Li-huang, nicknamed “One Hundred Victory Wei,” had spent six years fighting in another part of China, but Dorn considered him inexperienced for the kind of fighting that would be required west of the Salween. His initial 12 divisions were split between the XX Group Army, which would be responsible for the northern half of the area of operations, and the XI Group Army, which would be responsible for the southern half.

Wei’s forces were significantly understrength, with his divisions averaging only about 6,000 men apiece. Thus, he would begin the offensive with approximately 72,000 effectives. To this total would eventually be added three more divisions of the Eighth Army, assigned to the CEF during May 1944.

Wei’s opposition west of the Salween consisted only of the 11,000 troops of the Japanese 56th Division, which held a front stretching over 100 miles from north to south. Though far short of his authorized strength, Wei would have a numerical advantage over his enemy of better than six to one to start the campaign.

But the CEF faced more than just a tough Japanese division that had had two years to perfect defensive positions in this sector of the front. The Salween battleground was arguably the roughest in the world. The river itself, although generally not more than 150 yards wide, is cold and fast flowing. To the Chinese it is known as the “Angry River.”

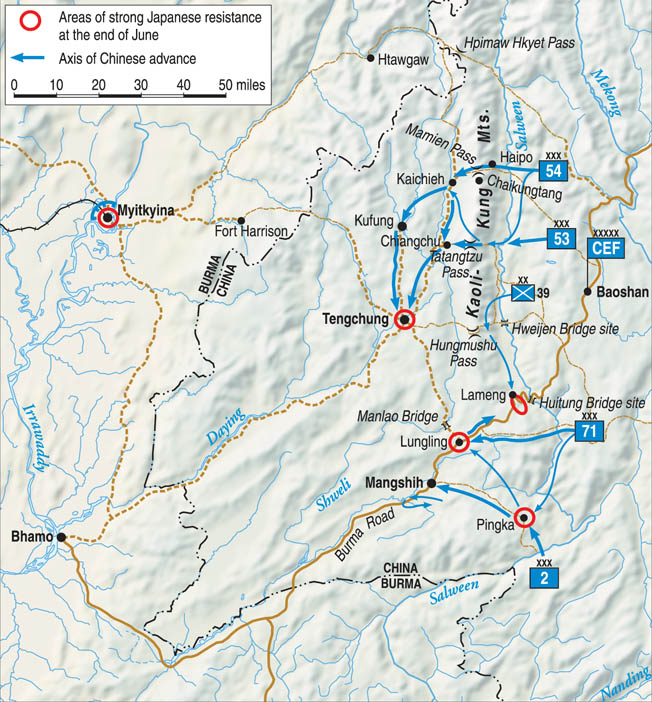

The Salween lies in a gorge 3,000 feet above sea level but just west of it the Kaoli-kung Mountains, a spur of the Himalayas, rise as high as 12,000 feet. The Burma Road, running in a northeasterly direction, bisected the area of operations. North of the road, there were four high mountain passes through the Kaoli-kung. The two most important for the Salween campaign were the Mamien Pass and, to the south, the Tatangtzu Pass, both at about 10,000 feet.

At that altitude, the Chinese would have to weather snow, ice, sleet, and fog in pushing through the passes during the monsoon season, which begins in May. Over a distance of 170 miles from Hpimaw in Burma’s north to Kunlong in the south there were 17 ferries or river crossing points that were usable in 1944. The three bridges across the Salween were destroyed by the Chinese during their retreat in 1942.

North of the Burma Road there were five main trails leading across the Kaoli-kung Mountains from the Salween to the Shweli River, 15 miles west of the Salween. South of the Burma Road there were four main trails leading from the Salween to the road itself, plus several secondary paths. A motor road ran from Kunlong on the Salween to Hsenwi on the Burma Road, 45 miles to the west.

The walled city of Tengchung, north of the road, was a critical road and trail junction, and one of the trails from it led west all the way to Myitkyina in Burma, a distance of 124 miles. A road also led 40 miles south from Tengchung to Lungling on the Burma Road.

A 1944 report on the Salween operations added: “The ruggedness of the country makes it sparsely populated. There are only two towns of any size, Tengchung and Lungling. A number of villages and tiny settlements lie on the rivers and their tributaries and along the trails…. In the Salween Campaign terrain, the distances between villages and points of resistance are small. Hence, distances of a few miles are highly significant. In the mountainous terrain, large bodies of troops cannot be maneuvered, and the operations must be carried on with relatively small numbers. Battalions in these mountains are equivalent to divisions in open country.”

“Succeed—or Else!”

General Wei Li-huang’s operational plan was relatively simple. With the Japanese 56th Division firmly established on the Burma Road and in a position to easily move reinforcements forward along the road, the Chinese decided to attack the Japanese flanks first. After ferrying across the Salween, Wei’s troops would press inland in a double envelopment of the enemy center of resistance from the north and south. When the Japanese were enveloped, Chinese forces would then push directly down the Burma Road.

With the capture of the key objectives of Tengchung and Lungling, it was expected that the Japanese would fall back to Burma. American engineers could get to work constructing a connecting route between the recently built Ledo Road across north Burma and the Burma Road. Once that was accomplished, the land route would be open all the way to Kunming.

Wei assigned the XX Group Army to the sector north of the Burma Road. Initially, it would send three reinforced regimental combat teams across the Salween at three different points. They would each be rapidly reinforced, and these forces would advance through the mountain passes to converge on Tengchung. The XI Group Army was assigned the Burma Road and the Japanese positions to the south of it.

Elements of the 71st and 2nd Armies were to cross the Salween at two points near Pingka and converge on that town. Other elements would bypass Pingka and head northwestward toward Lungling and Mangshih on the Burma Road. The capture of locations along the Burma Road would seriously threaten the defensive positions of the Japanese 56th Division, cutting off units to the east.

With Lungling and Mangshih under attack, the remainder of the XI Group Army would ferry across the Salween. If these early operations proved successful, General Wei would commit his reserve to an attack directly down the Burma Road.

The U.S. Army official historians commented, “The plan was good, but the hour was late and this would be a great handicap.” Indeed, the monsoon rains arrived about a week after the first crossings of the Salween on the evening of May 10-11.

On April 27, Chiang Kai-shek telephoned General Wei at his Paoshan headquarters to order some late adjustments and set the date for launching the offensive. Chiang instructed his commanders to “succeed—or else!” Dorn later notified Stilwell that his hopes were high for reaching Myitkyina before Stilwell’s five Chinese Army in India divisions did.

Operations Begin

The Chinese commanders were concerned about the vulnerability of their troops during the Salween crossing operations, but the Japanese elected to put up virtually no resistance at the crossing sites, preferring to establish their main defensive positions along the Kaoli-kung ridgeline 10 miles west of the river in the XX Group Army sector.

Units of the Chinese 39th Division were ferried across the river a few miles north of the wrecked Hweijen Bridge without incident on the night of May 10-11 and began moving south parallel to the river toward the bridge site and a trail leading from there westward to Tengchung.

North of the 39th Division’s crossing, units from the 36th and 116th Divisions crossed at Mengka Ferry on May 11-12, heading toward Tatangtzu Pass. Farther north, elements of the 198th Division (54th Army) crossed the Salween near Haipo on the night of May 11 on rubber boats and bamboo and oil drum rafts, with the intention of advancing on Mamien Pass. The current was so strong that it took four engineers to paddle just four infantrymen and their equipment across the river at a time.

In the south near Pingka, the 228th Infantry Regiment from the 76th Division crossed 11 miles below the town, while elements of the 88th Division were ferried to a point seven miles northeast of the town. Serious fighting did not begin in any of these sectors until the Chinese were well established beyond the river. The only casualty was one man who drowned.

The 198th Division pressed westward toward Mamien Pass, making contact with the first outpost of the Japanese 2nd Battalion, 148th Regiment there on the afternoon of May 12.

The main body of the division was in position for an attack on the pass by May 15, while other elements bypassed Mamien Pass entirely and moved over trails toward the Shweli River.

On May 17, Chinese guerrillas occupied Hpimaw Pass, far to the north of Mamien Pass, and units of the 198th Division were diverted north to reinforce the guerrillas.

By that same date, the elements that bypassed Mamien Pass had reached the Shweli River and made contact with the Japanese in a surprise attack at Chiatou, where heavy casualties were inflicted on the enemy. Pushing farther south along the Shweli, the Chinese occupied Kiatou on May 24.

Alarmed, the Japanese counterattacked the Chinese in the Shweli River Valley and both Chiatou and Kiatou were retaken by the enemy before the end of May. Fighting raged there until mid-June, with Chiatou changing hands three times and Kiatou twice before the Japanese were finally driven west of the Shweli River and south of Kiatou.

In Mamien Pass, the Chinese were stalled by stubborn enemy resistance, with the Japanese 2/148 falling back to the fortified village of Chaikungtang, where it joined two battalions of the Japanese 113th Regiment that had been rushed north to reinforce after the 56th Division determined that the major Chinese threat was in the northern sector of its front. The Japanese held out at Chaikungtang, blocking movement through the pass, until June 13.

An American report noted that “so fanatic was the Jap resistance that even after the Chinese troops surrounded and entered a pillbox, the Japs charged with bayonets and had to be exterminated one by one inside the positions.”

In addition, evidence of Japanese cannibalism was discovered. First Lieutenant Richard D. Shoemaker, part of the Y-FOS liaison team with the 54th Army, wrote: “[W]e saw the body of a dead Jap. The head, hands and feet still had flesh on them showing no sign of decay…. The rest of the body was bare and no flesh whatsoever on the bones. The skin had the appearance of having the flesh cut off—here were no jagged or uneven edges.” Some of the bodies Shoemaker found were located adjacent to a Japanese kitchen.

Tatangtzu Pass and Hungmushu

At Tatangtzu Pass, south of Mamien, the Chinese 36th Division (54th Army) also encountered serious difficulties. By the evening of May 12, it had surrounded the Japanese at the eastern end of the pass. But the enemy launched a devastating attack that night and drove the Chinese back to the Salween. The 36th Division’s morale was smashed, and it would be out of action for several weeks.

The 53rd Army continued the attack against the pass with the 116th Division moving from the north and the 130th Division from the south. An American observer noted, “Several days were wasted and heavy losses incurred … in suicidal charges by a succession of squads against enemy pillboxes. Teamwork in use of weapons and supporting fires and the use of cover were conspicuously lacking … most casualties resulted from attempts to walk or rather climb up through inter-locking bands of machine-gun fire. As a demonstration of sheer bravery the attacks were magnificent but sickeningly wasteful.”

The fighting for Tatangtzu Pass continued with great ferocity until May 24. On May 18 alone, Tatangtzu village changed hands three times. The Chinese fed additional troops into the battle, and the Japanese, concerned about pressure to the north, eventually decided to thin out the troops blocking the pass. A number of Japanese were successful at breaking through the Chinese lines and escaping to the west.

The Chinese pursued toward Chiangtso, on the trail from Tatangtzu to the Shweli River, and also moved on Watien, on the Shweli River to the northwest. Thus, by early June the Chinese were heavily engaged just west of Tatangtzu and along the Shweli River itself. Watien held out until June 20, and shortly thereafter the Japanese fell back toward Tengchung, 25 miles to the south.

In the Hweijen Bridge area, south of Tatangtzu Pass, the Chinese 39th Division at first made good progress, driving the Japanese 1st Battalion, 113th Regiment from the vicinity of the west end of the destroyed bridge and moving into the village of Hungmushu by May 17.

At Hungmushu there was yet another pass leading through the mountains toward Tengchung, just 20 air miles away. But the Japanese counterattacked successfully and pushed the 39th Division out of Hungmushu and back against the Salween.

By late May, the Chinese were in defensive positions seven miles north of Hungmushu and continued to engage the Japanese there for two weeks. The Japanese decided to withdraw the 1/113 and send it north, thereby allowing the 39th Division to occupy the Hungmushu Pass by mid-June. But the 39th Division was then diverted along a trail paralleling the Salween, under orders to assist the 28th Division of the 71st Army in its attack on the Japanese stronghold of Sungshan on the Burma Road considerably to the south.

On the southern half of the front, the XI Group Army initially had little trouble advancing on Pingka. The Japanese 1st Battalion, 146th Regiment was forced back by elements of the Chinese 76th Division (2nd Army) to the heights overlooking the town. The 88th Division (71st Army), moving from the north, fought through a series of fortified villages in its advance. On May 14, the Japanese struck rear elements of the 88th Division, causing it to stand and fight east of Pingka.

Meanwhile, units of the 76th Division temporarily occupied the town on May 15, but a seesaw struggle ensued with the enemy able to reestablish itself in Pingka and remain there until late September.

The 88th Division joined two other divisions of the 71st Army in a drive on Lungling, and the bulk of the 76th Division was ordered to bypass Pingka, leaving only the 226th Regiment to besiege the Japanese there. That regiment faced the enemy along a semicircular front that extended 24 miles.

The rest of the 76th Division plus the 9th Division headed west toward Mangshih on the Burma Road below Lungling. On June 9, elements of the 9th Division cut the Burma Road four miles south of Mangshih. But one source reported, “The 2nd Army suspended its operations and complained bitterly that it was being discriminated against in supply. Investigating the charge, Y-FOS found that there was an old feud between Headquarters, XI Group Army, and Headquarters, 2nd Army.” The Americans were unsuccessful at resolving the issue, and the Chinese pulled back from the Burma Road.

The Japanese Hold Lungling

In late May, CEF Commanding General Wei Li-huang decided to commit most of the 71st Army in a move on Lungling, except the 28th Division, which was charged with reducing the strong enemy position at Sungshan on the Burma Road, a few miles west of the Salween.

Wei was seeking to exploit the difficulties faced by the Japanese 56th Division, which was in the process of conducting a mobile defense of the entire front, shifting units north and south to meet threats in vital sectors. Both Stilwell and Dorn welcomed Wei’s decision to commit fully all four of his original armies to the offensive while the Chinese Eighth Army was being moved from the Indochina border to augment the CEF.

The Japanese had launched a major offensive in east China that seriously threatened the airfields of the U.S. Fourteenth Air Force, and according to an observer, “Stilwell was most anxious to join his forces with Wei’s for he wished then to move the Chinese Army in India and Wei’s forces to east China to meet the Japanese threat.”

By June 5, the 71st Army had moved 20,000 additional troops across the Salween. In the Sungshan sector, the 28th Division took the village of Lameng, pushing the Japanese back to Sungshan itself, which constituted a mountain fortress. The Japanese, with fewer than a thousand troops at Sungshan, managed to hold out there until early September.

Meanwhile, the 87th and 88th Divisions pushed toward Lungling, reaching the gates of the city by June 7-8. Lungling was crucial to the Japanese effort to hold the line against the Chinese on the Salween front. Its fall would make the Japanese position at Tengchung, 40 miles to the north, untenable and could cause the entire front to crumble. On June 10, the Chinese moved into Lungling, taking three-quarters of the city. But the Japanese quickly regrouped, and by June 16 the 87th Division had been pushed well outside of Lungling.

Major General Sung Hsi-lien, commanding XI Group Army, ordered the 88th Division to fall back alongside the 87th to a line four to five miles northeast, east, and southeast of the city.

The U.S. Army official history observed, “So passed a brilliant opportunity; General Wei’s attempt to exploit his initial successes by committing his reserves had been shattered by [Sung’s] withdrawal before the counterattack of 1,500 Japanese…. Y-FOS personnel considered the Chinese decision to withdraw from Lungling inexcusable because XI Group Army had sent forward no reinforcements to meet the initial Japanese counterattacks. Of 21 battalions that XI Group Army had in the vicinity of Lungling on 14 June, only nine took part in the fighting.”

The Japanese would hold Lungling until early November. In an operation supplemental to the main effort across the Salween, a Chinese force at the far southern end of the front attacked Japanese troops east of Kunlong on May 17 and by late May had effectively neutralized the enemy threat in that area.

General Dorn’s Harsh Criticism of the CEF’s Commanders

General Dorn, as chief of staff of the American Y-FOS, was in a unique position to assess the quality of the Chinese effort during the Salween offensive. His commentary on what he witnessed was both trenchant and telling. From the beginning, he was highly critical of the Chinese commanders, including Wei himself.

On May 16, Dorn had radioed Stilwell: “Says, 33rd Div [commander] … This is not his war, but he is saving his division for second war to come…. Wei Li huang will not issue positive orders to bypass resistance as urged by [CEF chief of staff] Hsaio and me because army and division commanders ‘object’ to having enemy in their rear…. This same old story of lack of discipline, incompetent commanders and weakling on top. We now have total of about 41,000 west of Salween.”

Dorn compiled a summary of his notes and personal comments, which he organized by time period. For May 10-15, he recorded that “justifiable reliefs from command at this time” included CEF commander Wei Li-huang “for weakness in issuance of orders,” Maj. Gen. Huo Kwei-chang of XX Group Army “for failure and refusal to act with decision,” the commanding general of the 33rd Division “for failure and refusal to accept any orders and for stating his refusal to act,” and the commanding general of the 36th Division “for complete incompetence and stupidity.”

During the period of May 15-20, Dorn noted that “younger officers and enlisted men with all Chinese units are universally praised for their attitude and courage.” But he went on to scathingly state, “The 36th Div was the first to make the crossing in its area. On the night of the crossing many fires were lit in the valley of the Salween in total disregard of security or safety. Had the enemy been prepared to defend the crossing, even with light forces, this unit would have suffered extremely heavy casualties….

“The first battery of the 53rd Army artillery battalion to cross the river went into position and immediately fired 242 rounds of ammo without observation of any kind. If any enemy installations were hit, it was by pure accident.

“American liaison officers with the unit attempted to induce the battery commander to stop firing until he had established an observation post, but he refused. This waste of ammunition weighed over 6,000 pounds, the load for 100 porters….

“[E]nemy counter attacks have been successful each night. There is no security and no follow-up of advantages gained. Troops suffer heavy casualties in order to take a position. Their efforts are wasted, and lives lost for nothing, because commanders have no idea that they should guard their gains. There is no continuous effort against the enemy, and no continuous pressure….

“General Hung, Comdr of the 39th Div, informed the American liaison officer with him that when he [the commander] crossed the river, he would wear civilian clothes in order to be safe, and that the American officer could not accompany him as his uniform would attract Jap attention.”

For May 20-25, Dorn wrote, “Plans for the enlarged offensive lumber on. The high command refuses to issue positive orders for the 71st Army to push directly to the Lungling area. Their plan is a series of short jabs at each Jap fortified position along the way—when swift flank moves could avoid all serious fighting until Lungling itself is reached. The result will be about five times the number of necessary casualties; but this plan is ‘safe’ and will be played close to the belt, so it is considered good….”

Dorn reserved his harshest criticism for the CEF commander personally: “Wei Li-huang is a moral coward, and not much of a commander so far. Destroying a few unarmed communist villages is no basis for assuming that he could command an army —much less an operation.

“Recently Wei proposed that we use B-24s as dive bombers at Tatangtzu, because they could dive and drop 1,000-pound bombs. The impossibility of such an idea is obvious to anyone—but Wei…. Weak command all the way through. One American division could have been in Tengchung eight days ago….

“Out of six division commanders, two army commanders, and one group army commander involved up to date, only one division commander has done satisfactorily so far, one division commander is fair, and one army commander is fair. All others have done a poor job.”

In June, Dorn repeatedly expressed frustration with the Chinese effort in the Lungling sector. He observed, “The Chinese should have taken Lungling before this time [June 9]. It is defended by a small Jap garrison. The 71st Army arrived in the area on June 5th; and then spent two days ‘getting into position to attack’—the usual Chinese minuet on the chess board of war—instead of plunging right in.

“In the meantime the Japs were thus given two full days to prepare for the attack which started on June 7th. This is standard procedure with the Chinese—and every time it results in many times the necessary casualties. Chinese commanders play chess—they do not fight…. [CEF chief of staff] Hsiao I-hsu told me—‘It is not the enemy who is holding us up; but our own people who are unable to overcome their fears.’

“When I remonstrated that the troops themselves had demonstrated on a number of occasions their ability to fight, he replied—‘I mean our leaders and commanders.’

“…[XI Group Army CG] Sung insisted [June 20] that he could not hold Lungling, because he had neither artillery ammunition nor air support; though he had an effective combat strength of four to five times the total Jap strength—accepting his reports of Jap troops…. Sung left his headquarters immediately after he had submitted his plan of withdrawal, and remained out of communication for over 24 hours—leaving his chief of staff [without authority to act] at the communication point….

“Sung had had supply difficulties, but nothing to compare to those of the XX [Group Army] in the north, where it was impossible to move animals over the trails, men had to move on all fours over some of the trails, over 150 transport coolies fell off cliffs, over 50 animals were lost in the same way, and where continuous rain, sleet and ice caused the death by exposure of over 300 troops.

“There can be absolutely no excuse for Sung’s conduct—particularly as a supply train of 1500 animals delivered to him about 100 tons on the afternoon of June 16…. Wei ordered Sung to counterattack at once, and to restore his Lungling position. This was on June 17th. He ignored the order and placed his troops in positions of passive defense….

“Hsiao told me that one of Sung’s motives is to preserve the 71st Army intact with a minimum of casualties, and that he was deliberately holding back. No report that Sung makes can be accepted, as he has lied too many times. Hsiao told me plainly to accept nothing that either Sung or [71st Army CG] Chung Pin said.

“Hsiao also states that the CEF has no idea as to what Sung may or may not do, because of his constant refusal to accept or to obey orders. Their great fear is that he may pull out altogether, and without warning. His flagrant refusals amount either to treason or to cowardice; and will delay the completion of the campaign for at least one month—even if he eventually goes into action.”

At Sungshan the Chinese were also stalled, and in early July Dorn railed against the deficiencies of the 71st Army commander. “General Chung Pin, who was placed in command of operations at Sungshan, has continued piecemeal frontal attacks on Jap pill boxes and strongly fortified positions, suffering heavy losses and accomplishing nothing. Chung Pin sent word to the CEF that after numerous attacks on Sungshan, he was out of all ideas as to how its capture could be accomplished; but that he must have more troops….

“Chung sent word that he intended to attack again, using troops of the [Honorable] 1st Div which had been sent to reinforce him. Chief of Staff of CEF told him not to attack until he had received the new plan, and could use newly trained troops. Chung replied that he would attack as a matter of ‘face,’ even though he did not expect much result. After four orders, including a personal order from General Wei, Chung finally agreed to delay the attack (which was to ‘save his face,’ and certainly would fail again).

“The following day Chung sent in one battalion of the Hon 1st Div to attack one of the lesser strongpoints, which was captured with a loss of 60 killed to the Chinese. However, since this area was overlooked by a higher strongpoint, Chung ordered his troops to withdraw after they had taken the place. This is typical of all of Chung’s actions—attack the weak strongpoints, take them with a heavy loss of life, and then because the Japs hold a stronger position, order the withdrawal of the troops….

“After talking with Chung, both [Colonel] Sells and I agreed that Chung was completely whipped. He had no ideas as to how to solve his problem, and would accept none. He insisted that Sungshan must be taken, but could see nothing but a repetition of the wasteful methods he had previously used. He asked me to tell General Wei not to expect much on his front; and to ask General Wei what plan of withdrawal had been ordered in case he (Chung) was unable to take Sungshan.”

On a positive note, as the campaign progressed the Chinese became more receptive to American advice and recommendations, but they refused to accept Dorn’s proposals regarding the relief of key officers. Dorn’s continued exasperation with his allies saw direct expression in a letter he wrote to Chinese Army Chief of Staff General Ho Ying-chin on July 5, 1944.

In it, he castigated both Generals Sung and Chung, stating that “since the middle of June, it has only been with the greatest difficulty that General Sung Hsi-lien has been prevented from withdrawing. He has made greatly exaggerated reports of enemy strength in the Lungling-Mangshih sector, which have been proven wrong for the past three weeks by the fact that the Japanese have never made more than half-hearted local counterattacks in that area….

“He has never committed a force which had sufficient strength to accomplish the assigned mission, but has wasted troops by piecemeal commitments and assignment of limited objectives. The same is true of General Chung Pin…. I know that it is ordinarily not part of my duty to make a report of this kind to you, but I feel that in this case I would be neglecting the trust which both you and General Stilwell have placed in me in the past if I failed to do so.

“I realize the many difficulties involved in removing high commanders, but submit to you that I am convinced without any question of doubt, that as long General Sung Hsi-lien remains in command of the XI Group Army, and General Chung Pin remains in command of the 71st Army, the campaign to open the land route between India and China is in grave danger of failure.”

Despite this extremely negative evaluation, both Sung and Chung remained in command. In a memorandum Dorn wrote for Stilwell in September, however, he revised his initial estimate of the XX Group Army commander, Maj. Gen. Hou Kwei-chang, noting that he “improves with knowledge. Slow but steady and knows how to accept and carry out orders. Nothing brilliant, but will listen to suggestions. He is big surprise of the campaign, as we thought he was no good. He is dependable in a slow though uninspiring way.” By that time, XX Group Army had taken Tengchung after a bitter siege lasting almost two months.

Deficiencies in Artillery and Air Support

Dorn’s general dissatisfaction with the Chinese commanders was matched at times by a critical view of the American air effort backing the CEF. Early in the campaign he wrote, “Air support has been good in the sense that many missions have been flown––more than normally should be necessary under the tactical conditions. But Colonel Kennedy, C.O. 69th [Composite] Wing, is a theorist who has neither any understanding of local conditions and needs, nor apparently is interested in learning anything about them.”

After the monsoon set in, the problem worsened considerably. In early June, Dorn commented that the “situation with regard to air dropping of supplies is growing tense. The Chinese report either good weather or broken clouds during most of each day; 69th Wing reports that weather is closed in, and that either combat missions cannot fly at all or have been forced to turn back; while air dropping missions are unable to get through…. We have repeatedly urged Colonel Kennedy to get supplies to these troops—who if they fail in this mission to take Lungling will wreck the whole campaign.

“The Chinese can see only the weather overhead, and will believe nothing else. Most Americans with Chinese troops are of the opinion that supplies could be dropped; and that if they are not, the entire American effort here will be jeopardized. Personally I believe that full advantage is not taken of temporary breaks in the weather. Kennedy is a theorist, and cannot or will not consider anything which varies in the slightest from his own ideas—which have not been gained in combat experience of which he knows very little.

“His own people are free and outspoken in this idea, and claim that anything which was not done in the Louisiana maneuvers, according to Kennedy, cannot be done at all. The general attitude of the Chinese during the past few days has soured considerably because of our inability to help them.”

Other U.S. air units participating in the campaign included the 51st Fighter Group, 27th Troop Carrier Squadron, and 19th Liaison Squadron, all based in Yunnan. The Tenth Air Force, based in India, also assisted in the effort.

Regarding the use of weapons during actual combat, the Chinese too often chose to dismiss what they had been taught by the Americans. The U.S. official history noted: “Y-FOS observers [with XX Group Army] wrote that Chinese regimental commanders could not ask directly for support from their attached artillery, but had to route their requests through division headquarters.

“When artillery support was granted, it was almost worthless. Targets were not bracketed, and delay between rounds was often as long as five minutes. Artillery observers were sometimes two miles behind the front. The Chinese gunners disdained cover and concealment, drawing on themselves accurate Japanese counterbattery. Chinese pack artillery did not march in orderly fashion but straggled into position. Battery positions were occupied in daylight with individual pack sections arriving at half-hour intervals. The Chinese neglected to maintain their pieces, which quickly grew rusty during the rains.

“To the Americans, the Chinese seemed equally indifferent toward proper care and use of infantry supporting weapons. Chinese mortar crews dismissed their American-taught techniques…. The Chinese infantryman raised the hair on the Americans’ heads by casually using the ring of the hand grenade to hang the weapon from his belt…. At night, an entire Chinese regiment would open up on a Japanese patrol. Ammunition was wasted endlessly, and weapons soon grew unserviceable from constant use and lack of maintenance.”

Cracking the Japanese Strongholds

By early July, after two months of campaigning, the Chinese offensive was bogged down around the Japanese strongholds of Tengchung, Lungling, Sungshan, and Pingka. The Japanese 56th Division, while receiving limited reinforcements, was successfully fighting a brilliant delaying action in the face of vast Chinese numerical superiority.

Japanese air support was virtually nil, but their use of concrete and log bunkers and pillboxes was extraordinary. At Tengchung, for example, in addition to the 35-foot-high wall surrounding the city, the Japanese had constructed literally hundreds of defensive strongpoints. Chinese tactics were often wasteful, unimaginative, and unsuccessful. Compounding their difficulties, on June 24 a Chinese transport plane carrying codes, ciphers, and order of battle information en route from Chungking to Paoshan had mistakenly landed at Tengchung and was captured by the Japanese.

Later in July, the Chinese did launch a well-coordinated attack on Laifengshan, a heavily fortified hill just south of Tengchung. In taking this position, the Chinese followed a plan drawn up by the Americans. After thorough reconnaissance, they attacked en masse instead of in the usual piecemeal fashion.

As an American report also noted, “Having captured the point, the troops continued the advance instead of the usual pause for consolidation and looting.” Flamethrowers were used here for the first time in the Salween campaign. The Japanese suffered an estimated 600 casualties in the attack, and the Chinese by then had moved within a half-mile of Tengchung’s walls. But the fall of the city did not occur swiftly.

As the campaign dragged on, the weight of Chinese numbers, plus the continuous application of American airpower, slowly ground down the Japanese. Sungshan finally fell on September 7, after engineers detonated 6,000 pounds of dynamite in tunnels dug under the mountaintop.

Tengchung was taken on September 14 and Pingka on September 23. Lungling held out longer but was finally occupied by the Chinese on November 3. With the capture of Lungling, the Chinese were able to advance down the Burma Road toward Wanting on the China-Burma border, taking that city on January 20, 1945, and ending the Salween campaign. The connection between the Ledo and Burma Roads was completed, and the first truck convoy in almost three years arrived in Kunming on February 4, 1945.

Over 40,000 Casualties in Eight Months

In more than eight months of heavy fighting, the Chinese absorbed over 40,000 casualties. American medical personnel were instrumental in saving the lives of many Chinese wounded, and many were returned to action. Japanese deaths totaled about 15,000.

To call the Salween campaign a triumph for the Chinese would be stretching the point. What might have been accomplished in two months—if Chinese generals had demonstrated boldness and initiative—took more than eight.

Stilwell’s hopes that the Chinese troops fighting in Yunnan and northern Burma could be moved to eastern China with a rapid victory on the Salween front were thoroughly dashed. Needless casualties were caused by poor tactical handling of troops. Many Chinese commanders were thorough incompetents, more concerned about their business interests than with fighting the Japanese.

Despite the eventual reopening of the road to China, the Salween offensive should stand as a testament to the gross inefficiency of war.

Is there any commentary regarding the American Army Field Hospitals……especially the 22nd Army Field Hospital??

My father was there. I would like to know more about the 22nd as well.

Interesting to read this. My father was there. He was a liaison officer to the 116th Division of the 53rd Chinese Army. Food supplies were a huge issue.