By Walter Zapotoczny Jr.

On August 15, 1937, the Japanese Imperial Army bombed Nanking, the capital of China. These raids were unrelenting until December 13, when Japanese troops entered the conquered city. For the next month Japanese soldiers killed, raped, looted, and burned. More than 300,000 Chinese died. Six months later random atrocities were still occurring. This is the event known to history as the Rape of Nanking.

For the Chinese, this event is an immediate symbol of outrages committed by Japanese troops during the war. During World War II, all of the major participants in the conflict committed atrocities. These actions were often covered up or denied. Arguably, the actions of the Japanese Imperial Army at Nanking are some of the most horrific and controversial.

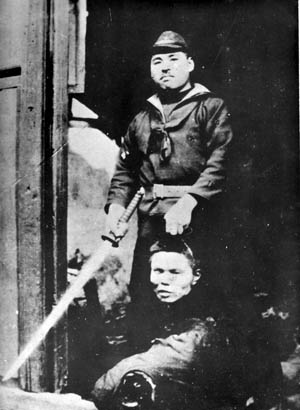

Roy Brooks writes in his book When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy Over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice, “The Japanese turned murder into sport. They rounded up tens of thousands of men and used them for bayonet practice or decapitation contests.” Sometimes the soldiers simply sprayed gasoline on their victims and burned them alive. They skinned some men alive, tortured others to death with needles, or buried them up to the waist in the soil, and then allowed dogs to rip them apart.

The Chinese women suffered even worse, as many were horribly mutilated after being raped. In an attempt to further degrade their victims, the Japanese forced fathers to rape their daughters, or sons their mothers. The Japanese were equally brutal to infants and small children. Other atrocities are simply unspeakable, ghastly beyond description––on the whole as horrifying as those committed by the Nazis.

The following is from the description of the documentary film The Rape of Nanking, based on Iris Chang’s book of the same title:

“Japanese soldiers made a game of torturing and gang-raping women and children. They were encouraged by their officers to invent new and amusing ways of killing and torturing their captives. Murder, rape, and torture, including burning and the rape of children, were believed to be a good way for bolstering the morale of their soldiers.”

This type of behavior is all the more astounding because the Japanese Army had a long tradition of honor, chivalry, and courtesy. The actions of the Japanese Nanking units were not in keeping with that tradition as a whole. After a close analysis of the Japanese soldiers, one can see five factors that perhaps had the greatest influence, either directly or indirectly, on these soldiers:

Indoctrination and training

The economic and political conditions that existed in Japan

The characterization of the Chinese populace as morally deficient

The tactical military circumstances in China

The living conditions of the soldiers

When the conditions that led to the severity of the group’s actions are studied, one might begin to see why the Japanese soldier acted as he did. By understanding the steps that led to their actions, one can perhaps predict behavior from future army groups given similar circumstances.

Indoctrination and Training

During the Asia-Pacific War, the Japanese were widely regarded as the most fearsome light infantrymen in the field, highly disciplined, devoted to their duty, and ready to fight to the bitter end rather than surrender. This reputation was a product of social influence as well as Army training.

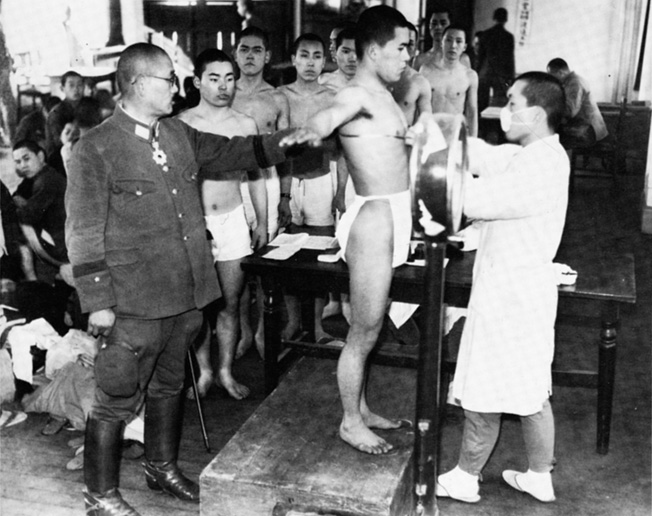

By the 1930s, militarism inundated Japanese society. Many schools gave military instruction to young students. Local elementary schools, for example, taught boys military drills using wooden guns. “The greatest honor,” they would tell the young pupils, “is to come back dead.” There were also Army apprentice schools, which took children directly from school at ages 14-15. Colleges also offered military instruction. According to the 1944 U.S. War Department Handbook on Japanese Military Forces, “In Japan, military indoctrination began from infancy.”

Schools were molding a new Japanese citizen to be indifferent to emotions, to be brutal and obedient. Young boys learned to use wooden guns, while older boys were taught the use of real weapons.

The military wanted well-trained Japanese citizens, and capitalized on the discipline learned at school by continuing the abuse. While some draftees died during the brutality of training, the majority became hardened soldiers.

Once a soldier was in the Army, his training emphasized obedience and loyalty over skilled weapon handling. Officers often lined up new soldiers to slap them in the face, punch them, or beat them with belts, sometimes until blood poured down their faces. “I do not beat you because I hate you. I beat you because I care for you” was a mantra used by officers. Therefore, many of their charges soon became immune to violence and to the killing of civilians.

During a soldier’s training, any lack of discipline was punished by superiors with more beatings. By the time the trainee joined his regiment, it was clear to a soldier that it was in his best interest to obey orders blindly. Japanese infantry training was a gradual toughening-up process. It grew in intensity until long marches with full equipment and stiff endurance tests produced the ability to withstand fatigue, hunger and hardship for long periods.

The obedient soldier was exemplified by the well-known and numerous kamikaze attacks (particularly toward the end of World War II), in which Japanese pilots were trained to fly their planes directly into American ships. In order to save or bring honor to the emperor, the Japanese military were ready to sacrifice their lives.

There are certain international laws and codes of conduct that all soldiers must abide by in time of war yet, obviously, the Japanese did not. For example, the rape of women is certainly not permissible but, according to Iris Chang in her book The Rape of Nanking, “Rape remained so deeply embedded in Japanese military culture and superstition that no one took the rules seriously.” She asserts that a widespread belief among the Japanese military was that raping virgins would make the Japanese stronger for battle. The official military policy forbade rape, thus encouraging the Japanese to kill their victims afterward.

The individual Japanese soldier’s whole outlook and attitude toward life was influenced by his home life, his schooling, his particular social environment with its innumerable repressing conventions, and his military training. In the Japanese social system, individualism had no place. Children were taught that as members of the family, they must obey their parents implicitly and, forgetting their own selfish desires, help everyone of the family at all times. This system of obedience and loyalty extended to the community and Japanese life as a whole. It permeated upward from the family unit through neighborhood associations, schools, factories, and other larger organizations, until finally the entire Japanese nation was instilled with the spirit of self-sacrifice, obedience, and loyalty to the emperor himself, considered a living god on earth.

Superimposed on this community structure was the indoctrination of ancestor worship and of the divine origin of the emperor and the Japanese race. Since the restoration of the Imperial rule in 1868, the Japanese government put much stress on the divine origin of the race. They amplified this teaching by describing Japan’s warlike ventures as divine missions. Famous examples of heroism and military feats in Japan’s history were extolled on stage and screen, in literature, and on the radio. Hero worship was encouraged. Regimentation of the Japanese national life by government authorities, with their numerous and all-embracing regulations, had been a feature for many centuries.

Throughout his military training, the Japanese soldier received instruction that instilled him with a spirit. This spirit could endure and be spurred on to further endeavors when the hardships of warfare were encountered. However, even though his officers appeared to have a zeal, which could be called fanaticism, the private soldier was characterized more by blind and unquestioning subservience to authority.

The determination of the Japanese soldier to fight to the end or commit suicide rather than be taken prisoner may have been prompted partly by fear of the treatment he might receive at the hands of his captors. More likely, though, it was motivated by the disgrace that he realized would be brought upon his family should he fall into the enemy’s hands. (Consequently, he felt that any enemy soldiers who surrendered had acted dishonorably and did not deserve to be treated with dignity or respect. POWs of the Japanese were treated much more brutally than POWs in German custody.)

To understand the origins of the behavior of the Japanese, we must look not only to the time immediately preceding the Japanese invasion of China, but also to the 19th century and indeed before.

Japanese society and values were more than a thousand years old; social hierarchy was very important. The warlords of the islands would employ private armies to go into frequent battle with each other. By the medieval times, these armies had become the Japanese samurai warrior class, where the way of the warrior, Bushido, was the code of conduct. Bushido dictated that the greatest honor a warrior could ever achieve was to die in the line of duty in the process of serving his lords.

So strict was this code of conduct that anyone who failed to meet the high standards of the military service felt it their moral duty to perform hara-kiri or seppuku––in which the warrior commits suicide without flinching by disemboweling himself in front of witnesses.

From the 12th century on, Japan’s powerful military commanders, the shoguns, offered the emperor protection with this strict military service and, over time, they became the real source of power. The code of the samurai, loosely analogous to the concept of chivalry, became the philosophy of protecting the emperor. Although the samurai comprised only two percent of the population, the code was embedded deeply into the Japanese culture and psyche. It gradually became the model of honorable behavior among all men.

The Economic and Political Conditions That Existed in Japan

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 had seen an almost unbelievably rapid modernization of education, infrastructure, engineering, science, and militarization in Japan. This modernization resulted in the downfall of the shogunate and the disempowerment of the samurai.

Partly as a concession to the samurai, the Japanese government instituted an aggressive foreign policy in Korea and Manchuria in mainland China. In 1904-1905, Japan’s power, authority, and self-confidence reached new heights with its defeat of Russia over territorial ambitions in Manchuria.

The prosperity of the 19th century was succeeded by economic collapse in the 1920s and drew down the curtain on Japan’s golden era of prosperity. When the end of World War I halted the previously insatiable demand for military products, Japanese munitions factories were shut down and thousands of laborers were thrown out of work, and the international depression of 1929 further reduced demand. Japan’s population and unemployment were increasing while food supplies were diminishing.

Furthermore, China, enraged by the Treaty of Versailles provision that granted Japan rights and concessions in the Shantung Peninsula, organized widespread boycotts of Japanese goods. These developments hurt the Japanese economy still further and gave rise to the popular belief that Japan had become the victim of an international conspiracy.

During the Great Depression, some influential political groups argued that Japan must conquer new territory in order to avoid mass starvation. People spoke enviously of the spacious territories of other countries, especially of China’s vast land resources. The military propagandist Sadao Araki asked why Japan should accept 142,270 square miles to feed 60 million people, while countries like Australia and Canada had more than 3 million square miles to feed 6.5 million people each. This argument was similar to Nazi Germany’s quest for Lebensraum, or living space, as a pretext for aggressive expansion.

As well as providing new territory for agricultural exploitation, the militarists felt Japan’s prestige and influence would be enhanced by such territorial acquisitions. China, weak militarily, seemed like the perfect target. The Japanese knew that the Chinese Army was in the process of reorganization and buildup and were therefore aware of the importance of acting quickly. Education in particular had reached the point where schooling and war preparation had become almost interchangeable.

“The crumbling of autocracy in Europe after World War I, followed by the tide of democracy, socialism, and Communism, had a dramatic impact on the young people of Japan,” wrote John Toland in The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945. They cried for change as political parties emerged and a universal manhood suffrage bill was enacted in 1924. Japan’s four main islands—Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku (comprising an area scarcely the size of the state of California)—already had more than 80 million people.

“Farmers, who were close to starvation following the plunge of produce prices, began to organize in protest for the first time in Japanese history,” said Toland. “The national economy could not absorb a population increase of almost one million a year. Hundreds of thousands of city workers lost their jobs. Out of all this came a wave of left-wing parties and unions.” These movements were counteracted by nationalist organizations that combined a program of socialism with imperialism.

One of the most popular leaders of the nationalist organizations was Ikki Kita. His words appealed to all who yearned for reform: “Seven hundred million brethren in India and China cannot gain their independence without our protection and leadership. The history of East and West is a record of the unification of feudal states after an era of civil wars. The only possible international peace, which will come after the present age of international wars, must be a feudal peace. This will be achieved through the emergence of the strongest country, which will dominate all other nations of the world.”

In his monumental book New History of the World, J.M. Roberts writes, “When Japan’s wartime economic boom finally ended, hard times and social problems followed even before the onset of the world economic depression. By 1931, half of Japan’s factories were idle and the official unemployment rate was 24.9 percent. Newspapers of those days reported up to 200,000 undernourished children in farmhouses across the country. The position of the Japanese peasant deteriorated as millions were ruined and many had to sell their daughters into prostitution in order to survive. Unable to pay tenant rents amid such rough economic situations, tenant farmers in arrears increased, and landowners acting against these tenants tried to take away their land.”

The political consequences were soon marked by the intensification of national extremism. The collapse of European colonial markets and the entrenchment of what remained of them behind new tariff barriers had a shattering effect. Japanese exports of manufactured goods were down by two-thirds, making it critical for Japan to export to the Asian mainland. Anything that seemed to threaten Japan’s markets provoked intense irritation.

By 1928, many felt that Manchuria was one answer to poverty in Japan. The wilderness could be transformed into a civilized, prosperous area. It could alleviate unemployment and provide an outlet for the overpopulated homeland. Japanese troops had been stationed in the Peking area since the end of the Boxer Rebellion in 1901, and Japan poured a billion dollars into the region, inspiring Japanese, Chinese, and Korean traders and settlers to flood into the area. Many in Japan began to envision Manchuria free of Chinese influence. In the summer of 1931, they took Manchuria away from the Chinese by force and set up a puppet government.

Tensions between China and the Empire of Japan were inflamed by the invasion of Manchuria and creation of the nominally independent state of Manchukuo with Puyi, the last monarch of the Qing Dynasty, as its sovereign. Although the Kuomintang government of China refused to recognize Manchukuo, in 1931 a truce was negotiated.

However, by the end of 1932, the Japanese Army invaded Rehe Province and annexed it to Manchukuo in 1933. Per the He-Umezu Agreement on June 9, 1935, China recognized the Japanese occupation of eastern Hebei and Chahar Provinces. Later that year, the East Hebei Autonomous Council was established by Japan. As a result, at the start of 1937 all of the areas north, east, and west of Peking were controlled by the Japanese.

The Marco Polo Bridge, located outside the walled town of Wanping to the southwest of Peking, was the choke point on the Pinghan Railway and guarded the only passage linking Peking to Kuomintang-controlled areas in the south. Prior to July 1937, the Japanese military had wanted the Chinese forces stationed in this area to withdrawal. They also attempted to purchase land to build an airfield. The Chinese refused, as Japanese control of the bridge and Wanping would completely isolate Peking.

On the night of July 7, 1937, at the ancient stone bridge, an incident ensued that became known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. A Japanese Army company stationed near the landmark was holding night maneuvers about a mile from a large Chinese unit. Just as the signal for the end of the operation came, bullets flew from the Chinese lines. There was a single Japanese casualty—one man missing.

A second company went to the bridge along with a staff officer, who began arranging a truce when another round of bullets poured into the two Japanese companies. The Japanese counterattacked, and it was not until the next morning that both sides agreed to withdraw. Just as the Japanese were pulling out, they again were fired upon and the fighting resumed. The Japanese launched a punitive expedition against Chinese troops that led to war with China.

The Characterization of the Chinese Populace as Morally Deficient

Ideologically, the Japanese were taught that their imperial hierarchy lay at the center of the world morality and that they were superior to all other peoples. As part of this philosophy, China was made the focus of contempt. Initially, some Japanese intellectuals used China to develop a more confident Japanese identity. Japanese teachers instilled hatred and contempt for the Chinese people, preparing young boys psychologically for a future invasion of the Chinese mainland. Iris Chang tells the story about an incident in a school in the 1930s in which a boy started crying while dissecting a frog. The teacher slammed his knuckles against the boy’s head and yelled, “Why are you crying about one lousy frog? When you grow up you’ll have to kill one hundred, two hundred chinks!”

Even at primary schools, it was part of the curriculum for the teachers to teach a very strong hatred toward the Chinese. Military propaganda filled school textbooks in order to prepare the Japanese boys for what was to come. The lives of Japanese males seemed to be an ongoing preparation for a war against the Chinese. Many of the teachers were military officers whose militaristic views were forcefully taught. Telling evidence was given by Hakudo Nagatomi, who was brought up in Korea, which was at the time under Japanese colonial rule.

“I was taught of Japanese racial superiority,” explains Nagatomi, “and the need for Japan to control Asia according to the teachings of the emperor. I was taught to despise other Asians.” These teachings had the desired effect when Nagatomi participated willingly in the barbarism at Nanking. “On my first day in China, back in 1937, I proved my courage by beheading twenty Chinese civilians. It is very hard to say this, but the truth of the matter is that I felt proud of Japan.”

Anti-Chinese attitudes spread in Japan as the popular voices of journalists and politicians condemned China as backward and encouraged Japanese expansion into Chinese territory. By the 1930s, Japanese textbooks taught students to believe in Japan’s superior position in Asia, to view China as a civilization in decline, and to consider Chinese people morally deficient. This view permeated the Japanese military, leading to racial slurs and contempt. Soldiers were told that expansion into China was Japan’s destiny and that heroic behavior brought victory and death. The overall atmosphere of the Japanese military life created soldiers who followed orders, ignored personal feelings, and treated anyone beneath them with the same contempt that they experienced themselves.

By 1937, Japan was engaged in a full-scale war with China that they continued to call “The China Incident.” “Crush the Chinese in three months and they will sue for peace,” War Minister Sugiyama predicted. Patriotic fervor swept through Japan as city after city fell, but almost the entire Western world condemned Japan’s aggression. On October 5, 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a forceful speech condemning all aggressors and equating the Japanese, by inference, with the Nazis and Fascists. He said: “When an epidemic of physical disease starts to spread, the community approves and joins in a quarantine of the patients in order to protect the health of the community. We are adopting such measures as will minimize our risk of involvement, but we cannot have complete protection in a world of disorder in which confidence and security have broken down.”

Japanese reaction was quick and bitter. “Japan is expanding,” said Yosuke Matsuoka, a Japanese diplomat. “And what country in its expansion era has failed to be trying to its neighbors.”

From the beginning of the armed conflict in July 1937, the Japanese government and its supporters, including the mass media, stressed that Chinese Nationalists had planned and initiated armed struggle. According to the official view, Japan had been seeking peace in Asia, only to be dragged into an unwanted military conflict with China.

Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro’s decision to dispatch additional forces to China received enthusiastic support from the major national newspapers. In an article in Asahi (a widely circulated newspaper in Japan) titled “Obviously Planned Anti-Japanese Armed Conflict; Firmly Decided to Dispatch to Northern China; Determined Statement by the Government to China and Other Countries,” the editor used boldface type to emphasize that this incident was no doubt an anti-Japanese armed conflict.

He went on to say that the incident was carefully planned by China and that the Japanese government sincerely hoped that the Chinese side would immediately reflect on its attitude, and that peaceful negotiations would be instituted in order not to worsen the circumstance. The media stressed that the Chinese soldiers and guerrillas were recklessly killing innocent Japanese civilians as well as combatants. Japanese casualties inflicted by unlawful Chinese shootings at the Marco Polo Bridge and other places were widely reported in the newspapers.

When approximately 3,000 Chinese troops in Tongzhou attacked Japanese forces as well as civilians and killed 200 Japanese and Korean residents, the Japanese war correspondents described the event in detail and expressed outrage. Asahi, for example, detailed Chinese looting and destruction in the Japanese community as well as the stabbing and killing of women, children, and infants. In another article on the same page, the Asahi correspondent Tanaka, who had met survivors of the incident, described his feelings of unprecedented fury and declared, “July 29 must not be forgotten.”

A Japanese soldier, Azuma, was stunned at the reluctance of the Chinese Army to fight back. A man who came from such a strict military culture found it incomprehensible that the Chinese would rather be captured than fight an enemy to his death. His automatic impulse was to dehumanize prisoners by comparing them to insects and animals.

Tactical Military Circumstances in China

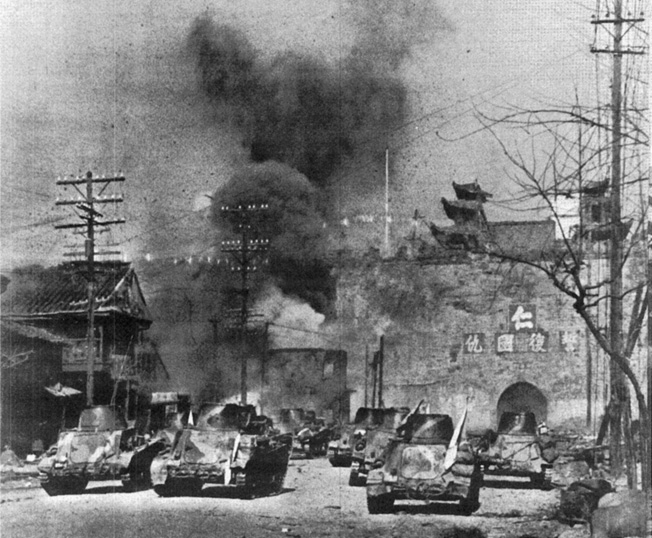

Japan’s expectations of a quick victory over China were shattered when the battle for Shanghai stretched on for several months before the city finally fell in November 1937. The battle was significant in that it effectively destroyed Japan’s goal of conquering China in three months and signified the beginning of an all-out war, not just some incidents, between the two countries.

Divided into three stages, the battle lasted three months and involved nearly one million troops. The first stage lasted from August 13 to September 11, during which the Chinese Army defended the city against the Japanese, who were landing at the shores of Shanghai. September 12 to November 4 represented the second stage, during which the two armies fought in a bloody house-to-house battle in an attempt to gain control of the city. The last stage, lasting from November 5 to the end of the month, involved the retreat of the Chinese Army by the flanking Japanese. Approximately 200,000 died on both sides during the battle.

When Shanghai finally fell in November, Japanese military planners and leaders turned their eyes toward the Chinese capital, Nanking, with the goal of retribution. Commanders pushed their units toward Nanking, quickly outpacing supply lines and telling their men to survive on what they could scavenge. Soldiers robbed villages and the Chinese populace they came across as they passed through. Japanese troops forced peasants to carry equipment and goods. In order to end any threat of resistance, villages were razed. Brutalities were excused in the name of war and of capturing Nanking.

Conquering the capital grew in importance with each new atrocity. The Japanese knew that their job was to kill the enemy, and the barely acceptable conditions of the frontline warfare grew worse, thereby amplifying the animal natures of these soldiers as they marched toward the capital city of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government. Officers promised women and plunder to encourage their men. When the soldiers reached Nanking, their expectations of revenge, sex, and goods, combined with the heightened desire to make an example of Nanking and prove Japan’s dominance, created an atmosphere conducive to brutality.

The imperial troops advanced toward Nanking with heightened aggression, raiding small villages and razing entire cities to the ground. Japanese soldiers keyed up by the heavy fighting in Shanghai and the losses of their own men were ripe for an outlet of the pressure that had built up within them. The Japanese Army’s march to Nanking created multiple factors that made the subsequent atrocities in Nanking highly likely. These were a combination of several factors, both old and new.

First, the near robbery-like requisitioning by Japanese soldiers caused the breakdown of their discipline. Quite a few cases of murder and rape recorded in private diaries were its natural consequence. In this respect, the Japanese troops degenerated into a pre-modern army living off the land to support themselves.

Second, strong anti-Japanese feeling among the Chinese population in the region and the frequent encounters by Japanese troops with straggling and plainclothes soldiers led to the killing of prisoners of war as well as ordinary civilians. Japanese soldiers conducted such ruthless killing because they were highly sensitive to and scared of the plainclothes soldiers. In this respect, the Japanese were fighting a new type of war against the “inner front” as German soldiers had done in Belgium in World War I (and would do again in Russia in World War II).

Third, both sides resorted to burning for their own strategic or tactical purposes. The Chinese implemented a “scorched-earth” policy and burned huge areas to deny the advancing Japanese troops supplies—a campaign of destruction in line with their own tradition. Japanese soldiers frequently burned houses and villages to deprive Chinese irregulars or plainclothes soldiers of their staging bases. Other cases were attributable to the breakdown of discipline, such as Japanese soldiers’ carelessness or the sadistic pleasure they found in seeing houses in flames.

John Rabe writes in his diary, Good Men on Nanking: “The Japanese marched through the city in groups of ten to twenty soldiers and looted the shops. If I had not seen it with my own eyes I would not have believed it. They smashed open windows and doors and took whatever they liked, allegedly, because they were short of rations. I watched with my own eyes as they looted the cafe of our German baker Herr Kiessling. Hempel’s hotel was broken into as well, as was almost every shop on Chung Shang and Taiping Road. Some Japanese soldiers dragged their booty away in crates, others requisitioned rickshaws to transport their stolen goods to safety.”

Confronted by spreading rumors and increasing body counts, some Westerners in Nanking assumed that the Chinese exaggerated family losses to get more relief supplies. By spring, burial stories presented death numbers far beyond initial estimates. Westerners reacted with mistrust. This disbelief was rooted in the feeling that a modern people such as the Japanese could not act in such uncivilized ways. Westerners in Nanking actually expected the Japanese to bring a normalcy back to war-torn China.

Living Conditions of the Japanese Soldiers

Once in the field, the Japanese soldier was supposed to have three meals a day, mainly of rice supplemented with fish, meat, vegetables, and fruit. He slept on a mat on the ground. Often, however, the Japanese Army faced supply shortages, and the soldiers more often than not had to fend for themselves. The sick or dying were often left alone, as medical care was very basic, if not nonexistent. Malaria, dysentery, cholera, and beriberi took many lives.

The Japanese attacked Shanghai and began bombing Nanking in August 1937 with the expectation that the Chinese forces could be easily subdued and all of China would fall in a matter of months. Instead, the siege of Shanghai required four months of bloody fighting. This angered the Japanese high command and the frontline soldiers who had watched their comrades die at the hands of the despised Chinese.

Japanese forces in China faced the constant threat of guerrilla attacks while trying to deal with a severe lack of supplies. These attacks often came from the Chinese armies, but Chinese organizations of various kinds also resisted the Japanese presence.

The battle for Shanghai ended in mid-November with a successful landing of Japan’s 10th Army at Hangzhou Bay in the south, and of the 16th Division at Baimaokou in the north. These landings threatened the Chinese forces’ flank and forced them to withdraw to the west.

On November 19, the 10th Army, led by Lt. Gen. Yanagawa Heisuke, cabled to headquarters: “The group is commanded to put on a spurt in pursuit of the retreating Chinese to Nanking.” The sweating, dust-covered soldiers marched, accompanied by countless swarms of circling flies. The story of the Japanese Army in China at the end of 1937 is one of hard fighting in the capture of Shanghai and outrunning their supply lines on the way to Nanking, forcing them to forage for food. After experiencing heavier losses than expected, they felt a great deal of anger toward the Chinese.

Contrary to the Japanese military’s intention to seek a decisive battle in northern China, Chiang Kai-shek tried to avoid such a showdown in that theater in order to concentrate his military effort in Shanghai. Subsequently, the Chinese troop concentration and the Japanese initial strategy of maintaining a defensive posture in the Shanghai area resulted in stalemated positional warfare.

Historians and observers generally dwell on the more advanced equipment used by the Japanese as compared with the relatively outdated weaponry with which the Chinese equipped themselves at the Battle of Shanghai. The Japanese troops, however, had their own problems. Although they had more artillery, they did not have sufficient or reliable ammunition. Foot soldiers often complained that many of their hand grenades did not explode. One company commander referred to such a defective weapon as “the leftover of the Russo-Japanese War.”

As a result, a ranking officer of the General Staff who inspected the Shanghai front concluded in his report that the Japanese Army’s equipment for close-range fighting was inferior to that of the Chinese troops in terms of both quality and quantity. One soldier of the 19th Mountain Artillery Regiment also said, “The enemy’s machine guns, firing almost without interruption, make our infantry charge nearly impossible.”

In the static battle of attrition, the Japanese losses amounted to 9,115 killed and 31,257 wounded by the end of the Shanghai campaign in early November 1937. The heavy casualties caused bitter resentment at home. After the Chinese defense in and around Shanghai crumbled, the ranking Japanese generals wished to punish the enemy by pursuing him all the way to Nanking.

The 10th Japanese Army started its full-scale advance to Nanking on December 3. This hastily planned and executed military campaign caused considerable confusion and even contradiction in the conduct of frontline troops. Because the Japanese had decided on the Nanking campaign without adequate prior planning or logistical arrangement, they could not supply the advancing troops sufficiently. Apparently, the Japanese depended mainly on water transportation for sending materials forward.

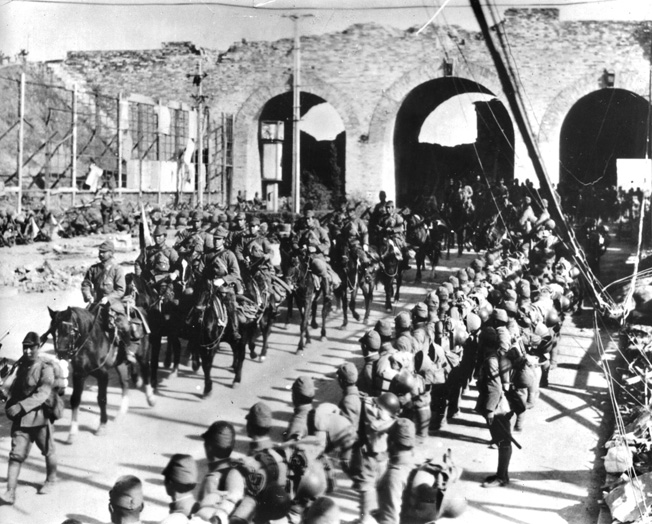

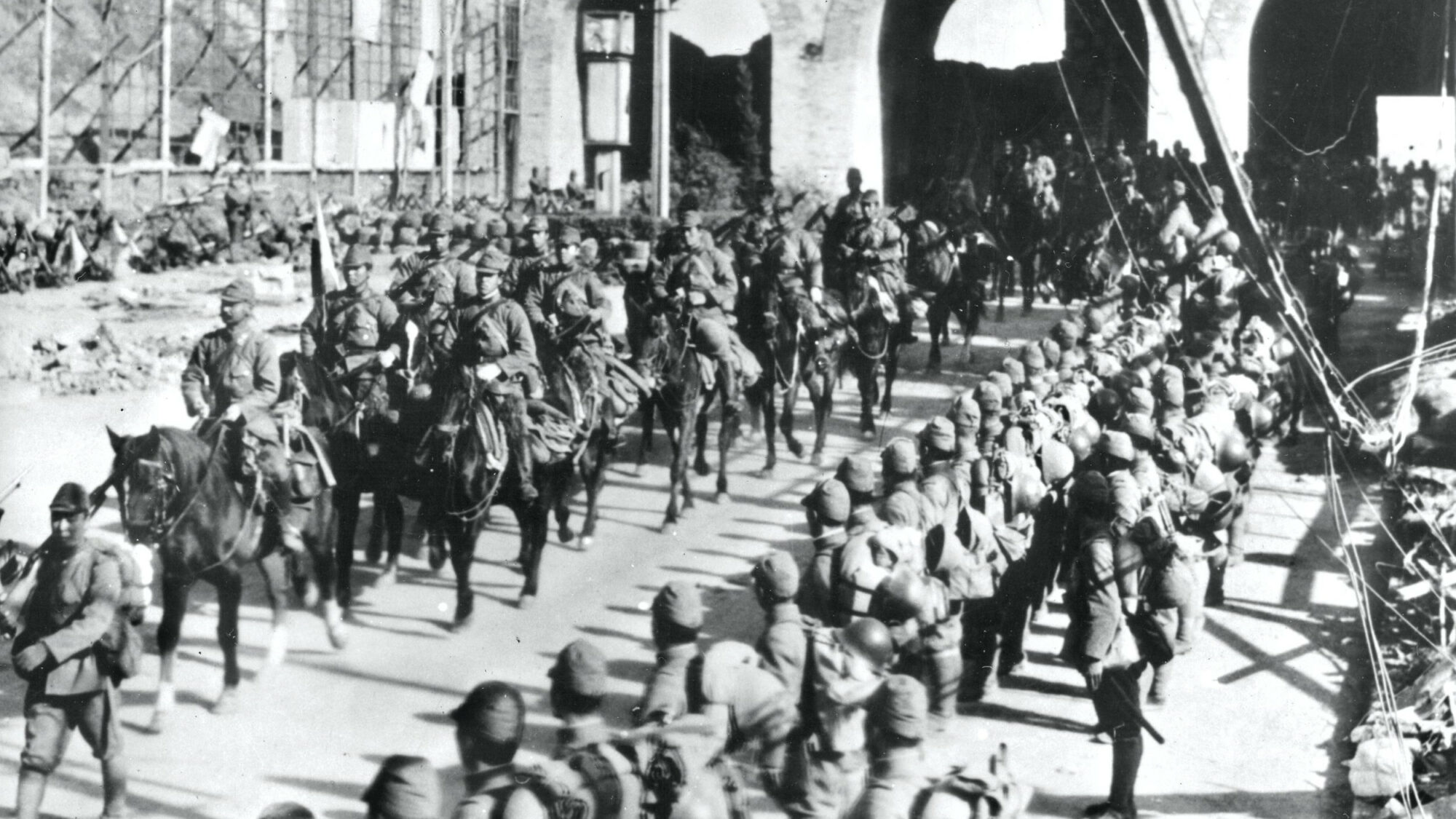

parade triumphantly through the Chungshan gate that leads into Nanking, the capital of China.

Major Kisaki Hisashi, a staff officer of the 16th Division, said in his diary, “Supply columns have not arrived yet. Beyond Tanyang, there is no river route. Moreover, motor vehicles could not run due to the conditions of the road.”

When some troops could not obtain necessary food and other materials, these items were sometimes supplied by air drops. In most cases, however, the Japanese Army had to live off the land. Even General Matsui apparently hoped to procure a substantial amount of food in the enemy’s territory. Although he worried about the supply situation in his diary on November 20, he quickly added, “We need not be concerned about the victuals despite the lack of supply because rice is plentiful in the areas where the troops are operating.”

The Army leadership set forth the same principle in its official guideline for the Nanking campaign; that is, it would give a logistical priority to ammunition rather than food for, after all, a hungry soldier with ammunition can still fight, but a well-fed soldier without ammunition cannot.

A U.S. military attaché’s report underlined this supply policy. According to Major Harry I.T. Creswell, acting U.S. military attaché to China, the Japanese Army used horse-drawn carts as a major means of transportation and loaded most of the carts with ammunition and only a few with rations for the men and forage for the animals. In addition to a severe weakness in their logistics operations, Japanese forces in China faced the constant threat of guerrilla attack. Wherever Japanese were in China, they faced varying degrees of hostility, which put further pressure on supply lines.

In Conclusion

The stories of the Japanese Imperial Army units in Nanking, China, in one respect are not unique in the study of man’s treatment of his fellow man during war. Soldiers as individuals or in small groups have committed atrocities in all conflicts down through the ages. What happened in Nanking was a spontaneous outbreak of incredible violence and brutality, and it says a great deal about the Japanese military and culture at the time that it was allowed to go on for so long.

The Japanese generals who took time out to toast the early success of their China campaign in 1937 drew their jubilation not only from the quick rout of the numerically superior enemy but also from deep cultural roots. By the very act of fighting, they were fulfilling the ancient role of the samurai––the medieval warrior whose fate was conquest or death. The Japanese warriors in China found plenty of both.

Within two years after they swarmed over the Great Wall from attack points in occupied Manchuria, the Japanese had swept south and east 1,200 miles. On the way, their 600,000-man force suffered 60,000 casualties and killed two million Chinese. Among those killed were civilians, butchered in a distinctly un-samurai-like orgy of murder at Nanking.

On November 1, 1948 Japanese General Iwane Matsui, commander in chief of the Central China Area Army, which included the Shanghai Expeditionary Force and the Tenth Army, was indicted by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and convicted of Count 55, “Deliberately and recklessly disregarded their duty to take adequate steps to prevent atrocities.”

The verdict read: “Before the fall of Nanking, the Chinese forces withdrew and the occupation was of a defenseless city. Then followed a long succession of most horrible atrocities committed by the Japanese Army upon the helpless citizens. Wholesale massacres, individual murders, rape, looting, and arson were committed by Japanese soldiers. Although the extent of the atrocities was denied by Japanese witnesses, the contrary evidence of neutral witnesses of different nationalities and undoubted responsibility is overwhelming. This orgy of crime started with the capture of the City on the 13th of December, 1937 and did not cease until early in February 1938. In this period of six or seven weeks, thousands of women were raped, upwards of 100,000 people were killed, and untold property was stolen and burned.

“At the height of these dreadful happenings, on the 17th December, Matsui made a triumphal entry into the city and remained there from five to seven days. From his own observations and form the reports of his staff, he must have been aware of what was happening. He admits he was told of some degree of misbehavior of his Army by the Kempetai and by Consular Officials. Daily reports of these atrocities were made to Japanese diplomatic representatives in Nanking, who in turn reported them to Tokyo.

“The Tribunal is satisfied that Matsui knew what was happening. He did nothing, or nothing effective, to abate these horrors. He did issue orders before the capture of the city enjoining propriety of conduct upon his troops, and later he issued further orders to the same purport. These orders were of no effect, as is now known, and as he must have known. It was pleaded in his behalf that at this time he was ill. His illness was not sufficient to prevent his conducting the military operations of his command nor to prevent his visiting the city for days while these atrocities were occurring. He was in command of the Army responsible for these happenings. He knew of them. He had the power as he had the duty to control his troops and to protect the unfortunate citizens of Nanking. He must be held criminally responsible for his failure to discharge this duty. The Tribunal holds the accused Matsui guilty under Count 55.”

General Iwane Matsui was sentenced to death and hanged on December 23, 1948. The verdict of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East provided to the world the proof of the atrocities committed and denied by the Japanese Army.

The history of Nanking has been altered over time to meet the needs of changing societies in different sociopolitical contexts. Though the details and the number of deaths continue to be debated, most historians agree that the Nanking massacre was an atrocity, in which 370,000 or more Chinese civilians and surrendered soldiers were killed and tens of thousands of women raped following the Japanese capture of the city. Some publications in Japan seek to deny or greatly minimize this event; a term like “so-called” is often placed in front of one of these names. Some seeking to link the event rhetorically or structurally with the more widely known Holocaust in Europe during World War II use the term “Nanking Holocaust.”

It is acknowledged that this was the worst atrocity by the Japanese but there were a number of others, though on a smaller scale. Most notable was Manila in Feb-March 1945 when Gen. Yamashita evacuated with his troops to the mountains and the Naval commander was left in charge. He promptly began a wholesale massacre of civilians and the destruction of the city. Best estimate of the dead are at least one hundred thousand but there were probably more as a number of people from the provinces had fled to the city to escape the fighting with the approach of American forces. There were also massacres in other parts of Japanese occupied areas involving civilians and military prisoners. The best known was the massacre on Palawan Island of over a hundred American POWs and the killing of an almost equal number of civilian contractors after the Japanese took Wake Island. The occupation of parts of China was especially brutal. Only a few Japanese were executed for war crimes despite a wide spread policy carried out by the army. Probably the highest raking official to escape punishment was the emperor who was left untouched by the allies for political reasons. His knowledge of actions by his forces in the field is almost certain and is confirmed by the fact that he destroyed his diaries before his death.

I hadheard the Japanese were brutal and had little respect for life.

Excellent article. However, I am at a loss to know why the author omitted the most horrific crimes the Japanese inflicted on the Chinese population. In thier quest to expand their germ and biological warfare, the Japanese committed the most despicable and unspeakble experiments on live Chinese prisoners and citizens. The camps are now known as the Auchwitz of the East. After world War II, the Japanese scientists, doctors and nurses were tried and convicted of atrocities against humanity. But Gen. MacArthur commuted or shortened their sentences in exchange for the files the Japanese held. These files were then used to further the American quest for their own biological and germ warfare.

The author was not asked to include Japanese Unit 731 in this story. You’ll find a story about Japan’s biological weapons work here:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2015/08/05/military-intelligence-japans-bw-group/

The Japanese treated their Russian POWs quite well during the Russo-Japanese war, also treating their German POWs very well during WWI. In the end, it took US nuclear weapons and Allied occupation to break the back of Japanese militarism. Agree not enough Japanese war criminals were even tried, let alone punished.