By Joseph Frantiska Jr.

What do Pablo Picasso, the U.S. Navy, the British Royal Navy, and the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) have in common?

They were all users of rather distinctive—some would say garish—painting styles. In Picasso’s case, it was to create art. In the military’s case, it was to disguise ships and aircraft with what is known as disruptive or “dazzle” camouflage.

The word camouflage is derived from the French word camoufler, which means to disguise. Draping a white bedsheet over a tank or artillery piece in a snowy landscape is an obvious example of camouflage. So is clothing a soldier in a color-splotched uniform or affixing leaves to his body and helmet to help him blend in with his surroundings.

But painting a ship in contrasting colors, irregular geometric shapes, zigzag lines, and bold black and white stripes seems to go against common sense. This technique was not the brainchild of some naval strategist or a grizzled veteran of the seas but that of British artist Norman Wilkinson, who is credited with inventing dazzle camouflage in time for the Great War. Another artist, John Graham Kerr, also vied for the honor of being the father of the concept, but a court declared Wilkinson the true inventor.

Separately, in the United States, two artists, Abbott Thayer and George de Forest Brush, conducted groundbreaking research into camouflage in the late 1800s, focusing on certain aspects of the protective coloration of plants and animals.

Mother Nature also uses various colors and patterns to make certain birds and animals appear differently and fool the predators that feed upon them. For example, a bird that with blue and yellow coloring—or even a parrot with red, green, and violet coloring—appears as dull gray at a distance of 100 feet. (One hundred feet is the range at which the human eye loses its ability to separate the three color cues.)

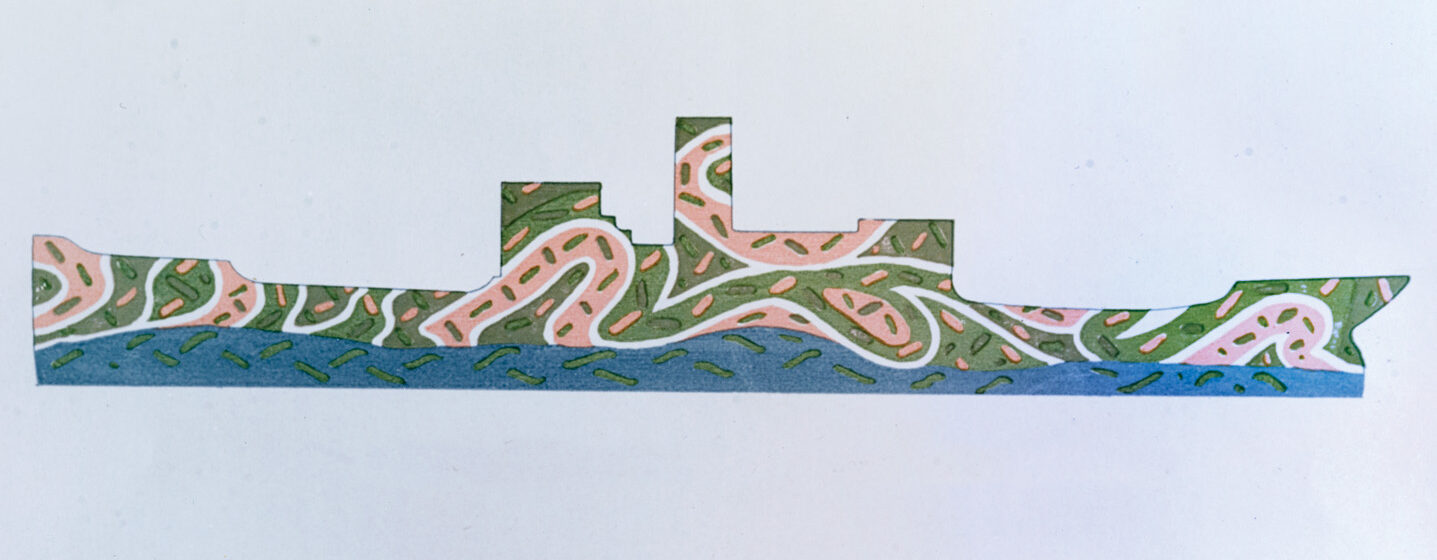

Exploring this principle, Thayer and Brush proposed using countershading to paint ships with patterns derived from this methodology. They found that a vessel could be painted in green wavy lines from the water line and running upward for about 20 feet; above that a combination of red, green, and violet covering upper portions of the hull—as well as the lifeboats, masts, and funnels—seemed to make the ship “disappear.”

Thayer and Brush continued their camouflage experiments as a team and individually as World War I unfolded. Their proposal to the U.S. Navy to adopt their countershading methods to camouflage ships was approved for use on American vessels. A group of their followers recruited hundreds of artists to join the American Camouflage Corps, which had been formed in 1917.

Another major developer of U.S. ship camouflage during World War I was William Andrew Mackay, head of the New York District of the Emergency Fleet Corporation’s camouflage section. It was his responsibility to supervise the artists who applied camouflage patterns to merchant ships in that district’s harbors.

Mackay’s approach to camouflage was derived from the fact that what we see as white light is actually composed of many colors. School children in science class often experiment with clear prisms which, when held at the proper angle to a light source, expose the light’s many colored elements. Of course, in nature the same phenomenon is seen when suspended water particles in the atmosphere create a rainbow.

If the hull of a vessel at sea absorbs some portions of the color spectrum and therefore prevents them from reaching the eye of an observer, that hull or other object will not be sharply defined to the observer. Mackay discovered that red, green, and violet light rays are absorbed by a vessel’s hull. When applied to the sides of a ship, these colors make the hull less visible than a similar one painted in a solid color.

A series of ship camouflage experiments based on Mackay’s research were conducted by the Navy. In one scenario an appropriately camouflaged oil tanker, when seen from three miles away, was said to have “seemed to melt into the horizon.”

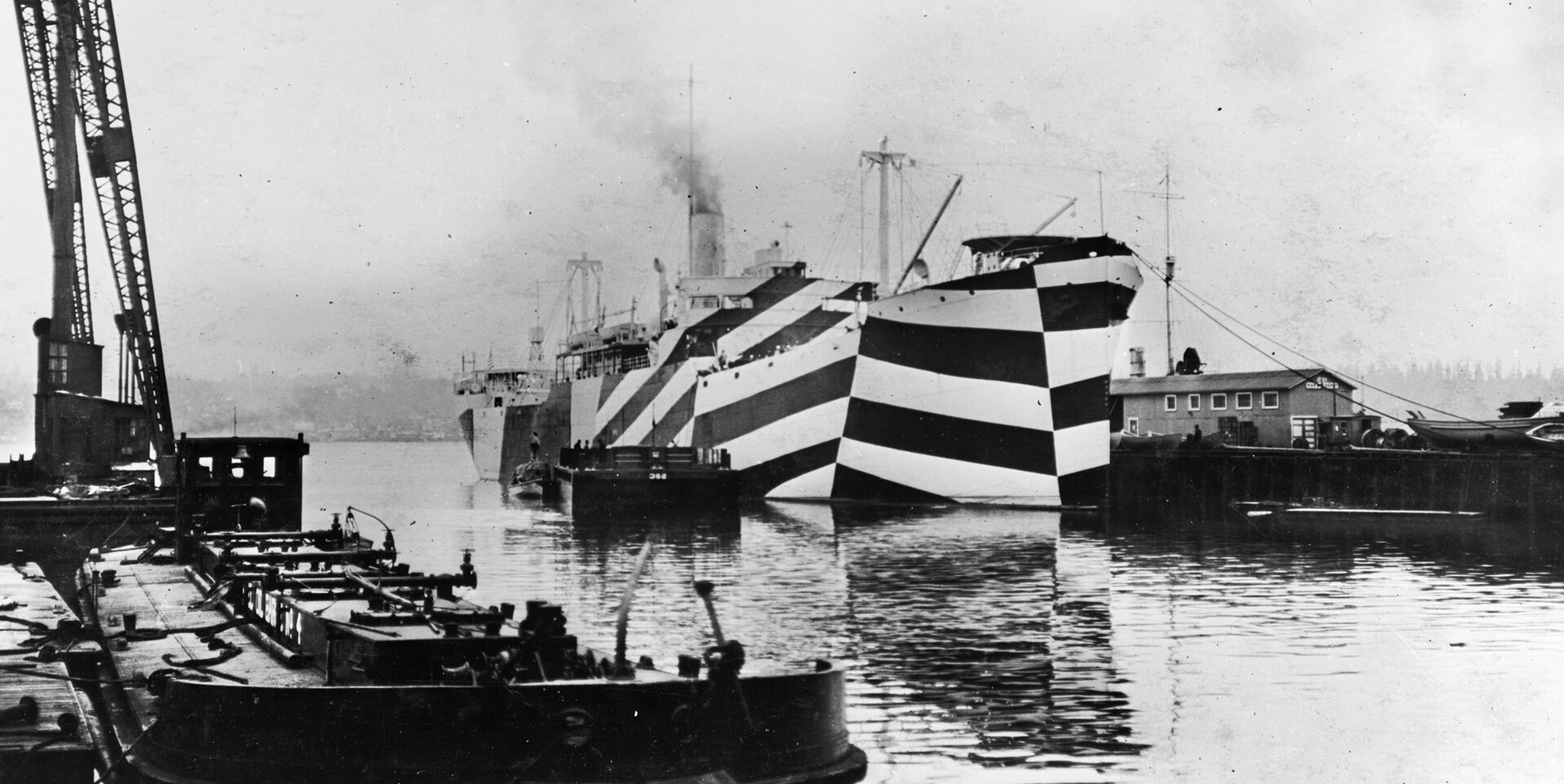

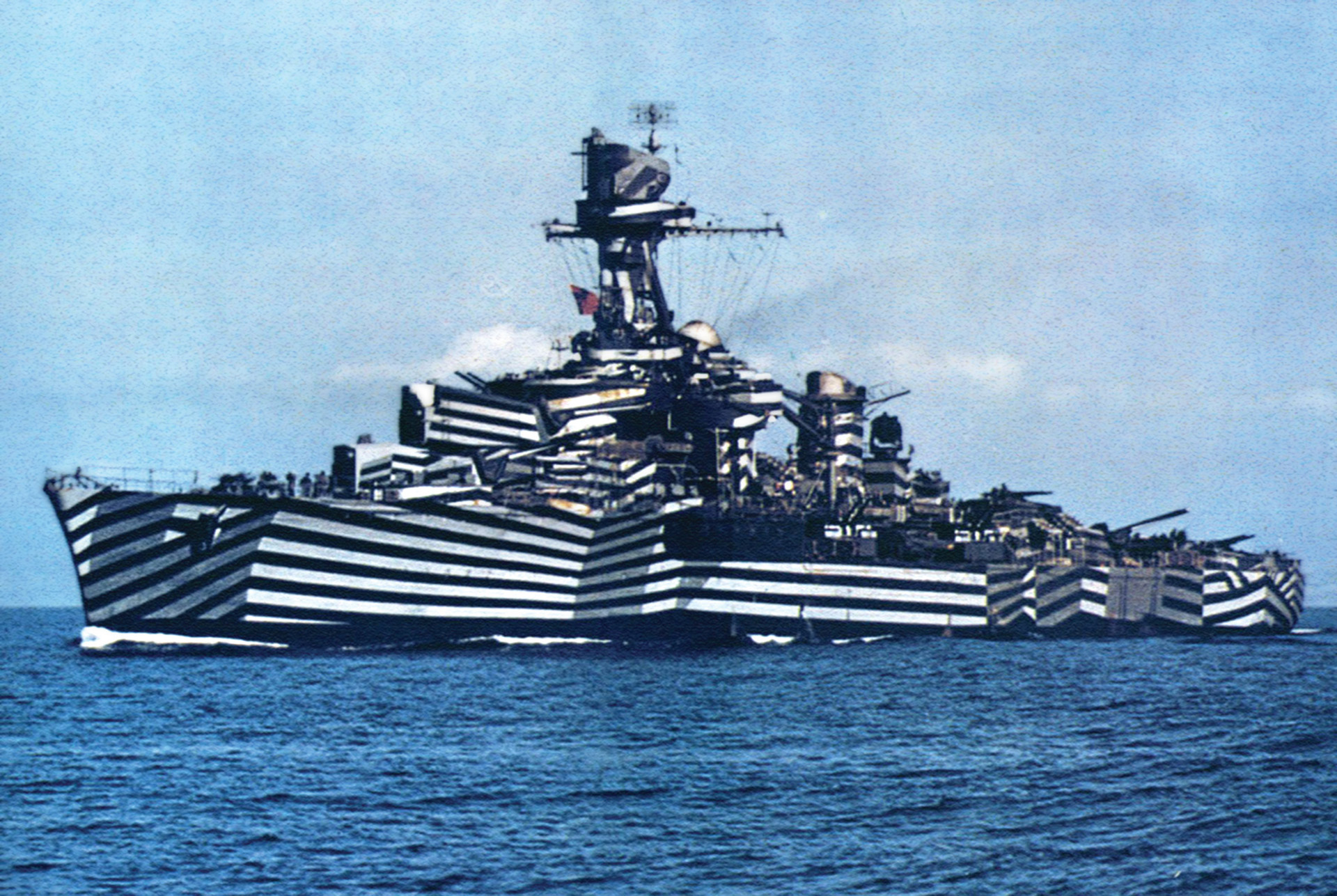

Next came the concept of “dazzle.” Although it seems beyond the realm of common sense, using what the British called “dazzle” camouflage—and the Americans called “razzle-dazzle”—was surprisingly effective.

One example of dazzle camouflage was the SS Osterley, a 12,129-ton British ship built in 1909. In June 1917 she was requisitioned as a troop transport and painted with zebra-like black and white stripes. Despite German U-boats, she came through the war unscathed and returned to commercial service in January 1919, leading a comparatively uneventful life until being scrapped in 1930.

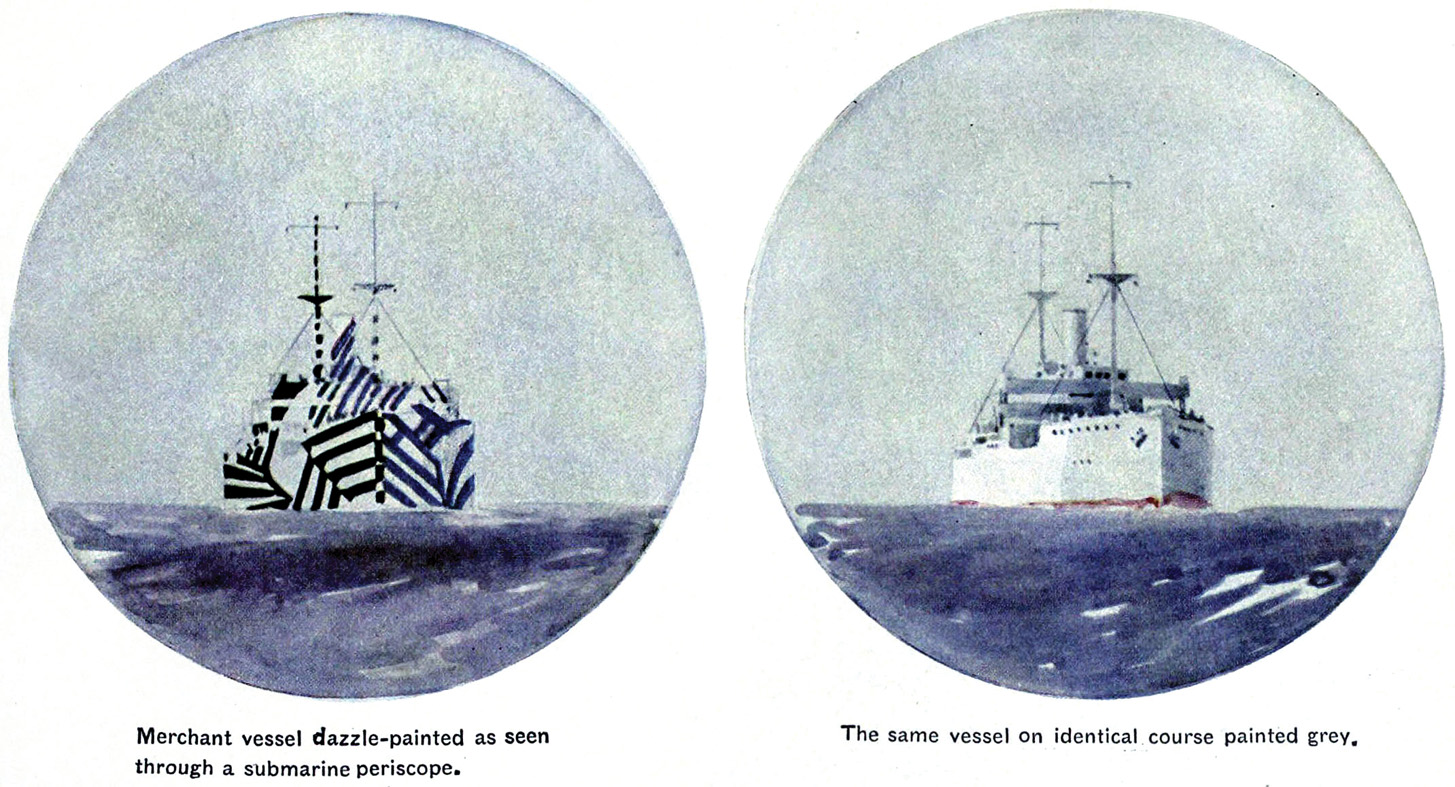

The intent of dazzle was not to hide a ship or plane but rather to make it difficult for the enemy’s rangefinders to determine with certainty its type, speed, and course.

The devices used to make this determination for the big guns of a shore battery or a battleship were visual rangefinders. An observer using a visual rangefinder needs to determine whether the target vessel is approaching or moving away, or whether the bow or stern is being viewed. The disruptive nature of dazzle made this difficult.

The most popular type of rangefinder used at the time was called a coincidence rangefinder. It was composed of a long horizontal tube on a stand with a prism at each end. One of the prisms was fixed at an angle of 45 degrees so that the light coming in would reflect into the device at 90 degrees while the other prism angle was adjustable.

After training the lenses on a potential target, the observer peered into a single eyepiece and saw two half images (upper half and lower half) of the target, with each prism contributing one of the half images. The observer manipulated controls so that the half-image from the adjustable prism lined up with the half-image from the fixed prism to form a complete picture.

The range to the target was then calculated by a trigonometric solution based on the prism angles and the length of the rangefinder known as the Pythagorean Theorem. As the technology improved, some rangefinders were of progressively larger size. Known as large base length rangefinders, they more precisely focused on distant targets.

Dazzle attempted to make this difficult since the wildly irregular patterns when seen in the two halves were hard to align precisely to give an accurate estimate. This also impacted submarine warfare as subs incorporated similar rangefinders into their periscopes. The addition of a waterline pattern made to resemble a false bow wave was intended to make the calculation of a ship’s speed problematic.

While dazzle camouflage proved rather effective in World War I, this low-tech methodology became less useful as high-tech devices such as more complex, accurate rangefinders and eventually radar became increasingly effective as World War II approached.

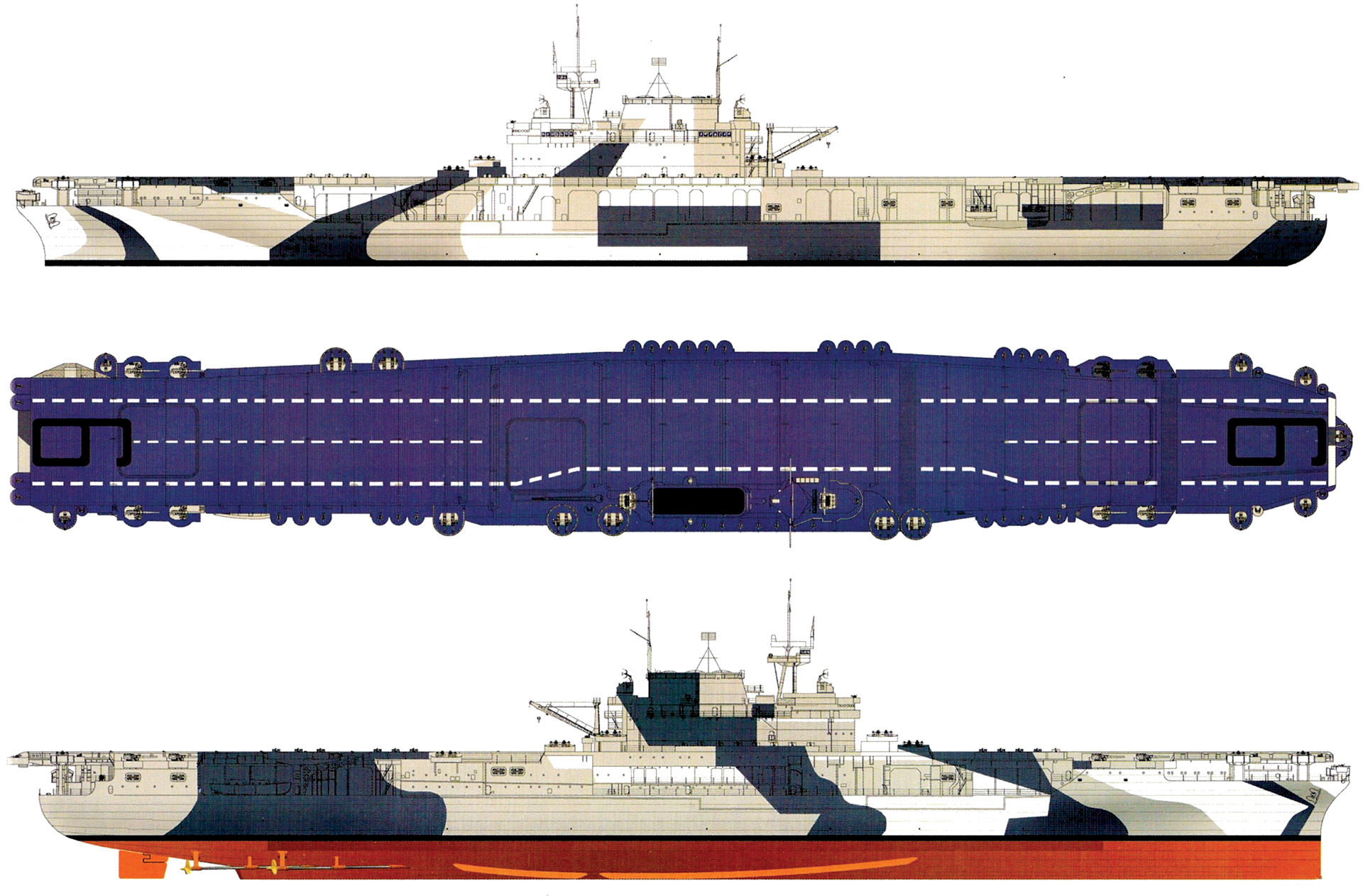

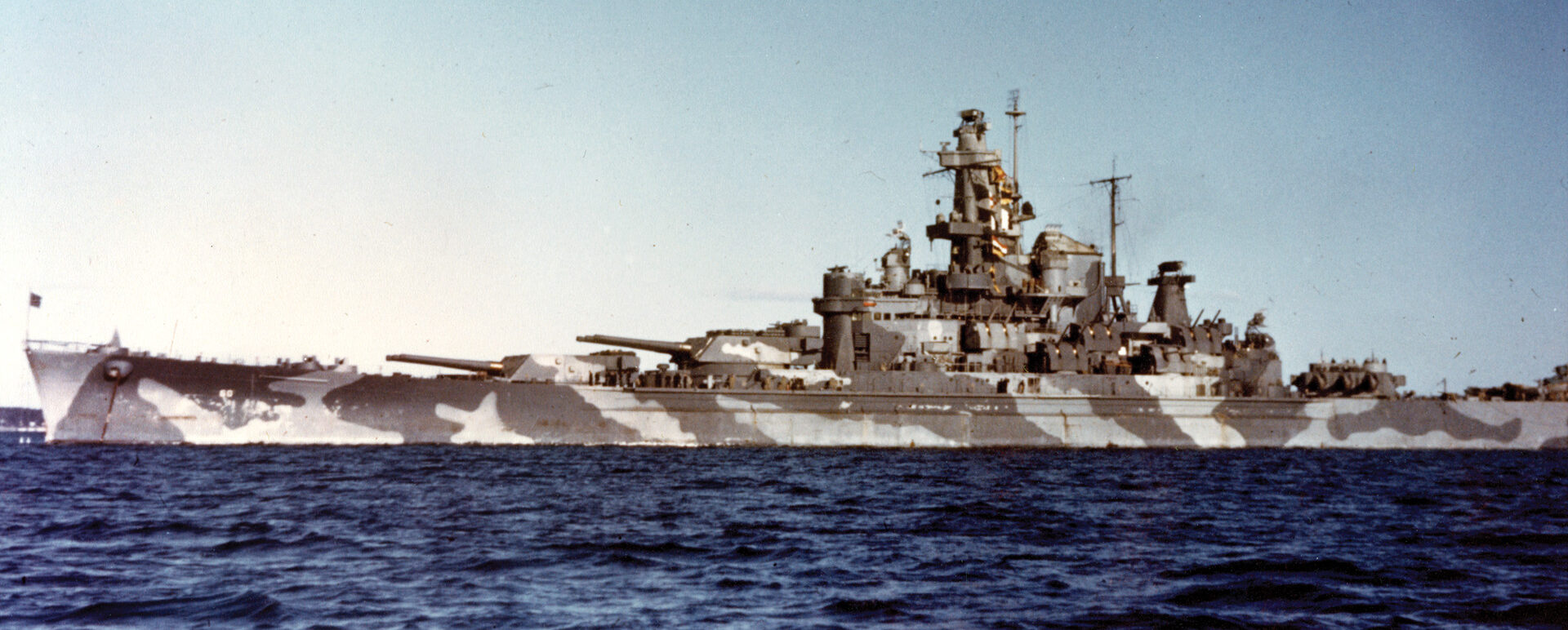

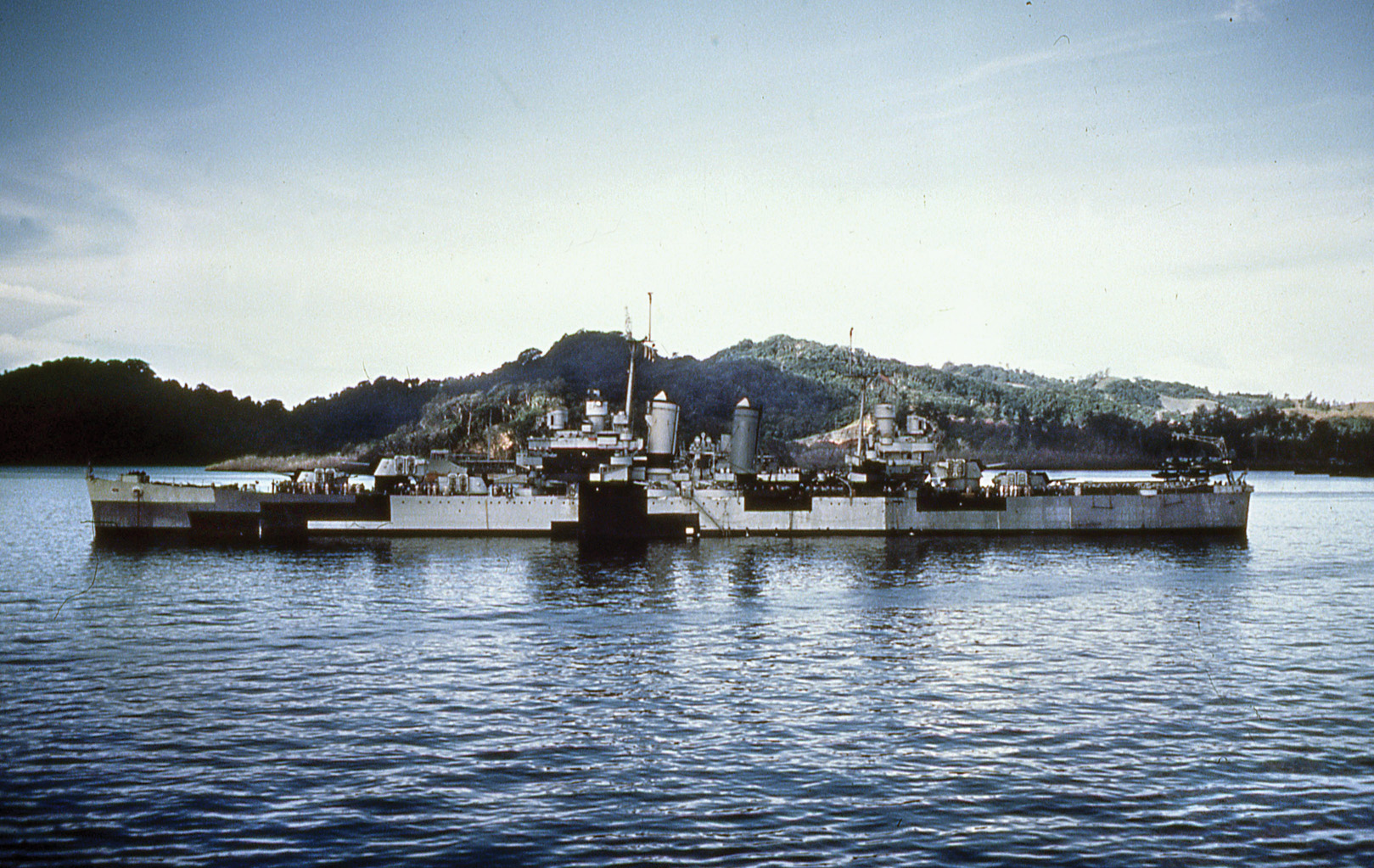

Building on the World War I experience, navies continued to camouflage their vessels during World War II, which would see the most extensive usage of camouflage, dazzle and otherwise. With a degree of deception that could still confuse the less sophisticated periscopes of submarines, the U.S. Navy applied dazzle camouflage on all Tennessee-class battleships and some Essex-class aircraft carriers.

The designs were standardized in a highly structured process by which they were developed, reviewed, and then implemented throughout the fleet. These designs used color combinations called “measures.” They were also meant for transport ships as the Navy sent dazzle plans to the U.S. Shipping Board, which was the precursor to the Merchant Marine.

For example, Measure 32 was a series of asymmetrical geometric patterns employing polygons and stripes of either Black and Ocean Gray, or Black, Ocean Gray, and Haze Gray. Horizontal surfaces were painted with patterns in Ocean Gray and Deck Blue on their upper sides with countershading on their undersides in Pale Gray or White to reduce shadowing. Patterns were also employed at the bow to disguise the bow wave and at the aft to blend in with the wake.

Another example is Measure 33, which was initially created for the carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) in February 1944. The colors for vertical surfaces were Navy Blue, Haze Gray, and Pale Gray, with the color for the horizontal surfaces being Deck Blue.

As World War II wore on in the Pacific, Japanese air power had been largely eliminated, but the threat of enemy submarines remained. To confuse Japanese sub commanders peering at American ships through their periscopes, the U.S. Navy reintroduced dazzle painting to protect the fleet.

However, technology gradually superseded the human eyeball as primitive radar and sonar sets became more capable. Ultimately, there was no need for submarine commanders to visually sight their targets. Thus, the primary purpose of dazzle camouflage was eliminated, and U.S. warships were given a Haze Gray color scheme.

Other nations also employed dazzle camouflage. A striking example of French dazzle camouflage was the Gloire, one of a class of six light cruisers that France completed before World War II. Gloire and two of her sisters were sent to Dakar to join the fleet assembled around the battleship Richelieu. Gloire served with Force L, based at Brest at the beginning of the war and afterward with Vichy French forces.

After the Vichy collapse, Gloire returned to the Mediterranean on the Allied side and participated in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France, in August 1944. At war’s end, she moved to the Far East in the reoccupation of French Indo-China. She was scrapped in 1958.

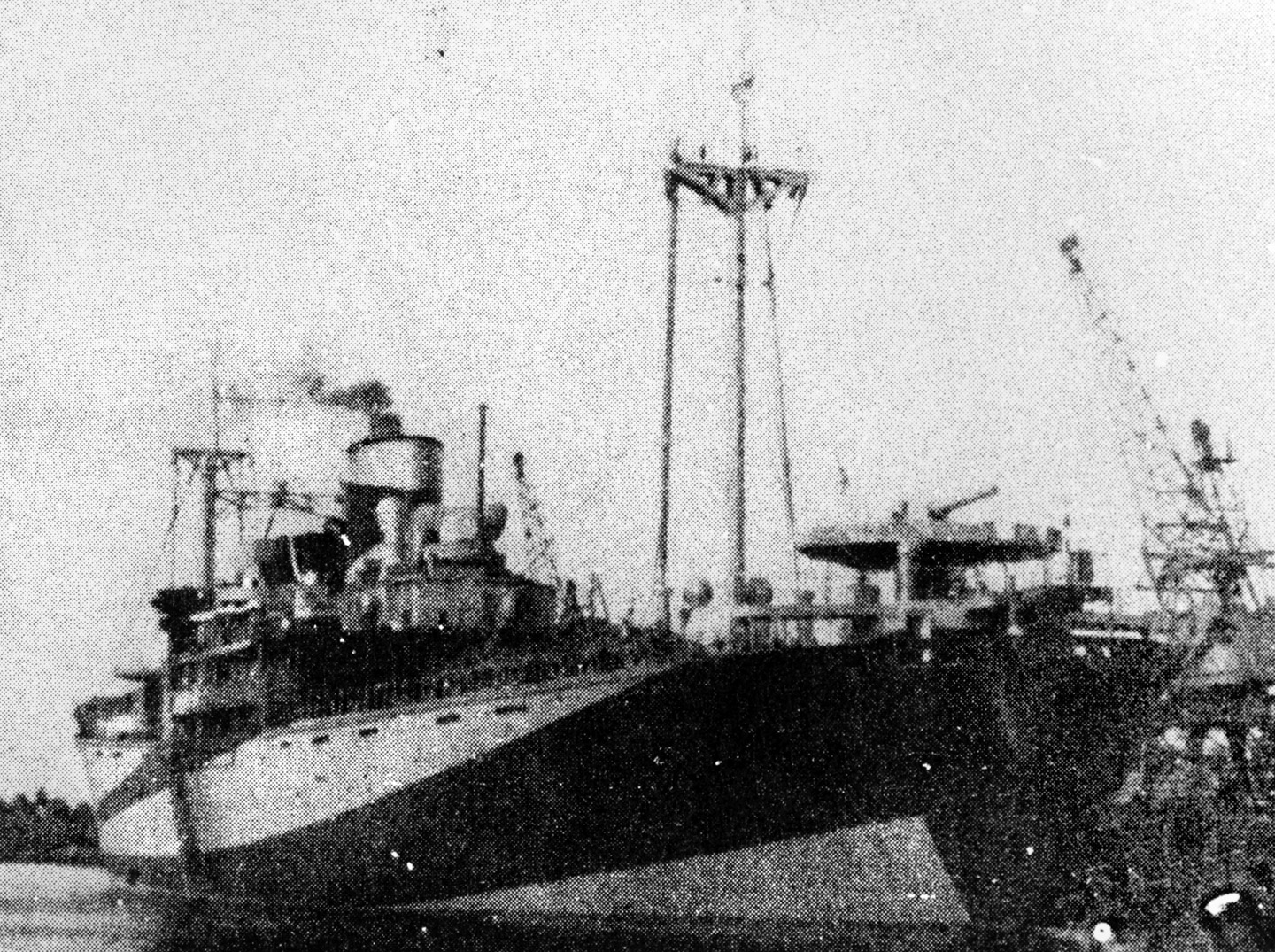

Japan also used dazzle camouflage in World War 1 to protect its ships. One vessel thus painted was the Tottori Maru, a 5,973-ton, 423-foot-long passenger-cargo ship. On October 15, 1918, it was fired upon by a German submarine, which unleashed two torpedoes at it that missed their target by a few feet ahead of the ship. The ship’s captain strongly felt that the dazzle camouflage played a significant part in the saving of his ship.

What looked from a distance like the bow of the ship was actually part of the camouflage scheme, while the real bow was several feet ahead. Therefore, the actual and apparent courses of the ship appeared to be different. The captain concluded that the torpedoes were set to hit the ship on its apparent course and this is why they missed.

The saving of the Tottori Maru and its crew sealed the fate of many Americans in World War II as she was pressed into service as one of the infamous Japanese “hellships” in which prisoners of war were transported to prison camps.

Tottori Maru’s luck finally ran out on May 15, 1945, when the U.S submarine Hammerhead (SS-364) sank her in the Gulf of Siam as she was bound for Singapore. Whether or not dazzle camouflage would have saved her is a moot point. Fortunately, no POWs were on board.

The use of dazzle camouflage for Japanese ships was the result of the experimentation and research by Lt. Cmdr. Shizuo Fukui, who developed the following ship camouflage principles:

1. To break up sharp angles, use black and white diagonal lines.

2. To keep the contrast of light and shadow at a minimum, apply dark gray to curved surfaces, since in shadow the gray appears very dark and in sunlight it does not reflect light.

3. Apply white to the entire bow area to conceal the bow wave, which will make it difficult to judge the ship’s speed.

4. Apply white to the top of the funnel to make it appear shorter.

5. Create converging lines on the funnel to make a raked funnel appear vertical.

6. Camouflage the after and forward sections of the bridge to make it appear as if it were in the same plane as the ship’s hull, thus making it difficult to ascertain the ship’s heading. Removing a definitive background increases the difficulty in judging the angle or planes of various ship sections.

7. The camouflage gives its best effect when seen at an angle of 30 to 60 degrees from the ship’s bow.

The Sagara Maru was a 7,189-ton seaplane carrier/tender and former Nippon Yusen Kaisha type S high-speed cargo ship. Its captain requested that Lt. Cmdr. Fukui apply his dazzle camouflage techniques to the ship after it arrived in Singapore in February 1942. Intending to use black and white, Fukui was implored by the captain to substitute a light gray instead of white since white was the color of death. These colors were applied in the same pattern to both the port and starboard sides of the ship.

Orders were given to captains of all other ships to submit reports when sighting the Sagara Maru. The reports indicated that the camouflage scheme was the best seen up to that time, so other Japanese Army transports in the area soon copied it. But the Sagara Maru’s fate was soon to be sealed.

On the July 4, 1943, off Honshu, the Sagara Maru got into a duel with the submarine USS Pompano (SS-181), and the Japanese transport lost. Sagara Maru was abandoned as a total loss and stricken from the Japanese Navy list.

At the start of World War II, the German Navy (Kriegsmarine) became aware of the Allies’ extensive usage of camouflage for their maritime fleet. It, too, began to use dazzle camouflage on some of its ships, starting with the 1940 Norway campaign.

Instead of employing dazzle, the Kriegsmarine used the distinctive patterns to make the ships blend into the background of Norway’s rocky and snow-covered cliffs. On January 14, 1942, the battleship Tirpitz set sail from Wilhelmshaven to Norway. She was to attack convoys bound for the Soviet Union, tie down British naval assets, and deter a major Allied invasion of Norway.

After a short stop at Trondheim, she moved north to the Faettenfjord. There she was moored close to a cliff to protect her from air attacks from the southwest.

Instead of sporting dazzle camouflage, however, Tirpitz operated in the Standard Light Gray 50 and Medium Gray 51 patterns with Dark Gray turret tops and gun barrels. To conceal her from air attacks, her crew cut down trees and branches and placed them on Tirpitz’s deck and superstructure and overlaid parts of the ship with canvas.

Moored at Faettenfjord for eight months (Hitler did not want his capital ships sailing the oceans for fear that they would meet the Bismarck’s fate––she was sunk on May 27, 1941), Tirpitz’s crew endured monotony and boredom as fuel shortages reduced training and kept her and her escorts in place behind their protective defenses. The crew was occupied with maintaining Tirpitz and constantly manning the antiaircraft batteries.

Remaining at Faettenfjord until October 29, 1943, Tirpitz was attacked four times by the RAF with limited success. Due to the concentration of antiaircraft weaponry on the ship and the surrounding area, the RAF lost 12 bombers in the attacks. Tirpitz was finally sunk by British carrier aircraft on November 12, 1944.

In addition to using dazzle camouflage to deter the enemy from accurately tracking the Third Reich’s capital assets, the German military forces used rangefinders to locate enemy forces. However, instead of the single eyepiece coincidence rangefinder, they largely employed the two-eyepiece stereoscopic rangefinder to determine the distance of a target.

The stereoscopic rangefinder utilized stereoscopic vision so that the user peered through the eyepieces that were fitted with special reticles. By superimposing the stereoscopic images formed by the pair of reticles over the images of the target seen in the eyepieces, the range was obtained when the reticle marks appeared to be suspended over the target and at the same apparent distance.

A stereoscopic range finder uses two eyepieces, as do binoculars, and relies on the visual portion of the operator’s brain to merge the two images together. Each eyepiece contains a reference mark. The operator first centers the mark on the target, then rotates the prisms until the marks overlap into a combined image. The target’s range is directly related to the amount of prism rotation.

Ships were not the only vehicles that were camouflaged with garish patterns in hopes of concealing their position or movement. Aircraft were also used as canvases for these designs.

The foremost practitioner of this craft in the United States was McClelland Barclay. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1891, he received his education at several prestigious art schools.

How did one of America’s finest illustrators become associated with the U.S. Navy? In 1917 Barclay won the Navy Poster Prize from the Committee on National Preparedness for his poster, “Fill the Breach.” The following year, he worked on naval camouflage under William Andrew Mackay. After a 20-year absence, Barclay renewed his connection with the Navy in June 1938, when he was appointed assistant naval constructor with the rank of lieutenant in the Naval Reserve.

In 1940, Barclay created dazzle camouflage designs for various types of naval combat aircraft with hopes that he would replicate his success with ships. However, evaluation tests showed that dazzle camouflage was of little use for aircraft due to their greater speed and closer distance.

In a change of direction, Barclay offered his talents to the Navy’s New York recruiting office in October 1940 and designed some of the most popular World War II naval recruiting posters over the next 21/2 years. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, he volunteered as a combat artist. Not accepted by the Combat Art Section, he returned to designing recruiting posters.

But not content to sit in a studio painting portraits and imaginary battle scenes, Lt. Cmdr. Barclay gained firsthand knowledge on short tours of duty in the Atlantic and the Pacific aboard the battleships USS Arkansas, Pennsylvania and Maryland and the light cruiser Honolulu.

In July 1943, Barclay was aboard LST-342 off the Solomon Islands, sketching and taking photographs. At 1:30 am on July 18, the craft was struck by a Japanese torpedo and blown in half, killing Barclay and several others. Barclay was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Art Directors Club Medal in 1944,“in recognition of his long and distinguished record in editorial illustration and advertising art, and in honor of his devotion and meritorious service to his country as a commissioned officer of the United States Navy.” He was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1995.

There has been something of a recent return to the angles, colors, and lines of dazzle camouflage. The USS Freedom (LCS-1) is the first of America’s new littoral combat ships. Its mission is to engage the enemy in comparatively shallow areas that are close to shore as a fast, maneuverable, and relatively inexpensive vessel.

Freedom’s commanding officer felt that a different scheme from the standard gray would help to make the ship’s approach direction and angle more difficult for an enemy to judge. Dazzle Measure 32 was found to suit the task, and it was applied. In tests the ship’s activities were difficult for others to ascertain under various conditions.

It seems that dazzle camouflage may live on after all.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments