By Jessica J. Sheets

At nightfall on October 14, 1781, 150 British and Hessian soldiers sheltered in two small earthen fortifications at Yorktown, Virginia. Across the field from the two redoubts waited 800 Continental soldiers and their French allies. There was no moon. Silence—or rather “Rochambeau”—was the watchword of the night.

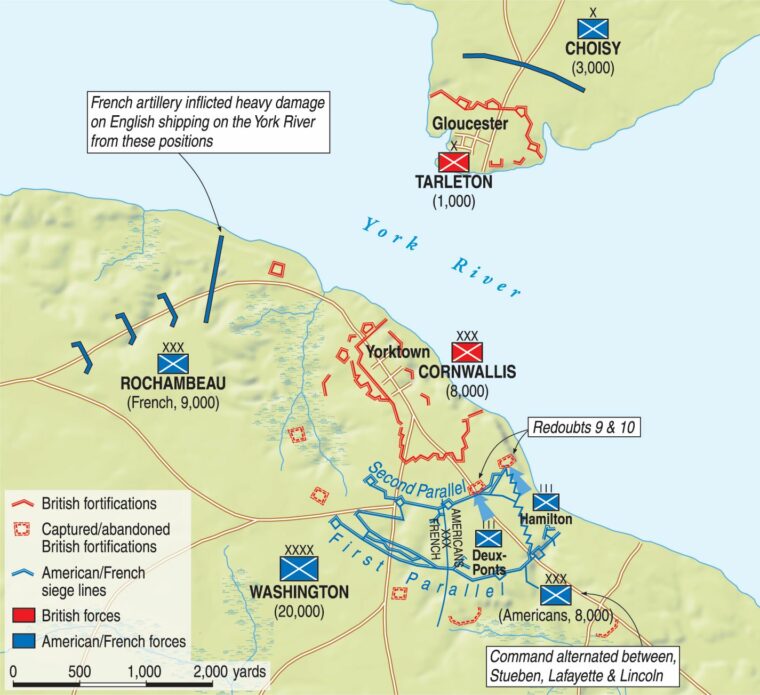

Yorktown, established in 1691 as a port along the York River just off the Chesapeake Bay, stirred with commerce when the Revolutionary War began in 1775. In the spring and summer of 1781, British General Lord Charles Cornwallis raided areas of Virginia in order to reduce the amount of supplies and food being provided by the state for the Continental Army. Meanwhile, General Sir Henry Clinton, the overall British commander in North America, ordered Cornwallis to capture a coastal area where British ships could harbor safely. In early August, Cornwallis took Yorktown and Gloucester Point, a peninsula a half mile across the river from Yorktown. There ships could easily maneuver in the deep water of the York River, while the bluffs along the Yorktown shore would intimidate potential invaders. The terrain outside town provided reasonable defense, but fortifications would also be necessary.

Cornwallis had his soldiers, as well as slaves who had been promised freedom for their service to the crown, build a defensive line surrounding Yorktown. The general believed that Yorktown could be fortified in six weeks. Since no immediate threat existed, the men labored slowly in the oppressive heat. Captain Johann Ewald of the Hessian Field-Jäger Corps had been in Virginia for months. He described the heat as “so unbearable that many men have been lost by sunstroke or their reason has been impaired. Everything that one has on his body is soaked as with water from the constant perspiration.”

The British soldiers and slaves felled trees, tore down houses, set up artillery batteries, and constructed trenches and redoubts. They did their work with spades, shovels, pickaxes, hatchets, and wheelbarrows. The men had difficulty building the earthworks because of the sandy soil. Nonetheless, the redoubts that eventually took shape would serve as defensive outposts to help the British hold Yorktown. Redoubts 9 and 10 were constructed on the left of the British line, southeast of Yorktown. Redoubt 10 stood closest to the York River, with Redoubt 9 about 300 yards southwest. The two redoubts shared certain features—palisades, fraises, and abatis—but they were of different shape and size. Redoubt 9, a pentagon, was 103 yards in perimeter. Redoubt 10 was square and somewhat smaller than Redoubt 9.

In the 18th century, principles for constructing fortifications and conducting sieges followed the designs and doctrine set forth by Sebastien le Prestre de Vauban, a Frenchman who served under King Louis XIV. During the Revolutionary War, manuals espousing Vauban’s techniques included The Field Engineer of M. le Chevalier de Clairac by Louis Andre de la Mamie, Chevalier de Clairac, and An Essay on Field Fortification by J. C. Pleydell.

Redoubts could be square, pentagonal, hexagonal, or circular in shape and could be sized to hold a small or large number of men. A square redoubt with a 40-yard interior perimeter required 80 men for its defense, while a square redoubt of 120 yards interior perimeter required three times as many men. The entrance was placed on the side away from the enemy. Redoubts were surrounded by a ditch, which ideally was at least six feet deep. The sides of a ditch were sloped, with sharpened logs called palisades placed close together and vertically. Palisades typically stood as tall as a soldier.

Dirt from the ditch was used to form the parapet—the mound of earth that formed the perimeter of the redoubt and protected the men inside from enemy fire. Parapets were usually higher than the soldiers, which helped keep the men inside from being seen. In his manual, Clairac recommended fixing the elevation at 7½ feet, with a 12-foot thickness if cannons were involved. A firing step against the interior of the parapet, called a banquette, allowed men to look over the parapet and shoot. Openings called embrasures were made in the parapet for artillery to fire through. Pointed logs called fraises, placed at an angle near the outside base of the parapet, pointed over the ditch. “Fraises are made eight feet long, and five inches broad, sharp at one end. Two men may make twelve fraises in an hour,” Pleydell wrote.

Other items soldiers might build for redoubts included abatis, gabions, fascines, and sods. Abatis consisted of hewn trees with the points of their branches turned toward the enemy. They were placed before the ditch. Gabions, basket-shaped devices from one to three feet high, were made of intertwined twigs and branches. To provide

support for a parapet, men placed gabions at its base and piled dirt into and over them. Gabions, and sometimes sand bags, were also placed on top of a parapet to provide more cover for soldiers. Fascines, bundles of tree branches, were laid against the parapet and secured with stakes to keep the soil stable. When a ditch was in a line of attack, lead soldiers would fill the ditch with fascines to help troops cross the ditch more easily. Lastly, a parapet might be covered with brick-shaped sods to keep the earth in place.

While the British soldiers and slaves shoveled sandy dirt to form the earthworks at Yorktown, American General George Washington and his ally French Lt. Gen. Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, remained outside New York City. They deceived Clinton, inside the city, into thinking they would attack. Instead, beginning on August 19, they stealthily moved their troops 450 miles south to Yorktown. The urgent desire to trap Cornwallis at Yorktown was evident in a letter Washington wrote to Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln. “Every day we now lose is comparatively an age. As soon as it is in our power with safety, we ought to take our position near the enemy. Hurry on then, my dear sir, with your troops on the wings of speed. The want of our men and stores is now all that retards our immediate operations. Lord Cornwallis is improving every moment to the best advantage, and every day that is given him to make his preparations may cost us many lives to encounter them.”

Meanwhile, French Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, arrived off the coast of Virginia on August 26 and occupied Chesapeake Bay a few days later. Corporal Stephan Popp, who served in the German Bayreuth Regiment with the British, wrote in his journal on August 26, “A French Fleet has arrived. Day and night we are at work strengthening our lines—have hardly time to eat and little food—but we are getting ready to make a stout defence.” The days of unhurried work were over.

A British fleet under Rear Admiral Thomas Graves sailed from New York and arrived off the Virginia coast on September 5. French ships came out of the Chesapeake to confront them, and a two-hour battle ensued. De Grasse’s 24 vessels inflicted severe damage on Graves’s 20 ships. After the sea battle had claimed some 300 killed or wounded, the British fleet returned to New York. Cornwallis was cut off by the sea.

On September 28, more than a month after slipping away from New York, the main Continental and French army, numbering over 17,000 men, arrived within a couple miles of Yorktown. On the morning of September 30, the Allies discovered that the British, who numbered around 8,000, had abandoned their outermost fortifications and fled to their defenses closest to town. The Allies took over the abandoned redoubts. The British still held Redoubts 9 and 10, approximately 300 yards from the British line, and Cornwallis continued to be confident. He expected Clinton’s promised reinforcements to break through the French blockade and reinforce his troops. American patriot Benjamin Franklin knew better. Cornwallis’s army, he said, “have had the goodness to quit a situation from whence it might have escaped, and placed itself in another from whence an escape was impossible.”

Meanwhile, there was activity across the river at Gloucester Point involving the feared British cavalry leader Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton. British troops under the command of Lt. Col. Thomas Dundas had been posted at Gloucester to help protect the army across the river and forage for provisions. As the siege of Yorktown intensified, Tarleton’s British Legion was sent to Gloucester, where it could be of more use than passively enduring a siege. French forces, including Louis Armand de Gontaut-Biron, duc de Lauzun, and his Legion, joined Virginia militia already at Gloucester to hold the British there. Militia forces stationed around Gloucester Court House were under the command of Brig. Gen. George Weedon. French Brig. Gen. Claude Gabriel de Choisy was given command of all the Allied troops at Gloucester. He intended to threaten the British.

On October 3, the Allies received word that the British were foraging, with Tarleton’s Legion and other cavalry and infantry troops providing protection. The Allies, already heading south to Gloucester Point, intended to confront them. Lauzun stopped at a house and learned from a woman that Tarleton had just been there. Soon the enemies encountered each other at a hook near where two roads met. Tarleton fell from his horse before he could fight Lauzun in the initial attack. Other British troops rushed to his rescue and retreated. The Allied cavalry under Lauzun, outnumbered by the British, had the edge at the moment.

Both sides formed for another attack. Lauzun’s cavalry fought British soldiers along a tree line and were pushed back. Select militia under Lt. Col. John Mercer eventually repelled the British, who retreated to their defenses at Gloucester Point. The Allies had suffered five killed and more than two dozen wounded, while the British suffered greater losses—50 killed or wounded, including Tarleton, who recovered. Washington commended “the brilliant success of the Allied Troops near Gloucester.” Thanks to the Allied victory at the Battle of the Hook, the British at Gloucester would no longer be able to aid their brothers across the river.

Meanwhile, at Yorktown the Allies were busily constructing siege works outside of town. They worked on the first parallel, a 2,000-yard-long trench line along the south side of Yorktown, which included batteries and redoubts. It ran about 800 yards from the British line. On October 7, Allied troops manned the parallel. Continental Sergeant Joseph Plumb Martin, in the Corps of Sappers and Miners, related the reaction of the British to the first parallel: “As soon as it was day they perceived their mistake and began to fire where they ought to have done sooner. They brought out a fieldpiece or two without their trenches, and discharged several shots. They had a large bulldog and every time they fired he would follow their shots across our trenches. Our officers wished to catch him and oblige him to carry a message from them into the town to his masters, but he looked too formidable for any of us to encounter.”

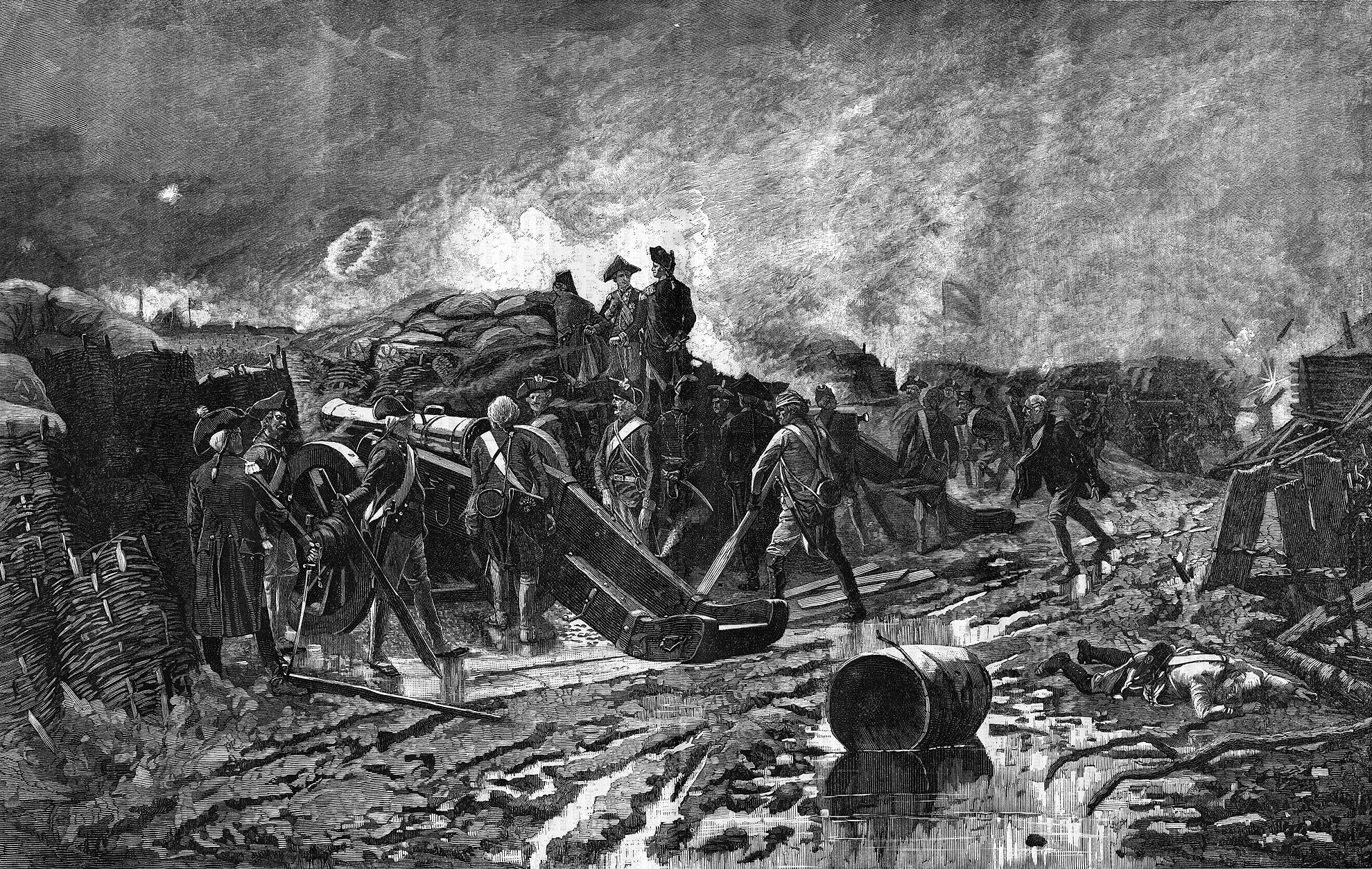

Two days later, the Allies began shelling Cornwallis and his men. The firing was persistent. In his October 9 diary entry, Continental Army Captain Benjamin Bartholomew wrote, “Just as the sun was setting our Battery on the Right and one from the French on the Left opened a most tremendous blaze on the British which continued incessantly all night.” Georg Daniel Flohr, an enlisted German in the French Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment, noted in his journal that “houses stood there like lanterns shot through with cannonballs.” George Washington himself lit the first cannon shot, which passed smoothly through the window of British headquarters and landed on the dinner table where the commissary general and his staff had just sat down to dine. The general was killed, and several officers were wounded when the cannonball bounced directly off their plates.

The British fortifications began to crumble. Construction of a second parallel by the Allies, 750 yards long and 300 yards from the British lines, began on the night of October 11. Lieutenant William Feltman of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment recorded the efforts. “Every second man of the whole detachment carried a fascine and shovel or a spade, and every man a shovel, spade or grubbing hoe,” he wrote. “We dug the ditch three and a half feet deep and seven feet in width.”

But the parallel could not be completed until Redoubts 9 and 10 were taken from the British. “Two redoubts advanced of their lines, and within rifle shot of our second parallel, much in the way,” Major Ebenezer Denny of Pennsylvania wrote in his journal. “These forts or redoubts were well secured by a ditch and picket, sufficiently high parapet, and within were divisions made by rows of casks ranged upon end and filled with earth and sand. On tops of parapet were ranged bags filled with sand.”

Hessian Captain Ewald noted, “Without bragging about my limited perception, I have told everyone that as soon as one of these redoubts is taken the business is at an end, and Washington has us in his pocket. Yet one still hears, ‘But our fleet will come before that time and raise the siege.’” The experienced Ewald had his doubts, as did an unnamed fellow officer who complained: “We get terrible provisions now, putrid meat and wormy biscuits that have spoiled on the ships. Many of the men have taken sick here with dysentery or the bloody flux and diarrhea. Foul fever is spreading. We have had little rest day or night.” Hundreds of skinned and butchered British horses could be seen floating down the York River.

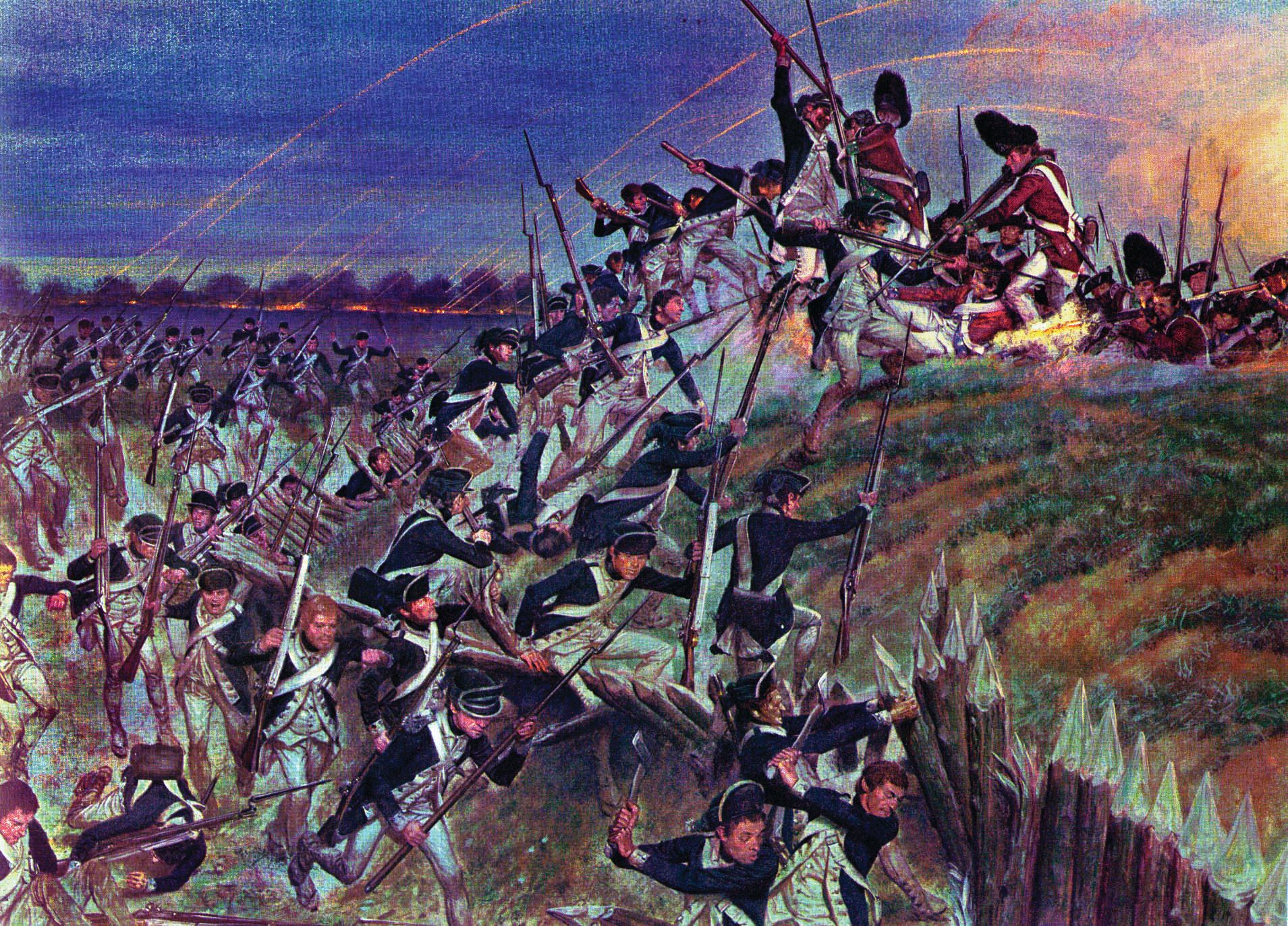

The assignment of capturing the redoubts was given to French Maj. Gen. Antoine Charles du Houx, Baron de Viomenil, and American Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton. On the night of October 14, Viomenil’s troops, led by Lt. Col. Count William de Deux-Ponts, undertook to seize Redoubt 9. A group of grenadiers and chasseurs, trained to overcome defenses surrounding fortifications, went first to clear the abatis. They brought along fascines to fill the ditch and ladders for scaling the parapet. At eight o’clock, the prearranged signal—three successive cannon shots—rose into the night. The attack began.

Deux-Ponts described the advance in his journal. “At a hundred and twenty or thirty paces, we were discovered,” he wrote. “We lost not a moment in reaching the abatis, which being strong and well preserved, at about twenty-five paces from the redoubt, cost us many men, and stopped us for some minutes, but was cleared away with brave determination; we threw ourselves into the ditch at once, and each one sought to break through the fraises, and to mount the parapet.”

Popp, on the receiving end of the attack, entered in his journal on October 14: “The French grenadiers stormed our line, without firing a shot, captured a hundred of our men on the advanced line, killed and wounded those who refused to surrender—made a great noise with their shouting, seized our lines and turned them.” He also noted that they “could distinctly hear and understand the orders given in German to the enemy’s German troops.”

Second Lieutenant Wilhelm Heinrich Florus Graf von Schwerin, in the French Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment, was among the Germans serving with the Allies. He wrote, “At 8 o’clock at night we approached the redoubts, always hidden behind our entrenchments. At 8:15 we were ordered to march in attack step up to the enemy redoubt and ascend it in an assault, our colonel-en-second at the head. There was a very lively fire from all sides for about a quarter of an hour.”

Flohr also described the advance of the soldiers and the ensuing confusion inside: “It was as bright as daylight, but we ignored the firing and kept on marching. Once we got closer to the redoubt and they could reach us with their muskets, they fired so heavily at us from out of the redoubt that we fell just like snowflakes. One could think that it rained bullets. Since we were completely surrounded by the enemy we were almost annihilated. One screamed for help here, the other there. We had to run at a double-quick pace until we finally reached the redoubt and got into the ditch, where we were without protection from the fire out of the redoubt.

“The carpenters cut off the palisades with the utmost speed. As soon as there was a little space, the attack had to be made up into the redoubt. The enemy troops stood on top of the redoubt and had their bayonets lowered against those who wanted to get up. Many had axes to defend themselves with.

“But as the noise was too great, our general could not become master of the situation. The soldiers everywhere were so enraged and excited that our people killed each other. The French … struck down everyone who wore blue coats. Since the Deux-Ponts regiment also wore blue, very many were stabbed to death that way. Some of the Hessian and Ansbach troops wore uniforms almost identical to ours, and the English wore red, which in the dark of night seemed blue as well, and things went unmercifully that night.” According to Flohr, after the struggle for Redoubt 9, “the whole redoubt was so full of dead and wounded that one had to walk on top of them.”

Schwerin, Flohr, and the rest of Viomenil’s 400 men took control of the redoubt from the 120 British and Hessians inside within half an hour. The French suffered 15 killed and more than 70 wounded. Eighteen British were killed, 50 were captured, and the rest escaped.

At the same time, 400 of Hamilton’s Continental troops stormed Redoubt 10. Before they went, Washington spoke to the men. “General Washington made a short address or harangue, admonishing us to act the part of firm and brave soldiers, showing the necessity of accomplishing the object, as the attack on both redoubts depended on our success,” wrote Captain Stephen Olney of Rhode Island. “The column marched in silence, with guns unloaded, and in good order. Many, no doubt, thinking that less than one quarter of a mile would finish the journey of life with them.” They approached with fixed bayonets toward a redoubt held by British troops.

Washington watched the attack on the redoubts through an embrasure cut for the main battery. Generals Henry Knox and Benjamin Lincoln stood beside him. When one of Washington’s aides remonstrated that the commanding general was too exposed, Washington told him scornfully, “If you think so, you are at liberty to step back.” A moment later an English musket ball ricocheted through the opening off a nearby cannon and fell at Washington’s feet. He ignored the spent shot and continued watching the advance.

Sergeant Joseph Martin recounted the swiftly unfolding events: “The Sappers and Miners were furnished with axes and were to proceed in front and cut a passage for the troops through the abatis. At dark the detachment was formed and advanced beyond the trenches and lay down on the ground to await the signal for advancing to the attack, which was to be three shells from a certain battery near where we were lying. We had not lain here long before the expected signal was given. The word up, up, was then reiterated through the detachment. We immediately moved silently on toward the redoubt we were to attack, with unloaded muskets. Just as we arrived at the abatis, the enemy discovered us and directly opened a sharp fire upon us. We were now at a place where many of our large shells had burst in the ground, making holes sufficient to bury an ox in.

“The Sappers and Miners soon cleared a passage for the infantry, who entered it rapidly. Our Miners were ordered not to enter the fort, but there was no stopping them. I therefore forced a passage at a place where I saw our shot had cut away some of the abatis; several others entered at the same place. While passing, a man at my side received a ball in his head and fell under my feet, crying out bitterly. While crossing the trench, the enemy threw hand grenades into it. As I mounted the breastwork, I met an old associate hitching himself down into the trench. I knew him by the light of the enemy’s musketry, it was so vivid. The fort was taken and all quiet in a very short time.”

Captain Olney described the attack as well. “When we came near the front of the abatis, the enemy fired a full body of musketry. At this, our men broke silence and huzzaed; and as the order for silence seemed broken by every one, I huzzaed with all my power. The pioneers began to cut off the abatis. This seemed tedious work, in the dark, within three rods of the enemy.”

Once he got through the abatis, Olney entered the ditch, “and when I found my men to the number of ten or twelve had arrived, I stepped through between two palisades (one having been shot off to make room) on to the parapet, and called out in a tone as if there was no danger, ‘Captain Olney’s company form here!’ On this I had not less than six or eight bayonets pushed at me; I parried as well as I could.” Although stabbed twice, Olney reached the redoubt and kept his company in good order before being carried away with the wounded.

It took a mere10 minutes for Redoubt 10 to fall into Continental hands. Doctor James Thacher, a surgeon with the Continental Army, wrote, “I was desired to visit the wounded in the fort, even before the balls had ceased whistling about my ears, and saw a sergeant and eight men dead in the ditch.” Nine Americans were killed and 30 wounded. The British had sustained eight casualties.

Baron Ludwig von Closen, a captain and aide to Rochambeau who helped take Redoubt 9, noted in his journal: “We established quarters during the night in these captured redoubts…. We completed the parallel and its communications and marked out a battery in front of it, between the two captured redoubts.” By morning, the second parallel had been completed. Troops added artillery to the redoubts, dug a trench connecting them, filled the entrances the British had created, and opened new entrances in the back.

Cornwallis could read the handwriting on the wall. He wrote to Clinton that “experience has shown that our fresh earthen works do not resist their powerful artillery. The safety of the place is, therefore, so precarious, that I cannot recommend that the fleet and army should run great risk in endeavoring to save us.” Washington, for his part, was extremely proud of his soldiers. He wrote that the redoubts “were attacked by storm” and that Rochambeau should honor his soldiers for “their gallantry in storming the enemy’s redoubt on the night of the 14th. instant, when officers and men so universally vied with each other in the exercise of every soldierly virtue.”

In the early hours of October 16, the British made a futile sortie to disable Allied artillery. That evening, Cornwallis tried to send men to safety across the river to Gloucester Point, but a storm thwarted the mission. In a sense, they “were attacked by storm” again. The Allies continued to shell the British lines. One observer wrote, “By the force of the enemy’s cannonade, the British works were tumbling into ruin.”

The Allies fired until a drummer, and then an officer bearing a white handkerchief, appeared on a parapet in late morning. Denny recorded: “Had we not seen the drummer in his red coat when he first mounted, he might have beat away till doomsday. The constant firing was too much for the sound of a single drum; but when the firing ceased, I thought I never heard a drum equal to it—the most delightful music to us all.” That drum beat and small fragment of cloth ultimately signaled the end of the ordeal that would make America a nation.

Surrender negotiations started that same day. Two days later, on October 19, Lt. Col. John Laurens, an aide to Washington, wrote “that the generals of the Allied Army will be at the Redoubt on the right of our second parallel at 9 o clock—this morning—when they expect to receive Lord Cornwallis’s definitive answer and sign the capitulation.” Based on the description, Laurens was likely referring to Redoubt 10. After signing the surrender documents, Cornwallis sent them to Washington, probably waiting in Redoubt 10. Washington noted, for the sake of posterity: “Done in the trenches before York Town in Virginia, Oct. 19 1781” and underneath signed “G. Washington.” Rochambeau and a French naval officer signed after him.

Cornwallis himself did not appear at the surrender ceremony that afternoon, claiming conveniently to be ill. Washington could not have cared less. The humiliated Cornwallis’s aide, Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara, took his place. The British marched between a mile-long line of American and French soldiers lining Hampton Road outside Yorktown and gave up their arms. Soldiers were taken prisoner, but officers were allowed parole if they promised not to participate in the war until exchanged. O’Hara, either through an honest mistake or a pompous desire not to recognize the new American ascendancy, tried to surrender his sword to French General Rochambeau, who wordlessly pointed to Washington. The American commander, in turn, refused to accept the surrender from an inferior officer and had O’Hara hand over his sword to General Lincoln. With that seriocomic pantomime, the surrender of Yorktown was complete.

In the days following the surrender, Allied soldiers began leveling some of the earthworks. If new British troops arrived, Washington did not want them using the works. Unknown to the Allies, Cornwallis’s desired reinforcements had left New York on the same day as the surrender. They arrived off the Virginia coast on October 24, but after learning of the surrender they quietly returned to New York a few days later.

Although Yorktown was the last major confrontation of the Revolutionary War, the struggle would not be over until September 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was signed. Key to the defeat of the British was the victory at Yorktown, and critical to the American victory at Yorktown were Redoubts 9 and 10. From their creation to their capture, the small fortresses of British defense were transformed into shining icons of American freedom.

Join The Conversation

Comments