By Charles W. Sasser

Unlike bomber crews that went home if they survived a designated number of missions, World War II fighter pilots like Lieutenant Jim Carl, 354th Fighter Group, United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), flew until the war ended, they got shot down over enemy territory and were captured, or they died.

“If you get through five missions,” Major “Pinky” O’Connor, one of three squadron leaders of the 354th, bluntly told replacements, “you will probably get smart enough to survive.”

America’s premier aircraft when the United States entered World War II were the heavily armed Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, nicknamed “The Jug” because of its bulk, and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Due to their limited range, however, neither was able to provide long-distance cover for bombers on missions into Nazi territory over occupied Europe, which left the bombers unprotected and vulnerable. The appearance of the North American P-51 Mustang, considered the best all-around fighter plane of World War II, changed the character of the Allied air war.

Its development was due not to the Americans, but instead to the British. A U.S. airplane manufacturer built it to British specifications in 1941, prior to the United States entering the fight. The early model lacked power at higher altitudes, but the 1942 version fitted with a Rolls Royce Merlin engine attained a top speed of 440 miles per hour, an altitude capacity ceiling of 30,000 feet, and an extended range that enabled it to provide fighter protection all the way from England to Poland and back, a round trip of 1,700 miles. It could outrun, outclimb, and outdive any fighter fielded by the enemy.

“When I saw Mustangs over Berlin,” Reichmarschall Herman Göring, commander of the German Luftwaffe, is said to have commented, “I knew the jig was up.”

The 354th Fighter Group, flying P-51 Mustangs and composed of three squadrons—354th, 355th, and 356th—deployed to Kent, England, in 1943 to fly escort for Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators on long-run bombings into Nazi territory. During its short tenure in Kent, the 354th shot down 68 enemy planes and lost 23 of its own.

“Your job,” the commanding general of the USAAF told the new unit, “is to achieve air superiority.”

Allied tactical air forces pounded the Luftwaffe relentlessly in the air and on the ground during the months prior to the Normandy D-Day invasion in order to achieve that superiority. Massive wide-ranging air assaults knocked out roads and rail lines, bridges, enemy convoys, troop movements, artillery emplacements, armor, and other targets of opportunity.

The first large-scale American bombing raid deep into the Reich with fighter protection all the way took place on January 11, 1944. Targets for the strike force of 663 B-17s and B-24s were Luftwaffe airplane and parts factories in Oschersleben, Halberstadt, and Brunswick. Fighter support consisted of 11 groups of P-47s, two groups of P-38s, and a single group of 49 P-51 Mustangs. The short-range American fighters had to turn back, but the Mustangs proved more than a match for the Luftwaffe interceptors, destroying a number of enemy fighters while suffering no losses of their own.

Two weeks after D-Day in June 1944, the 354th Group moved into France to support the Allied advance and take on Göring’s Luftwaffe. Lieutenant Jim Carl, a lanky native of Quapaw, Oklahoma, and fresh out of flight training on the P-51, linked up with the group a month later and was assigned to the 356th “Red Ass Squadron.” Squadron leader Major “Pinky” O’Connor had unintentionally coined the nickname after a long flight when he climbed out of his Mustang rubbing his butt and groaning, “Aiieee! Is my ass ever red!”

The squadron’s official emblem became a cartoonish red donkey wearing a broad grin.

Like most new pilots thrown into the mix, Carl had to learn his craft quickly. He began to count off the missions until he reached the magic number of five.

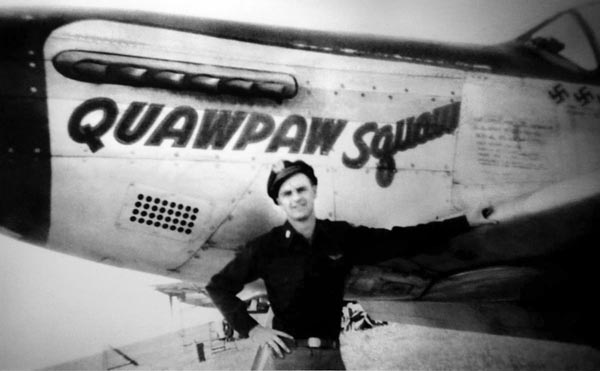

His first mission turned out to be anticlimactic. At the controls of Quapaw Squaw, named after his hometown, he flew wingman to “Pop” Young on a bomber escort. At 24, Pop was one of the older flyers. Carl was 21.

En route, the raiders flew over lines of grooves marking the World War I trenches that scarred the French countryside. Lieutenant Carl stared in disbelief, his thoughts briefly on all the men who had died in those trenches—and now the Americans were back again.

Over the target, an enemy airfield, the clear sky exploded with flak and antiaircraft fire. It seemed a miracle that a single airplane might make it through unscathed. Carl was reckoning himself a goner—and on his first mission at that—when Pop Young reported engine trouble. As his wingman, Carl turned back with Pop to escort him to base.

Four missions to go.

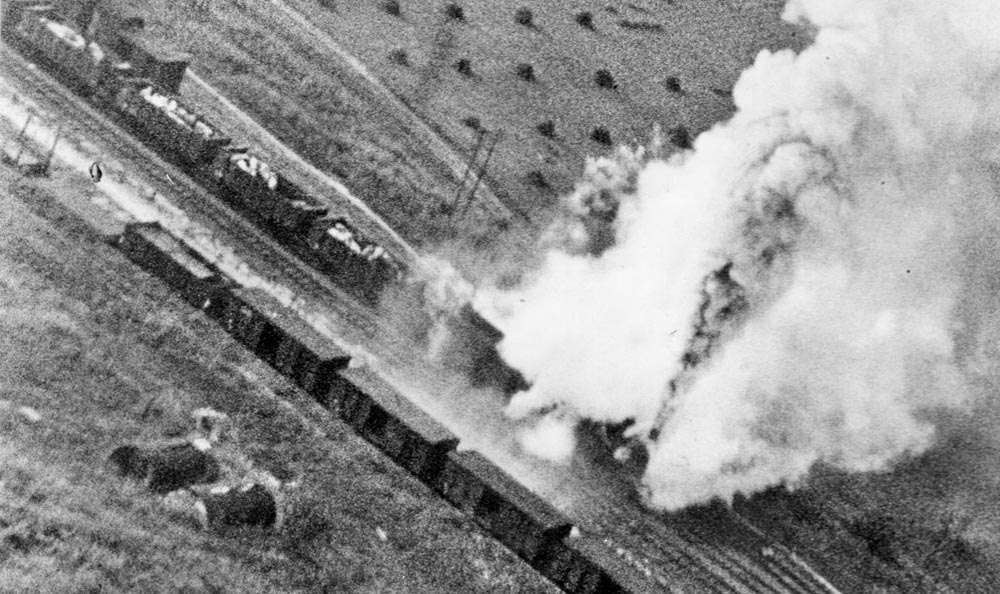

Lieutenant Carl’s second mission involved an air-to-ground attack on a freight train loaded with fresh troops and supplies steaming across a wide plain toward the German front. Armed with quad .50-caliber machine guns and two 250- or 500-pound bombs mounted on wing racks, the P-51 excelled in ground attack and support as well as in air combat.

In a long line, the Mustangs made runs on the train at more than 400 miles per hour while German troops in green and gray uniforms on flatcars unlimbered their cannons and machine guns on the attacking fighters.

Carl rolled Quapaw Squawdirectly at the approaching locomotive and strafed the train all the way to its caboose. Tracers from German machine guns flashed through the formation like meteors. A train wheel blasted into the air and whizzed past Carl’s cockpit.

He flew so low that he caught expressions on the faces of flatbed antiaircraft crews before they and their cars were reduced to kindling, blood, and bone chips. On his climb out, he glanced back over his shoulder and saw the train derailed, cars overturned and smoldering, surviving troops running for the hills.

Three to go.

He acquitted himself well in air-to-air encounters and acquired a reputation for being cool and deadly under fire. During one dogfight, the 354th Group with 38 Mustangs engaged a superior force of 51 German Messerschmitt Me-109s and Me-110s. Buzzing like giant bees at 20,000 feet, planes of both teams mixed it up in a furious maelstrom of violence, ducking and darting and sweeping, muzzles flashing and flaming. A gnat against a distant cloud one moment quickly became a flying dragon spitting fire the next. There was no time for thinking at such speeds, only action.

Outflown and outgunned, the Germans broke off contact and fled with their figurative tails between their figurative legs. Quapaw Squawsurvived with only a few holes in her fuselage. Lieutenant Carl was still in the fight.

A few days later, about 40 planes from the 354th flew at 10,000 feet approaching an enemy ground installation when someone radioed an alarm: “Bogeys!” German Messerschmitts swarmed out of the clouds like frenzied hornets.

“Break left! Now!” Group leader Major Carl Depner ordered.

The formation broke in a single unit, jettisoning its bombs to lighten the planes for aerial combat. Mustangs climbed in waves and burst through the bogeys with guns blazing. Lieutenant Carl swept onto an enemy aircraft’s backside and laid on his trigger, anticipating a kill.

His guns malfunctioned. He found himself defenseless and surrounded by vampires. His only recourse was to fly like hell in the middle of swarming airplanes all shooting at each other. Fighters, both enemy and friendly, exploded in bright balls of fire or streaked toward earth trailing smoke and flame.

Major Depner’s wingman, Boze, was shot down and killed. Moments later, Depner got hit. He pulled out of the fight and headed for home. Fire in the cockpit forced him to parachute out. That was the last anyone heard of him.

Those were the only American planes lost in the dustup, while the Germans lost nearly two dozen blasted out of the sky. And Carl had not fired a single shot.

This was Quapaw Squaw’s magic mission of five. Carl was beginning to think he might make it after all.

The Red Asses’ squadron leader, Major O’Connor, ballsy and cavalier, took care of his men and thereby commanded a great deal of respect. During a raid on a heavily defended German airfield, Carl sprayed a .50-caliber swath of destruction into enemy fighters caught by surprise on the ground. He pulled out of his run and circled at 1,000 feet. Several shattered Messerschmitts spewed flame and smoke into the air. A fire truck at the end of the asphalt runway near some concrete revetments had overturned and burst into flames. Tracers zipped up from hardened antiaircraft sites.

Major O’Connor was on the radio calling off the attack when Carl noticed an undamaged Me-109 partly concealed underneath a tree off to one end of the landing strip.

“Hallum Two,” he radioed Pinky. “I’m making another run on the bogey hiding underneath the tree.”

“Roger, Squaw Man.”

Carl dipped a wing into a belly-wrenching dive almost straight down at the parked aircraft. He felt the smooth stutter of his .50-caliber machine guns throughout his body as he gnawed up turf, the tree, and the Me-109. He zoomed through the black and red ball of gasoline flame he had ignited and pulled up in a wild, weaving flight through streams of tracers attempting to bring him down.

Typically, Major O’Conner never left one of his fighters alone in a fight. While Carl was taking care of the hidden Me-109, O’Connor was raising hell at the opposite end of the airfield, creating a diversion. When the squadron returned to base near Cherbourg, Pinky had almost as many holes in his Mustang as Carl had drilled through the parked Me-109.

“What the hell were you thinking?” Carl scolded him. “You didn’t have to make another run.”

“I did it to give you a chance,” the major replied with a shrug.

Shortly after that, Major O’Connor was shot down during a long escort of B-17s. He parachuted out directly on top of an SS gun crew.

Other pilots got shot down more than once and lived to tell about it. Captain James Edwards, a big, tall boy and winner of two Distinguished Flying Crosses, was busted out of the air twice and wrecked two other airplanes while trying to bring them home riddled by gunfire.

“You keep losing planes,” Carl admonished him, “and they’ll make you start paying for them.”

Even Quapaw Squawwas shot down on what was to be a routine sortie. Since that particular mission expected little or no contact, Carl allowed a rookie named Homberg to fly the Squaw.A battery of German 88s on the ground brought her down like a meteor. That was Homberg’s first and last mission.

Carl named his replacement Mustang Quapaw Squaw II.

Most fighter pilots developed a grudging respect, even admiration, for pilots of the opposite uniform. Shooting each other down was nothing personal. It was not about killing a man; it was about killing a machine.

In supporting the Allied advance after D-Day, the 354th basically followed General George Patton’s Third Army across France, into Belgium and the Battle of the Bulge, then across the Siegfried Line into Germany. Lieutenant Carl was up to 60 or so missions in his logbook, and the Red Asses were sweeping out ahead of Patton when he encountered an Me-109 jock in a one-on-one dogfight that could end only one way—with the destruction of one or the other.

Although the savage-looking Me-109s were not quite on par with the mosquito-like P-51s, they could be quite formidable when flown by a top-line pilot who knew his way around the sky. As a dozen or so Me-109s bounced the Mustangs out of the sun, Carl tacked onto an enemy plane that began twisting into maneuvers Carl would not have thought possible before now. The dogfight degenerated into a deadly game of tic-tac-toe played at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour.

Carl seized the first advantage by grabbing onto the guy’s exhaust and zig-zagging with him through the air, sending tracers slashing after him. The Me-109 seemed to dive every time just before the bullets reached him.

The German suddenly switched positions with Carl in a maneuver so skillfully executed that it left Carl breathless with astonishment. The Me-109 was now on the American’s ass.

Carl feinted, bobbed, and weaved across the sky, trying to shake the Me-109 before tracers flashing past his cockpit caught him. The guy might fly like a superhero, but, fortunately, he could not shoot for crap. That was the only thing that saved the American.

The two fighter planes dueled it out for what must have seemed an eternity to the combatants. First one took the advantage, then the other, each unable to administer a fatal blow.

They broke apart and circled warily at a distance, each striving to fight out of the sun while forcing the other to fight into it.

They charged like gladiators, weapons blazing. Lead spanged into Quapaw II’s fuselage. The fighters passed wing tip to wing tip at a combined speed of more than 800 miles per hour. Carl glimpsed his rival’s face—young and encased in a brown aviator’s cap, ear pieces loose, intense and concentrated—nothing like the gross caricatures on the “Know Your Enemy” propaganda posters.

Carl pulled into a turn so sharp he thought his wings were ripping off. That put him back on the hotshot’s tail. The German dived with Carl in pursuit, his aircraft vibrating at speeds beyond its red line. The earth below rushed at him.

The first one to “chicken out” would find himself at a crucial disadvantage, as it would permit the other a tail position in good machine-gun shape at a relatively slow recovery speed. The German bobbed and weaseled, making himself a difficult target and apparently determined to bury them both in the ground rather than pull out of his dive.

Carl glimpsed trees and fences coming at him. A farmhouse. Some geese flying.

At the last instant, just when it appeared both planes would crash, the German “chickened out” and leveled off just above the tree line. Evasion lay in his climbing to a more favorable level for maneuvering, which meant giving up precious speed and making himself vulnerable to his pursuer.

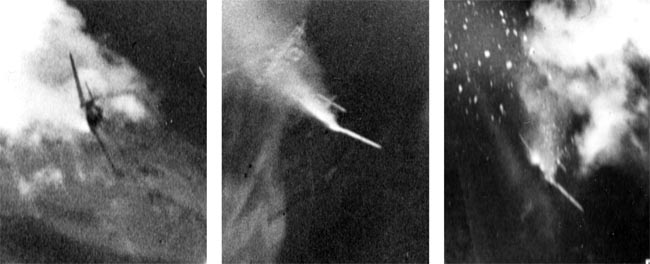

Tree branches quaked and bowed from the combined speed of the two fighters’ slipstreams. Carl anticipated his foe’s next move and caught the Me-109 in his sights as it pulled up and out. He squirted it with his quad-50s, tumbling it through the low air like a pheasant shotgunner in flight. It burst into bright flames as it struck the ground. Burning parts of it exploded in all directions. No pilot could have lived through such a conflagration.

Momentary sadness and guilt overcame Lieutenant Carl as he pulled back on Squaw II’s throttle and circled the field, wagging his wings in tribute. He thought he might have liked to have congratulated the German over a cup of coffee on a duel well fought.

P-51 Mustangs flew 213,873 sorties during the war, losing 2,520 planes to all causes, including enemy action. In turn, Mustangs shot down 4,950 enemy aircraft, a feat second only to the carrier-borne Grumman F-6F Hellcat used in the Pacific War.

The three squadrons of the 354th Fighter Group in Europe destroyed more enemy aircraft in aerial combat, 701, than any other while losing only 63 of their own pilots.

Jim Carl flew 86 combat missions with the Red Ass Squadron, won two Distinguished Flying Crosses, and left the USAAF as a lieutenant colonel. He lost a lot of friends during the final year of the war.

Charles Sasser is the author of the classic book of sniper warfare titled One Shot-One Kill. He has written dozens of other books and articles and appeared on numerous television networks including ABC, Fox, the History Channel, and CNN. He is a veteran of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Special Forces. He resides in Chouteau, Oklahoma.