By Charles Whiting

Adolf Hitler believed in Vorsehung (providence). The German leader felt that if anything was going to happen to him, such as assassination, there was nothing he could do about it. He had been selected by fate to achieve something great; he would not die, either by accident or assassination, until he had fulfilled that God-given mission.Time and time again in the past, providence, not planning, had taken care of him. In 1933, for instance, just before he became master of the Third Reich, he was involved in a terrible car crash with a truck. He emerged from the wreckage stating that he could not die yet—his mission had not yet been achieved.

It was the same with assassination attempts. Hitler explained that he had many enemies and expected disgruntled Germans and others to try to kill him. But they would never succeed, especially if they came from the German working class. He used to state to his staff quite categorically, “Mil tut kein deutscher Arbeiter was” (“No German worker will ever do anything to me.”). Once, when he was advised by worried police to use the back entrance to a noisy and angry meeting of workers, Hitler snorted, “I am not going through any back door to meet my workers!”

As for those aristocratic Monokelfritzen (Monocle Fritzes, those high-born, monocled aristocrats Hitler had hated with a passion ever since the Great War), both civilian and military, whom he knew from his intelligence sources had been trying to eradicate him in these last years of the 1930s, he was confident that this personal providence would save him. And in truth, until the very end, providence did protect Hitler from all the attempts on his life, including the generals’ plot to kill him in July 1944.

Naturally, ever since Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933, his security guards had taken secret precautions to protect him. Like some medieval potentate, all the Führer’s food was checked daily before it was served to him. Each day, his personal doctor had to report that the Führer’s food supplies were free of poison. Party Secretary Martin Bormann ran daily checks on the water at any place where the Führer might stay to ascertain whether it might contain any toxic substances.

Later, when Bormann, in his usual fawning manner, started to grow “bio-vegetables” in his Berchtesgaden gardens for the Führer’s consumption, Hitler’s staff would not allow the produce to appear on the master’s vegetarian menu. Once, just before the war, a bouquet of roses was thrown into the Führer’s open Mercedes. One of his SS adjutants picked it up and a day later started to show the symptoms of poisoning. The roses were examined and found to be impregnated with a poison that could be absorbed through the skin. Thereafter, the order was given out secretly that no “admirer” should be allowed to throw flowers into Hitler’s car. In addition, from then on, adjutants would wear gloves.

“We Have not Reached the Stage in Our Diplomacy When We Have to Use Assassination as a Substitute for Diplomacy.”

On another occasion, Hitler, who loved dogs (some said more than human beings), was given a puppy by a supposed admirer. It turned out that the cuddly little dog had been deliberately infected with rabies. Fortunately for Hitler, and not so fortunately for the rest of humanity, the puppy bit a servant before it bit him. It seemed that Hitler’s vaunted providence had taken care of him yet again.

Thereafter, plan after plan was drawn up to kill Hitler by his German and Anglo-American enemies. All failed. Although back in 1939, the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, had stated, “We have not reached the stage in our diplomacy when we have to use assassination as a substitute for diplomacy.” Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided in April 1945, however, that Hitler must die—by assassination! He gave the task to his most ruthless and anti-German commander, Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, the head of Royal Air Force Bomber Command, whose aircrews often called him bitterly “Butcher” Harris.

Back in the summer of 1943, Harris had sworn that Berlin would be “hammered until the heart of Nazi Germany would cease to exist.” Hard man that he was, Harris had once been stopped by a young policeman and told if he continued to speed in his big American car, he would kill someone. Coldly, “Bomber” had replied, “Young man, I kill hundreds every night.” He now ordered that Hitler should be dealt with at last in his own home. The Führer had escaped, so Allied intelligence reasoned, from his ruined capital Berlin. So where could he be? The answer was obvious. “Wolf,” the alias Hitler had used before he achieved power in 1933, had returned to his mountain lair.

In that last week of April 1945, Allied intelligence felt there were only two possible places where Hitler might now be holed up since his East Prussian headquarters had been overrun by the Red Army. Either he was in Berlin, or at his Eagle’s Nest in the Bavarian Alps above the township of Berchtesgaden. Reports coming from Switzerland and relayed to Washington and London by Allen Dulles of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) stated that the Germans were building up a kind of last-ditch mountain fortress in the Austrian-German Alps, so Allied intelligence was inclined to think that Hitler had already headed for Berchtesgaden where he could lead the Nazis’ fight to the finish. The bulk of the Reichsbank’s gold bullion had already been sent to the area to disappear in perhaps the biggest robbery in history.

Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring had gone in the same direction, followed by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, who had taken up residence in his stolen Austrian castle. More importantly, SS General Sepp Dietrich’s beaten 6th SS Panzer Army was retreating from Hungary, followed by the Red Army, heading for Austria and the same general area. Thus, the Allied planners decided that if they were finally going to assassinate Hitler, they would find him in his mountain home—built for him over the last decade by Bormann. Prominent Nazis, the Prominenz, just like Mafia chieftains, had erected their own homes in Berchtesgaden to be close to Hitler.

Once it had simply been a rural beauty spot, with a couple of modest hotels surrounded by small hill farms that had been in the same hands for centuries. Bormann changed all that. He bribed, threatened, and blackmailed the Erbbaueren (the hereditary farmers, as they were called) to abandon their farms. He sold their land at premium rates to fellow Nazis and then, as war loomed, erected a military complex to protect the Führer whenever he was in residence on the mountain among the “Mountain People,” as the Nazis called themselves. After he completed his 50th birthday present for the Führer, the Eagle’s Nest, which Hitler visited only five times and which cost 30 million marks to construct, Bormann turned his attention to making the whole mountain complex as secure as possible, both from the land and the air.

Bormann, the “Brown Eminence” as he was known, the secretive party secretary, who in reality wielded more power on the German home front than Hitler himself, declared the whole mountain sperrgebiet (off limits). A battalion of the Waffen SS was stationed there permanently. Together with mountain troops from nearby Bad Reichenhall, the SS patrolled the boundaries of this prohibited area 24 hours a day, something the British planners of Operation Foxley, a land attack planned by the British in February 1945, had not reckoned with.

If Anyone Could, Harris Swore, He Would Blast Berchtesgaden Off the Map.

Then, Bormann turned his attention to the threat of an air attack. Great air raid shelters were dug, not only for the Führer and the Prominenz, but also for the guards, servants, and foreign workers—there was even a cinema, which could hold 8,000 people. Chemical companies were brought in and stationed at strategic points on the mountain. As soon as the first warning of an enemy air attack was given, they could produce a smoke screen, which, in theory, could cover the key parts of the area in a matter of minutes. Finally, there were the fighter bases such as Furstenfeldbruck in the Munich area where planes could be scrambled to ward off any aerial attack from the west or indeed over the Alps from the newer Allied air bases in Italy.

Whether it was because of Bormann’s precautions, the problem of flying over the Alps in a heavy, bomb-laden aircraft, or Allied scruples about bombing an enemy politician’s home, the mountain had not been seriously troubled by air raids until now. Bomber Harris was determined to end all that. If anyone could, Harris swore, he would blast Berchtesgaden off the map.

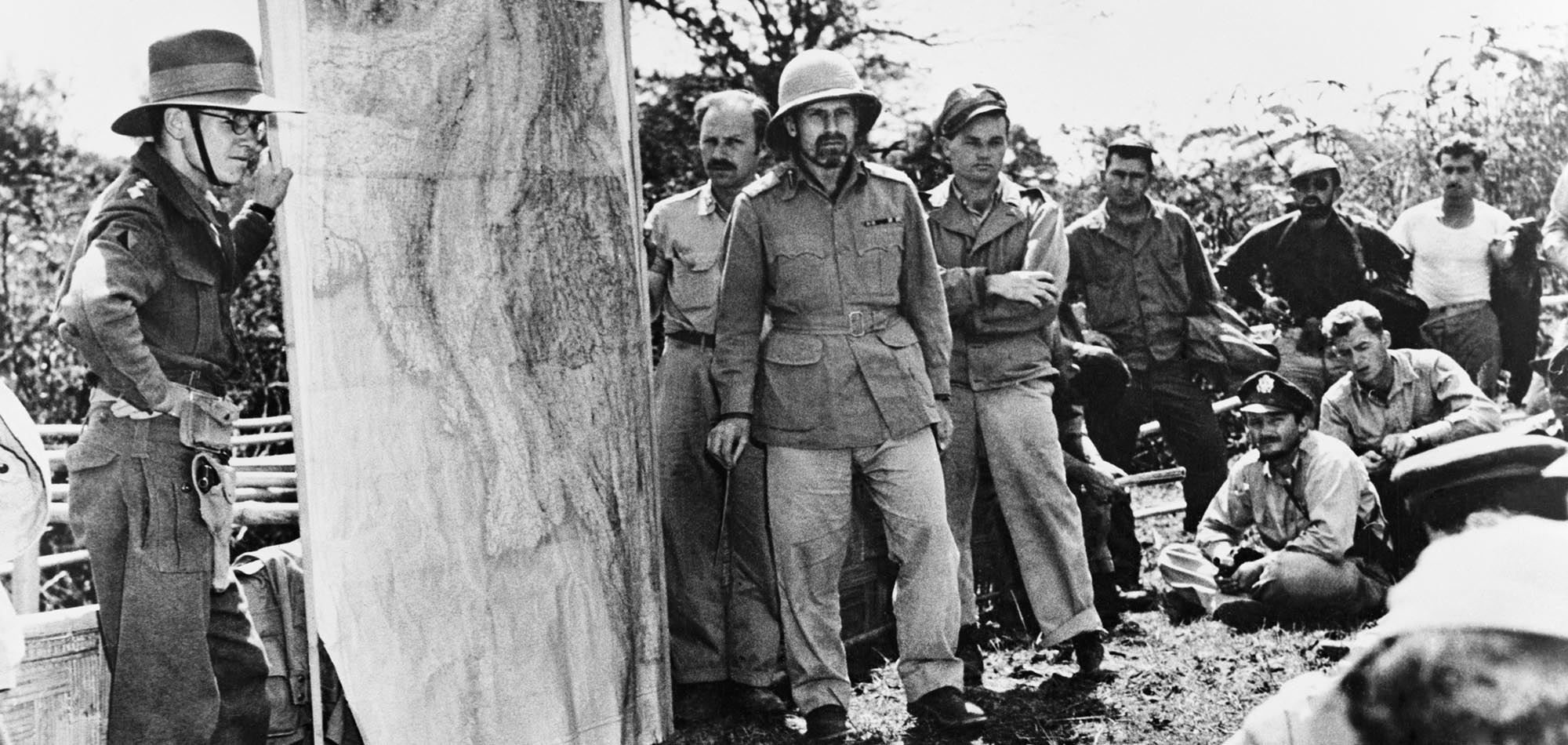

To do so, he picked one of his most experienced bomber commanders: 24-year-old Wing Commander Basil Templeman-Rooke, who had begun his bomber career in 1943. By the end of that year, he had already been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and more importantly had flown over the Alps to bomb Turin in the hope that a bombing raid on that city, so far away from England, would encourage the Italians to surrender. After one tour of duty, Templeman-Rooke commenced another one in May 1944. He took part in the D-Day preinvasion bombing of French railways, storage depots, and other targets, and then in the attacks on V-1 buzz bomb sites after the invasion.

The controversial bombing of Dresden followed in February 1945. Shortly thereafter, Templemann-Rooke had been given the command of the Royal Air Force’s 170 Squadron and awarded a Bar to his DFC. In March, he received the Distinguished Service Order. For Harris, the young squadron commander must have seemed the ideal leader for what he had in mind for 170 Squadron. He was young, brave, very experienced and, above all, lucky. In his two years of combat, he had survived over 40 missions, and even when he had been hit by flak over Gelsenkirchen, he had brought his Avro Lancaster bomber back on two engines and crash-landed the four-engine plane without injury. Now, Harris ordered Templeman-Rooke to fly his squadron’s last combat mission of the war, its target perhaps the most important one left in Germany during April 1945.

For days now, although the hilltops were still covered with snow down to 900 meters and causing fog, reconnaissance planes kept flying over the mountain, setting off the wail of the sirens and sending the populace scurrying for the shelters. Then, once again the smoke screen would descend on the deserted homes of the Prominenz. For even Hitler’s most devoted followers had reasoned that the mountain was no place to be at this stage of the war. Still, there had as yet been no attempt to bomb the area.

That changed at 0930 on Wednesday, April 25, 1945. On the half hour precisely, the pre-alarm sirens started to sound. Obediently, the locals began to file into their air raid shelters, believing that, as usual, nothing much would happen. This time they were wrong. Most of the mountain, right up to the Eagle’s Nest at 9,300 feet, was obscured by fog. This time, on Harris’s order, 170 Squadron, part of a force of 318 Lancasters, was determined to carry out its mission. Within half an hour of the pre-alarm being sounded, the first bombs were raining down on the twin heights of Klaus-and-Buchenhoehe.

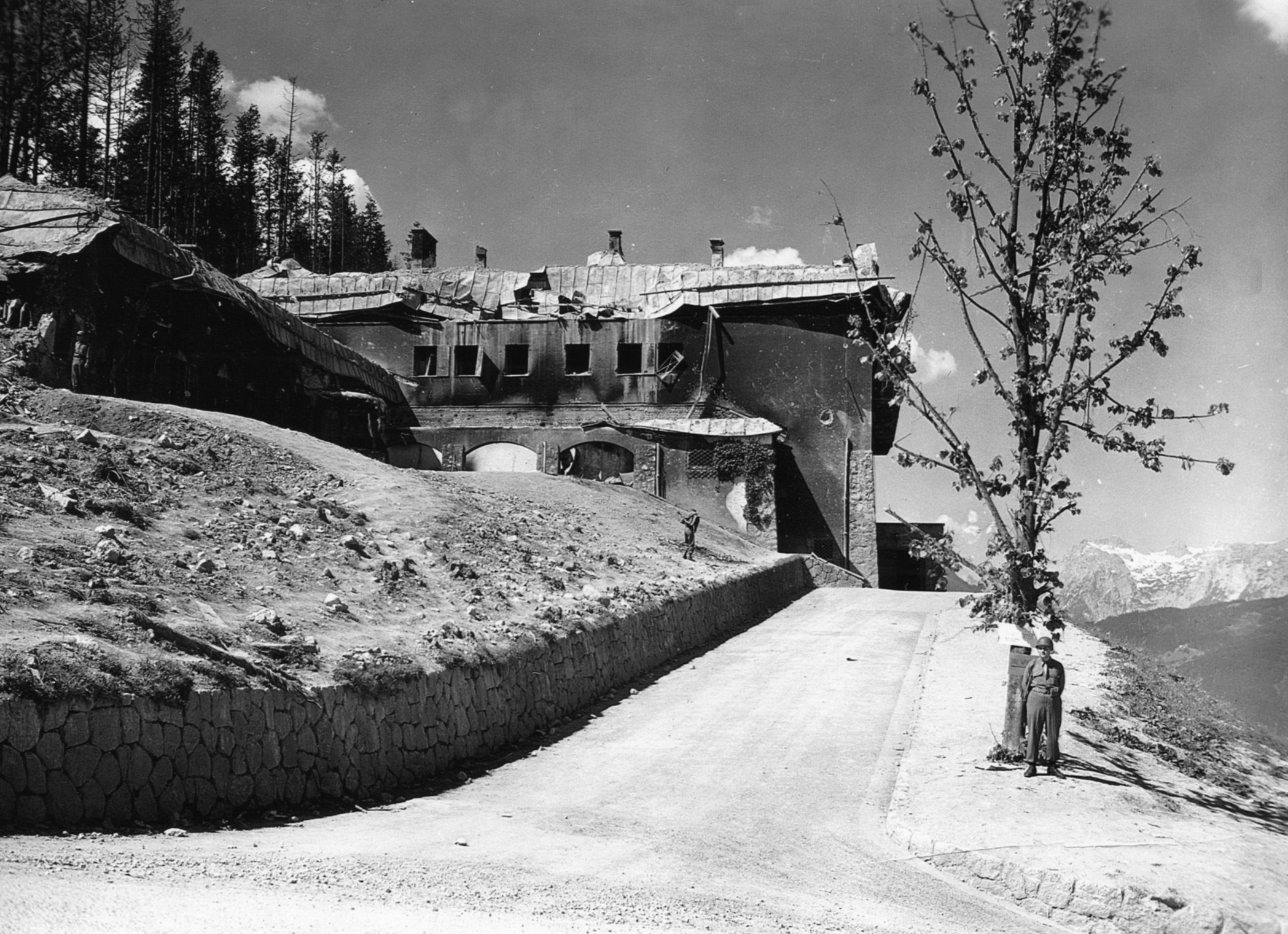

Then came the second raid. According to German reports, the Lancasters swept in shortly afterward, dropping 500-pound bombs. Immediately, they hit Hitler’s Berghof, where back in what now seemed another age, the Führer had once received British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, the “Umbrella Man,” as the Germans had mocked him due to his appearance. Afterward, as German eyewitnesses recorded, the interior looked like a landscape after an earthquake. Göring’s house, demolished together with his swimming pool, followed. Bormann’s house received a direct hit. The only place that was not destroyed or damaged was the Eagle’s Nest. It had been well camouflaged with tin leaves and was perhaps too small a target for Harris’s men. But as the bombers swept on to attack nearby Bad Reichenhall, where 200 people were killed that day, they left behind them only smoking wreckage, which would be added to when the SS guards retreated, setting fire to everything they could not loot.

But the RAF’s raid on the mountain had been in vain. Templeman-Rooke had been misinformed—the Führer was not in residence. He had remained in his bunker, spared yet again by the “providence” in which he believed so strongly. But he knew he could not go on forever. As he declared to anyone still prepared to listen to him in his Berlin bunker, he was not going to die at “the hands of the mob” like his friend and fellow dictator Mussolini. Nor was he going to allow himself to be “paraded through the streets of Moscow” in a cage. So, a broken man, embittered at the failings of his own people, and perhaps a little mad, the leader who had survived so many assassination attempts died by his own hand. His “providence” had run out at last.

Even today, at a certain angle, one can see the series of depressions leading up to where Göring’s house was, marking one bomber’s run into the attack. Of the house itself only a few steps remain next to some bushes where visitors allow their dogs to do their business—“Hundepissecke” the locals call it. One wonders what roly-poly Göring would have said. Probably, he would have reached for his shotgun and started blazing away; he was always very keen to shoot anything on four legs.

Well-known author Charles Whiting contributed regularly to WWII History. He also wrote a number of well-received books, which have sold millions of copies worldwide.

I believe that an RAF officer by the name of James Bowie Miller was present at this RAF raid and possibly was awarded a DFC as a result of it. Can anyone help me to confirm this?

Hello Margaret,

Yes, MILLER was certainly on the raid in MULLINS’ crew. I can tell you much more but am interested in what happened to MILLER post WWII, until his retirement in 1961.

Cheers,

Neil

(Lt Col Neil C SMITH, AM Retd).

[email protected]

0411143041

Melbourne, Victoria.

“ever since Hitler’s election as chancellor in 1933” Hmmm, I thought he was APPOINTED, not elected. Makes one wonder what other inaccuracies this piece may contain.

You are correct. Hitler lost the German multi-party presidential election to 84 year old Paul von Hindenburg in a runoff held April 10, 1932. In the July 1932 Reichstag (German parliament) elections, the Nazi Party became the largest of the parties but failed to reach a majority.

Another Reichstag election was held in November, where the Nazis remained by far the largest of the parties, retaining a third of the seats. Two months later, Hindenburg appointed Hitler, political leader of the largest of the political parties, chancellor. Upon Hindenburg’s death the following year, Hitler assumed total power as Führer.

Thanks Charles, Well written, easy to follow, and interesting. I knew much of it, but that’s always the point; you can’t know it all.