By Angus Scully

By February 1945, the green Allied formations that landed on D-Day had become hard professional armies. Army, corps, and division commands had been shaken down and were operating efficiently. The supply problem that had plagued operations in the autumn had been solved. But most crucial for winning on the battlefield against the still formidable Germans were the officers and NCOs of the front-line infantry battalions. Those who had survived the previous eight months of combat had gained invaluable experience.

When Allied offensive operations resumed after the Battle of the Bulge, the German armies were fighting for their lives on their own soil. They were still very dangerous, but the seasoned officers and NCOs leading Allied battalions into action were their match by 1945. The fascinating story of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada shows the impact on the battlefield of experienced infantry leaders—young civilians from a variety of backgrounds who became such effective leaders.

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada has a distinguished history, tracing its origin back to 1861. The Queen’s Own prides itself on the traditions of rifle regiments. Riflemen are expected to act with initiative, speed, and resolve, and always to support one another. Having been a D-Day assault battalion, the Queen’s Own was, by 1945, a hard-fighting and close-knit outfit. The regiment fought through Normandy, helped close the Falaise Gap, took part in the siege of Boulogne, and became “water rats” in the flood and mud battles of the Scheldt. The men of the battalion had been green when they ran across the beaches on D-Day morning, but in February 1945, they were professional warriors.

While the Battle of the Bulge was still raging, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, and his staff had no intention of waiting for spring to renew their offensives. On December 31, 1944, Ike said that once the Ardennes salient was reduced it was his intention “to destroy enemy forces west of the Rhine, north of the Moselle and to prepare for crossing the Rhine.” The task was given to Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, which planned a pincer movement.

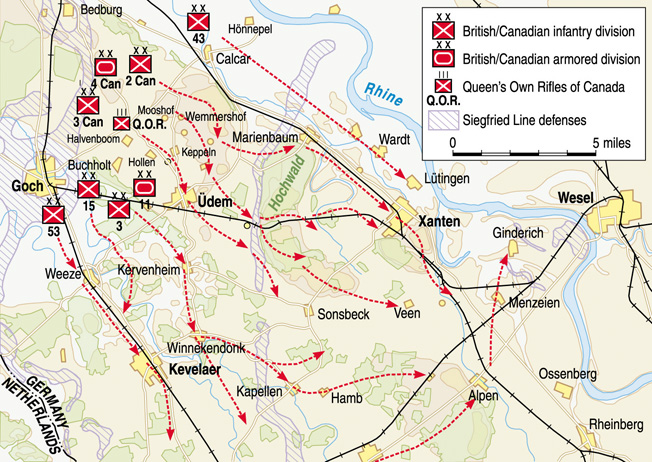

In Operations Veritable and Blockbuster, the First Canadian Army would attack south from the Nijmegen salient. The Ninth U.S. Army was transferred to 21st Army Group and would, in Operation Grenade, attack north. Eisenhower met with General Omar Bradley, commander of 12th Army Group, on January 30 and, the Germans having been defeated in the Bulge, shut down operations there and moved the weight of Allied operations to the north. Veritable was scheduled for February 7 and Grenade for February 9, 1945. There was a great deal of controversy at the highest levels of the Allied command over strategy and operational structures, but however much that may entertain historians today, the reality for the men on the ground was to prepare to fight the Germans on their own soil.

The First Canadian Army had begun planning for the Rhineland campaign on December 7, 1944, with a target date of January 1, 1945. Montgomery had transferred the British XXX Corps to the First Canadian Army for the attack. The Germans had other ideas, and their Ardennes offensive of December 16 caused Montgomery to remove XXX Corps from Canadian command on December 19 and to shut down planning for Veritable. First Canadian Army spent the ensuing month on high alert in case of an enemy attack on the Nijmegen salient.

On January 16, active planning for Veritable resumed. The XXX Corps was returned to Canadian command on January 18, and the start date was set for February 8. The cost to the Germans of the failed Ardennes offensive was high, not just because of the battlefield defeat, but also because the Allies had to delay the clearing of the west bank of the Rhine by only five weeks. Allied success in Veritable and Grenade would doom the Germans in the west.

For Veritable, General Harry Crerar’s First Canadian Army would have XXX British Corps and II Canadian Corps. Crerar was a capable but colorless commander who had had several major run-ins with Montgomery, as indeed did many non-British generals under Monty’s command. It was no accident on Montgomery’s part that Veritable would be carried out by two of his favorite corps commanders: Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks of XXX Corps and Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds of the II Canadian Corps. When Simonds was commander of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, he served under Monty in Sicily and Italy and became Monty’s protegé. Simonds then commanded the II Canadian Corps in the controversial closing of the Falaise Gap in Normandy, and had been in temporary command of the First Canadian Army while Crerar was ill, during the Battle of the Scheldt in October and November 1944. Simonds was known as a cold, ruthless, and innovative general who did not lead, but commanded.

The Total Ammunition Tonnage… Would be the Equivalent in Weight to the Bomb-Drop of 25,000 Medium Bombers.”

The administrative buildup by Crerar’s headquarters was immense. The enemy was expected to fight fanatically, defending their own country from the prepared positions of the Siegfried Line. The weather was cold and the ground was muddy—flooded in many areas— so the tanks would have to move on roads. Cities had been bombed to rubble, creating obstacles to the planned advance. Two forests, the Reichswald and the Hochwald, would be difficult to take from determined defenders. With 450,000 men under his command, Crerar used 50 companies of engineers, three road construction companies, and 29 pioneer companies to prepare roads and depots. Gasoline stores were built up to provide 153 operational miles for XXX Corps and 200 operational miles for II Canadian Corps.

Crerar said, “If the ammunition allotment for the operation, which consisted of 350 types, were stacked side by side and five feet high, it would line a road for 30 miles. The total ammunition tonnage … would be the equivalent in weight to the bomb-drop of 25,000 medium bombers.”

The opening artillery barrage on February 8 was the most concentrated of the war in the west. It lasted over five hours, and 1.5 million shells were fired on a seven-mile front by 1,034 guns. On this narrow front, XXX Corps attacked with the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions under command. A 30,000-yard smoke screen concealed the operation from German observation on the other side of the Rhine. The rest of II Canadian Corps was not brought into the line until February 15 when the front had opened out.

German defenses in the Rhineland consisted of the north end of the Siegfried Line, called the Schlieffen Line by the Germans. In front of the Hochwald there were lines of entrenchments, antitank ditches, and wire entanglements 600 to 1,000 yards apart. Villages had been converted into islands of resistance surrounded by wire and trenches. Buildings were strengthened with concrete. The area was manned by the First Parachute Army, which included the II Parachute Corps and the XLVII Panzer Corps. German resistance would be ferocious. Hitler had issued a no retreat order. It was to be a fight to the death for the Fatherland.

The Germans opened the banks of the Rhine to flood low-lying areas, limiting the ground on which the Canadian Army could operate. They also opened the Roer River dams in front of the U.S. Ninth Army, which had planned its attack (Operation Grenade) in the Rhineland for February 10. The flood stopped the Americans until February 23. The Germans were able to move their reserves, including two parachute and two panzer divisions, to meet the First Canadian Army. One German division had been facing XXX Corps on February 8; there were nine German divisions in action two weeks later.

By February 21, the First Canadian Army had advanced 20 miles over terrible terrain, but the enemy still maintained an unbroken front and the prepared defenses of the Hochwald section of the Siegfried Line. Crerar met with his corps and divisional commanders on February 21 and decided to shift the weight of his operations from XXX Corps to the II Canadian Corps. This second part of Veritable, called Blockbuster, was scheduled to launch on February 26.

That morning, two outstanding riflemen of the Queen’s Own, Platoon Sergeant Aubrey Cosens and his company commander, Major Ben Dunkelman, led an attack against German positions at Mooshof. It was an obscure hamlet, but it held the key to the advance of an entire Canadian corps.

The Queen’s Own had spent the previous three months in defensive lines on the Maas River, securing the Nijmegen Salient. This time had been used in training and integrating replacements to make up for the infantry shortages resulting from the ferocious fighting of the summer and autumn of 1944. The Third Canadian Infantry Division had sustained the highest number of casualties of any Allied division in the Normandy campaign. On the Maas, intensive patrolling kept the men sharp, and by February 9 morale was very high as the battalion took the Dutch town of Millingen on the left flank of Operation Veritable.

By February 23, orders for the next phase of action for the Queen’s Own Rifles were starting to arrive in detail. Simonds planned an all- out blow, first taking the ridge that ran from Calcar southwest to Udem with attacks by the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions. This would be followed by a breakout attack by the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the 11th British Armoured Division. The armored divisions were to take the Hochwald and exploit toward Xanten. Engineers would turn a rail line into a dry road for supplies, and the attack would be backed by heavy artillery support.

On February 24-25, Lt. Col. Steve Lett and his battalion officers made a reconnaissance of the proposed front. What they saw was daunting. They knew their opposition would be the German 6th and 8th Parachute Regiments in reinforced concrete positions in farmhouses and tiny villages across their front.

Cowling Knew it was Going to be a Different Affair From Their Previous Experience When he Saw Dunkelman Walking Around Waving His Pistol and Yelling, “Who’s ready for war?”

The Queen’s Own would have to attack over flat, open country overlooked by the enemy on the Udem-Calcar Ridge. Lett decided not to adhere to the standard procedure of following close behind the moving artillery barrage. He said, “Enemy artillery is not very flexible. His defensive fire is brought down very accurately. However, once the limitation of the area is determined, it can be circumvented with comparative safety.” Therefore, Lett delayed the assault by a half-hour. The plan to advance over open ground against German paratroopers had a sobering effect on the officers. Major Dick Medland of A Company told his officers, “This could be the toughest fight we’ve ever been in. A lot of us won’t make it.”

The Queen’s Own Rifles spent the night in their slit trenches in a cold rain. The men were called out at 3:30 am and fed sandwiches and coffee laced with rum. Cosens checked his men. Finding Private Don Chittenden struggling with his wet web equipment, he knelt in front of him to get the buckles done up. Chittenden felt as if he were being fussed over by an anxious mother, and when he looked down at Cosens they both laughed loudly. Private Don Cowling knew it was going to be a different affair from their previous experience when he saw Dunkelman walking around waving his pistol and yelling, “Who’s ready for war?”

At 4:30 am, the Queen’s Own started forward under the artificial moonlight created by antiaircraft searchlights reflecting off the overcast. Quite a few of the riflemen thought it helped the enemy more than it helped them. While Lett might have wanted to avoid the German artillery counterfire, the Canadians came under ferocious fire from automatic weapons and mortars. Company D suffered heavy casualties crossing the 500 yards of open ground, and only a few men from 16 Platoon made it up to the buildings.

Corporal E.W. Fraser was one of the few who did, and he called back for the others to speed things up just before he was cut down by a point-blank burst of Schmeisser fire from the window of the farmhouse. Dunkelman ordered his men to dig in away from the buildings, expecting a German counterattack and prearranged German bombardment of the farm, but 16 Platoon did not get away before the German fire started.

As Dunkelman later put it, “All hell had broken loose. The bodies of the dead, wounded, and dying lie everywhere you look. It’s a nightmare. The struggle for Mooshof hangs in the balance.” The rest of the story is best told by the eyewitnesses whose testimony was collected as part of the investigation into awarding Cosens a posthumous Victoria Cross.

“After our Platoon Commander, Lt. Lloyd McKay was wounded, Sgt. Cosens took over,” remembered Corporal H.F. Gough. “He asked me to gather up the men who were not wounded. There were only four of us left. He asked us to give covering fire while he made a dash to find a tank. He appeared on the top of the tank and directed fire which broke up the German counterattack. The Germans in disorderly fashion ran for their building. They started to open fire on us from there with automatic weapons. As he could not stop the withering fire he crouched on the tank and had it ram the first building. With his pistol in hand he wounded one German. After clearing the first building he had the tank move towards the building alongside. Before reaching the building he jumped off the tank to remove Lance Corporal Fraser’s body from the path of the tank. He had the tank fire a shell into the second building. The tank then gave covering fire while he himself cleared the building. He forced his way in the front door and alone cleared the building. He then continued across the road with covering fire from the tank and cleared the third building. We followed him from building to building gathering the prisoners. The last I saw of him was when he told me where to sight my Bren gun and then he dashed off to seek the company commander to tell him that the counterattack had been broken up and the objective taken.”

“I was Exhausted: Sick in Body, and Even Sicker in Spirit. For all My Exhaustion, I did not Sleep Well That Night.”

Sergeant Charles Anderson of the 6th Canadian Armored Regiment reported, “I, B19526 Sgt. Anderson C R, 6 Cdn Armd. Regt testify that during the battle of 26 February 1945 which took place after we had reached our objective [Mooshof], a Sgt of the Queen’s Own Rifles climbed on my tank and directed my fire upon the enemy who were making a heavy counterattack. Then he directed me toward some buildings where there were heavily held positions, all the while he was on top of the tank. In all his movements he was harassed by snipers. He directed me to ram the building with my tank which I did. After that he went into the building to clean out the enemy. He took several prisoners out of the building. The Sgt then went to other buildings to clean them out while my tank gave him covering fire. There was a great deal of sniping and mortar and shell fire during the whole action in which he directed my tank.”

Trooper Bill Adams was the driver in Anderson’s tank, and he later recalled ramming one of the buildings. “I put her in bull-low and advanced. When I hit, I bounced back about two feet and didn’t do too much. Then I tried again and this time I did a pretty good job and went in quite a way. I was pretty careful about ramming those stone walls. Usually there’s some kind of basement. We wouldn’t be much use to anyone with a 30-ton Sherman tank lying around in a cellar.”

Cosens had killed 20 of the enemy and taken 20 prisoners. He set out to report to Dunkelman but got only 25 yards before he was shot through the head by a sniper and killed instantly. His action was not only considered brave but decisive to the success of the whole attack. By taking and holding Mooshof, Cosens and D Company had seized their objective, allowing B Company to pass through to seize the battalion’s final objective. Thus, the right flank of the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade was protected as the division advanced to the high ground overlooking Calcar and on to Keppeln.

Apart from D-Day itself, February 26 was the hardest day of the war for the Queen’s Own. Company D had crossed the start line with 115 men. That night, Dunkelman was the only officer left standing. He could count only one NCO and 35 fighting men left. He later said, “I was exhausted: sick in body, and even sicker in spirit. For all my exhaustion, I did not sleep well that night.”

Although D Company was nearly destroyed, the action did not let up. The 4th Canadian Armoured Division had passed through while the Queen’s Own Rifles were engaged in Mooshof and advanced to the wooded Hochwald. In the forested area, infantry was needed, so the 3rd Division, including the Queen’s Own, was called upon to attack again. Tank support was nearly impossible, so the infantry went at it hand-to-hand with the enemy. What was left of D Company was in the thick of things, and Dunkelman’s leadership and bravery were rewarded with the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

The Queen’s Own Rifles remained in the line for two more weeks and then went into reserve until March 28 when they crossed

the Rhine to take part in the liberation of northern Holland. On May 5, the battalion was in Germany and attacking a crossroads near Ostersander. Then the cease-fire order was received, and the war in Europe was over. The First Canadian Army moved back into the Netherlands to rest prior to returning to Canada.

Angus Scully is an educator and historian. He is co-author of the book Juno Beach: Canada in World War II and has written several Canadian history textbooks. He lives in Georgetown, Ontario, and on an island in Lake Temagami in northern Ontario.

Excellent reading and obvious research. One of the best pieces I have read on the Canandian advancement post “Bulge”. On a par with Terry Copps works on the Canadians in the Italian Campaign, which is high praise.