By Michael D. Hull

After the collapse of Mussolini’s fascist regime in July 1943, the allies launched a double attack against the western coast of the Italian mainland. One of these was the U.S. Fifth Army’s amphibious assault—code named Operation Avalanche—against the historic port of Salerno, between Paestum and Maiori and 29 miles southeast of Naples. Major General Fred L. Walker’s 36th (Texas National Guard) Infantry Division, which had trained in North Africa, was part of Avalanche. Its 141st, 142nd, and 143rd Infantry Regiments, landed in the Paestum area on September 9.

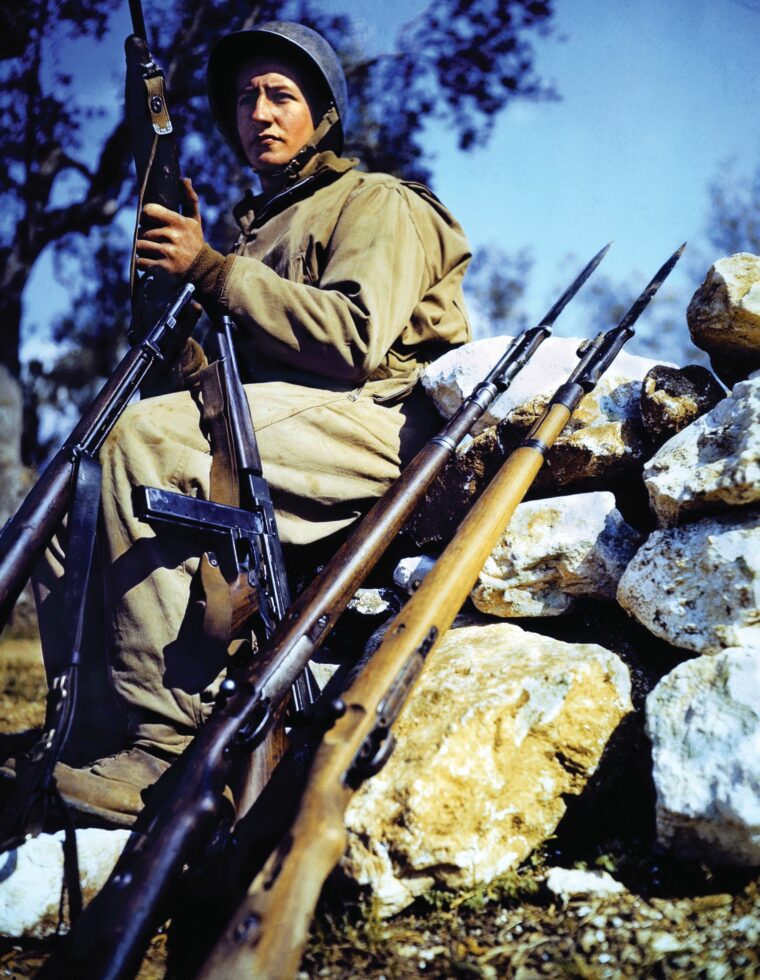

Corporal Charles E. Kelly, one of the non-commissioned officers in the division would emerge as a much-celebrated combat hero, with his extraordinary exploits at Salerno related in newspaper stories, magazine articles, and comic books.

Kelly, serving in the 143rd Regiment, was an Army maverick and former gang member in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who would be awarded the Medal of Honor and the nicknames, “Commando” and “One-Man Army.” A rebel against spit-and-polish who regularly volunteered for dangerous assignments, he seemed to many an unlikely candidate for the nation’s highest decoration.

The 22-year-old Kelly’s combat career began with an inauspicious splash at Salerno. Dog-trotting with a Browning automatic rifle from the fire-swept beach, he moved straight ahead. Passing a dead G.I. lying peacefully with his rifle beside him, Kelly averted his eyes and told himself, “Don’t let that worry you.” As German machine-gun bullets fell all around, Kelly jumped into a big drainage ditch for cover.

Weighed down by ammunition, he sank into water and slime up to his eyes. He dropped his BAR. Kelly spent several frantic minutes groping around for the weapon and then managed to pull himself out of the ditch by grabbing a branch on a nearby small tree. He then spent half an hour cleaning the trusty BAR as best he could and wiped off the photographs in his wallet. Enemy machine-gun bullets still bored into the ground around Kelly, and his staff sergeant fell with rounds in his head. Kelly hit the dirt, but kept trying to move forward. The next time he tried to check his position, he found himself alone.

The orders he had heard on the landing ship were gone from his mind, and all he could remember was someone having said, “When you get on the beach, keep moving forward.” So, Kelly moved on again, hopping over a wall, taking cover in thorn bushes, and searching for his company. After a while, he got tired of being doubled up and stooped over, so he boldly stood up and started walking. He stopped at a farmhouse well to get a drink and grab some grapes and peaches and passed deserted farms and houses. After walking for what seemed like about eight hours, Kelly guessed that he must be about a dozen miles inland.

Spotting a highway, he walked along it in the direction from which he had come. Then he saw German Mark IV medium tanks approaching. Diving into a ditch, Kelly aimed his BAR and opened fire as the tanks came close. The rounds made no impression. Kelly aimed at the slit openings, but the crewmen inside the noisy tanks were oblivious to the one-man attack. The tanks clanked past. Kelly continued along the highway and found a little creek, where he bathed his feet and washed his socks.

After reaching a winery and the 1st Battalion of his regiment, Kelly dug a foxhole behind a bush and fell asleep. On awakening, he continued along the highway to locate his company. He moved cautiously because the Americans and Germans had infiltrated each others’ lines. Machine-gun rounds still whizzed around him, but Kelly eventually found his outfit dug in, spread out in shallow holes. “I was sure they’d got you,” said his surprised lieutenant. “Where the hell have you been?” asked his comrades. They were amused by his predicament because he was a company malcontent.

Charles Kelly was born on Thursday, September 23, 1920, and grew up in a shabby tenement area on the tough north side of Pittsburgh. His family lived in a dilapidated shack in an alley behind a rundown apartment building. They had no electricity, and kerosene lanterns provided light. There was no bathroom, and the 11 Kellys had to share a fetid outhouse with several other families.

After finishing grade school, Charles helped to support his family by working as a paperhanger’s helper for $10 a week. The initial hard times became worse as the Great Depression gripped the country. Charles—a wiry, green-eyed youngster with a long face and a mop of wavy black hair—wanted to be a truck driver, but there were few jobs to be had. When idle, he roamed the streets with local gangs. He was arrested several times for being involved in brawls, but there were no convictions. Neighborhood patrolmen often administered their own brand of justice—a cuff around the head and a stern warning. They got to know Charles Kelly well.

In May 1942, the young man went off to enlist in the Army. He volunteered for the infantry. On the day before he left for basic training, Kelly confronted the policemen on the beat in his neighborhood and bragged, “I’ll go fight this war while you 4-Fs guard the vegetable wagons!” Then he strode away.

Barracks discipline was not to Kelly’s liking. His bunk was often rumpled at inspection time, his uniform was unkempt, and there was rarely a shine on his boots. He did, however, shoot expert on the rifle range. His unorthodox way of aiming—he sighted with his left eye instead of his right—did not endear Kelly to the drill instructors.

During training, the recruit from the wrong side of the tracks displayed an unnerving curiosity about explosives. He would unscrew the cap of a hand grenade and pour the powder out. And sometimes he would pull the fuse from a 60mm mortar shell and then shake it to see if anything rattled. “God, Kelly!” shouted a sergeant one day. “Do you want to blow us all up?”

After finishing basic training, Private Kelly decided to volunteer for the paratroopers. The tough training suited him, but a visit to a sick friend in the base hospital changed his mind. The sight of many airborne trainees with broken backs, arms, and legs was too much for him. He did not want to end up like that, but friends said that Kelly was obviously “not tough enough.” Depressed, he then went absent without leave.

Returning to Pittsburgh, Kelly told his family he had a furlough pass. But after three weeks, his relatives started questioning him, and rumors filtered through the neighborhood that he was a coward. When Kelly strolled disconsolately through an alley one night, two patrolmen cornered him. “You’re AWOL,” growled the older officer. “But now you’re going back, aren’t you?” The threat worked.

Dragged before a court-martial, Kelly pleaded guilty. He was given a 28-day restriction and was fined one month’s pay. Then he was shipped out to the 36th Infantry Division, which was staging at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, for overseas deployment. For the first time, the Pittsburgh outsider found himself at home in the Army. The boisterous Texans were as cocky and eager for a fight as he was, and the sergeants did not care which eye he used for aiming. They just wanted him to hit the target.

The Texas Division, which had been inducted at San Antonio in November 1940 and had trained in Texas, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Florida, shipped out from New York and arrived in North Africa in April 1943. It trained further at Arzew, Algeria, and Rabat, Morocco, before heading for the invasion of Italy.

After the bloody action in the Salerno bridgehead, the Texas Division and other reinforced Allied units began to push inland despite stiff German opposition. Kelly, a corporal in L Company of the 143rd Infantry Regiment, displayed skill and courage while volunteering for patrols to knock out enemy machine-gun positions. Then the company was ordered to head for the little town of Altavilla, perched on a vine-covered, terraced mountain about 10 miles from Salerno. Armed with 60mm mortars, the unit’s objective was to neutralize several enemy machine guns in the area, where there had been heavy fighting.

Late on September 13, 1943, Kelly and his comrades cautiously entered the town, pausing to shake hands with some residents and try to gauge the dispositions of the enemy. The GIs soon found out. Mortar shells exploded in the streets, machine guns chattered from rooftops, and snipers were all around. The Americans took up positions in the mayor’s house fronting the town square. It was a handsome three-story structure with thick stone walls. After checking every room to make sure there were no Germans inside, Kelly and his comrades hauled in their mortars, machine guns, cases of ammunition, and cans of water. The house was now an arsenal.

But German artillery on nearby hills zeroed in, and shells crashed into the stone walls, filling the house with smoke and dust. Soon, almost half of the original 100 G.I.s were casualties. Later on the evening of September 13, German infantry counterattacked Altavilla. American reinforcements tried without success to reach the town, and Kelly and the others were now surrounded.

The G.I.s fought back with rifles, mortars, machine guns, and hand grenades, and Kelly, the man who had washed out of airborne training, proved to be one of the toughest. His actions on that furious night would earn him the Medal of Honor and make him a national hero. He took an exposed position with his BAR in a third-floor window and rained fire on the attackers. Coolly and expressionless, Kelly enjoyed shooting the fanatical Waffen SS troopers who scrambled up to the house’s windows, blasting away with machine pistols. The ground was soon littered with gray-clad bodies.

Kelly fired his BAR until the barrel got so hot and warped that the rounds would not go through it. Then he used a 30-caliber machine gun to good effect and grabbed a Thompson submachine gun to mow down a squad of Germans entering the house’s courtyard. The fight continued through the night, but the besieged Americans were running out of ammunition. By the next day, September 14, there were no grenades left.

With the enemy threatening to overrun the position, Corporal Kelly resorted to desperate measures with some 60mm mortar shells which had been found on the third floor. There was no mortar barrel handy, so he grabbed the shells, pulled the safety pins, rammed the projectiles on the windowsill, and lobbed them down on the Germans below. There were deafening blasts, and the other G.I.s thought they were under artillery fire again. Kelly threw about half a dozen shells and killed at least five Germans. The rest fled.

By nightfall, only 28 members of L Company remained unwounded. The company commander decided that it was time to pull out, with the men sneaking out in groups of six, leaving the seriously wounded behind. Despite his sergeant’s injunctions, Kelly volunteered to stay and cover the withdrawal. There were still German troops in the area. As the G.I.s moved out, Kelly opened fire with a bazooka rocket launcher, but the back-blast knocked him off his feet. So, he grabbed a BAR and picked off Germans darting around in the dark. His unit withdrew successfully through an alley, and Kelly then left the house. Hiding in the shadows behind the building with the BAR at his hip, he waited for a group of enemy soldiers to emerge from the back door. When they appeared, he emptied his last two clips of ammunition and felled them all. Kelly then tossed his smoking weapon aside and made his way to the American lines. The Pittsburgh rebel who was “not tough enough” had dispatched more than 40 Germans in Altavilla.

An attempt by a battalion of the 142nd Infantry Regiment to capture Altavilla failed. Friendly artillery disintegrated the column, and the G.I.s fled in panic, shedding their weapons and equipment. Altavilla was lost, and General Walker had no choice but to redeploy his forces and shorten the Texas Division’s line. But the Allies, meanwhile, managed to stabilize the Salerno bridgehead and unleash tremendous firepower on the advancing enemy. By September 16, Field Marshal Kesselring was pulling back his hard-fighting panzers, aware that the British Eighth Army was advancing from the south. The armies of Montgomery and Clark linked up on the 16th, the bridgehead was finally consolidated on September 18, and British troops marched into Naples on October 1.

In January 1944, Kelly took part in the bloody action at the Rapido River, where the Texas Division was mauled. He took 44 men across the river, and only eight returned. During the bitter fighting around Monte Cassino, his company suffered such heavy casualties that Kelly, by then a sergeant, was the highest-ranking man alive.

On February 18, after the battered 36th Division had been pulled out of the line to a rest camp near Naples, Commando Kelly was awarded the Medal of Honor by General Clark. The citation acknowledged Kelly’s “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of life above and beyond the call of duty.” The first enlisted man to receive the decoration on the European continent had proved that he was indeed “tough enough.” Four days later, with the medal stuffed in a pocket, Kelly went back into action. He was also awarded two Silver Stars for heroism in action, the Combat Infantryman Badge, two Bronze Stars, and British and French decorations.

A few weeks later, in April 1944, Kelly received the greatest award of all: he went home. Late that month, he was joyfully reunited in Pittsburgh with his mother and brothers George, Danny, Eddie, John, Jimmy, Eugene, and Frank, six of whom were also in uniform.

Soon returning to duty, Kelly toured the country with a group of other combat veterans as part of the Army Ground Forces’ “Here’s Your Infantry” program, demonstrating battle techniques and selling war bonds. When the tour ended, Kelly was assigned to the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was discharged with the rank of technical sergeant in 1945.

Kelly tried to stay out of the limelight after the war, but his fame was too great. Like several other World War II heroes, including the famed Audie Murphy, Commando Kelly encountered daunting challenges in adjusting to civilian life.

Eventually, Kelly found work as a house painter and moved with his wife Betty and their six children to California and then Washington, D.C. But life grew even harder for Commando Kelly, plagued with continuing financial difficulties, problems with alcohol, and poor health. The former national hero spent the rest of his years in relative obscurity.

Just before Christmas 1984, he was admitted to the Veterans Administration Hospital in Pittsburgh, suffering from kidney and liver failure and an intestinal ailment. After undergoing surgery, he died on Friday, January 11, 1985, at the age of 64.

About 150 relatives and veterans paid their last respects to Commando Kelly at a north side funeral home on the following Monday. The mourners then followed Kelly’s flag-draped coffin to the Highwood Cemetery on a snowy hillside a few miles away. There, white-helmeted riflemen fired an 18-gun salute, the colors were folded and presented to Sergeant Kelly’s daughter, Virginia Ellen Shepherd, and a bugler sounded taps.

An old friend, Leonard Funk, of nearby Braddock Hills, Pennsylvania, who also received the Medal of Honor, recalled meeting Kelly in 1945. He said the two of them did not talk much about the war. “We know what it is,” said Funk. “We’d discuss other things than combat, you know. Try to forget that stuff.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments