By Sam McGowan

During the 1920s, roughly two decades before the B-25 Mitchell bomber came into service, U.S. Army Air Service commander Brig. Gen. William C. “Billy” Mitchell drove himself into an early grave while frantically trying to convince the ground-bound generals of the U.S. Army that the airplane was the weapon of the future.

Mitchell’s efforts reached the point of insubordination, for which he was court-martialed in the fall of 1925 and suspended from further service for five years. The verdict led Mitchell to resign from the Army, and he soon succumbed to the ill health his battle had earned for him. But his name would live on in the tactics he had advocated and in the bomber that was named in his honor.

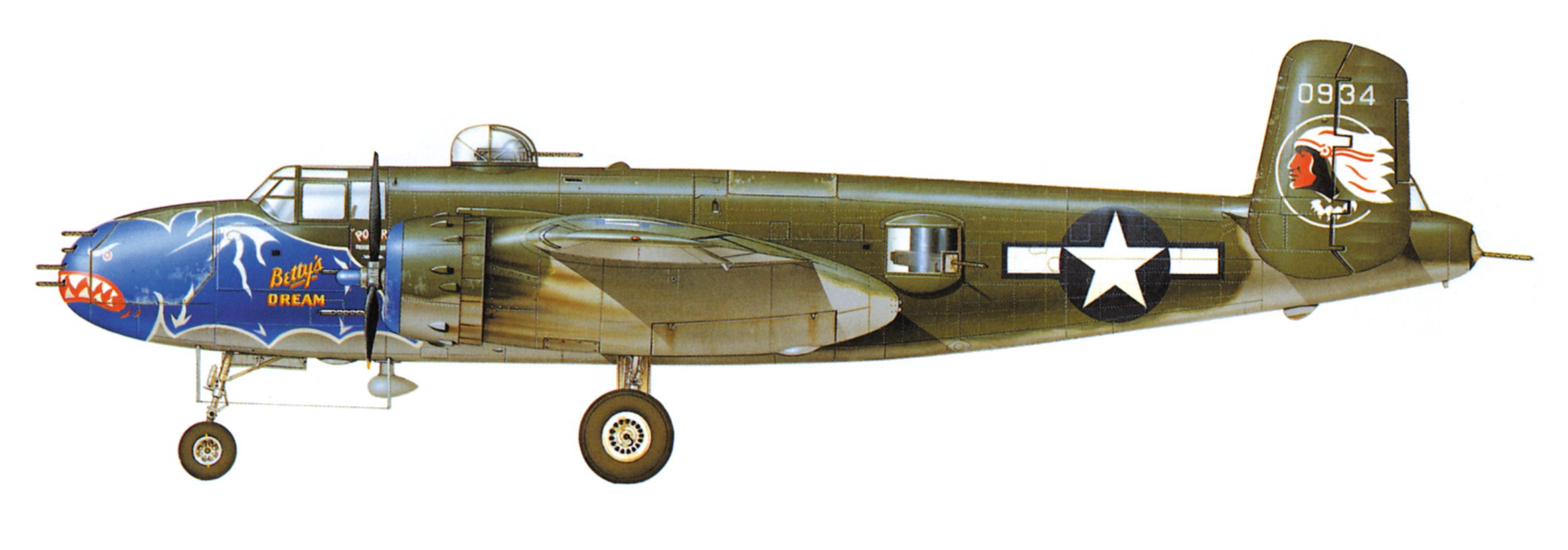

In 1939, the U.S. Army Air Corps put in an order for new class of “medium” bomber that would fall between the light bomber, as represented by the Douglas B-18, and the heavy bomber, which was symbolized by Boeing’s famous B-17 Flying Fortress. The proposal called for a twin-engine plane capable of flying 300 mph, carrying a 3,000-pound bomb load, and having a 2000-mile range.

Four aircraft manufacturers designed and built airplanes for the role, and the Army decided to accept both Martin and North American’s types, with the Martin designated as the B-26 and the North American as the B-25. North American executive Lee Atwood suggested that the company’s new bomber be called the “Billy Mitchell” in honor of the controversial general.

Doolittle Sought Experienced B-25 Mitchell Bomber Pilots for a Secret Mission

The first B-25s were delivered to the 17th Bombardment Group at McChord Field outside of Tacoma, Wash., in 1941. The War Department also approved the sale of several Mitchells to the Dutch government-in-exile for service with the Netherlands East Indies Air Force in Southeast Asia, but deliveries had yet to commence when war came. When the United States entered the war, the 17th Bombardment Group was the only operational B-25 group; the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron was also equipped with Mitchells, as was the 39th Bombardment Squadron, which flew them on antisubmarine patrol on the East Coast with the 13th Bombardment Group.

Having moved to Portland, Oreg., from Tacoma, the 17th’s squadrons were put to work patrolling the South Pacific Coast for several weeks. In February, the group moved across the country to Columbia, SC, to join the new Eighth Air Force, which was being formed to support the planned invasion of North Africa. They soon had a visit from Lt. Col. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, who had been assigned to a special project by Army Air Corps commander General Henry H. Arnold. Doolittle was looking for experienced B-25 pilots to volunteer for a secret mission.

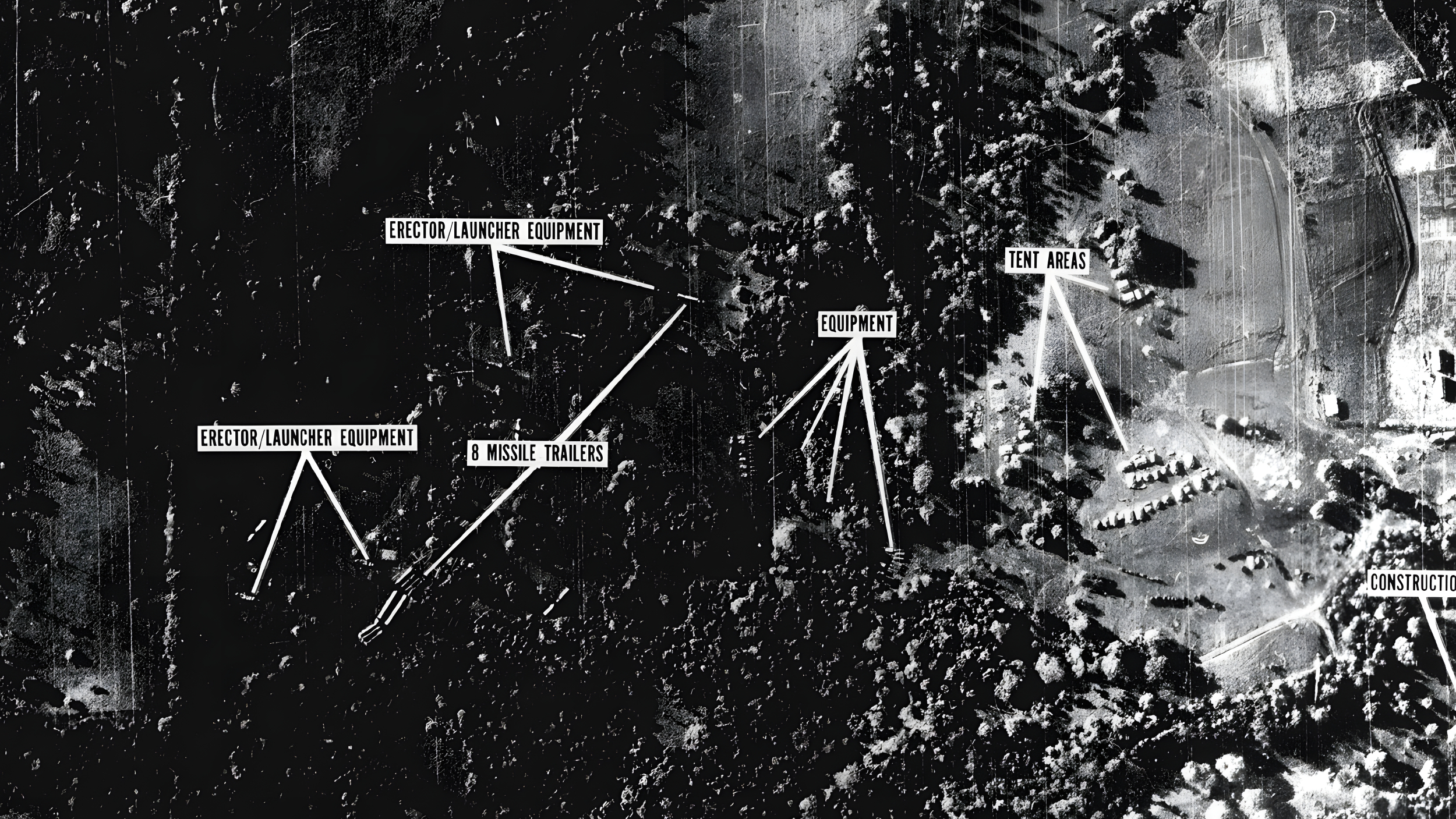

Doolittle stated in his autobiography that his project was one of several that were planned for a buildup of American air power on the Chinese mainland. The War Department planned to establish a heavy bomber group equipped with Consolidated Aircraft B-24 Liberators, a fighter group equipped with Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, a transport group equipped with Douglas Aircraft C-47s, and a medium bomber group of B-25s in China. Arnold chose to have one squadron of B-25s delivered to China by aircraft carrier, with an en route flyover of the Japanese main island on the way, in response to a White House request for a mission to bomb Tokyo.

As the project officer, it was Doolittle’s task to organize the mission, determine the proper aircraft, find and train the crews, then coordinate their movement to the West Coast. He was not the commander, nor was he supposed to go on the mission. Launching the mission from an aircraft carrier limited the choice of bombers to just two: Martin’s B-26 and North American’s B-25. Doolittle decided to use Mitchells. After recruiting enough crews from the 17th Bombardment Group and the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, Doolittle put them through a short training program at Eglin Field, Fla., where they learned to take off in the shortest possible distance.

On April 1, 1942, the 16 B-25s were loaded on board the carrier USS Hornet at Alameda, Calif. Doolittle had managed to get a semblance of permission from General Arnold to lead the mission himself. Eighteen days later, he and his men flew into the pages of history.

None of the B-25s Were Lost in Enemy Space

In a military sense, the Doolittle Raid was a failure. The small task force of which he and his crews were the centerpiece was detected while Hornet was still 150 miles short of the intended takeoff point. The B-25s were launched on a contingency plan to save the carrier– to clear the flight deck so its fighters could be positioned for launch to defend against attack. Doolittle and the Navy had agreed to sacrifice the bombers in the event the task force was detected by the Japanese. With the task force having been spotted, the mission had been compromised and the airplanes were sent out with the crews knowing it was unlikely that they would reach China.

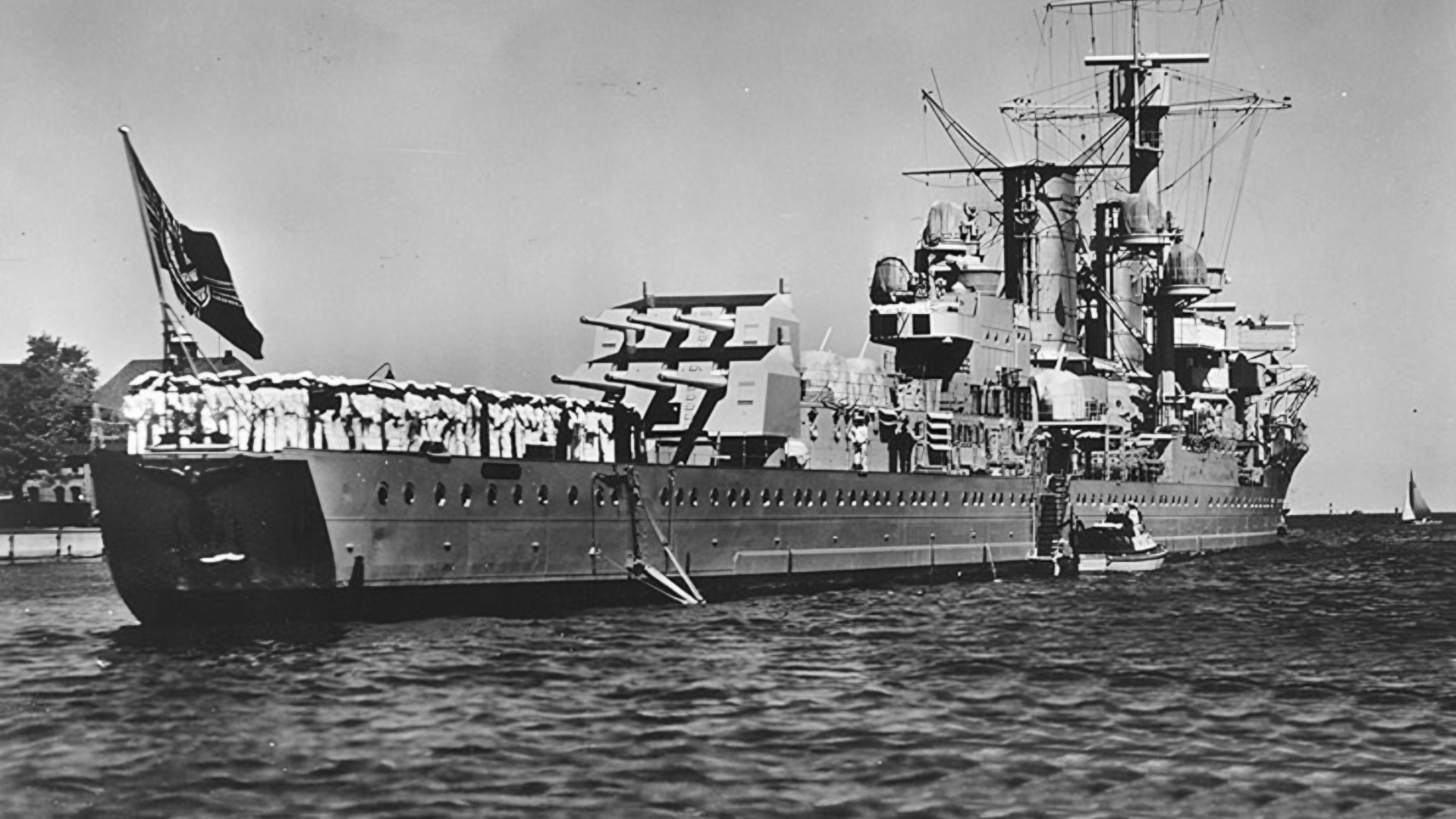

Although the B-25s managed to achieve the element of surprise, the military effectiveness of the raid was minor, even though all of the B-25s bombed successfully, reportedly on military targets, and none were lost in enemy airspace. One crew reported hitting the Japanese carrier Ryuso, which was resting in dry dock at Yokosuka Naval Base.

The Tokyo Raiders were blessed with a fortuitous east wind that allowed them to cover the distance across the East China Sea to the vicinity of Chuchow, where they were supposed to land. Without the wind, it they might not have reached land at all. When they reached the Chinese coast, however, their luck ran out—darkness had fallen and low clouds and rain shrouded the region. Furthermore, the raiders were two days early and the Chinese had not been alerted to expect them, in part due to the secrecy surrounding the mission.

The airfields where they were supposed to land had not been illuminated so the bomber pilots could find them. Confronted by miserable conditions and unable to locate the landing strips, some crews elected to take to their parachutes, while a few others decided to take their chances with emergency landings. Although all of the crew members but one survived the bailouts and crash-landings, not a single airplane arrived in China intact.

One crew ended up in Russia, and two crews came to earth in Japanese-held territory. They were captured and put on trial as war criminals. Three men were executed, but four finished the war as POWs. One, former Corporal Jake DeShazer, returned to Japan after the war as a Baptist missionary. A Baptist missionary already in China, a young man named John Birch, guided Doolittle and his crew—as well as several other raiders—to safety.

Doolittle recommended the young man to General Claire Chennault. Captain John Birch would become a hero of the war in China for his efforts as an intelligence officer operating deep inside enemy territory. One of his responsibilities was directing B-25s against targets deep inside Japanese-held parts of the country.

Doolittle’s Medal of Honor

Doolittle believed that the mission was a failure. He knew the importance of the B-25s to the war in China and how their loss would delay Allied efforts in the region. As it was, the first intact B-25s did not arrive in the China-Burma-India Theater until September. He fully expected to be subjected to a court-martial when he returned to Allied control. Instead, he was welcomed as a hero and awarded the coveted Medal of Honor, which he did not believe he deserved.

The Chinese who had provided sanctuary for Doolittle and his men were not so lucky. The Japanese went on an offensive to capture all territory from which bombers could attack Japan, including the region around Chuchow. In the process, they killed a quarter-million Chinese. They also undertook the task of building a defense against future air attack, a military element that had previously been lacking in Japan because of the distances involved in striking the islands. Japan also increased its offensive operations in the Southwest Pacific, moving farther southward in the Solomons and along the shores of New Guinea toward Australia.

The mission was a success as far as the White House was concerned. Newspapers trumpeted the news that Tokyo had been bombed, thus bringing a lift in morale to the American public and helping guarantee President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s reelection to an unprecedented third term in November.

The takeoff from the carrier Hornet for the raid on Japan was not the first time a B-25 had flown off of the decks of a carrier, nor for that matter was it the first from Hornet. In early 1942, right after the 39th Bombardment Squadron switched from B-18s to B-25s, three squadron crews took three airplanes to the naval airfield at Norfolk, Va., to test their airplane’s short-field takeoff and landing capabilities.

After practicing on a 500-foot stretch of runway that was painted to represent the outline of a carrier deck, the three B-25s were loaded on Hornet and taken 100 miles out into the Atlantic. With the carrier headed into a 20-knot wind, the three B-25s took off and flew back to Norfolk. The tests were reportedly observed by Jimmy Doolittle, who at the time was a special projects officer assigned to, U.S. Army Air Corps headquarters. Whether or not Doolittle was already working on plans for the raid on Japan at this point is difficult to say. He does not mention the trials in his autobiography.

According to the lore of the Doolittle Raid, the idea came from a U.S. Navy officer who claimed he was flying over Norfolk and looked down and saw Army bombers taking off from the outline of a carrier deck that had been marked on the runway. He is supposed to have taken the idea to Admiral Ernest J. King, the chief of naval operations, who took it to President Roosevelt. The pilots were not told the purpose of the tests, but surmised that they were to determine the feasibility of using aircraft carriers to deliver B-25s to the combat zones. Perhaps the tests were for that purpose and they were classified to protect future carrier deliveries.

The Doolittle Raid on Tokyo is the most famous mission flown by B-25s, but it was far from the most important, nor was it the first. Several weeks before Jimmy Doolittle led his men off of Hornet on what the crews thought was a suicide mission, a seemingly insignificant event occurred at an airfield near Melbourne, Australia. On March 27, 1942, a C-47 landed at the airfield where a dozen or so B-25s that had been consigned to the Dutch had been parked after being ferried from the United States. Out of the airplane stepped Lt. Col. John “Big Jim” Davies, the former commander of the 27th Bombardment Group and the new commander of the recently arrived Third Attack Group. (Read more about the Doolittle raid and the events that defined the Pacific Theater inside WWII History magazine.)

“Pappy’s” Contribution

Davies was accompanied by two dozen of his pilots. One of the pilots was a formerly retired US Navy enlisted pilot who was now Captain Paul I. Gunn, U.S. Army, and the commander of air transport in Australia. Davies found the officer responsible for the airplanes and presented orders transferring them to the U.S. Army and authorizing him and his crews to pick them up and take them north. The orders had been obtained from Brig. Gen. Eugene Eubank, commander of V Bomber Command, through a process of shuck and jive that Gunn suggested to Davies after he found the brand-new airplanes sitting idly on a ramp after their delivery to Melbourne.

P.I. Gunn, or Pappy, as the men of the Third Attack Group had begun calling him, was one of the true characters of World War II, and one of the most important. Author Walter D. Edmonds would say of him, “No other person below senior officer rank would make as much of a contribution to the war in the Pacific,” and much of it would involve the B-25. In fact, it was Gunn who first learned that the B-25s were in Australia, and it was he who concocted the plan to literally steal them from the Dutch.

As far as Gunn was concerned, it was a tragedy for the B-25s to sit idle until the Dutch could train crews for them when there were available American and Australian aircrews with a war to fight. Furthermore, once Davies and his men returned to their base at Charter Towers and discovered that there were no bombsights for the airplanes, Gunn returned to Melbourne and got them. According to the men of the Third Attack Group, when the Dutch refused to give up the bombsights, Gunn presented his authority in the form of a Thompson submachine gun—and got the bombsights.

Naturally, Gunn took one of the airplanes for himself. With the scrounging of the B-25s, Gunn became a member of the Third Attack Group the following day; he was relieved of his duties as commander of the 21st Transport Squadron and transferred to the bombers on orders dated March 28, 1942.

Until Davies and Gunn purloined the B-25s, the only U.S. offensive aircraft in Australia were a few Douglas A-24 Dauntless dive-bombers that originally had been bound for the Philippines and which had just returned from Java, and a handful of war-weary Boeing B-17s. A B-26 group was on the way to Australia, but would not become operational for several weeks.

The B-25s Dropped Four 300-Pound Bombs on the Airfield

Although the Dauntlesses would devastate the Japanese fleet at Midway a few weeks later, they were poorly suited for the kind of combat Allied aircrews were enduring in New Guinea. They lacked the armament for self-defense and were so slow that Japanese fighters could easily intercept them. After particularly heavy losses on a mission to Buna in July, Colonel Davies decreed that none of his men would go into combat again in the slow and poorly armed dive-bombers. Consequently, the B-25s were a godsend.

By April 6, while the Tokyo Raiders were crossing the Pacific on the Hornet, Pappy Gunn had the B-25s ready for combat and they flew their first mission against the Japanese airfield at Gasmata. Each of the 12 B-25s dropped four 300-pound bombs on the airfield, with about half of them exploding among the parked airplanes. Suddenly, the Japanese were suffering the experiences of the Americans at Clark Field on December 8, 1941. Reportedly, at least 30 Japanese bombers were destroyed in the attack.

On December 21, 1941, all U.S. B-17s of the 19th Bombardment Group in the Philippines had been ordered to Australia. There they joined elements of the newly arrived 7th Bombardment Group on missions staging from Northern Australia through Mindanao. A brand new airfield had been constructed for the B-17s some 45 miles out of Darwin and named Batchelor Field in honor of a prominent Australian family.

It had been several weeks since the last raid in the Philippines, and General Ralph Royce wanted to fly another mission against the Japanese in hopes of relieving some of the pressure on the embattled troops on Corregidor. Ten B-25s would join three 7th Group B-17s on the mission. Staging from Del Monte Field on Mindanao, the Royce Mission B-17s attacked Nichols Field at Manila while the B-25s went after Japanese shipping at Davao and Cebu, with some success. Several Japanese ships were sunk, including one hit by Pappy Gunn. All of the airplanes returned safely to Del Monte. A Japanese air strike knocked out one of the B-17s and damaged the other two, but the B-25s were unscathed.

The next morning, April 14, the B-25s struck Davao and Cebu again. The Japanese air raid replied with another that afternoon, but missed the camouflaged U.S. bombers. That evening word reached the airfield that Japanese troops were 24 hours away, so Royce decided to leave for Australia the next morning. The two surviving B-17s were patched up, and all 14 airplanes took off for Darwin. Unfortunately, they were only able to take 50 American airmen from Del Monte with them.

The last airplane to return to Batchelor Field was Pappy Gunn’s. Just why the veteran military aviator was so far behind the others is unclear. The official version is that the long-range Benson tank for his airplane was damaged in a strafing attack, but it is also possible that he flew another mission on the side. At some point, either during the Royce Mission or sometime afterwards, Gunn landed a B-25 Mitchell bomber on a beach to pick up a young Japanese-American intelligence specialist who was being brought out of the country after having infiltrated the Japanese Headquarters in Manila. Nat Gunn, Pappy’s son, believes his father made the dangerous pickup during the Royce Mission.

Flying Just Over the Tree Tops to Avoid Detection

Before he was ordered to Australia in late December 1941, and on subsequent missions when he went back in his personal Twin Beech, Captain Gunn had flown all over the Philippines transporting personnel and cargo in skies that crawled with Japanese planes. To avoid detection, Gunn flew low, as low as he could, which meant right down on the treetops! He rarely flew above 500 feet. His experiences taught him that the pilot who stayed down on the deck had the element of surprise, and while he flew his unarmed transport around the Philippines, he thought of how heavily armed aircraft should be capable of successful strafing attacks.

The heavy losses of the Third Attack Group’s A-24s made Gunn seek to turn the B-25s into gunships. In June 1942, North American technical representative Jack Fox sent a set of drawings Gunn had worked up showing .50-caliber machine guns mounted in the bombardier’s station to the factory in Long Beach, Calif. At the time, there were still too few B-25s for any to be spared for modification, so Gunn turned his talents to modifying the Third Group’s Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers when they arrived in Brisbane in July.

In early August, Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney arrived in Australia to take command of the air war. During a visit to the Third Attack Group at Charter Towers, an airfield south of Townsville, a few days after his arrival, he was introduced to Pappy Gunn. At the time, Gunn was in a shelter working on the conversion of a recently arrived A-20 from a light bomber into a strafer. His conversion involved removing the bombardier’s station and replacing it with four .50-caliber machine guns, with two others mounted on the sides of the fuselage.

When Gunn told Kenney that the guns came from wrecked fighters, Kenney knew he had met an innovator. The spark began to glow that led to the conversion of the B-25 from a medium bomber into the most potent weapon of the Pacific War. Gunn told Kenney that as soon as he had converted all of the A-20s, he wanted to start work on a B-25. Kenney told him to hold off for the time being, and that as of that minute, Gunn was now a member of his staff and in charge of special projects.

A few weeks later, Kenney gave Gunn the go-ahead to begin the conversion of a B-25. Gunn, who was now a major, worked out a design that packed six .50-caliber guns in the nose of the airplane, with two more mounted on each side in pods.

Pappy’s Folly

When Kenney came out to look at the prototype, he asked Gunn, “What about the CG (center of gravity)?” Gunn replied, “Oh, we threw that away to save weight!” In truth, the first airplane was so nose-heavy that it wouldn’t fly, but Gunn solved the problem by moving the pod guns farther aft and relocating the fuselage fuel tank to bring the CG within the proper range. His ground crew named the airplane Pappy’s Folly after the failed attempt to fly. Pappy Gunn took the modified B-25 up to Charter Towers and on to New Guinea to demonstrate it to the Third Attack Group pilots and to let some of them fly it.

After Gunn proved that the conversion would fly, Kenney authorized the conversion of 12 B-25s, enough to equip a full squadron. Gunn had performed the initial modification at Eagle Farms Field at Brisbane, and the depot there began work on the additional Mitchells using the plans Gunn had drawn up. On December 16, Captain Ed Larner, commander of the 90th Bombardment Squadron, led a flight of six converted B-25s on a mission against Salamaua. Each airplane carried a load of parachute/fragmentation bombs in addition to their guns. The low-level attack caught the Japanese by surprise, and the awesome firepower of the “strafers” was devastating as they destroyed dozens of Japanese planes.

The power of the B-25 strafers was demonstrated to the world in early March 1943, when the Third Attack Group delivered the knockout blow to a 14-ship Japanese convoy that was sitting just outside Lae Harbor during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. A low-level strafing and skip-bombing attack by 12 modified B-25s and a dozen A-20s left every single transport and most of their escorts either sinking or badly damaged. Naval historian Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison referred to the attack as “the most devastating attack of the war by airplanes against ships.”

Kenney left for the United States immediately after the Bismarck Sea battle. When he arrived in Washington, he told General Arnold that he wanted several squadrons of factory-modified B-25 strafers. When Arnold called in his engineers to discuss the project, they told Kenney that it was impossible. Kenney told them that not only was it possible, but a squadron of so-modified B-25s had played a major role in the just-completed battle!

Arnold then told Kenney he wanted to bring Pappy Gunn back to the States to work in engineering, a proposal the Fifth Air Force commander immediately protested. Kenney managed to evoke a compromise whereby Gunn would return for a few weeks during which he would visit the engineering facilities at Wright-Patterson air base in Ohio, and then stop by the North American factory at Long Beach and show them how to make the conversion so it would not have to be done in the field.

While he was in Long Beach, the North American executives showed Gunn their newest version of the B-25, the G model, which featured a 75mm cannon installed in the bombardier’s tunnel. Gunn was very impressed with the concept, but he felt that the airplane needed several other modifications to make it suitable for combat. Gunn’s other modifications included the removal of the belly turret since the strafers flew so low the guns were useless anyway, and the addition of waist and tail guns to continue strafing as the airplane passed over and pulled away from the target.

Powerful Gunship or Disappointment?

When the first B-25G arrived in the Southwest Pacific, Kenney put Gunn in charge of testing it and making any needed modifications. Unfortunately, North American had sent the first airplanes out without the changes Gunn had suggested, so they had to be made in the field, a process that delayed their entry into combat.

Although the cannon-equipped B-25Gs are often pointed to as powerful gunships, in reality they were a disappointment. The cannon had to be loaded by hand, which restricted a pilot to no more than two shots during an attack, and usually just one. A single cannon shot would do little to deter the gunners on a target ship during a skip-bombing attack. The crews believed another pair of .50-caliber guns would be more effective and, ultimately, the cannon was removed from the Fifth Air Force B-25Gs. Pappy Gunn did work up an installation for a 37mm automatic cannon in the nose of a B-25, but the design was never adopted.

North American also came out with a model, the B-25H, which was designed to be flown without a co-pilot, a feature to which General Kenney strongly objected. He felt that two pilots were absolutely necessary for the long flights characteristic of the war in the Southwest Pacific. The factory production model that really filled the bill was the B-25J, which came equipped with 12 forward-firing fixed guns as well as a feature that allowed the top turret guns to be synchronized with the fixed guns for a total of 14. The B-25J also featured an interchange capability that allowed the airplane to be converted from a strafer back to a medium bomber if desired. The J was the most successful of all of the B-25 Mitchell bomber models.

With the failure of the 16 Doolittle B-25s to reach China, the Mitchell’s entry into combat in the China-Burma-India Theater was delayed for several months. The 341st Bombardment Group finally arrived in the theater in September, but it was several weeks before the squadrons were ready for combat. One squadron, the 11th Bomb Squadron, was detached to Claire Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force for duty in China proper.

The B-25s in CBI functioned as both medium bombers and in the ground attack role. Traffic on the Burmese railroads was a major target, with particular emphasis on bridges. Mitchell crews in CBI attempted to knock out bridges with skip-bombing, but the bombs often passed beneath the spans without damage. The 490th Bomb Squadron was responsible for attacking bridges, usually without success, until a fortuitous event led to the development of a new technique. Major Robert Erdin pulled up to miss a tree just as he dropped his bombs on a skip-bombing run, causing the bombs to fly upward in an arc.

Erdin assumed the bombs would miss completely, but his crew looked back and saw two spans falling into the river. It turned out that making a shallow dive and releasing the bombs right at pull-up caused them to strike the target at just the right angle. Bridge-busting then became a major B-25 mission in CBI.

North Africa and the Mediterranean saw large numbers of B-25s, beginning with the arrival of the 12th Bomb Group in North Africa in August 1942 to support the British. Three other groups reached the theater by the end of the year: the 310th, 321st, and 340th Bombardment Groups. For the most part, B-25s in the Mediterranean Theater functioned as medium bombers, although 16 airplanes were modified to strafers in the spring of 1943 for an unspecified mission (probably attacking Axis shipping in the Mediterranean). They were later returned to medium bomber configuration.

After Defeating the Afrika Korps, The Allies Marched Northward

Several B-25s were involved in the successful interception and destruction of dozens of German Junkers transports that were attempting to bring reinforcements to the Afrika Korps in North Africa. Whether the B-25s were used to attack the German transports or just to locate them for the P-38, P-40, and Spitfire fighters is unclear.

With the defeat of the Afrika Korps, the Allies moved northward, first landing on Sicily then on the Italian mainland. Mitchells were heavily involved in the preparation for the landings and as medium bombers throughout the Italian Campaign. In late 1943, all of the B-25s were rolled into the Twelfth Air Force to support tactical operations in the theater. The Mitchells serving in the Mediterranean were the only American B-25s to fight in the European Theater. No U.S. B-25 groups were ever based in the United Kingdom. The B-25s joined with B-26s in attacks on tactical and strategic targets such as railroads, bridges, and troop concentrations.

Mitchells also served at the top of the world, where they replaced a squadron of B-26s that had moved north to Alaska in early 1942. The Eleventh Air Force Mitchells operated as medium bombers attacking Japanese targets in the Aleutian and Kurile Islands. The U.S. Navy also operated Mitchells, which they designated as PBJs. The Doolittle mission had proved that Mitchells could take off from a carrier; the Navy ran a series of tests to see if they could also land aboard one. While the takeoff and landing tests were successful, the Navy never developed the idea for operational use.

Beginning with the sale of B-25s to the Dutch, North American produced thousands of Mitchell’s for other nations. Considering that the Fifth Air Force was originally headquartered in Australia, it was only natural that the Royal Australian Air Force would operate B-25s of its own. A little-known fact of World War II in the Pacific is that when the 90th Bombardment Squadron was first equipped with B-25s, there were not enough American pilots and gunners to man them. To fill the gap, several RAAF airmen volunteered to fly with American pilots. Most of the co-pilots and many of the gunners in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea were Australian.

Several RAAF squadrons equipped with Mitchells saw action in the East Indies. The British Royal Air Force received almost a thousand B-25s, as did the Soviet Union. The Chinese Air Force also operated B-25s.

The name “Tuskegee Airmen” is often associated with the 332nd Fighter Group, which saw combat in the Mediterranean, but the African American pilots who trained at Tuskegee University in Alabama were not all fighter pilots. Bombardiers, radio operators, and gunners, were combined to make up an all-black group equipped with B-25s. The group was still in training when the war ended and never got overseas.

B-25 Mitchell Bomber Crews Pressed Their Attack in Spite of Fierce Japanese Aggression

While they served honorably in all theaters except Western Europe, and in the colors of several nations, it was in the Pacific, particularly the Southwest Pacific, where the B-25s achieved their greatest successes. General Millard Harmon, commander of the Thirteenth Air Force, sent some of his B-25s to Brisbane for conversion, and then his own engineers began converting airplanes at their depot at Tontouta. The Tenth Air Force in India also picked up on the strafer modifications.

One of the most dramatic B-25 attacks of the war was the penetration of Simpson Harbor at Rabaul on November 2, 1943. Lt. Col. John “Jock” Henebry, commander of the Third Attack Group, led the air assault into the harbor. It was not the first time the B-25s went to Rabaul–they had flown several missions against the airfields around the fortified city–but it was their first attack against the shipping in the harbor. A total of 75 Mitchells from the 3rd, 38th, and 345th Bombardment Groups were on the mission, with escort provided by 107 Lockheed P-38s.

In spite of aggressive opposition by hordes of Japanese fighters, the B-25 crews pressed their attack. The 3rd Group claimed 50,000 tons of enemy shipping sunk, while the 38th claimed 40,000. The 345th had gone against the airfield at Lakunai. The total tonnage sunk was greater than either the Battle of Midway or the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

It had not been without cost. Eight B-25s and nine P-38s were lost, along with their crews. One of the pilots lost was Major Ray Wilkins of the Third Attack Group. His plane was hit repeatedly by antiaircraft fire, but sank a destroyer and opened up a path for the other airplanes in his group to attack. Wilkins was awarded the Medal of Honor. Jock Henebry’s Mitchell was shot up by fighters and lost an engine, but he made it to an emergency landing strip on an island off the New Guinea coast. His friend Chuck Howe landed behind Henebry and picked him and his crew up for the return to Port Moresby.

The B-25 continued to be the preferred medium bomber in the Pacific until the war’s end. The Army Air Forces leadership wanted to replace it with the new Douglas A-26 Invader, but the design was flawed and the modifications required to correct the problems delayed the airplane’s entry into combat. General Kenney did not want the Invaders anyway; he was happy with the B-25s and A-20s in his command.

Several B-25 squadrons had moved on to Okinawa in preparation for the invasion of Japan and were flying missions against the Japanese Home Islands when the war ended. Along with the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, the North American B-25 Mitchell had been in the war virtually from the beginning to the very end.

My Father was an armourer with 2 squadron RAAF, I think I remember him saying that the Aussie Mitchells had 20 mil. cannons as cheek guns but have been unable to confirm this. Does anyone have an answer please?