By Eric Niderost

In normal times 18th-century Cambridge, Massachusetts, was a small farming community of about 800 souls clustered around a common. Some of its more prominent citizens owned stately Georgian homes, and Cambridge also was the site of Harvard College.

In the summer of 1775 Cambridge was an armed camp, home to thousands of men who called themselves “forces of the United Colonies.” Mostly New Englanders, these militiamen were mainly farmers and craftsmen, and at the time they were conducting a siege of nearby Boston, which was occupied by British Army regulars.

They were largely untrained, but some of these men had already shown their mettle at the Battle of Bunker Hill, fought earlier that summer. The British redcoats had marched confidently forward with parade ground precision, only to be swept away in a storm of lead unleashed by hundreds of American muskets, fired by men protected by ramparts on a high hill.

The British finally took the American position, but it was a pyrrhic victory with more than 1,000 redcoat casualties. “Another such [victory],” lamented British General Henry Clinton, “would have ruined us.” The myth was soon born that Americans were a tough, resourceful breed that did not need any formal training or discipline to win a war.

The roots of the American Revolution can be traced back to 1765, when Great Britain, saddled with a huge war debt from the Seven Years War, attempted to impose its authority with a series of direct taxes enacted by parliament. To the Americans this was tyranny and arbitrary rule, since it seemed to usurp the powers of their own colonial legislatures.

After the clashes at Lexington and Concord, the members of the Second Continental Congress decided to take measures for their mutual defense. The thousands of militiamen besieging Boston were adopted as the nucleus of a United Colonies Army, later refined to the Continental Army. As time went on, men from New York and other colonies joined the fledgling force.

As soon as the Continental Army was created, it was recognized that a commander in chief was needed to give the fledgling force strong leadership. George Washington was chosen in part because he was a Virginian, and so far the troubles had been largely confined to New England. He was also one of a handful of native-born Americans with any real, albeit limited, military experience.

Publicly it seemed nothing could shake Washington’s calm, even placid, demeanor. But when he inspected his new command he was appalled. The general later wrote that the Continental Army was “a mixed multitude of people under very little discipline, order or government.” Officers were mainly elected; if soldiers did not like their orders, the offending leader was quickly demoted and replaced.

During Washington’s inspections, scattered popping noises rippled through the camp, the sounds of soldiers randomly discharging their muskets. This had nothing to do with Washington, nor was this a form of salute. Soldiers would fire flintlocks to start fires, to empty weapons, or just to have some fun. The men were so careless that companions were sometimes killed or wounded.

On August 4, 1775, a general order was issued, noting that “it is with shame and indignation the general observes, that notwithstanding the repeated orders which have been given to prevent the firing of guns in and about camp, it is daily and hourly practiced.” Such carelessness produced casualties, created chaos, and used up powder. It was a closely guarded secret, but for a time in summer 1775 the army had only 36 barrels of powder.

The Massachusetts legislature warned Washington that this rag-tag collection of farm boys were “youth … used to a laborious life” who had not learned “the absolute necessity of cleanliness in their dress and lodging, continual exercise, and a strict temperance, to preserve them from diseases.”

The reality made these pronouncements seem like understatements. Men felt that doing the laundry was woman’s work, so they wore their clothes until filthy and stinking with sweat and other revolting odors. Not everyone was so dirty, but regular bathing was not as common in the 18th century as it was later. Filthy soldiers often developed “the itch,” a skin disease that left the victims with scab-like eruptions on their bodies. The cure was an ointment made of hog lard or pine tar mixed with brimstone.

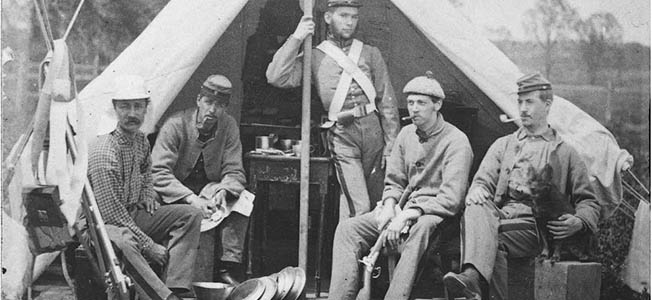

Cambridge was overflowing with men in the summer and fall of 1775. All classes at nearby Harvard College were cancelled, and its stately buildings were converted into makeshift barracks, a hospital, and officers’ quarters. But the army had nearly 20,000 soldiers, and those who were not housed in abandoned Tory houses or college buildings had to make do with the materials at hand.

Tents and other makeshift shelters sprang up in Cambridge common, each placed wherever the soldiers wanted them. The resulting confusion looked more like a gypsy camp, with little of the military precision, cleanliness, or order of European armies. Open latrines were dug at Washington’s instance, but all too often men would “set down and ease themselves” whenever they felt like it.

Human waste and offal from slaughtered animals was everywhere, and within a very short time a noxious cloud of evil smells rose from the camp. The acrid stench of urine and feces combined with the smell of gunpowder, green wood burning, and the rotting remains of animal carcasses produced an almost suffocating stink.

Unsanitary conditions bred disease. Typhus and smallpox were probably the greatest killers in camp, but soldiers also contracted dysentery and other illnesses. Smallpox was a viscious scourge, and in those years the civilian population experienced a terrible epidemic of this disease.

Washington was immune since he had had smallpox as a teenager, but he recognized what its deadly threat. He eventually made inoculation mandatory for the entire army, which undoubtedly saved lives. Sanitation slowly got better, though like any 18th-century army, disease would not be entirely eliminated.

Washington also recognized the desperate need for a trained and fully professional army, an army that could meet the British regulars on an equal footing and beat them. Washington wrote, “Discipline is the soul of an army. It makes small numbers formidable; procures success to the weak, and esteem to all.”

The peculiarities of 18th-century European warfare made discipline all the more important. The smoothbore flintlock musket was the basic infantry weapon at the time. It was a fairly reliable weapon, at least in comparison to the matchlock that it replaced, but was still wildly inaccurate. A soldier firing a musket was lucky if he could hit a target beyond about 50 yards or so. To compensate for this, European armies fired massed volleys in three ranks, usually at close range.

Muskets were unwieldy weapons, and loading was an intricate process that required several distinct steps. A soldier had to be a mindless automaton, or possess nerves of steel, to go through the motions of loading and firing in the open with cannon balls and musket bullets peppering the air all around him. Since few humans have nerves of steel, European armies resorted to flogging and other draconian punishments to enforce discipline.

On the whole, most Americans thought this was nonsense. New Englander Timothy Pickering, who wrote one of the early drill manuals, believed that Americans were intelligent people who fought by choice and used their brains. They did not need compulsion, and they certainly did not need intricate drill. Washington thought otherwise.

Americans also favored Indian methods of warfare, including concealment and using cover whenever possible. This was especially true of the frontier borderlands. Frontiersmen favored the celebrated Pennsylvania rifle, which in the hands of a good marksman could be accurate up to 200 yards, maybe a little more. When riflemen from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland began to join Washington’s forces in Cambridge, they caused quite a stir.

Riflemen, especially under the command of Daniel “Old Waggoner” Morgan, would contribute to the American cause in the years to come. But rifles were slow to load, easy to foul, and did not take a bayonet. This meant the rifle was a specialist weapon, not one for the whole army. Victory would depend on the smoothbore musket and all that came with it, including mindless drill, massed volleys, and open air fighting with little protection from enemy return fire.

But training was as chaotic as the army camp itself. There were at least three manuals used at the time, and officers used whichever they fancied. Short-term enlistments did not help. In the summer of 1775 many soldiers were due to go home on December 31 of that year. Even if a man did get some training, it was wasted, because most had little inclination to reenlist.

Somehow the Continental Army managed to hang on until independence was declared. Brilliantly improvising, the Americans dragged artillery from Fort Ticonderoga across snowy fields by ox teams. They used these guns to fortify Dorchester Heights just outside Boston. The British soon evacuated the city, along with many Tories.

Soon after the Declaration of Independence, the American cause was hit by a string of near-fatal defeats, redeemed by two small but crucial victories at Trenton and Princeton. The next year British General John Burgoyne and his entire army surrendered at Saratoga, bringing France into the war as an American ally.

American soldiers fought well, especially if circumstances favored them as at Trenton and Saratoga. But they still sorely needed training in the European way of war if they had any hope of consistently beating British regulars. Continentals did not maneuver well, or change from one formation to another with the skill and discipline of the redcoats. They also were deficient in the use of the bayonet, still an important weapon of war in the 18th century.

Who would provide such training? Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, the two American commissioners in France, were actively engaging foreign officers for American service. Unfortunately, the trickle of applicants became a flood, until Deane admitted, “I am well nigh harassed to death with applications of officers to go to America.”

A few were excellent officers, or at least showed great potential. There was, for example, Marquis de Lafayette, a young man with a passion for the American cause and important political connections to boot. But most were mediocre at best. But then, on June 25, 1777, a middle-aged Prussian showed up at Franklin’s door at Passy, a village not far from Paris. He was Baron Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin von Steuben. This was no ordinary old soldier, but a man who had fought in the army of Frederick the Great.

Friedrich von Steuben was born on September 24, 1730, into a family of the Junker social class. Junkers were Prussian aristocrats who were expected to serve the king with wholehearted devotion, usually as soldiers. Steuben’s father, Wilhelm August, was a talented military engineer who was sent by King Fredrick William I to Russia to help Czarina Anna rebuild her army. His family went along, and young Friedrich soon learned how to speak Russian.

Steuben senior returned to Prussia in 1739, and the next year a new king, Frederick II, ascended the throne. Frederick seized Silesia from Austria, setting off a new round of European wars. At 16 Friedrich joined the Infantry Regiment von Lestwitz (Regiment No. 31) at Breslau, Silesia. He was a Freikorporal or officer-cadet, a position that at least on paper was considered something like an noncommissioned officer.

The Prussian system required that young officers be directly responsible for the well-being of their men. Though never too familiar with their charges, young cadets and officers became well acquainted with the daily lives of the men who served under them. A Prussian officer was supposed to be strict but fair, and it was expected that he share in their hardships and dangers. Though discipline could be severe if a soldier broke the rules, real bonds of mutual respect could develop between an officer and his men.

As the 1750s progressed, young Steuben and his regiment remained with the Breslau garrison. Some officers used their free time to drink and carouse, flirt with local girls, or visit prostitutes. Steuben rarely joined in their activities. He loved the theater, read works like Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and studied mathematics. He also had an aptitude for languages and soon mastered French. This was important, because French was the lingua franca of Enlightenment Europe and a language that Frederick the Great himself favored.

Like most soldiers Steuben longed to prove himself in war. He got his chance when the Seven Years War broke out in 1756. Austria, still smarting from the loss of Silesia, formed a large anti-Prussian coalition that included France and Russia. Steuben fought in a number of major battles, including Frederick the Great’s masterpiece, Rossbach. But Steuben was captured by the Russians and sent to St. Petersburg as a prisoner of war.

Steuben remembered the Russian he picked up as a child and could speak directly to his captors. Officers were well treated, and Steuben’s winning personality made him a lot of friends. Perhaps the most notable was Peter Ulrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp and heir to the Russian throne. In 1762 the duke became Czar Peter III and immediately made it known he wanted to make peace with his idol, Frederick the Great.

Steuben immediately informed the Prussian foreign minister, who passed the glad tidings to the king. Frederick was delighted, and before long negotiations took Russia out of the war. France and Austria, their major ally gone, had no choice but to make peace with Prussia. The soldier king and his realm had survived.

Frederick the Great decided he needed fresh blood among the senior officers. To this end he created a rudimentary staff school, the Spezialklasse der Kriegskunst. There would be classes in strategic planning and the art of being a general. The schoolmaster was none other than Frederick the Great himself, considered one of the great commanders of the 18th century.

The school was small and exclusive; only 13 officers were enrolled. After training and perhaps a bit of seasoning, these men would in time become generals in the Prussian Army. Captain von Steuben was one of them. But in 1763, for reasons still not entirely known, he was dismissed from the service. The king was downsizing his army after the war, true, but there was a story that Steuben had fallen afoul of a powerful fellow officer. Perhaps it was General Von Anhalt, who was known to be jealous and vindictive.

In any case, Steuben was cut adrift, his future uncertain. In 1764 he landed a position as court chamberlain to Prince Josef Friedrich Wilhelm, ruler of Hohenzollern-Hechingen. Germany was not yet a nation, but rather a patchwork of some 300 large and small states. Hohenzollern-Hechingen was one of these, a tiny principality that was so quaint it seemed to be from a fairy tale.

Steuben’s duties were light, but he did manage to procure the Order of Fidelity from the Margrave of Baden-Durlach. Something else came with the distinction: the title of Freiheer, or baron. But by 1775 he tired of this picturesque backwater and sought out a military position. Employment in France, Austria, or even Britain was not possible. But then he heard of the American colonists and their struggle for independence.

Encouraged, Steuben went to Paris and eventually sought out the two American commissioners, Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane. Deane was enthusiastic about this now middle-aged Prussian, but Franklin was cool, saying nothing but observing all. After a time Franklin was positively discouraging, refusing to even to pay Steuben’s travel expenses.

Deeply disappointed, Steuben was about to leave Paris when news came that the Margrave of Baden wanted him at Karlsruhe. There was an opening in the Margrave’s army, and the ruler wanted Steuben to fill it. No doubt elated, Steuben left France and was soon in Baden. Unfortunately, when he arrived at Karlsruhe he was shocked to discover the army vacancy, and his whole future in Baden, was in serious jeopardy.

Person or persons unknown had spread the rumor that, while chamberlain at Hechingen, Steuben had taken liberties with youths and young boys at court. In the Prussian Army, homosexuality was tolerated if discreet, but in the rest of Europe it was considered perverted and sinful. The idea that Steuben was taking advantage of youngsters made the charges particularly serious.

Was Steuben a homosexual? Quite possibly, but these charges had all the earmarks of a vicious smear campaign. Almost all of Steuben’s friends abandoned him, and it was clear the stain of pederasty would follow him even if he was declared innocent. Here he was, an aging, unemployed officer with few prospects, a suspected pederast with whom few wanted to associate.

But then salvation arrived in the form of a correspondence. He got a letter asking him to return to Paris at once. It seems the Americans had changed their minds. They wanted him after all. The Continental Army desperately needed expertise in army organization, training, logistics, and planning. Steuben would be a godsend to the struggling Americans. The idea that he was a veteran of Frederick the Great’s almost legendary Prussian Army was another point in his favor.

Though Steuben’s expertise was real, his résumé was deliberately doctored with exaggerations, and in some cases, outright falsehoods. Franklin and Deane were the main authors of this deception, in large part to win the acceptance of Congress. Steuben claimed, for example, that he had been a Prussian lieutenant general, when his real rank had been captain. Since he had no evidence for the exaggerated claims, it was said that he came to Paris so hastily he had left the supporting documents at Karlsruhe.

Steuben left France on Friday, September 26, 1777, aboard the frigate L’Heureux, a warship disguised as a ship-rigged merchantman. The ship’s hold was filled with contraband, including muskets, mortars, cannons, and several hundred barrels of gunpowder. Since all these goods were destined for the American rebels, France had to be circumspect in this operation. The ship’s name was changed to Flamand, and its papers were falsified.

As a retired general about to reenter active service, Steuben was expected to have an entourage of some sort. He was bringing four young aides with him, the most important being Pierre-Etienne Duponceau. Seventeen-year-old Duponceau was a scholarly young man who spoke fluent English. This was important, since the baron did not speak English, except for a few words. One of his favorites was “goddamn.”

Later, when he was in America, Steuben brought two other promising young officers into his military family. One was Alexander Hamilton, who was almost a foster son to George Washington and was later celebrated as the first secretary of the treasury. The other, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, was a brilliant engineer who after the war would play a major role in the planning and design of Washington D.C.

Steuben arrived in America after a somewhat rough passage of almost two months. After some interviews with the Congressional Board of War, Steuben was formally accepted and made captain, which was ironically his real rank under Frederick the Great. With the preliminaries at last behind him, Steuben was told to report to the main Continental Army under Washington. It was February 1778, and Washington’s forces were in winter quarters at Valley Forge.

The baron arrived at Valley Forge on February 24, 1778, and was pleased that Washington personally rode out to meet him. The two exchanged pleasantries, but Steuben was a little disappointed that Washington seemed stiff, formal, and overly dignified. The Prussian had expected a much warmer reception. But General Washington, a reserved man by nature, was also consciously playing the role of leader of the only body, except the Continental Congress, that truly represented a fledgling United States.

Actually Washington liked Steuben, and as the weeks went by showed that he had complete confidence in the middle-aged Prussian. Steuben was given complete freedom to make a thorough inspection of the camp, including its organization and logistics. The baron lost no time in fulfilling what was expected of him. For the next two weeks Steuben conducted extensive tours on horseback, and the tough old soldier must have been appalled at what he saw. “No European army,” he freely admitted, “could have been kept together under such dreadful deprivations.”

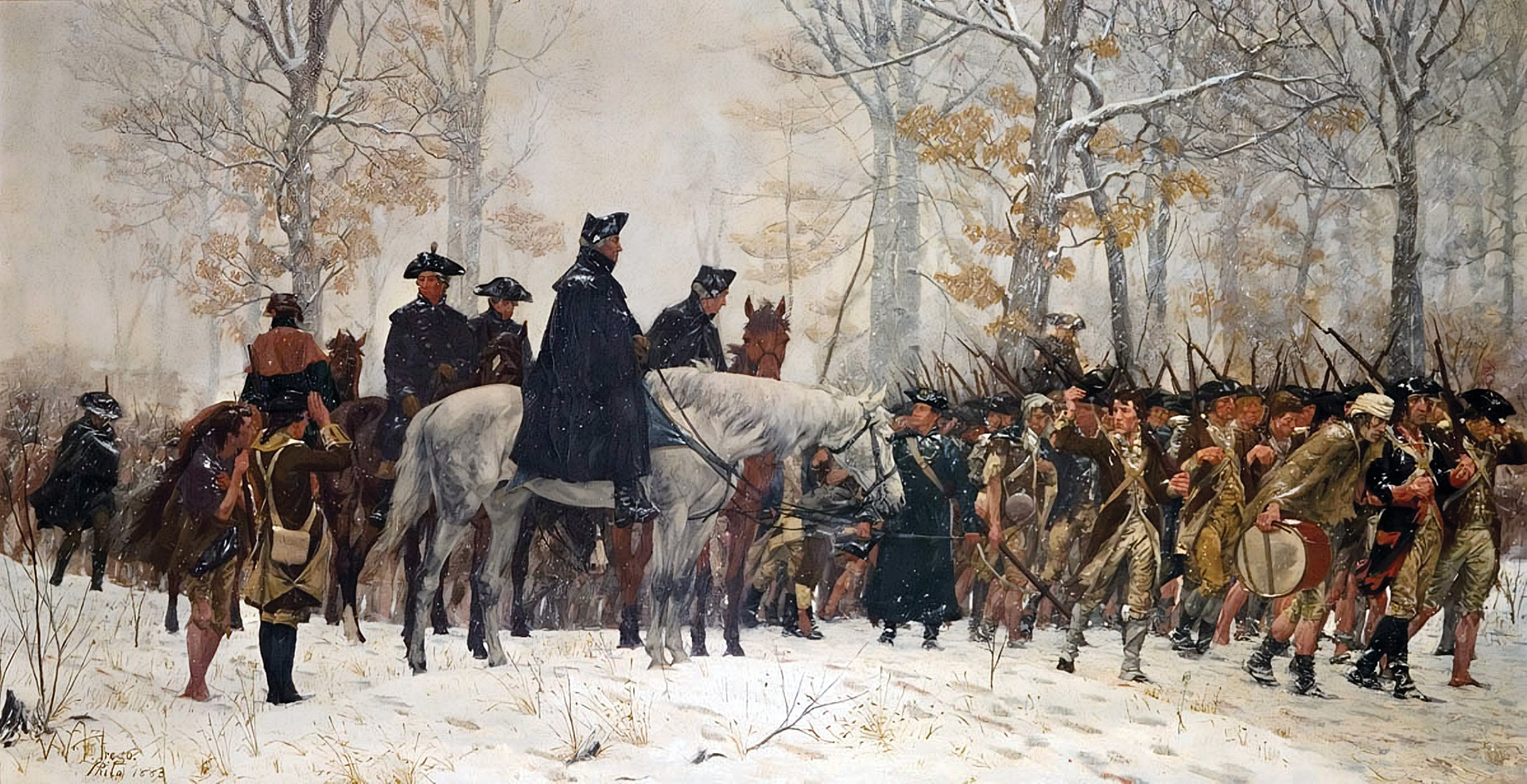

Washington was lodged in a simple but sturdy farmhouse, but most of the army lived in rough log huts occupying about 2,000 acres of land. Today the very name Valley Forge conjures images of ragged soldiers enduring cold, starvation, and sickness with scarcely a murmur. For once, the reality was actually worse than the national saga.

The men had to endure snow and freezing temperatures in uniforms that were nothing more than tattered rags. Some literally had no trousers and had to gird themselves with thin blankets. Many had no shoes, and Washington himself noted that when the barefoot men marched, they left bloody tracks in the snow.

Amazingly, most of these men were not the sturdy farmers of Lexington and Concord, though a core of 2,000 to 3,000, were holdovers from the earlier period. The ranks were filled by indentured servants, poor landless men, recent immigrants, and others lower down on the social scale.

Logistics were also a nightmare. Bad weather hampered the transportation of supplies, and both the quartermaster and commissary departments were marked by widespread mismanagement, incompetence, and outright corruption. Not everyone was corrupt; a small dedicated staff did what they could, but the odds were stacked against them. Starving soldiers subsisted for days on fire cakes made from flour and water.

Steuben poked around the camp for days, making copious notes that would later be transformed into memos to Washington. He would visit the common soldiers in their log hovels, asking them about their health, officers, and daily routine. He really seemed to want to improve their living conditions, which made them respect this foreigner from across the sea.

His appearance also impressed them. He might have been growing a middle-aged paunch, but otherwise he seemed the very embodiment of a professional soldier. Private Ashbel Green, then only 16 years-old, later recalled, “Never before, or since, have I had such an impression of the ancient fabled God of War as when I looked on the baron.”

Washington decided to make Steuben inspector general, a position that included the rank of major general. An inspector general had to make sure an army was well drilled, trained, clothed, and fed. It was his job to discover shortages or other problems and make sure the proper authorities, such as the quartermaster, acted on his recommendations. He also kept a careful record of regimental strengths and held officers responsible for the whereabouts of their charges.

Steuben’s first assigned task was to take over the Continental Army’s training. The goal was for the American troops to be thoroughly competent in European methods of war. The Continental Army also desperately needed some sort of uniformity, that is, a standard to which all could aspire and ultimately master. There were at least three manuals being used at the time, which caused confusion when units were brigaded together.

The baron believed that officers should take an active part in the drill instruction, not just leave it to sergeants as in the British Army. While never overfamiliar, Steuben showed he liked his men and their welfare was one of his primary goals. He also formed bonds with the junior officers, many of whom were just as ragged and half-starved as the rank and file.

To show they were appreciated, Steuben arranged a little party for the impoverished junior officers. He managed to scrape some rations together, together with a few small luxuries, for the feast. They dined on tough beefsteak and potatoes, with hickory nuts for dessert, which they washed down with a fiery liquor called salamander. One of the young officers was James Monroe, future president of the United States.

Steuben’s primary concern was training, and he gave the matter his undivided attention. It was already March 1778, and in a few weeks the spring campaign season would open. Could he train an entire army in time? Steuben solved the problem by forming a model company. There were about 150 men in this company, too unwieldy for effective instruction, so the baron selected a 20-man squad to work with first. They serve as the template that the rest of the company, and eventually the whole army, would follow.

The squad was put through their paces while the rest of the company looked on. They were taught how to dress ranks, stand at attention, march at a rapid pace, and change direction suddenly without breaking formation. The baron was gruff, but humor always managed to seep through the stern façade. If a line was not arrow straight, Steuben would good naturedly lay hands on the offending soldiers and push them into proper position.

Soon the other members of the company would be put through their paces, broken up again into squads for easier handling. The baron’s entourage, well versed in his methods, would each take a squad and drill it until the maneuvers were second nature. As the days passed the model company began to attract attention. Its intricate drills—and above all, the baron himself—became a source of entertainment in an otherwise bleak, cold, and hungry camp.

The baron often flew into a rage when mistakes were made, his face turning an apoplectic red as he peppered the air with a stream of obscenities in French and German. Teufel—devil—was one of the milder oaths. Sometimes the anger was real, but often it was done for effect and to entertain the watching crowds of soldiers. Steuben would also stomp the snowy ground in rage, waving his silver-headed swagger stick.

His audience on the sidelines thought this was hilarious, as when he asked a translator, probably in French, to “come and swear for me in English; these fellows won’t do what I bid them.” But while they were being entertained they were also getting a foretaste of what they too would soon have to master.

Steuben was a success because he grasped the fundamental differences between Americans and Europeans. Americans were much more individualistic. “The genius of the nation,” he once wrote, “is not to be compared with the Prussians, Austrians, or French. You say to a soldier ‘Do this,’ and he does it; but [here] I am obliged to say ‘This is the reason why you ought to do it,’ and then he does it.”

Steuben took his job very seriously, and if he drove the men hard he drove himself harder. After sunset he would work feverishly by candlelight then snatch a few hours sleep before rising again at 3 am. He reviewed the notes he had scribbled out the day before while his manservant Vogel powdered his hair and braided it into a long cue. The extra long queue was a distinctive emblem of the Prussian Army.

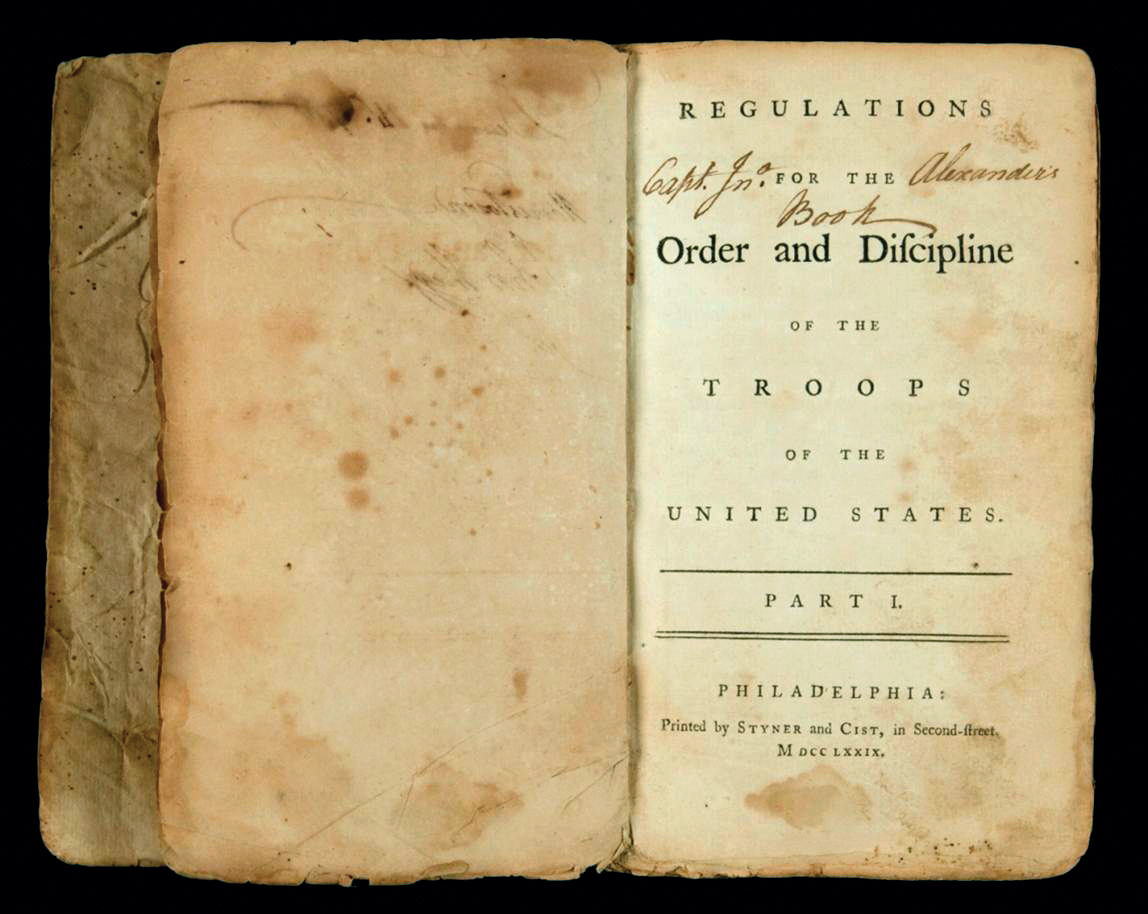

As time went on Steuben improved the sanitation of the army camps. Latrines and kitchens were placed on opposite sides of the camp, and the tents or huts were in orderly rows lining company and regimental streets. But Steuben’s longest lasting achievement was his drill book, a work based on his Valley Forge experiences. It was formally entitled Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, but most people simply called it the Blue Book.

Steuben’s training methods were vindicated on several occasions, but most especially at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778. Though tactically a draw, the Continentals traded volleys with British redcoats toe to toe without flinching. Even in the earlier stages of the battle they showed their mettle. Earlier in the day, when some confusion reigned and they were told to withdraw, they did so without panic and in good order.

The rest of Steuben’s Revolutionary War career had its share of ups and downs. When he was sent south to help in the defense of Virginia, he had serious differences with the state’s governor, Thomas Jefferson. He also fell ill but recovered to participate in the Yorktown campaign that to all intents and purposes ended the war.

Washington wanted to reward Steuben, so he was given command of the one of the American divisions during the siege of Yorktown. It was one of the proudest moments of his life. After the war he became an American citizen and settled on a property near Rome, New York. He was cash poor but did own land in various places. Congress, usually stingy, did finally give him a $2,500 pension that eased some of his money woes.

Though Steuben’s health was failing, his mind was active and he was still interested in military affairs. He urged that the United States create a national military academy, but the fear of military dictatorship was so strong West Point was not established until 1802. Steuben died on Friday, November 28, 1794. His Blue Book would remain the chief training manual for the U.S. Army until the War of 1812.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments