When the skies above Pearl Harbor were stained with the smoke of war on the morning of December 7, 1941, and other U.S. installations in the Pacific were struck by Japanese forces, the American military had been caught unprepared. For several months, the prospects for recovery seemed dim. Nevertheless, soldiers in far-flung outposts held on with grim determination. American industry roared with the production of war materiel. Slowly, the tide began to turn.

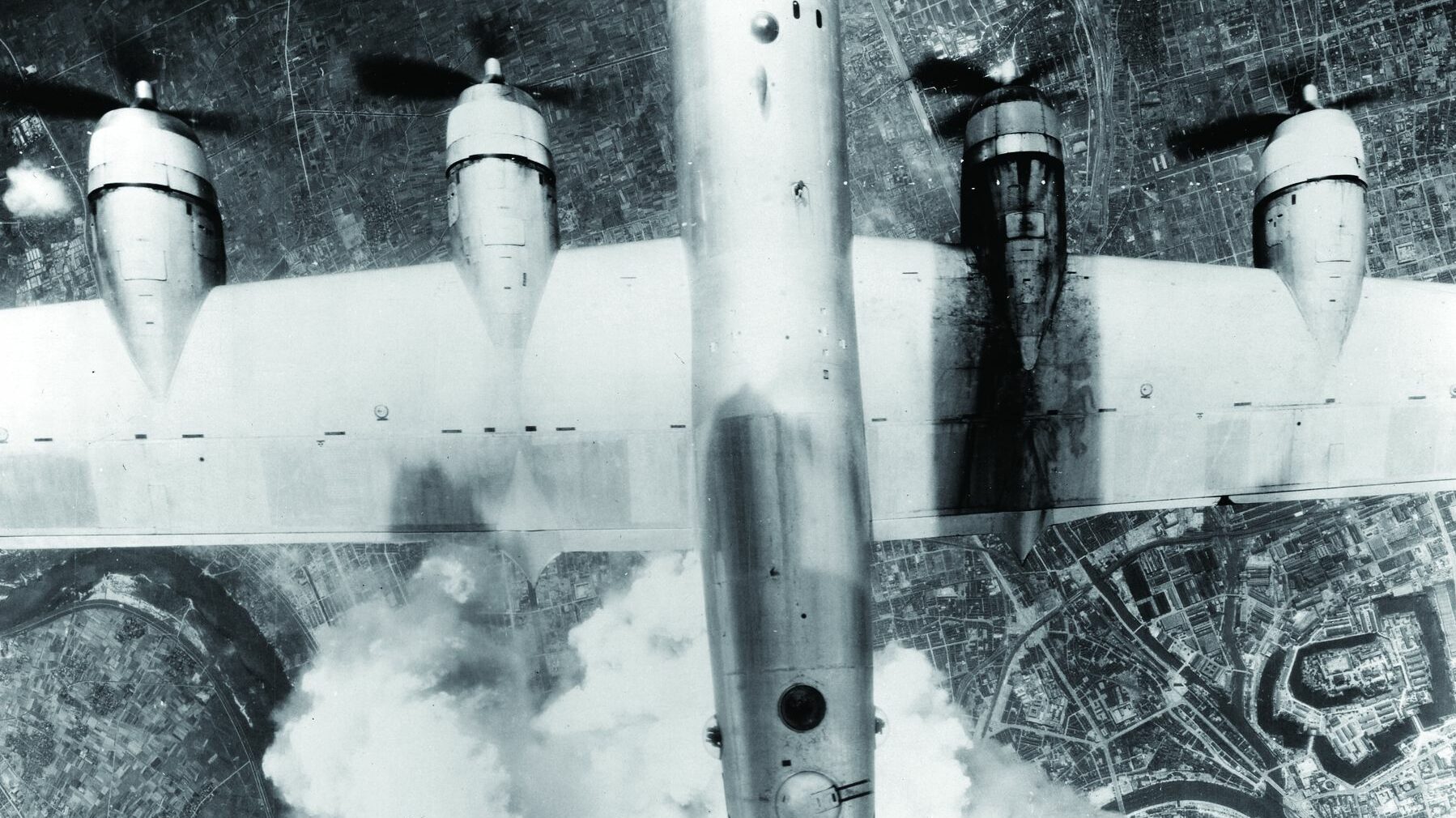

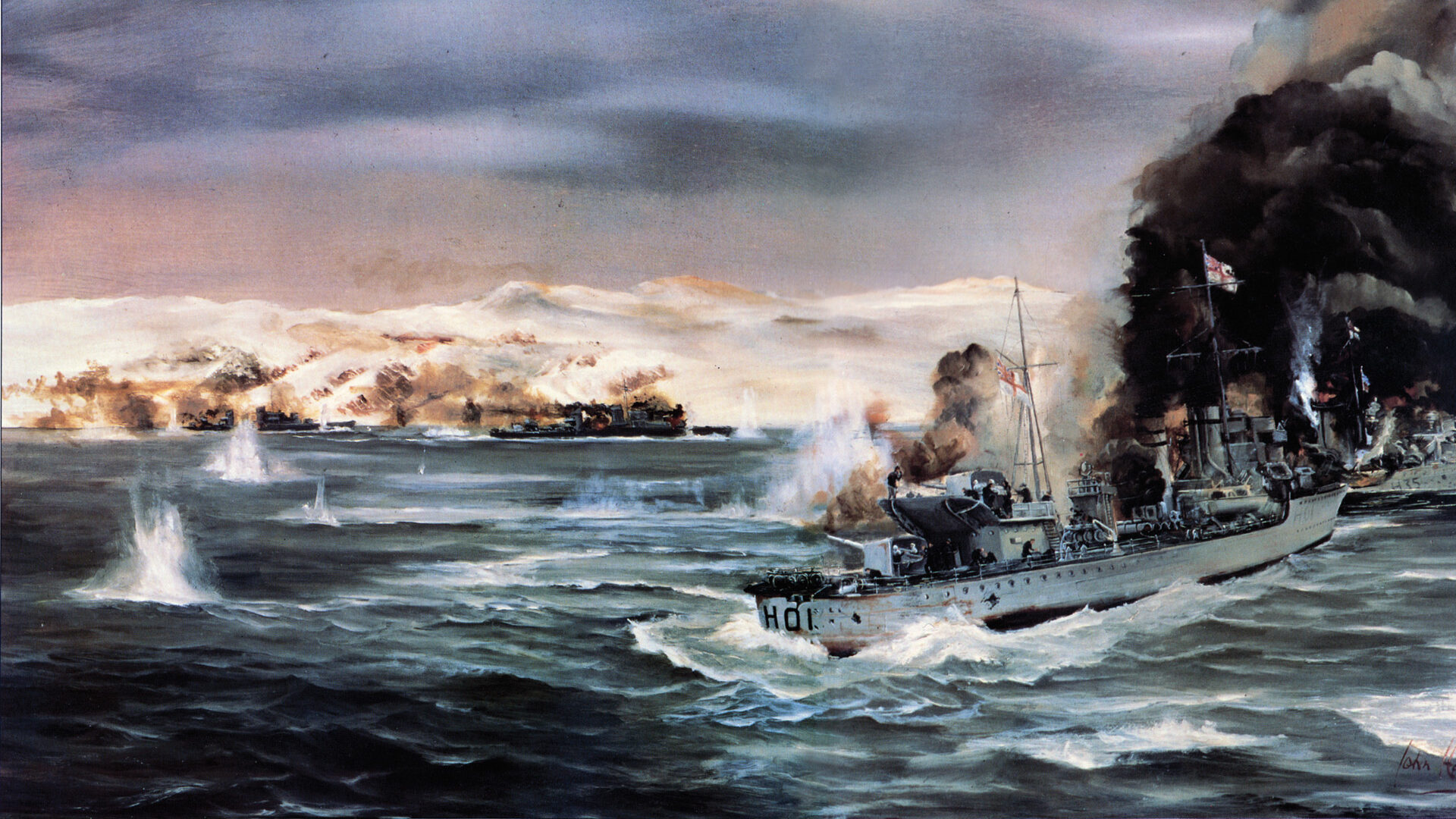

The long road to victory in the Pacific was accomplished by Allied forces through a series of actions on land, sea, and air. A 44-month campaign of island-hopping amphibious assaults liberated some enemy strongholds and bypassed others, moving inexorably toward the Home Islands of Japan. The story of hardship, sacrifice, and determination that took place in the Pacific from 1942 to 1945 is chronicled in tremendous fashion at the National D-Day Museum in New Orleans.

When the museum officially opened in June 2000, it was as an homage to the men of Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy that ultimately led to the liberation of Western Europe and the defeat of Nazi Germany. Fulfilling this original purpose nobly, the museum displays artifacts, interactive centers, films, and photographs of the “Longest Day.” Founded by acclaimed author Stephen Ambrose, it became an instant success.

However, it was apparent that the stories of other “D-days” should also be told. In December 2001, a full 60 years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the museum opened its first expansion, a 5,000-square-foot gallery called The D-Day Invasions in the Pacific. A fitting tribute to the men who participated in amphibious landings during the Pacific War, the exhibits flow chronologically through the epic struggles that took place on islands with strange-sounding names. Few Americans had heard of places such as Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Bougainville, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, or Okinawa before the war. Afterward, these locales would never be forgotten.

While the massive scope of the war in the Pacific is conveyed, the gallery succeeds admirably in portraying the personal nature of the life and death struggles that were involved. A mangled helmet worn by an American serviceman who was killed while wearing it, a Navy Cross awarded to a Marine who was forced to kill an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat, a series of letters written by an Army private who died on New Guinea, and Japanese currency, its edges burned by an American flamethrower, attest to the savagery of the fighting.

A huge map of the Pacific Theater summarizes the war at the gallery entrance, and oral histories, films, animated maps, artifacts, and memorabilia are displayed throughout. Small theaters repetitively show short films on the coming of the war, the Battle of Midway, and the Battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf. From Pearl Harbor to New Guinea and the Philippines and across the Central Pacific to Tokyo Bay, the story of the Pacific D-days is told.

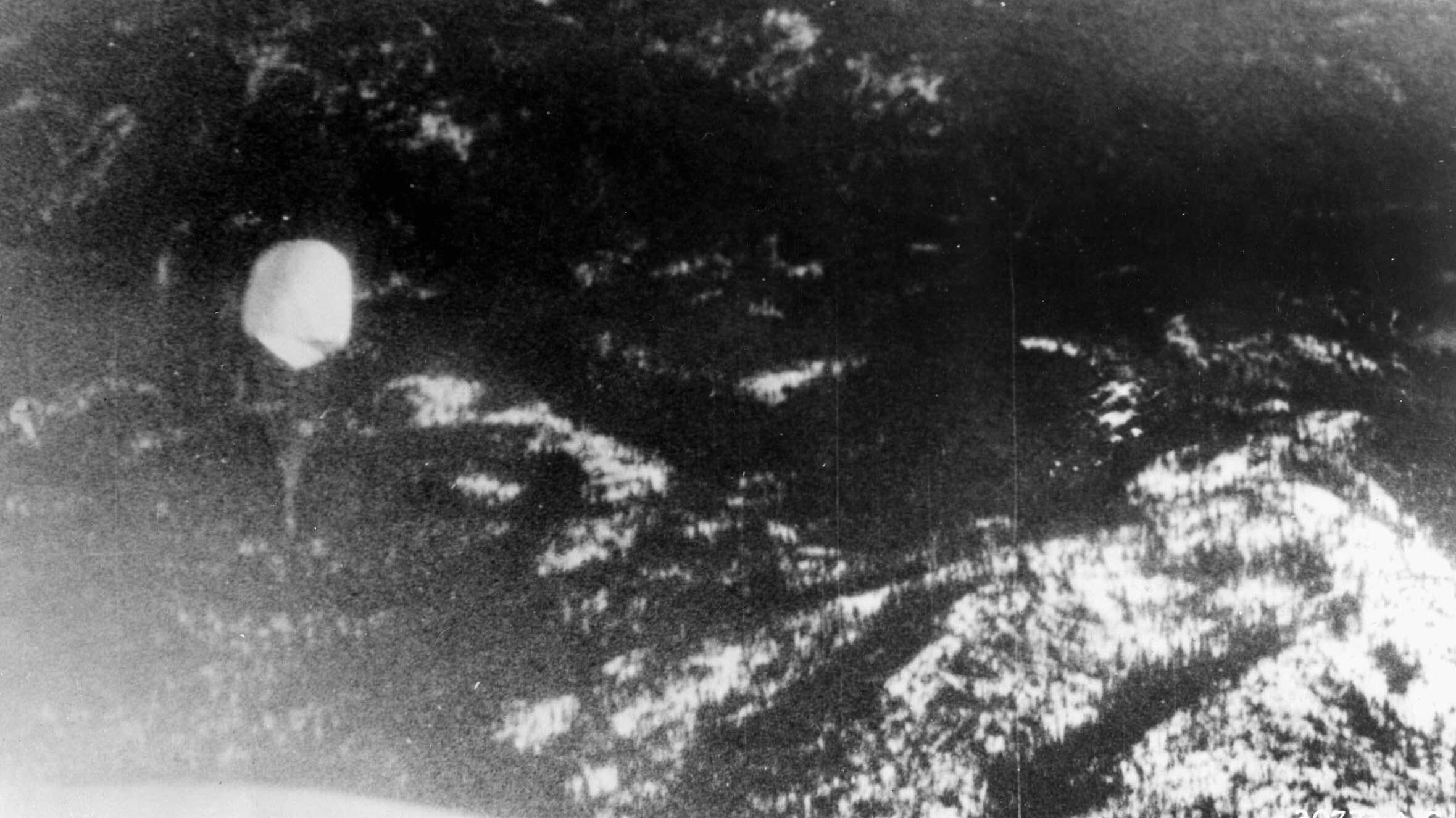

The gallery ends with coverage of the still-controversial dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, followed by a haunting presentation called “Faces in the Pacific.” The documentary Price for Peace, coproduced by Ambrose and Stephen Spielberg, is shown in the Malcolm S. Forbes Theater. The film, which includes reminiscences from both American and Japanese veterans, was directed by Oscar winner James Moll.

The Pacific wing of the National D-Day Museum serves as a long overdue acknowledgement of the heroism and devotion to duty of veterans of jungle, beach, blood, and sand, while only adding to the great achievement of recounting the story of the most famous D-day, June 6, 1944.

Plans are under way to open the Center for the Study of the American Spirit, which will examine the development of the American spirit during the years of World War II.

Special thanks to the New Orleans Convention & Visitors Bureau and the well-appointed Hotel Monteleone, located in the French Quarter, for their logistical support during my recent visit to the Crescent City.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments