By Bob Gordon

The M29 Weasel was a machine conceived by a bizarre British chemist obsessed with ice for a unit that did not exist and a mission that never occurred. While super-secret Operation Ploughshare was scratched, the Weasel went on to lead a long and productive, if unheralded, life.

Designed and manufactured at a feverish pitch even as its raison d’etre disappeared, it went on to find myriad military and civilian applications. Fully tracked and amphibious, it carried a payload and crew approximating that of a jeep. Its outstanding feature was its minimal ground pressure, less than that of a human foot. In snowy regions its crews, riding on its wide, full-length tracks, would race over terrain that would stymie a man wading waist deep in the drifts. In the subsequent decades they were used in swampy, snowy, and difficult terrain by troops across the globe. In 1946 they were deployed, but not employed, by the U.S. Army during an alpine rescue operation in Switzerland. Civilian deployments included ski patrolling, even supporting the 1960 Winter Olympics.

Geoffrey Pyke, an Orthodox Jew, fatherless from the age of five, initially attended Wellington College. Sporting the motto Heroum Filii (“The Children of Heroes”), it was the independent school of choice for military officers’ children. Relentlessly bullied for being neither athletic nor Anglican, Pyke was withdrawn and privately tutored until he entered Pembroke College, Cambridge. With the outbreak of World War I he traveled to Germany, using the cover of a journalist for the Daily Chronicle and the identification of an American sailor, and undertook covert public opinion research for British intelligence. Quickly detected, he was interned near Berlin. Escaping and crossing Germany to neutral Holland, he eventually returned to England and wrote a bestseller about his exploits. Before World War II he developed a larger, similar system of operatives claiming to be British golfers, even persuading the Nazis to host a very public Anglo-German match.

In the interwar years he completed his Ph.D. in chemistry, gained and lost a fortune investing, established the alternative Malting House School in his home, and became increasingly obsessed with ice. Central to his bizarre geostrategy was the “fourth element”: ice. Pyke believed employing ice as a weapon of war could defeat England’s enemies. Through Tory Member of Parliament (MP) Leo Amery he became acquainted with Tory MP and future prime minister Winston Churchill, who became enamored of their shared eccentric, occasionally offensive habits, Pyke’s flamboyant life story, and his often outrageous strategic ideas.

Of the latter, HMS Habakkuk—Pyke’s fantastically improbable, icy answer to the “air gap” over the North Atlantic that deprived convoys of aerial protection mid-ocean—takes the cake. His solution was simple and simply impossible. He proposed dynamiting huge bergs loose from the Arctic pack ice and deploying them mid-Atlantic as floating airfields. More practical minds, noting an iceberg’s propensity to roll over as it melted, quickly nixed the idea. Pyke then invented Pykrete, a frozen composite material of approximately 14 percent sawdust and 86 percent ice by weight, with a slow melting rate that is stronger and tougher than ordinary ice. He proposed that his crystalline aircraft carrier be manufactured of it. While a scale model was built secretly in the Canadian Rockies, the introduction of Coastal Command’s long-range Consolidated Liberator GR.I aircraft (known to the British as the VLR) and the outrageous cost in men, materials, and manufacturing capacity of the 2.2 million-ton frozen vessel combined to scupper the project.

Simultaneously, Pyke developed the concept of a mechanized special operations unit swooping from Europe’s snowy wastes onto essential Axis facilities. He proposed attacks on heavy water plants in Norway, from the snowy peaks of the Carpathian Mountains onto the Ploesti oilfields in Romania, and from the Alps into northern Italy. In March 1942, Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations Executive, made the heavy water plan actionable. Codenamed Operation Ploughshare, its approval initiated a search for mechanized snow machines and the men to operate them.

The men, uniquely both Canadian and American, were required to have “the combined qualities of mountaineer, northwoodsman, and skier” along with “a knowledge of I.C. [internal-combustion] engines, leading to driver mechanics qualifications” to operate and maintain the snow machines. Designated the 1st Special Service Force, they would never strike aboard Weasels nor serve in Norway. However, in Italy they captured impregnable Monte La Difensa astride the Liri Valley and terrified the Germans by aggressively patrolling the Anzio beachhead, leaving calling cards on victims, and ended the war in southern France.

The contract to develop and build the snow machine was promptly assigned to auto manufacturer Studebaker with a team of designers and engineers quickly assembled at its South Bend, Indiana, plant. At the same time, existing snow machines were field tested and assessed on Mount Rainier, near Fort Ellis in Washington. Irascible, opinionated, and intolerable, Pyke proved an obstacle threatening a timeline that foresaw production commencing in only six months and field trials following two months later, in early December 1942.

Pyke was convinced that two Archimedean screws or screw pumps (rotating cylinders with a spiral flange like a wood screw), not tracks, were the only acceptable propulsion system. He was dead wrong. The screw pump system worked poorly on inclines and was useless on bare terrain, roadways, and rocks. The drums’ large diameter necessitated their placement under the body and crew compartment, increasing the height of the vehicle commensurably. Finally, unless the engines were placed in the cylinders, an insurmountable engineering problem in the compressed timeframe, the vehicles were top heavy and prone to tipping. Pyke’s insistence on an Archimedean screw was illogical, ineffective, and, thankfully, an engineering impossibility. Justifiably, the chairman of America’s National Defense Research Committee, Dr. Vannevar Bush, described him as “short on physics, especially short on engineering judgment.” Over Pyke’s vociferous and oft overweening objections, the designers settled on a tracked vehicle.

Originally designated the Cargo Carrier, Light, T-15/M28, it had to meet a series of strict parameters. Primarily, it had to be transportable in the modified bomb bay of an Avro Lancaster heavy bomber to be dropped by parachute and amphibious so it could launch from seaborne transport. Minimum speed on the level was set at 20 miles per hour with an operating radius of 250 miles. Carrying a payload of 4,000 pounds, it was to produce less than one psi (pound per square inch) ground pressure, a fraction of the ground pressure of a human foot; operate on terrain ranging from heavy snow and swamp to roadways and other hard surfaces; and be “silent, free-running, capable of free down-hill run” to facilitate commando-type surprise attacks.

The first issue that had to be addressed was the power plant. In 1938, Studebaker introduced the Champion, an inexpensive, fuel-efficient model designed from a “clean sheet.” The Champion engine was a flathead six with a 164.3-inch displacement weighing only 455 pounds, including transmission. With a bore and stroke of 3.00 x 3.83 inches, its compression ratio was set at 6.25:1, and it generated 70 horsepower. It was equipped with a single-plate standard transmission with a controlled differential and a two-speed planetary driving axle with final drive assemblies and drive sprockets. With integral balance weights and oversized bearings, the need for a weighty vibration damper was eliminated, and with all main and connecting-rod bearings interchangeable steel-back Babbitt-lined types, maintenance in the field was simplified.

Judged adequate for the Weasel, the Champion offered two important advantages considering the hurried schedule. First, the Studebaker factory was already producing it. Second, scavenging warehouses and dealerships would provide parts for the assembly of an additional 2,000 immediately. Both Firestone and Goodrich were enlisted to design and produce the tracks—rubber-coated metal grouser-plates riveted to two endless cable-reinforced rubber belts.

By mid-summer, after only four months, prototypes of the T-15/M28 were ready for field trials on the Michigan-Indiana sand dunes on the Lake Michigan shore. Later in the summer, finding snow for further tests presented a problem. Maj. Gen. Simon B Buckner, commander of the Alaska Defense Command, refused to cooperate: “We are right on the doorstep of a Japanese invasion of the Aleutians and are fully committed in all respects. We cannot give you any assistance.” He helpfully suggested the Chilean Andes, but they were rejected over security concerns. In the end, a snowfield in the Canadian Rockies provided the test track.

Reflecting the harried pace from drafting table to field trials, the T-15/M28 proved woefully inadequate. Its top speed was 15 miles per hour, not 20, and it could only climb an incline of 15 degrees, not 20. Its range was only one third of the 250 miles specified. On the other hand, the T-15/M28 outperformed the existing models examined earlier and, most importantly, easily outran crack 87th Mountain Infantry troops on skis over a three-mile course. While the first attempt at an airdrop from a C-54 Skymaster transport failed when the Weasel overturned and cut the suspension lines, with removable fairings and a shock absorbing platform added it could be airdropped. Thus, the basic design was retained for the T-24, and with significant improvements, emerged as the M29A Weasel.

The most important and fundamental change involved the powertrain. The drive wheel moved from the front of the T-15/M28 to the rear, exchanging places with the idler. This followed moving the engine from the rear of the vehicle to the front, on the right of the driver’s compartment. This significantly shifted weight from the rear to the front, quadrupling climbing ability to 60 degrees in ideal conditions. Moving the engine from the rear also provided room for three folding seats across the back of an enlarged cargo compartment that could now accommodate wireless sets and other bulky equipment. With minor modifications, weapons from machine guns to recoilless rifles were also mounted on Weasels.

At the same time the suspension system was entirely redesigned with the original four bogie pairs being replaced with eight to address a problem with track throwing. Overall, the vehicle weighed less that two tons and exerted a ground pressure of 2.1 psi with the 15-inch track and a mere 1.69 psi with the extended 20-inch track. The M29A was five feet wide, 10 feet long, and a few inches under six feet tall, weighing in at 3,725 pounds. Including crew it could carry a payload of 1,200 pounds. After serial no. 2102 the wider 20-inch track was standardized, and in January 1945, a suspension conversion kit was introduced to update older 15-inch models. The wide track added approximately 300 pounds to the gross weight, while reducing overall ground pressure.

The first 1,002 Weasels to roll off the assembly line were officially designated T-24s. Interestingly, the earliest model had a TNT charge mounted between the engine and the rear deck to facilitate self-destruction if this still ‘secret’ vehicle had to be abandoned to the enemy. Studebaker produced 523 M29As in 1943 and another 2,951 in 1944 for a total production run of 4,476 vehicles.

Still numbered sequentially, the M29C integrated design changes to improve its amphibious performance. These included bow and stern flotation compartments that enhanced freeboard and, conveniently, provided extra storage. The addition of twin rudders greatly improved steering afloat. Together they upped the overall length to almost 16 feet. A capstan was also added to the bow deck to facilitate self-recovery. In 1944 and 1945, a total of 10,647 M29Cs were manufactured for a total production run of 15,123 Weasels.

Three armed factory variants were also produced in limited numbers during World War II. The Type A was armed with a center-mounted 75mm recoilless rifle, and in the Type B the weapon was mounted in the rear. The Type C carried a center-mounted 37mm gun. Additionally, a small number of Weasels were armored and equipped with mine/bomb disposal equipment. In the postwar era, a limited number of Weasels upgunned with a 105mm rifle were produced.

Early model Weasels were first deployed by the First Special Service Force during the unopposed invasion of Kiska in the Aleutian Island chain southwest of Alaska on August 15, 1943. They would go on to serve in theaters of operation across the globe from the South Pacific to northwestern Europe.

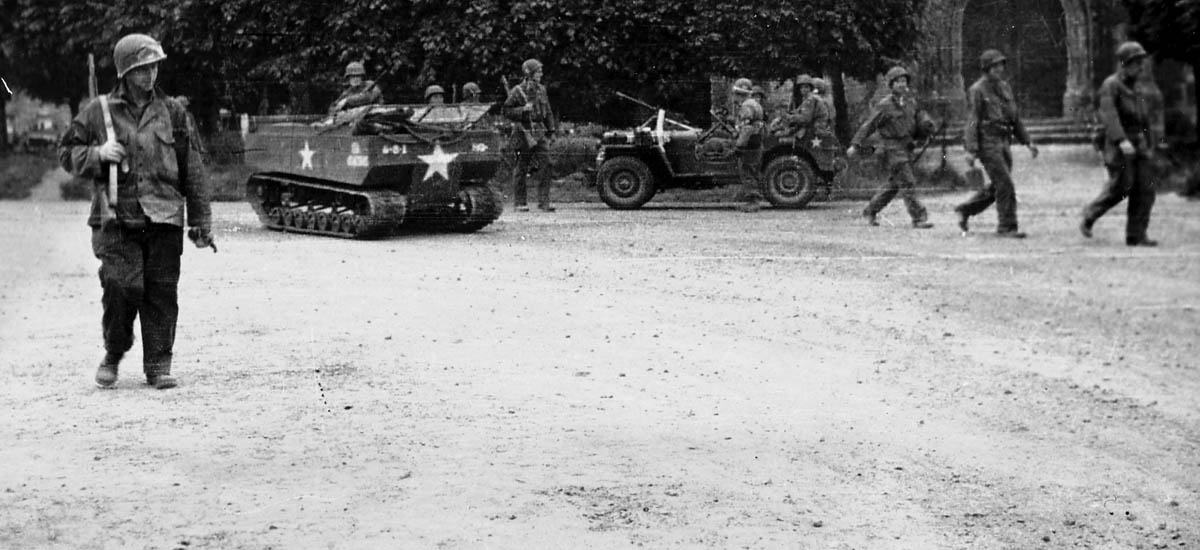

Weasels participated in Operation Huskey, the invasion of Sicily, and went ashore on D-Day. They served the U.S. Army throughout the campaigns in northwestern Europe and Italy. In Normandy they carried ammunition to the front and escorted prisoners to the rear. With the stretcher kit included after serial no. 4104, they were ideally equipped for transporting casualties out of the combat zone. With an RL-31 reel mounted on the rear deck, they were particularly popular for cable laying with Signals units. Designed for installation of antennae on the rear deck, the Weasel was wired to support SCR-506, -508 and -510 radio sets, permitting its use as a command vehicle.

The British 79th Armoured Division, known as “Hobart’s Funnies,” deployed specialized armored vehicles from bridge layers to modified mine-clearing tanks known as “Flails,” and Weasels were included in their repertoire. They proved particularly useful to the Canadian Army in southern Holland in the fall of 1944. The massive Belgian port of Antwerp was captured intact in early September 1944. However, it was of no use until the inundated and heavily defended Scheldt Estuary was cleared, opening Antwerp to the North Sea. The oft flooded and always sodden terrain demanded a series of small-scale amphibious assaults, which required every amphibious animal in the Allied menagerie: Alligators, Buffaloes, Ducks, Terrapins, and, of course, Weasels.

In the Pacific the Marine Corps used them on Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and throughout the theater. A corps report on their deployment on Iwo Jima dated April 25, 1945, concluded, “While not seaworthy, the Weasel proved of inestimable value on land, where it was fast, maneuverable, and could pull trailers and light artillery pieces over terrain untrafficable for wheeled vehicles.” Eventually, the 2nd through 5th Marine Divisions all had Weasels in strength.

In the postwar era, the French used them in their combat operations against the Viet Minh in the deltas of the Red and Mekong Rivers. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the Canadian Army operated Weasels across that country’s high Arctic.

In 1946, a C-53 Skymaster bound for Pisa, Italy, from Vienna crashed on the Gauli glacier in Switzerland. There were no fatalities, but the crew of four and eight passengers, including two senior U.S. Army officers and a child, were stranded. The U.S. Army dispatched Weasels to Interlaken, 15 miles west of the crash site, to affect a ground rescue. However, a successful landing on the glacier by a pair of Swiss Air Force Fieseler Storches, light reconnaissance aircraft, saw the individuals shuttled out by air.

During the 1950s many Weasels were auctioned off as surplus, and they became popular with ski resort operators. This led the organizing committee for the 1960 Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley, California, to request the loan of Weasels from the U.S. Army. Consequently, 25 Weasels provided support throughout the event. Its attendance at the VIII Winter Olympiad may have been the Weasel’s only brush with greatness, but throughout its career it quietly filled a variety of roles for multiple armies in theaters of operation throughout the world, despite the fact the mission that inspired it never was.