By Don Haines

Not all of the 68 infantry divisions available to the U.S. Army during World War II were made up of draftees and enlistees. Some were National Guard divisions composed mostly of men who had signed up during peacetime to be soldiers one evening a week and two weeks every summer. While some were attracted by the opportunity to wear a uniform and still live at home, others had joined for the extra money. One of these outfits was the 29th Infantry Division, also known as the Blue and Gray Division, because most of its members were from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. One youngster from Catonsville, Maryland, not quite 16 years, old decided he wanted to be a soldier. He told the officer who interviewed him that he was 23. The young man’s name was “Lightning” Joe Farinholt, and when a buddy asked him why he did not say he was 18, the age he could enlist on his own, Farinholt said, ”My uncle told me if I ever told a lie, make it a big one. So I did.”

Farinholt Becomes a “29er” At Age 19

The 29th Division was mobilized in March 1941. At the age of 19, Farinholt became a full-time soldier at Fort Meade, Maryland. Farinholt and his buddies had been told they would be on active duty for 12 months. Then came December 7, 1941, and 12 months became “for the duration.”

Farinholt’s regiment, the 175th, along with the other 29ers, as they had come to be called, left Fort Meade in April 1942. There were stops in Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida before orders arrived on September 6 directing the division to prepare for overseas deployment. When troop trains headed north, Joe knew he was headed for the European Theater. On September 27, 1942, the passenger liner Queen Mary, now converted into a troopship, sailed for Great Britain.

In November 1942, the 29th Division moved into Tidworth Barracks, England, replacing the famed 1st Infantry Division, which was leaving for the invasion of North Africa. At Tidworth the 29ers began 20 months of grueling training. Farinholt relished the tough schedule.

As time went on the 29ers began to wonder just what part they might play in the war. They watched other outfits leave for North Africa and the Italian campaign. They knew that other units were being shipped directly from the States to fight in Italy. No one below the rank of colonel, however, knew that the Army had special plans for the 29th Division—participation in the Allied invasion of Western Europe in 1944.

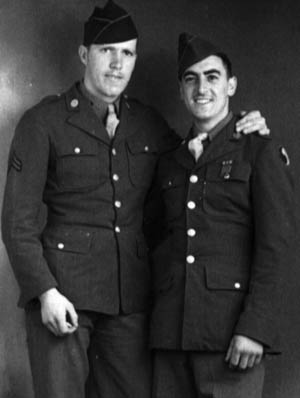

Sergeant Joe Farinholt, who was now commanding an antitank platoon in the 3rd Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment, knew none of this. He knew only that it was his responsibility to keep himself and the 32 men under his command razor sharp. By the spring of 1944, another 17 divisions had joined the 29th in England in preparation for Operation Overlord, the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944.

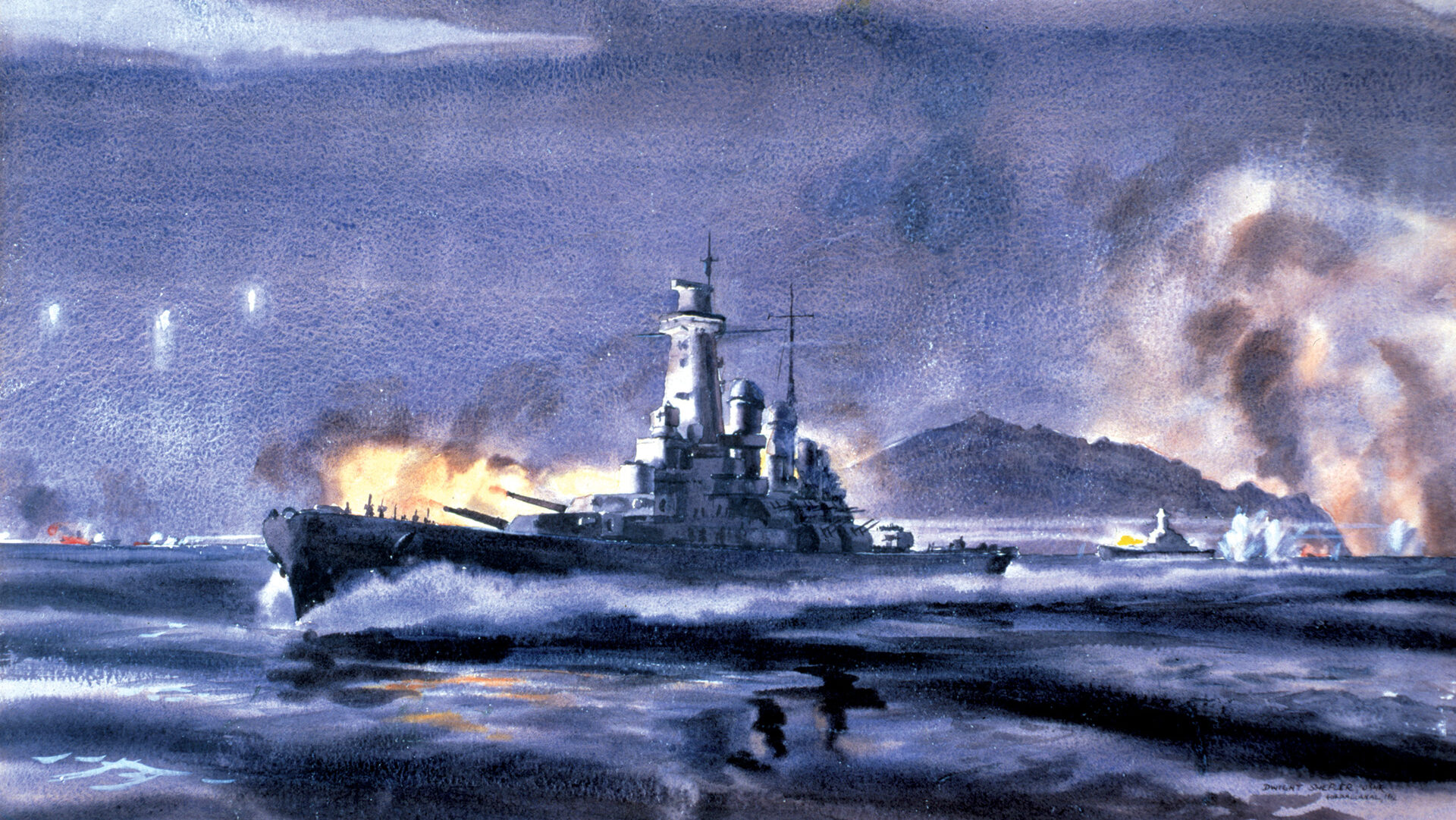

The 29th Division trained for the amphibious landing that was to come. Unlike other elements of the 29th Infantry Division, the 175th Regiment did not land in the first wave on Omaha Beach. It was the evening of June 7 before Farinholt was on his landing craft and headed for the beach. He says he had no feeling about all the destruction he saw on Omaha Beach. He was numb to any feeling as his training took over. No doubt it was Joe’s ability to concentrate on the job at hand that enabled him to compile the brilliant record that followed.

How Joseph A. Farinholt Became Known as “Lightning Joe”

Joe Farinholt and his comrades were given the difficult task of taking the town of Isigny, nine miles inland from Omaha Beach. They expected resistance all the way. Instead, resistance was light except at the village of La Cambre, where a misdirected British air attack inflicted some casualties.

By the time the 175th got to Isigny, the town had been pounded by Allied aircraft and was taken without much of a fight. However, there was plenty of fighting ahead for the 29th Division. Farinholt’s platoon deployed 57mm antitank guns and began to develop a reputation for toughness in combat. For his proficiency in destroying German tanks, Farinholt was given the nickname “Lightning Joe” by his company commander.

The drive to the town of Saint Lo, one of the last German strongholds in France, was costly. It was on the Bayeux highway several miles outside the city that Lightning Joe Farinholt earned his first Silver Star on July 13, 1944.

“I spotted a German mortar position, so I picked up a bazooka and ran forward to knock it out,” he said. “The Germans I didn’t kill ran away. Then I looked up and this German tank was headed right for me. I jumped into the brush, reloaded the bazooka, and knocked out the tank as it went by.”

Young Joe, just four days short of his 22nd birthday, scurried back to his lines, landing on his posterior. An officer picked him up and said, “Son, you’ve just won a Silver Star.”

On 18 July, when Saint Lo was about to fall, Lightning Joe won his second Silver Star. He remembered, “Our position was overrun after a counterattack, and we had to leave our equipment or be taken prisoner. After dark, we ran back and hooked two of our guns to trucks while under heavy fire. We couldn’t get a truck to our third gun, so we pulled it out by hand. We really baffled the Germans with that move because they thought they had us cornered. The next morning we stopped a column of tanks with those guns. That was my second Silver Star.”

By the time Joe had won his second Silver Star, there were only a few of the original National Guard soldiers left in the ranks. Two thousand men of the 29th Division had died in the 43 days it took to go from Omaha Beach to Saint Lo. A ceremony ended with “Taps” and the “Star Spangled Banner” followed by the 29ers yelling in Unison their motto: “Twentynine, Let’s Go!” Farinholt yelled right along with the rest, but he also thought of those who were lost.

Farinholt knew better than to get close to his men. “I had no control over the replacements I got,” he related. “Some men were very green and didn’t last long. I got a call on my radio one day. One of my guys said I better hurry to him because he was thinking about shooting himself. By the time I got there he’d shot himself in the leg. I carried him to the aid station and told him to keep his mouth shut about what happened. That was the only time one of my men cracked. I have no shame in what I did. That boy was a good soldier, but he was only 16.”

On October 13, 1944, Joe was awarded his third Silver Star west of Geilenkirchen, Germany. The citation describes his heroism:

“T/Sgt Joseph A. Farinholt 20343338 175th Infantry, U.S. Army For Gallantry in Action against The Enemy In Germany, on 13 October 1944, During A Period Of Heavy and Constant Enemy Shelling, Casualties Were Sustained In the First BN, 175th Infantry. Amidst This Intense Barrage of Fire, T/SGT Farinholt Left His Sheltered Position and Went To The Aid Of the Wounded Where He Administered First Aid Treatment and Personally Evacuated Four Casualties To a Place of Safety. The Outstanding Courage and Unselfish Devotion to Duty Displayed by T/Sgt Farinholt While Under Heavy Fire, Reflect Great Credit Upon Himself and the Military Service. Entered Military Service From Maryland.”

In his personal account of the incident, Joe Farinholt gives credit to the men who went with him. “My men never ceased to amaze me. They’d do anything for their fellow GIs.”

During the battle for Bourheim, Farinholt won his fourth Silver Star. However, the one medal he did not want was a Purple Heart. That was about to change.

Joe’s fourth Silver Star citation describes what happened:

“T/Sgt Joseph A. Farinholt 20343338, 175th Infantry U.S. Army For Gallantry In Action Against the Enemy In Germany. On 26 November, 1944 While the Third Battalion 175th Infantry Was Defending the Town of ***** Enemy Infantry Supported By Tanks Entered the Town and Advanced Against the Battalion’s Thinly Held Line. Realizing the Gravity of the Situation, T/Sgt Farinholt Ordered His Antitank Platoon to Remain In Position Where They Delivered Such Devastating Fire Upon the Enemy That They Were Forced to Divert Their Attack to Another Sector of the Town. Then finding All Communications Severed By Enemy Artillery Fire, T/Sgt Farinholt Despite Suffering a Broken leg, Asked to be Placed in a Vehicle While He Drove Under Fire To the Command Post to Inform the Staff of the Situation. Such Courageous Actions Reflect Great Credit Upon Himself and the Military Service. Entered Military Service From Maryland.”

What the citation did not say was that Joe had suffered life-threatening wounds. “We were doing a good job of keeping the German tanks at a safe distance until the gun nearest our command post was hit and the gunner was killed,” he remembered. “I ran to the gunner to replace the gunner position, and we were able to knock the tread off a Tiger tank, but the tank was still firing. The rest of the crew ducked for cover, but I was stupid enough to stay put while the tank sprayed our position.

The armor-piercing rounds cut through the protective shield of the gun, and I was hit with shrapnel. I didn’t know how bad I was hit until I tried to walk and saw my leg hanging by skin. I crawled to my jeep and made my way to our command post to let them know what was happening. I couldn’t use the brake on the jeep, so I just crashed into a wall. When I looked at my leg I got scared, but somebody said I had a million dollar wound.”

Doctors wanted to amputate Joe’s leg.

“I told them they couldn’t do that because I would need it later,” he smiled. A general happened to be on the scene and ordered the battalion surgeon to try to save Joe’s leg. The leg was saved, but it never completely healed. Farinholt had to wrap it in bandages twice a day for the rest of his life. He also had 20 pieces of shrapnel in his body. The last two pieces did not work their way out until 1986.

Transitioning to Civilian Life

Joe might have had a million dollar wound but it would be 1946 before he could leave the hospital and return home. By that time the war had been over for a year, and the rest of the 29ers who had survived the war were back in the States. Only 10 percent of those who landed on D-Day had not become casualties.

In retrospect, however, perhaps “Lightning” Joe Farinholt had actually been luckier than most. His time in the hospital actually brought him the best luck he would ever have. Her name was Agnes Marshall, a stunning redhead, whom Joe had met when she accompanied a friend to the hospital to visit her husband, who just happened to be Joe’s buddy. When Agnes left, Joe bet his buddy $10 he would marry this absolute knockout. Joe won the bet. He and “Reds” were married on May 19, 1946, and the union would last 56 years.

By the time Joe and Agnes had come home and settled in the small town of Finksburg in Carroll County, Maryland, the victory fever of 1945 had abated and most GIs had settled into civilian life. No brass bands greeted the man who had set a record for being awarded Silver Stars. Joe and Reds set about living their lives and raising a family. Sometimes people would ask Joe what he did in the war and he would reply that he had received four Silver Stars.

Few people seemed that impressed. Only Joe’s buddies at the American Legion recognized the greatness of his combat record, and for many years that was good enough for Joe. Besides, he and Agnes soon had four kids and there was a living to be made. Those Silver Stars did not put any bread on the table.

It was not until 1994 and the 50th anniversary of D-Day that people began to ask questions and Carroll County residents learned that they had a genuine hero in their midst. The accolades for Lightning Joe began to pour in and have never stopped. He became arguably Carroll County’s most beloved senior citizen, gaining a place of honor in Memorial Day and Veterans Day parades, sometimes riding in a jeep or a restored 1942 Desoto. He could not march in the parades because of his leg injury, but there were photos aplenty of Joe standing ramrod straight and saluting Old Glory while wearing his American Legion cap that bore the 29th Division logo. He always had a Silver Star pinned to his shirt.

Gradually, stories began to emerge about Carroll County’s most famous soldier, and folks began to believe that Joe Farinholt deserved even more honors. They learned how Joe’s lieutenant had recommended him for a battlefield commission after he had won his third Silver Star but the record had gotten lost in the military bureaucracy. Joe had assumed the commission would come through even though his military career had ended after his fourth Silver Star. The commission never arrived, and Joe did not know he could pursue it after so much time had passed. Someone else did. Shortly after the effort to secure the commission was undertaken, Lightning Joe Farinholt attended his granddaughter’s wedding wearing lieutenant’s bars. Joe laughed off the issue of back pay, saying the bars were enough.

The U.S. Navy admiral who awarded Joe his fourth Silver Star decades earlier had been so impressed with his magnificent combat record he suggested that Joe trade his four Silver Stars for one Medal of Honor. Joe declined. “Thanks, but I’ll just keep these.” On that day Joe was a severely wounded soldier, thinking mainly of getting well and getting home. Another medal did not seem that important. Years later, a campaign to get Joe the Medal of Honor was ultimately unsuccessful.

In 1997, the 29th Division was deployed in Bosnia. It was the first time since World War II that the 29ers had deployed overseas. Joe welcomed the opportunity to visit the young soldiers. Those who made the trip marveled at how the old soldier became an instant hit with the modern 29ers. They crowded around him, clasping his hand and asking that he tell the story of his four Silver Stars. He glowed with appreciation as he patiently talked of his exploits on those long ago battlefields.

In June 2002, Joe Farinholt was approaching his 80th birthday. He suddenly became ill and died a short time later. After his death, Agnes worried that Joe might be forgotten. The worry was needless. Joe Farinholt will live forever in the hearts of Carroll Countians.

Originally Published December 30, 2015

Another Blue & Gray hero remembered.

Having fought in the Vietnam conflict with the 1st Cav Division in AnKhe VN 1965-1966 Rifle Platoon Leader. This story captivated me with how he could disregard the enemy fire and continue the action pretty much on his own. It is true he should have received a medal of Honor. The last sentence is a question; who are the hearts of Carroll Countians? Bill

Those who live in Carroll County I’d guess ? . Hope you’re being looked after for your service in the 1st Cav & get to spend the rest of your time in peace & plenty .

The greatest generation for sure

A great read

An outstanding soldier of the 29th, so sorry the wokes are trying to retire your historic Divisional Blue/Gray Patch.

lest we forget

What a great American and what a great story. Regarding the entry: “… she accompanied a friend to the hospital to visit her husband, who just happened to be Joe’s buddy. …” I had friends who were introduced in nearly the exact same way in the late ’40’s, I believe. He was instructing in B-25’s when a nose wheel somehow encountered something like a trench. He was ejected through the roof and spent a year in a coma. Having been shipped home, his best friend started visiting. He brought along his girl friend and she, her best friend. After a time only the best friend kept coming back. She was there when he awoke and a long, successful marriage followed.

My brother Paul was a proud member of the 29th. Drafted right out of high school in 1943, he saw combat in the ETO. Not all members of the division were from MD, VA and PA. Paul was from Western NY.