When athletes become pawns of politicians, their skills being touted as proof of their country’s ideological superiority over others, seldom are events played out as the demagogues would have scripted.

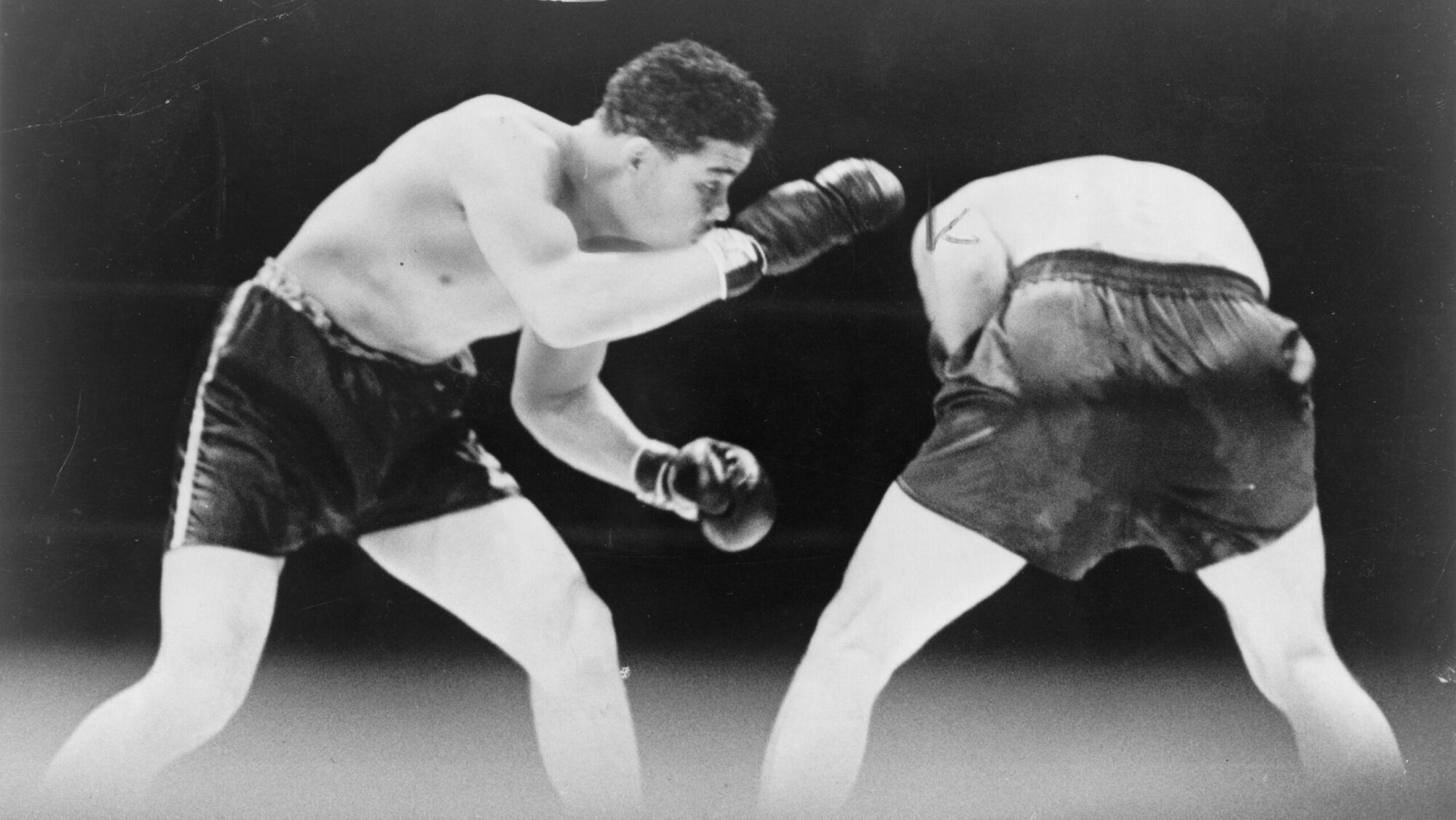

During the Nazi era in Germany, two such events struck blows to Aryan pride and created lasting moments in history. During the 1936 summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Jesse Owens, a black American, shattered the notion that Hitler and his henchmen held of the invincibility of German athletes. Two years later, Joe Louis, another black American and future heavyweight boxing champion of the world, knocked out Germany’s Max Schmeling, who had briefly held the heavyweight crown himself, in the first round of their title fight in New York’s Yankee Stadium.

The June 22, 1938, clash of these boxing titans was actually a rematch. Schmeling had shocked the world and made Germany’s Nazi propagandists euphoric on June 19, 1936, when he knocked out Louis in the 12th round. After his victory, Schmeling became a national hero. He was flown back to Germany aboard the famous airship Hindenburg and received by an adoring crowd. Louis became heavyweight champion in 1937, with only a single loss in his first 69 fights, but stated matter of factly that he would not consider his crown legitimate until he defeated Max Schmeling.

Seventy thousand spectators crowded Yankee Stadium to witness what had been billed as the fight of the century. However, it only lasted just over two minutes. Louis pummeled Schmeling mercilessly, so badly battering the German that he spent a week in a New York hospital.

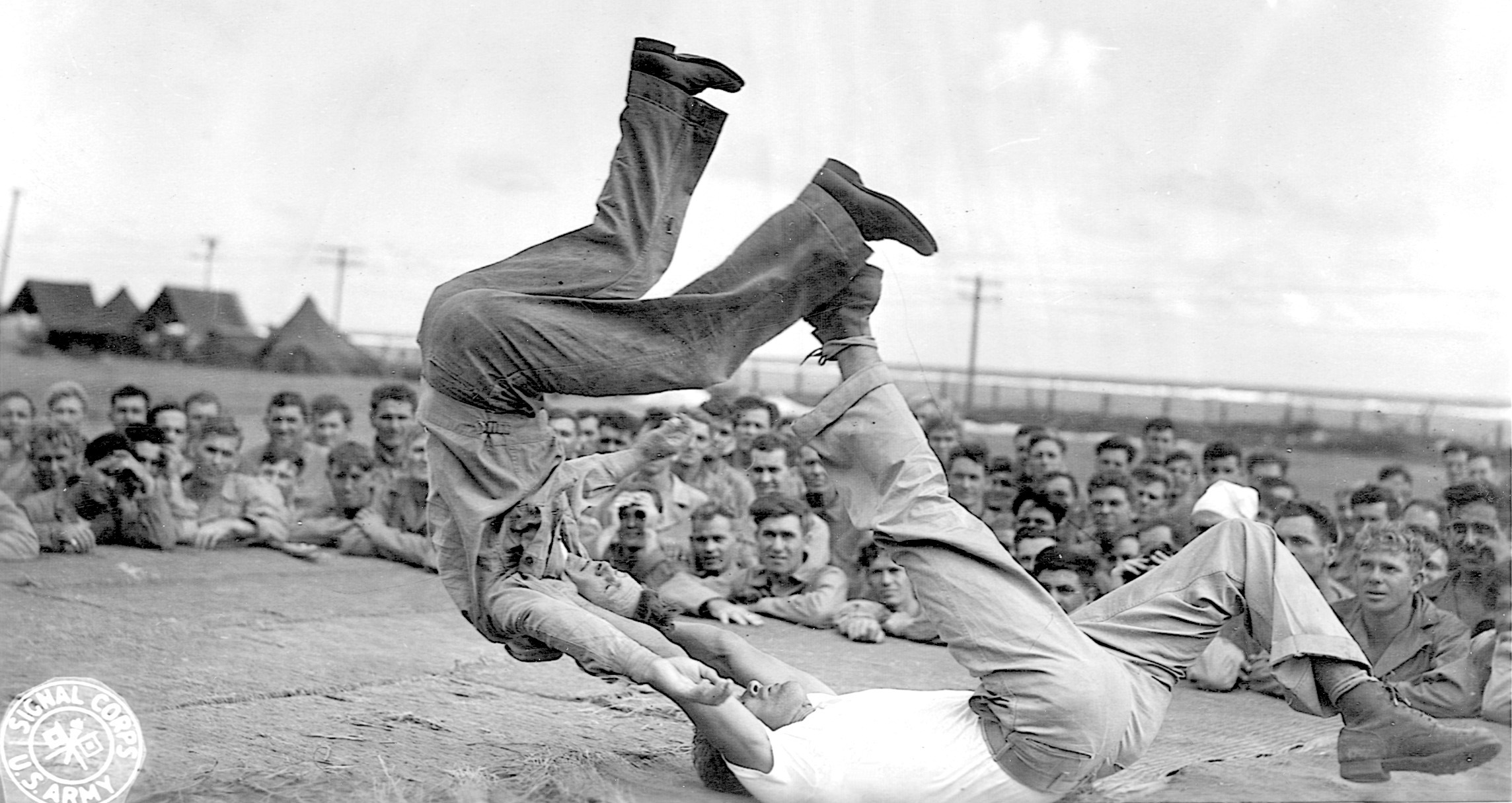

After his loss, Schmeling fell out of favor with Hitler. The boxer was drafted into the German army and served with airborne troops during the invasion of Crete. Disease kept him from fully participating in the campaign, but the German propaganda machine was in full swing and embellished his experience. He was dubiously awarded the Knight’s Cross for bravery in combat.

Those who know of Schmeling only superficially might conclude that he supported the Nazi regime. On the contrary, he never joined the Nazi party to Hitler’s chagrin. He steadfastly refused to participate in the exploitation of his accomplishments by Nazi propagandists. During the 1936 Olympics, he had made Hitler swear that American athletes would be protected. During the horrific Kristallnacht, he hid the two sons of a Jewish friend, David Lewin, from the Nazis in his room at Berlin’s Excelsior Hotel. Throughout the 1930s, he continued to employ his manager, Joe Jacobs, a Jewish American. He never turned his back on Jewish friends or disassociated himself with them.

Schmeling, who died in February at the age of 99, reflected on his life during a 1993 interview, commenting, “I don’t want anyone to say I was a good athlete, but worth nothing as a human being. I couldn’t bear that.”

After the war, Schmeling fought several more times but never regained the stature he had enjoyed in earlier years. A friend who had once served on the New York state boxing commission offered him a franchise to bottle Coca-Cola in Germany, and he became a wealthy man, establishing a foundation which helped many needy people. In 1954, Schmeling and Joe Louis renewed an old friendship. Their mutual admiration for one another would last their remaining lives. When Louis fell on hard times, Schmeling gave him money. He also paid the funeral expenses for Louis, who died in 1981.

During an interview decades after his famous second fight with Louis, Schmeling remarked, “Looking back, I’m almost happy I lost that fight. Just imagine if I would have come back to Germany with a victory. I had nothing to do with the Nazis, but they would have given me a medal. After the war, I might have been considered a war criminal.”

During his lifetime, Max Schmeling proved himself worthy of respect and honor, not simply as an athlete, but as a man.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments