By Al Hemingway

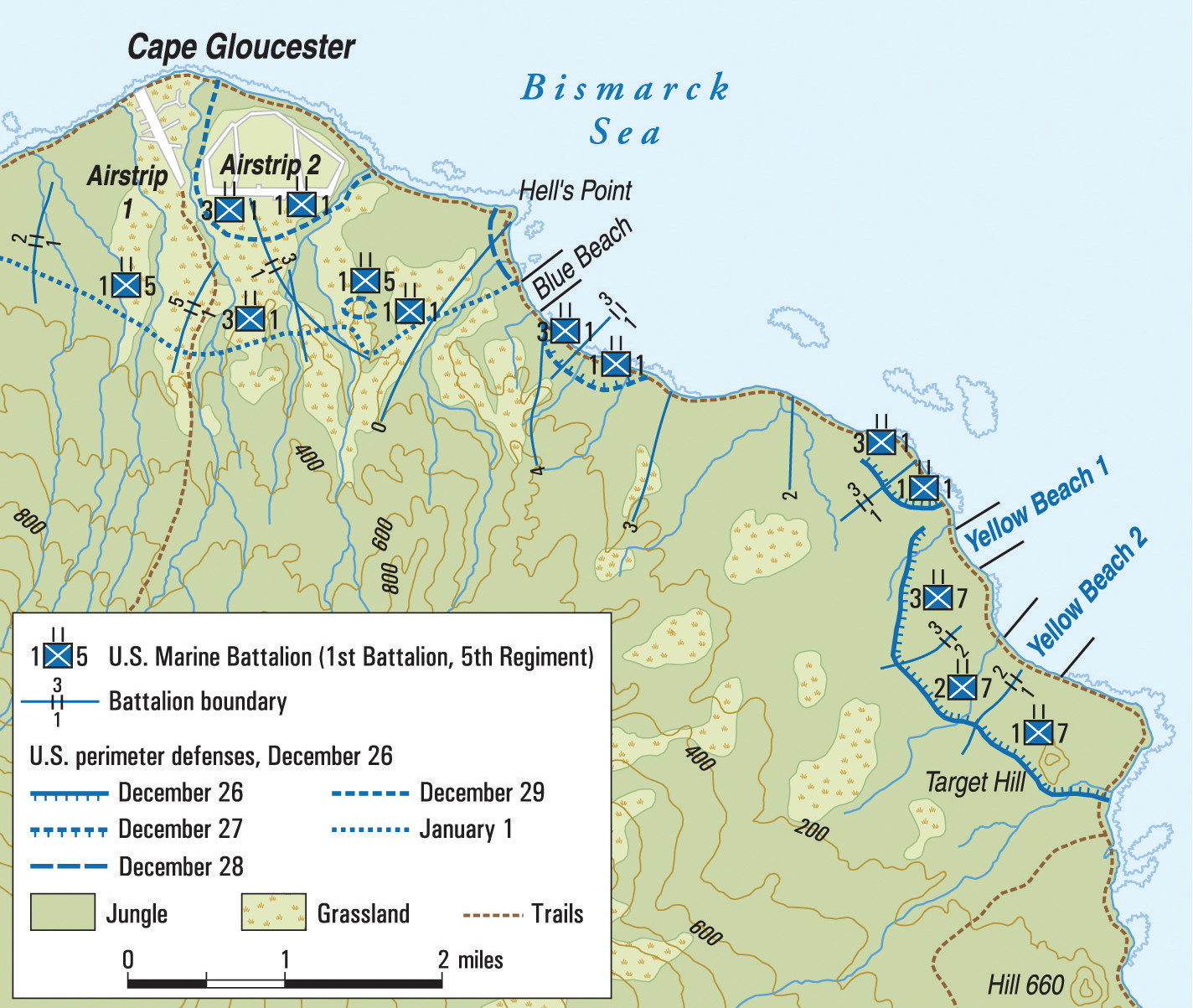

As dawn broke on December 26, 1943, the unmistakable silhouettes of American warships could be easily seen by the Japanese defenders on New Britain Island. Likewise, the combat-laden infantrymen of the 1st Marine Division could make out the outline of Mount Talawe, a towering mile-high mountain that was located on the northwestern end of the island in a region known as Cape Gloucester, the main target of the U.S. invasion force.

For 90 minutes, U.S. and Australian destroyers pounded suspected Japanese positions. Because of the thick jungle, it was impossible to see if the naval bombardment had any positive effect. Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) rocket ships let loose a fusillade to further harass the enemy.

Soon after, U.S. Army Air Corps B-24 Liberator and B-25 Mitchell bombers roared overhead and swooped down on the area, dropping 500-pound bombs on selected targets. At least one bomb scored a hit as a huge fiery mushroom cloud billowed skyward after an enemy fuel dump was struck. When the heavier bombers had completed their work, Douglas A-20 Havoc aircraft flew in to strafe additional targets.

By 7:45 am, Colonel Julian N. Frisbee’s 7th Marines were the first to head to shore. His battalions hit Yellow Beach 1 and 2 against no opposition from the Japanese—but plenty from the viscid undergrowth that was situated at the water’s edge. About 30 minutes later, the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines arrived on the right flank. Their mission was to disembark and move westward along a coastal road and capture the airfield. The 1st Marine Division was about to begin its second major amphibious operation of World War II—but this time under the command of the inimitable General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Southwest Pacific Area.

The New Britain campaign was the first combat operation since the division returned from Guadalcanal in early 1943 after six months of bitter jungle fighting. While the Marines recuperated in Melbourne, Australia, the high command was busy planning its next move against the Japanese.

MacArthur was in the midst of retaking New Guinea from the Japanese. His staff had devised a multiphased plan dubbed Operation Cartwheel. The first objective was Chronicle, the occupation of Kirwina and Woodlark Islands. Next was Postern, which would seize Lae, Salamaua, Finschhafen, and the Madang area, in New Guinea. Last was Dexterity, which called for the occupation of western New Britain.

Since the 1st Marine Division was in Australia, it fell under MacArthur’s jurisdiction. The egotistical officer was extremely pleased and often referred to the unit as “my Marines.” He urgently needed a highly trained unit to capture the all-important airstrip at Cape Gloucester on New Britain and protect his flank from enemy air strikes that emanated from there. The operations collectively were code-named Backhander.

In addition to their role in the Gloucester campaign, MacArthur had bigger ideas for his Marines. He wanted to stage an amphibious assault against the enemy fortress at Rabaul. Situated on the northeast point of New Britain, the sprawling base was the hub for resupplying Japanese units in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. It was also utilized as a naval base. The enemy had landed there in January 1942 and had quickly transformed the once sleepy community into a huge installation that boasted airfields and barracks with more than 100,000 defenders.

Since leaving the Philippines, MacArthur had eyed Rabaul as one of the main objectives that stood in the way of his triumphant return to the Philippines. He opted to pummel the stronghold from the air. While this was transpiring, he attacked eastern New Guinea and the Solomon Islands to move closer to the base.

By October 1943, however, plans to assault Rabaul were scrapped. Military strategists were keenly aware that attacking such a well-defended position would be costly in terms of time and, more importantly, human lives.

While devising the upcoming operation to seize Cape Gloucester, MacArthur’s planners had split the Marine units, something that the irascible Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, commanding the 1st Marine Division, had vehemently opposed. Also, the U.S. Army’s 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment was scheduled to be dropped thousands of yards inland to link up with the advancing leathernecks. “Jungle-conscious” Marine Guadalcanal veterans contested this maneuver. The movements of these widely dispersed forces, they believed, would prove extremely difficult in such rugged terrain.

On December 14, MacArthur and Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, Sixth Army commander, visited the 1st Marine Division command post to discuss the operation. After a briefing by Division Operations Officer Colonel Edwin Pollock, MacArthur asked if they approved of the plan.

Pollock disregarded his superiors and informed MacArthur “that the Marines did not like any part of it.” He then proceeded to explain their objections to a proposal that looked good on paper but, in reality, was strategically unsound. Although taken aback by Pollock’s frankness, MacArthur listened and “after another perfunctory remark or two he strode from the meeting.”

The strong protest from the Marines paid off. Shortly after the discussion, a memo was received stating, “as a result of the conference held … on 14 December, decision was made to eliminate paratroops from BACKHANDER operation.” The leathernecks would also remain intact as a division.

General Hitoshi Imamura, the highest ranking Japanese officer on New Britain, had his headquarters at Rabaul. His command, the Eighth Area Army, contained the 17th and 18th Armies, which were scattered throughout the Southwest Pacific. Three of his divisions from the 18th were fighting on northern New Guinea, while units from the 17th were operating on Bougainville in the northern Solomons.

Not much was left for New Britain. One lone division was in the central and western portion of the massive island, led by Lt. Gen. Yasushi Sakai, and one solitary brigade was responsible for the defense of the region from Iboki in the north to Arawe in the south. Designated the 65th Brigade, it was commanded by Maj. Gen. Iwao Matsuda, whose expertise was in transportation, not infantry tactics. His polyglot force consisted of the 141st Infantry, which was combat tested in the Philippines, headed by Colonel Kenshiro Katayama. The other unit, the 53rd Infantry, was commanded by Colonel Koki Sumiya. Colonel Jiro Sato’s 51st Reconnaissance Regiment completed the main force.

Thousands of support personnel were recruited to fill the ranks of these depleted commands. These orphan units were handed the difficult assignment of defeating the Marines in western New Britain. In all, the Japanese totaled a little more than 12,000; however, many were noninfantry with no combat experience.

To make matters worse, the terrain that Matsuda’s troops occupied was far-reaching and exceptionally demanding for maneuver because of the swampy morass and dense rain forests that dotted the land. A variety of insect life, reptiles, and other creatures inhabited these jungles as well. According to the official records: “Decay lies everywhere just under the exotic lushness, emitting an indescribable odor unforgettable to anyone who has lived it. Insect life flourishes prodigiously: disease-bearing mosquitoes and ticks, spiders the size of dinner plates, wasps three inches long, scorpions, centipedes.”

Matsuda, however, was a resourceful leader and deployed his men to the west and south where, he felt, the enemy posed the greatest threat. The 53rd Infantry, about 4,000 strong, established positions near the airdrome and adjacent to Borgen Bay. The 141st was scattered in the south and east.

Although morale was sinking, these men still considered themselves superior to any American soldier. They were imbued with the warrior spirit, known as the Bushido Code, the way of the Samurai. Their honor was at stake, and they would fight to the death no matter how many leathernecks came ashore.

A week and a half prior to the invasion of Cape Gloucester, the U.S. Army’s 112th Cavalry Regiment disembarked at Arawe on New Britain’s southwest shore. Originally, its objective was to clear the area to erect a radar site and a PT boat base. Both of these objectives would prevent Japanese air and land forces from coming to the aid of the units defending the Cape Gloucester region to the north.

Ultimately, both of these goals were scrapped. The landings were simply a distraction for the main one at Gloucester. Reinforced by the 158th Regimental Combat Team and the Marines of Company B, 1st Tank Battalion, the cavalrymen nevertheless drove the enemy from the nearby airfield. By February, Arawe was secure.

Meanwhile, the Japanese did not have long to wait for the arrival of the Marines. As the sun’s first rays peered over the horizon, one of Colonel Sato’s forward observers saw the American flotilla near the northern coast of the island; their obvious objective was Cape Gloucester with its all-important air strip. Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey had taken his Task Force 76 northward from Buna harbor in New Guinea, through the narrow Vitiaz Strait, and moved eastward to approach Cape Gloucester from the northwest.

The Japanese 53rd Infantry would bear the brunt of the initial assault of the “butchers of Guadalcanal,” the name given to the Marines by Tokyo Rose, the female mouthpiece of Radio Tokyo.

As the riflemen splashed ashore, they encountered little or no resistance due in large part to the plant life and shrubbery that encroached on the entire area right to the water’s edge. Matsuda had established positions on either side of the dense jungle. The Marine landings had fortuitously separated the two enemy forces and cut them off from each other.

About 7:45 am, Lt. Col. William R. Williams’s 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines hit the beach. Several minutes later the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, under Lt. Col. John E. Weber, did likewise. It was not the familiar chatter of Japanese Nambu machine guns that greeted them but a wall of solid green foliage. Soon, the noise of men hacking away at the underbrush with machetes could be heard—a sound that would become all too familiar during the ensuing weeks. Before long, the Marines began calling Cape Gloucester the Green Inferno, and for good reason.

The advancing columns soon came upon an open stretch of ground referred to as the “Damp Flats.” Said one disgusted infantryman: “Time and again members of our column would fall into waist-high sink holes and have to be pulled out. A slip meant a broken or wrenched leg.”

Marines were swallowed up by the oozy muck that resembled quicksand. Heavily laden leathernecks could not pull themselves up if they were unlucky enough to become stuck. They would have to rely on their fellow Marines to assist. Another hazard were giant trees that were rotted or had been struck by shrapnel from the naval gunfire or aircraft that had strafed the area earlier. The slightest tremor would cause them to topple over with a resounding crash. Sadly, the first casualty at Cape Gloucester was produced by a falling tree.

As the 1st Marines pushed forward, Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines seized Target Hill. Company A knocked out a 75mm gun emplacement that luckily could not be swung around so it could pour fire on the landing craft when the leathernecks had come ashore. As the 1st Battalion set up positions, the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines advanced 900 yards inland, establishing a defensive perimeter in the center of the line.

As the 7th Marines were involved in minor skirmishes, the 1st Marines made their way to the airdrome. Company K, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines spearheaded the attack. As the riflemen moved toward their objective, they ran headlong into a series of rifle pits and interlocking trenches. The assault, unfortunately, did not go according to plan. The shells from the bazookas just bounced off the bunkers, which were covered with soft dirt, inflicting little or no damage. Flamethrowers were brought up but failed to ignite no doubt due in part to the excessive dampness.

An Amtrac drove forward to resupply the men with ammunition. With its .50-caliber Browning machine guns blazing, it pushed ahead to provide covering fire. Unfortunately, the tracked vehicle became bogged down when it lodged itself between a pair of trees. The Japanese emerged from their bunkers and piled on the Amtrac, killing the two machine gunners. The driver, however, managed to extricate himself and rushed forward, driving over one of the enemy positions. The weight of the vehicle caused the bunker to collapse, and the leathernecks swarmed over the emplacement, killing all of its occupants with grenades and small-arms fire.

While the infantry was gaining ground, the artillery of the 1st and 4th Battalions, 11th Marines was lumbering off the LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks). Aerial photographs taken prior to the landing had discovered a large swath of kunai grass that would be an ideal place to set up the 105mm howitzers. As the big guns moved forward, the Marines were horrified to learn that a 40-yard patch of seemingly impassable swampland hindered their advance.

To help pull the cumbersome howitzers through the thick mire, an extra set of wheels had been placed next to the guns’ original tires. Once again the ubiquitous Amtrac, together with TD-9 International Harvester diesel tractors, also assisted in getting the artillery to the dry ground so the gunners could register their weapons to support the infantry. Even with the help of the tractors, equipment became trapped in the unforgiving mud.

“One of the guns and its TD-9 tractor bogged down while crossing the swamp and all that remained above the mud was five inches of the gun shield and the driver’s seat, exhaust pipe and a few levers of the prime mover,” recalled one Marine.

At mid-afternoon on D-day, the enemy conducted its only air strike of the campaign. Two dozen bombers and 60 fighters suddenly emerged from the clouds with their guns blazing, strafing everything in their path. At the same time, a number of Army Air Corps B-25 bombers were en route to bomb enemy positions when they became entangled with the Japanese aircraft. Navy antiaircraft gunners aboard LSTs just offshore regrettably shot down several American planes and seriously damaged two others.

The enemy planes, which had flown from Rabaul, did score some hits on a few of the ships anchored off Cape Gloucester. One American destroyer suffered extensive damage and later sank amid geysers of water caused by her exploding depth charges. An estimated 100 sailors died, and numerous others suffered from agonizing injuries. Despite this tragedy, the enemy had lost most of its aircraft in the daring daylight raid.

On the afternoon of the first day, the torrential downpours arrived. The incessant rains lasted for hours and would occur nearly every single day for the next 90 days or so that the leathernecks remained on the island. Hurricane winds blew in like a maelstrom, and bolts of lightning cracked, temporarily blinding the troops if they struck ground close by. The raucous claps of thunder were so loud it was hard to distinguish them from the sound of gunfire.

The horrible climate was proving to be as detrimental to the Marines as the Japanese. The 1st Marine Division after-action report gives a vivid description of the hardships the men faced: “Rains continued for the next five days causing the ground to become a sea of mud. Water backed up in the swamps in the rear of the shore-line making them impassible for wheeled and tracked vehicles. Amphibian tractors were the only vehicles able to transport ammunition and food to troops in the forward areas. The many streams that emptied into the sea in the beachhead area and along the route of the advance toward the airfield became raging torrents and increased the difficulties of transportation. Troops were soaked to the skin and their clothes never dried out during the entire operation.”

Despite the torrential downpours, Sumiya hurled his 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry against the center of the Marine perimeter. Fixed upon the concept of “annihilate-at-the-water’s edge,” he was so sure he could defeat the leathernecks that he did not postpone the attack until the 141st Infantry could arrive on the scene to bolster his forces.

From 3 am until daybreak, the banzai assaults struck the lines of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines. Amid the crashes of thunder and the occasional flashes of lightning, the fighting, at times, was surreal. The rain came down so heavy it quickly filled the defenders’ foxholes. The Marines had to get out to meet the enemy on level ground. Many of the weapons malfunctioned because of the dampness and mud. The mortar teams fired virtually by dead reckoning to support the infantry, although one officer later remarked that it was “invaluable.” Augmented by Company D of the Special Weapons Battalion, the Marines fought off the Japanese, who left 200 dead sprawled on the battlefield when the fighting was over.

Rupertus pushed his men to continue their quest to capture the airfield. The 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 1st Marines met stiff opposition at a place they named Hell’s Point. Here they encountered a dozen massive bunkers occupied by 20 or more enemy soldiers. Using combined tank-infantry tactics in atrocious weather conditions, the leathernecks easily destroyed the emplacements and killed most of their inhabitants. Although the Japanese had 75mm cannon, they proved ineffective against the tanks. The Marines suffered light casualties but once again the enemy sustained nearly 300 dead.

During the battle, the Marines had a stroke of good luck. They discovered a lone enemy soldier buried up to his neck in the thick mud. This fortunate individual, although wounded in the shoulder, willingly informed them of his unit’s whereabouts, size, and impending plans, which included being reinforced by the 141st Infantry. Instead of continuing the assault, it was decided to await the arrival of the 5th Marines when intelligence officers heard this information. When the fresh battalion landed, Colonel John Selden immediately conferred with Rupertus, Pollock, and 1st Marine regimental commander William J. Whaling on their next move.

The 1st Marines were ordered to press forward along the road as they had been doing. Selden’s men would proceed to the left to stop any enemy that might be retreating in that direction. Both the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 5th Marines ran headlong into the miserable terrain the rest of the division had come across during the previous two days. One stream in particular varied in depth from several inches to more than five feet, hampering their progress.

Fortunately, to the Marine’s amazement, the enemy offered a lackluster defense. As the 11th Marines’ howitzers roared, the tanks and infantry emerged from a large stretch of rain forest to commence their move upon the airfield. As this happened, the rain miraculously halted and a brief interlude of sunshine appeared through the clouds. The tracked vehicles churned ahead with their 75mm cannon and machine guns firing, the riflemen walking behind them for protection. During the attack, an Army amphibious DUKW with a rocket launcher mounted on it let loose a barrage of the projectiles. Soon, the 1st Marines had overrun the airfield. When the 5th Marines arrived, they immediately set up positions on its western end that extended all the way to the beach area.

With the seizure of this vital section of the island, General Rupertus wasted no time in firing off a message, dated December 31, to Krueger at Sixth Army Headquarters: “First Marine Division presents to you as an early New Year’s gift the complete airdrome of Cape Gloucester. Situation well in hand due to fighting spirit of troops, the usual Marine luck and the help of God … Rupertus grinning to Krueger.”

So far, the Marines had punished the Japanese on New Britain at every action. Part of the problem for the Japanese was the ineffectiveness of their leader who was far removed from the scene. Matsuda had prepared a comfortable headquarters for himself. Situated about five miles from the beachhead, it was well equipped with all the amenities, including sake, beer, and even bottles of American Coca-Cola.

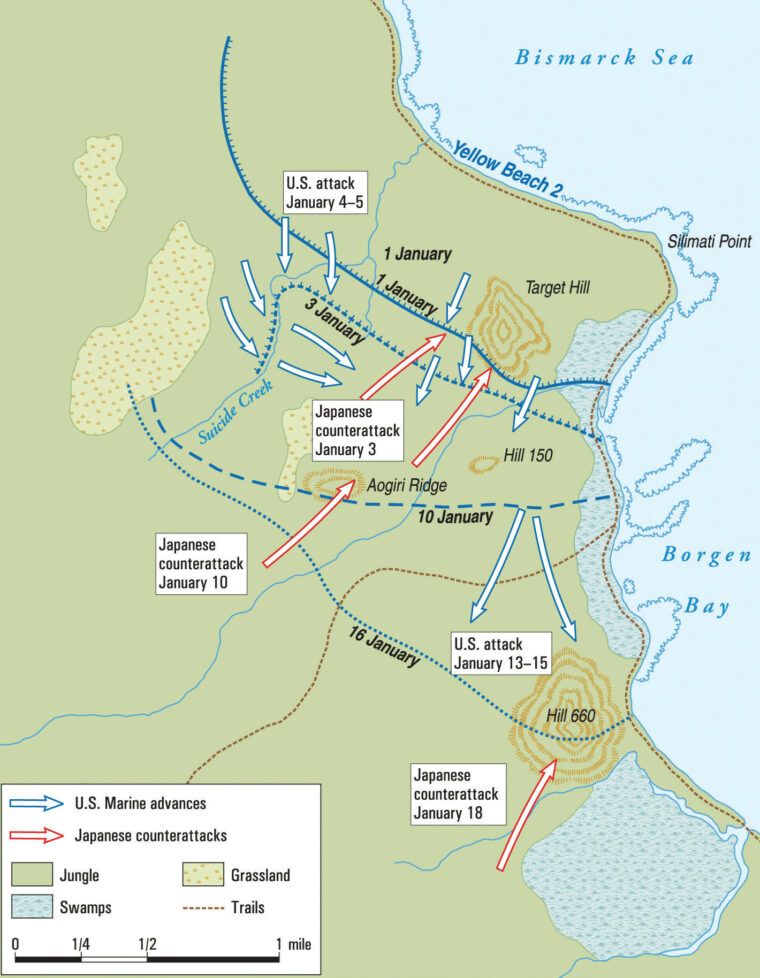

Taken by surprise at the landings, Matsuda nonetheless moved piecemeal in attempting to thwart the Marines’ movement. Being so distant from the action certainly did not help the situation, and his intelligence reports had grossly underestimated the U.S. strength. He dispatched Katayama’s 141st Infantry to oust the leathernecks from Target Hill, near Borgen Bay. Unknown to Matsuda, Rupertus had ordered his assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, “to clear the enemy from the Borgen Bay area.” It seemed the two forces were on a collision course.

The following day, January 3, the 5th Company from the 141st Infantry, led by a Lieutenant Abe, smashed into the Marine perimeter on Target Hill. Although the Japanese had plenty of supporting fire to cover the infantry attack, it proved largely unproductive. One errant mortar shell did score a direct hit on a machine-gun emplacement, immediately killing two of the men manning the weapon. Fortunately, the gunner survived and continued firing 20 belts of ammunition to impede the enemy’s progress.

At dawn, the assault weakened and died. After investigating the ground in front of their position, the leathernecks found 40 or so dead Japanese. It was later estimated that as many as 200 were killed in the botched attempt to penetrate their lines.

The body of Lieutenant Abe was also discovered. “He appeared to have all his worldly possessions with him,” commented Captain Marshall W. Moore. “As well as I can remember he had on two pairs of pants, two or three shirts, a raincoat, and was carrying a heavy pack with a coat strapped to the pack. This was in addition to his sword, pistol and entrenching tool. He carried all this equipment while leading the attack up this steep hill.”

Once again, the enemy had bungled an effort to deal a devastating blow to the Marines. Instead of utilizing all of his force and his supporting fire in a more effective manner, Katayama launched an all-out stab at the perimeter with an understrength company. It would be the trademark of the Japanese defense at Cape Gloucester and would ultimately prove to be their downfall.

While the Japanese were being ousted from Target Hill, Shepherd sent units swinging to the right as his left flank held firm. His riflemen soon encountered a small stream where, unknown to them, the enemy had built positions to counter their movement. The meandering river ran in a north to south direction, and here the Japanese established some extremely formidable fortifications.

As the infantrymen splashed across the stream and ascended its bank, elements of the 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry let loose a broadside of firepower. Unable to see their assailants, the leathernecks shot blindly into the thick underbrush hoping to hit something. It was as if “the jungle exploded in their faces,” described one war correspondent. The stream was given the name “Suicide Creek.”

The men quickly retreated across the stream, dragging their wounded with them. Throughout the day, patrols attempted to find a soft spot in the enemy’s bulwarks. With each probe, however, they only ran into heavy automatic weapons fire. Air and artillery support were fruitless.

For the next several days, engineers from Company C, 17th Marines feverishly toiled to construct a small causeway across the coastal swamp so tanks could get across to aid the beleaguered riflemen. When the log road was finally finished, another serious problem arose. The Sherman medium tanks could not maneuver over the 12-foot-high bank of the river that blocked their way.

To remedy this, a bulldozer drove up to level the bank. Upon seeing this, the enemy concentrated its firepower on the vehicle, eventually hitting the driver. When a second Marine jumped in the driver’s seat, he, too, was cut down by enemy bullets. Finally, one innovative engineer remained on the ground and controlled the dozer by using a shovel and an axe handle to complete the dangerous work. The following morning, three of the tanks cautiously made their way across the causeway and obliterated the Japanese gun emplacements with their 75mm cannon. Infantrymen shot any retreating soldiers as they scampered from their fighting holes. Forty Marines died and another 200 were wounded during this two-day battle, a high cost to pay for a small stream in the middle of a fetid jungle.

The Marines were not the only ones finding the weather and terrain of Gloucester unforgiving. In his journal, Major Shinjiro Komori, commanding a unit near Arawe, scratched these words: “Our losses to date are 65 killed, 57 wounded, and 14 missing. Ten men have perished from fever. Malaria is our main problem, with dysentery a close second. I do not know of a man who does not have one or the other, or both. Air drops become less frequent, possibly because of the loss of our airfield at Cape Gloucester. Most of our supplies are coming in under cover of darkness by barges. I am sending our most critical hospital cases of sick and wounded out with these barges. The enemy has been shelling us continually now for the last two days.”

Even though they were suffering terribly, the soldiers of the emperor would not cease in their determination to hold Gloucester. A message was uncovered from the body of an officer slain during the action at Target Hill. It contained a line that baffled the Marines: “It is essential we conceal the fact that we are maintaining positions on Aogiri Ridge.” Although Aogiri Ridge was not marked as such on their maps, Shepherd realized it had to be one of the hills adjacent to Target Hill. He was determined to discover where it was situated and why it was so vital to the enemy.

The assault jumped off on January 6. U.S. Army B-25s saturated the terrain with bombs while the howitzers of the 11th Marines lobbed shell after shell into the area. As the riflemen of the 7th Marines pressed forward on a front that spanned 2,500 yards, they ran into heavy fire from the center of the line. The ground “rose precipitously and terrific machine-gun fire covered every avenue of approach,” according to a 1st Marine Division action report. The Japanese were defending this tract of land to the death. The leathernecks had stumbled upon an enemy supply route from the Cape Gloucester headquarters to the Borgen Bay region. “The trail was well defined, with a bridge in excellent condition crossing the swamp inland of the beach area,” stated the official USMC monograph on the campaign.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis “Silent Lew” Walt brought his 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines into the fray to reinforce the lines. Walt was no stranger to combat. As a young captain he had led a company of Raiders on Tulagi and Guadalcanal. As the men ascended the hill, many became casualties to an unseen foe. The jungle was so thick, the infantrymen could only see a few yards in front of them.

By late afternoon, Walt’s battalion had miraculously managed to gain a foothold on the slope. During the fighting a 37mm cannon, the lone heavy weapon for the unit, was pushed upward to be placed into position to aid the infantry.

According to the battlefield report: “It was then that Lieutenant Colonel Walt’s leadership and courage turned the tide of battle. Calling forward the 37mm gun he put his shoulder to the wheel and with the assistance of a volunteer crew pushed the gun foot by foot up Aogiri Ridge. Every few feet a volley of canister would be fired. As members of the crew were killed or wounded others ran forward to take their places. By superhuman effort the gun was finally manhandled up the steep slope and into position to sweep the ridge.”

The battle lines of the Marines and the Japanese were only 10 yards apart in certain spots. A total of 37 log and earthen bulwarks, equipped with automatic weapons and interconnecting tunnels, reached for more than 200 yards along the crest of the ridge. Exhausted from the climb (Walt himself had pulled both of his arms out of the sockets), the leathernecks dug in awaiting the inevitable banzai attack.

The Marines did not have long to wait. Just after midnight, the enemy descended upon their lines like a horde of locusts, screaming at the top of their lungs and brandishing swords over their heads.

Pharmacist Mate 1st Class Herman Billnitzer was situated near the 37mm howitzer that the Japanese wanted to eliminate. “We cut loose with all the firepower we had,” he remembered. “Artillery shells were exploding and men were hollering, crying and dying. The noise was so intense you could not hear yourself scream.

“The cries, groans, screams of the dying and wounded were beyond human description—we were in the very jaws of death and hell,” Billnitzer continued. “The cry for corpsman was clear … and [I moved] from one to another giving shots of morphine; few battle dressings were put on as it was totally dark. I could only feel the warm blood and give pain relief.”

In all, the Japanese human waves smashed at the perimeter five times during the night. During the fourth attempt, a major and several other officers made their way behind the lines near Walt’s position. As Walt knelt in the darkness, prepared to kill the Japanese officer, a burst from a mortar shell struck him down.

“The Jap major … was about 50 yrs of age and medium build,” Walt later wrote. “He actually died three paces from where I was crouched .45 in hand waiting for him.”

For his exceptional bravery, Walt would be awarded a Navy Cross, and Aogiri Ridge would be renamed Walt’s Ridge, in his honor.

A saddle located between Hill 150 and Walt’s Ridge was attacked on January 11 by the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. Once it was in their hands, Lt. Col. Henry W. Buse, Jr., and his 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines assaulted Hill 660. Supported by a special weapons task force consisting of tanks, half-tracks, 37mm field pieces, and an Army DUKW with rocket launcher, the combined arms team took the hill in three days.

With these two objectives in Marine hands, the Japanese had shot their bolt. Rupertus decided to send patrols out to cut off the retreating Japanese before they could reach the safety of Rabaul. Matsuda and a small contingent of survivors took a boat and maneuvered around the Williaumez Peninsula. The party eventually landed at Cape Hoskins, approximately 150 miles from Rabaul.

Colonel Sato and Major Komori, with about 300 men each, took different trails to make their way to Rabaul. The trek was a nightmare for the Japanese. Many were suffering from disease and fatigue. Food supplies soon ran out, and the men were reduced to eating roots and tree bark to stay alive. Physically and emotionally drained, some wandered into the jungle never to be heard from again.

“The stench of death hung over New Britain’s north coast like a miasma,” one Marine later recalled.

On March 26, the leathernecks finally caught up to Sato’s group. Although on a stretcher, the officer bravely stood to meet his attackers. He was instantly gunned down. The remaining enemy soldiers scattered into the jungle. When the firing had stopped, 55 of the detachment lay dead.

Komori met the same fate a few weeks later. His men were so emaciated that they resembled human skeletons. Ironically, his party was a mere 20 miles from safety when he encountered a Marine ambush where he and many of his countrymen were slain. His journal was uncovered by the patrol and eventually given to the Marine Corps historical archives section as one of the prized trophies of the campaign.

Although some historians claim that the Cape Gloucester operation was needless, it did reap tremendous benefits for the Marines in future amphibious assaults. Despite its rocky beginnings, the planning phase went very smoothly. The landings caught the Japanese completely by surprise as well. Also, the use of tanks in jungle fighting was a significant factor in the defeat of the enemy. Engineers and shore party personnel were also cited as providing excellent support in spite of the horrible weather conditions that hampered them.

Despite the valuable lessons learned, 310 Marines paid for them with their lives and another 1,083 were wounded. Japanese losses, although unknown, were in the thousands. Rabaul, situated on New Britain’s Gazelle Peninsula, had, in essence, been neutralized for the remainder of the war. One coastwatcher would later jokingly comment: “And now 40,000 Japanese were held in that same Gazelle Peninsula by 29 coastwatchers and 400 armed natives.”

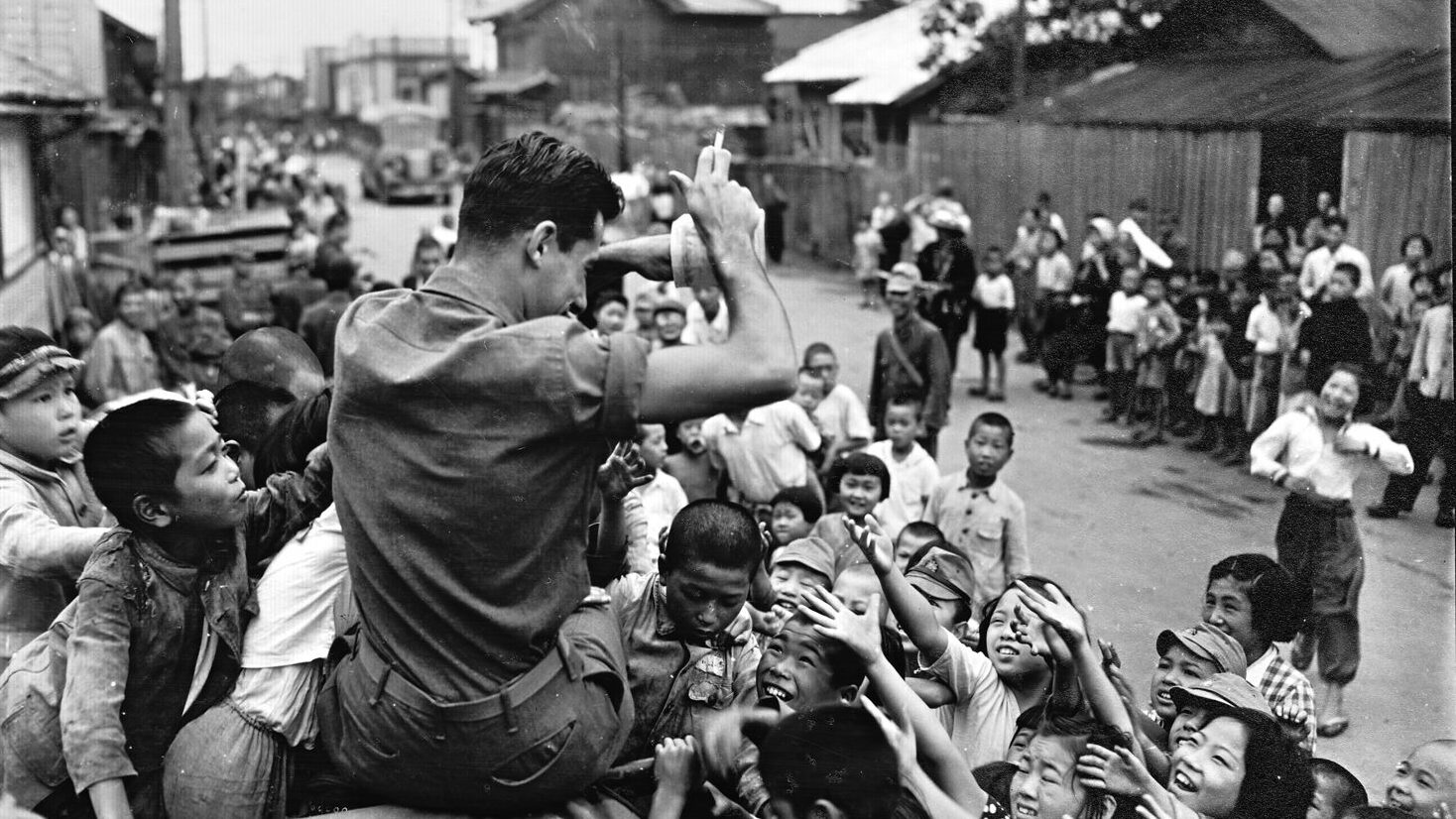

On January 6, 1945, aboard the aircraft carrier HMS Glory, formal surrender ceremonies were conducted. Australian Lt. Gen. Vernon A.H. Sturdee accepted the sword of Gen. Hitoshi Imamura, signaling the end of hostilities. The war was finally over for the Japanese on New Britain.

Frequent contributor Al Hemingway is a Vietnam veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps.

These well written, well researched articles are important stories absent from US history taught in the public schools of Washington (State). These Marines were all heros. Their efforts were superhuman. It is not surprising that their struggle to do their duty and survive were seldom mentioned to their wives and kids after they returned to civilian life.