By Michael Vogel

World War I evokes dreary images of trench warfare, where both sides’ strategy was simply to feed more and more troops into the mincing machine. But in the forgotten theater of German East Africa, an entirely different kind of battle was fought. This was a war waged by maneuver, not attrition, where creativity was more important than materiel and inspired leadership was the driving force behind it all. It was an obscure and lonely campaign, conducted over immense distances, often through unexplored and unmapped areas, in jungles where man-eating lions could pose a worse danger than any human enemy, and it would produce a story of endurance and defiance against almost insurmountable odds.

When the war broke out, Germany’s limited colonial holdings were quickly mopped up by the British, with the exception of German East Africa (now Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi). It was an area of 650,000 square miles of jungles, forests, and bush, where the lack of roads, and maps, the difficulty of the terrain, dangerous animals, and disease were all were formidable defensive weapons. There were the natural dangers—rhinoceroses, elephants, lions, crocodiles, mosquitoes, tsetse flies, chiggers, and ticks. Malaria and sleeping sickness rampaged through the colony, which was surrounded by enemy territory. British East Africa to the north, Northern Rhodesia to the southeast, the Belgian Congo to the east, and Portuguese East Africa to the south. In time, the Germans in Africa would find themselves facing the combined might of India, Great Britain, South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, Belgium, and Portugal.

There were only two railroads in the German colony, one leading from the northern port of Tanga to the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, through the most settled and developed part of the country. A second ran through the middle of the colony from the port of Dar es Salaam to the shore of Lake Tanganyika. The railroads were the key to transportation for the entire area. Roads were scarce and motor vehicles even scarcer. Cross-country transport meant porters carried goods on their heads in the finest safari tradition. Though using human carriers was the only option for moving through the bush, it was also a highly inefficient system. The farther the porters traveled, the more food and supplies they consumed. A flood of goods at the beginning of the supply line would become a trickle by its end. These long, narrow columns also required protection, both from enemy raids and the ever-present natural dangers.

London.

Even worse than the logistics problems was the weak and ineffectual British leadership. Epitomized by the rotund Brig. Gen. Richard Wapshare, who had the distinctly unintimidating nickname of “Wappy,” British leaders in East Africa would prove to be unimaginative, lethargic, and lacking in foresight. The British leadership was fractured—often more involved in infighting amongst themselves than against the enemy. At the beginning of the war, the British consul East Africa, Norman King, reported breezily that “the Germans had no stomach for fighting,” and that the colony would allow the British to occupy it peacefully as long as they were guaranteed security from native unrest and naval bombardment. Unfortunately for King, the government in London had never signed on to such a political agreement, and the captain of the HMS Chatham, Sidney R. Drury-Lowe, mistakenly bombarded the port of Dar es Salaam in late October 1914 after receiving an erroneous report that the German battle cruiser Konigsberg had been spotted hiding in the harbor. Little physical damage was done, but the breaking of the supposed gentleman’s agreement further stiffened German resolve.

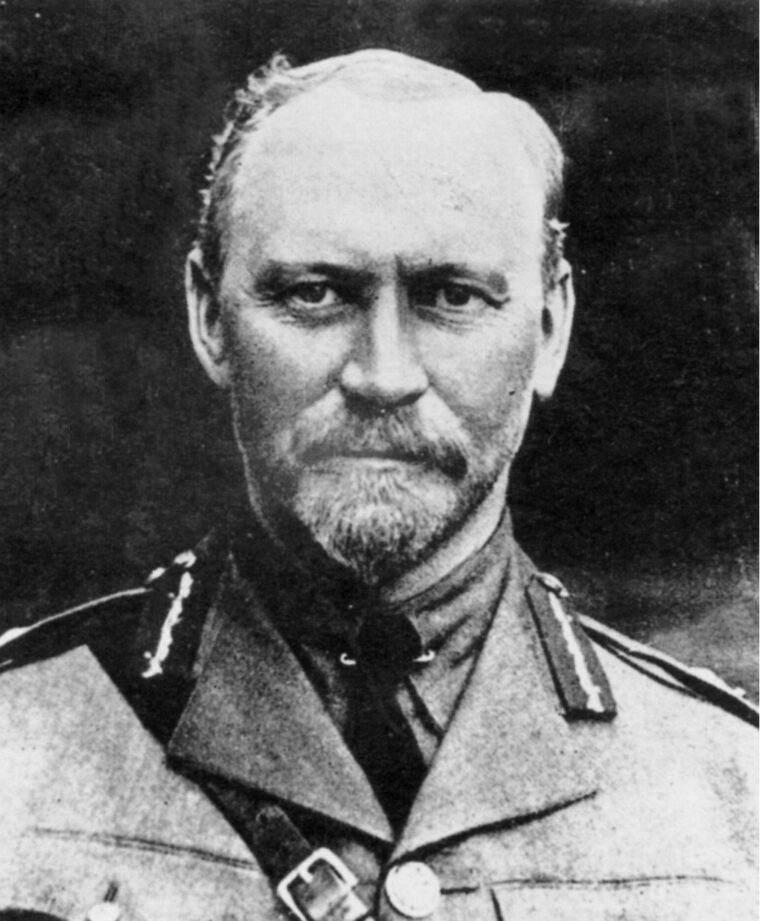

Compared to this ineffectual group of colonial soldiers, the Germans could not have asked for a more capable leader than Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. At 44 years of age, he was an experienced Prussian officer and a veteran of the Boxer rebellion of 1900-01 and the Herero campaign in German Southwest Africa in 1904-06. It was in Southwest Africa that Lettow-Vorbeck learned the techniques of guerrilla warfare. He had learned first-hand the classic principles of guerrilla warfare—mobility, surprise, avoiding pitched battles, self-discipline, strong command, and personal leadership. He also understood just how difficult it could be to completely defeat such a force. Lettow-Vorbeck knew that outright victory over the overwhelming resources of the British Empire was simply out of the question. Cut off from reinforcement or re-supply, and tremendously outnumbered, Lettow-Vorbeck and his army, or Schutztruppe, would be forced to live by their wits. His long-term strategy was to force the British to commit as many troops to East Africa as possible, for as long as possible, to prevent them from going to more important theaters. This was the only way they could have an impact on events in Europe, where the war ultimately would be decided.

“These are jolly fellows to go fighting Germans with”

The basic unit of the Schutztruppe was the company, which contained 16 to 20 German officers and 200 Askaris, or native soldiers. The Germans had learned quickly that Africans made excellent bush fighters. They required less supplies and—perhaps more important—could withstand the harsh climate. Each German company had a supply and transport sub-unit, two to four machine guns and 250 carriers, making it a fully self-contained operational unit. In late September, Lettow-Vorbeck seized the initiative by attacking the Uganda Railroad, which ran parallel to the German border from the port of Mombassa to Nairobi and on to Lake Victoria. This artery was vitally important to the British and threats to it could not be ignored—nor could they be stopped. The Germans used self-sufficient 10-man mounted patrols to cross the waterless wasteland that separated the two colonies. In one two-month period, 30 trains were derailed and 10 bridges destroyed. More and more British troops were sent to guard the railroads, making them unavailable for offensive operations and leaving the initiative firmly in Lettow-Vorbeck’s grasp.

Faced with the surprisingly stiff resistance, the British attempted to use the same strategy in German East Africa that had worked well in the other German colonies: capture the seaports first, cutting the Germans off from outside supply, then advance steadily inland. The British expected the port of Tanga to be an easy target. From Tanga they could move up the northern railroad to Kilimanjaro, taking the most developed part of the colony and eliminating the bases for German raids on the Uganda railroad. The British put together an 8,000-man expeditionary force of inexperienced troops comprised of British territorial and Indian units. In command was Maj. Gen. Arthur Edward Aitken, an old Indian hand who was more concerned with his soldiers’ appearance than their battle readiness. “I will not tolerate the appalling sloppiness in dress allowed during the late war with the Boers,” he announced at his first staff conference. With no evidence or experience to support his claims, Aitken airily pronounced the quality of his opponents to be poor. He should have worried more about his own troops. Captain Richard Meinertzhagen, chief of British intelligence in East Africa, summed them up disgustedly as “the worst in India … rotten.” To make matters worse, the British had virtually no advance intelligence on what they would face on the ground, and no cooperation from naval forces that feared German mines in the harbor. Hoping that overwhelming numbers would make up for their other shortcomings, the British force landed on the East African coast on the night of November 2-3.

The Germans reacted quickly and rushed reinforcements into the area by rail. Unused to fighting in the bush—they had not even known their ultimate destination until they set foot on African soil—the British troops quickly became separated and disorganized in the thick terrain, and the wily Askaris began to take a heavy toll. The leading British units, the 13th Rajputs and the 61st King George’s Own Pioneers, blithely walked into a machine-gun crossfire. Their African porters, showing better sense, threw down their supplies and ran back toward the beach. The Indian troops quickly followed, leaving behind several dead or wounded officers who had tried unsuccessfully to rally them. “These are jolly fellows to go fighting Germans with,” one disgusted British soldier observed.

Lettow-Vorbeck, arriving that night, reconnoitered out front with a bandolier worn across his chest and a brace of pistols on his hips. As fresh reinforcements arrived, he personally placed them in line, regretting as he did that he had no artillery on hand with which to bombard the British beachhead a mile away. “Here in the brilliant moonlight, at such close range, the effect would have been annihilating,” he lamented. His counterpart, Aitken, was not so actively involved. Having set up headquarters in a white house on the bluff overlooking the bay, Aitken leisurely plotted the next day’s moves. He would attack en masse all along the front—no thought to any misdirection—but only after everyone had had “a good breakfast.” It was mid-morning on November 4 before the British resumed their advance.

The subsequent attack was a laughable disaster. Indian units broke and ran, exposing the flanks of their neighboring regiments to German counterattacks. The battle rapidly became a rout. Even nature turned against the British, as the North Lancashire Regiment found their flanking attack stopped cold by swarms of bees. The manmade hives were placed high up in the trees, but errant bullets disturbed the nests. Thousands of angry bees swarmed the soldiers below, inflicting dozens—and in some cases hundreds—of stings. One officer, knocked unconscious by a German bullet, was actually stung awake by the bees and staggered groggily back to the beachhead. Forced to retreat ignominiously, the Lancashires blamed their failure on a German dirty trick. “We don’t mind the German fire,” one soldier told Meinertzhagen, “but with our own bloody crowd firing into our backs and bees stinging our backsides, things are a bit hard.” As it was, the unaffiliated bees had also caused the Germans to evacuate some forward positions, but unlike the British units, the Askaris managed to maintain their battlefield cohesion.

Although outnumbered eight-to-one, Lettow-Vorbeck was eager to counterattack. As soon as new units arrived by train, he pushed them into action. “No witness will forget the moment when the machine guns of the 13th Company opened a continuous fire,” he recalled. “The whole front jumped up and rushed forward with enthusiastic cheers. In wild disorder the enemy fled in dense masses, and our machine guns, converging on their front and flanks, mowed down whole companies to the last man. Several Askaris came in beaming with delight with several captured English rifles on their backs and an Indian prisoner in each hand.” Other Indian troops, not so fortunate, were found later lying dead with their own bayonets protruding from their backs—a stark sign of Askari contempt.

By nightfall, the battle was over. While Aitken and his staff withdrew to their troop transport, Karmala, for what the general shamelessly termed “a good night’s sleep,” the beaten soldiers, English and Indian, spent a decidedly less comfortable evening, hiding in mangrove swamps and trying to make their disoriented way back to the beach. One officer observed: “It is too piteous to see the state of the men. Many were jibbering idiots, muttering prayers to their heathen gods, hiding behind bushes and palm trees and laying down face to earth in folds of the ground with their rifles lying useless beside them. I would never have believed that grown-up men of any race could have been reduced to such shamelessness.” As for their commander, the ever-observant Meinertzhagen found him to be “tired out and disgusted with the whole business. His ambition seemed to be to get away.” Eventually, the War Office would grant Aitken his wish, reducing him in rank to colonel and placing him on half-pay, without active duty, for the rest of the war.

In this, their first major battle in Africa, 8,000 British troops, armed with 16 machine guns and a mountain battery, had been decisively defeated by 1,000 Germans armed with four machine guns and no artillery. The British lost 800 dead, 500 wounded, and several hundred prisoners. German dead totaled 15 Europeans and 54 Askaris. The haste of the British evacuation led to a material windfall for the Germans. Left on the beach were 12 machine guns, 600,000 rounds of ammunition, hundreds of rifles, and enough coats and blankets to last the rest of the war. Alhough well-trained, the Schutztruppe began the war poorly equipped. Eight companies were equipped with 1871 model Mausers that still used black-powder cartridges, leaving a telltale cloud of smoke to give away their firing position. The spoils of victory at Tanga allowed three full German companies to be rearmed with much better British Enfields.

Realizing the shock caused by the disaster at Tanga, Lettow-Vorbeck was quick to follow up his astounding success. Keeping a firm grasp on the initiative, the Germans attacked the British border town of Yassini in January 1915. It was near Tanga and could be used as a forward base for a land assault on that port. Its proximity to the German railroad system allowed nine companies to be rapidly transferred into the area. Lettow-Vorbeck’s plan at Yassini was to set up the British and put them in a position where a conventional response would be a serious mistake. The Germans quickly encircled the 250-man garrison and occupied the hills around the town. Repeated British relief attempts ran headlong into well-sited German machine guns, and the British were forced to withdraw after suffering heavy casualties. The canny Lettow-Vorbeck also used heat and thirst as weapons against the encircled British forces. On January 19, the British garrison at Yassini surrendered to a force half its size. Although an impressive victory, Yassini caused heavy losses for the Germans, too, losses Lettow-Vorbeck realized he could not afford to take if his forces were to last out a long war. For the time being, however, the British remained on the defensive, leaving the initiative firmly in Lettow-Vorbeck’s hands.

Invaded From All Directions—The British Attack

The defeats at Tanga and Yassini, along with Lettow-Vorbeck’s constant raids on the railroad north of the border, were a festering insult to British prestige, and far-reaching changes were made in May 1916. The ineffectual Wapshare, Aitken’s replacement, was replaced in turn by South African general Jan Smuts, who had fought a guerrilla war of his own against the British during the Boer War at the turn of the century. Smuts was an entirely different type of soldier than Aitken or Wapshare—forceful, aggressive, and determined to achieve victory. Along with him came the South African Expeditionary Force, 18,700-men strong. This was part of a concerted British buildup that would total almost 45,000 men by the spring of 1916. Facing this huge force on the northern border were a mere 6,000 German troops. It was only a matter of time before the weight of those disparate numbers would make themselves felt.

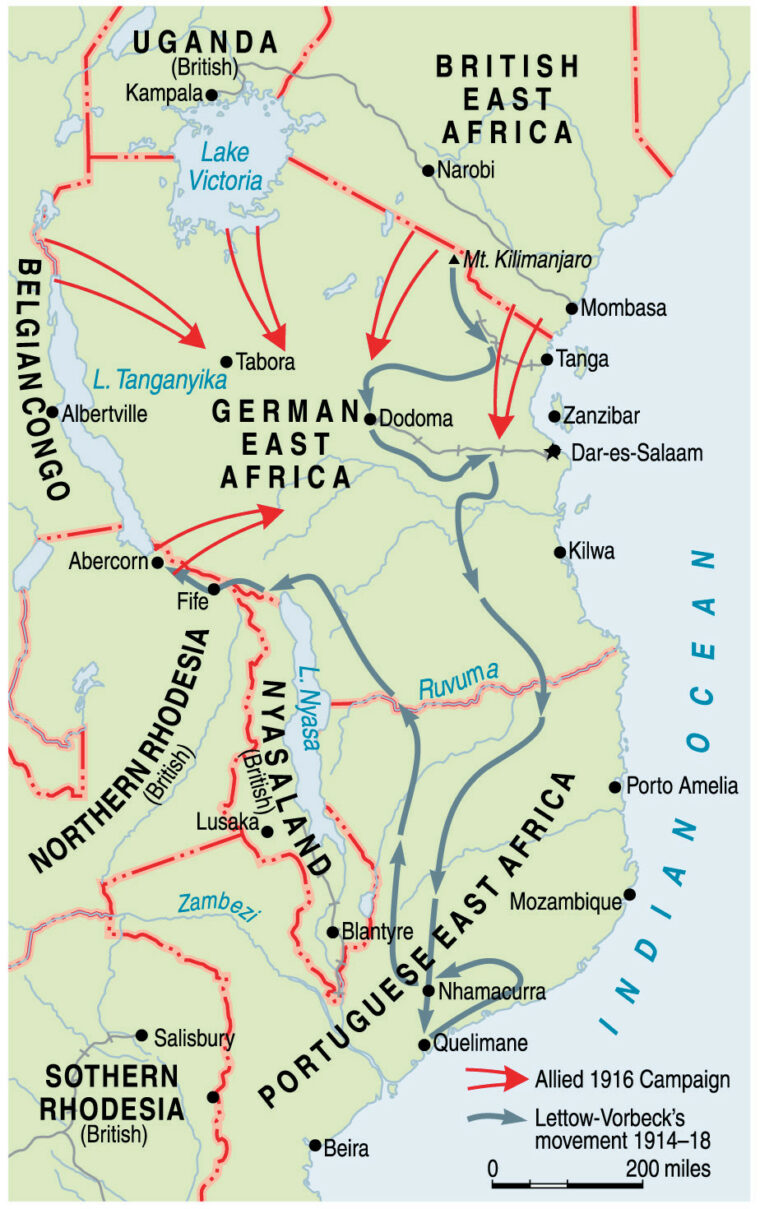

Beginning in April 1916, the German colony was invaded from all directions. The British launched a two-pronged assault from the Kilimanjaro area, taking the developed northeast section of the colony and cutting the northern railroad. To add to Lettow-Vorbeck’s woes, another invasion was launched from Northern Rhodesia, while a Belgian column moved from north of Lake Tanganyika, and another British column headed south from Lake Victoria. In addition, seaborne landings took Dar es Salaam and other minor ports in the south in September, completely cutting off the Germans from the outside world. With their only choice retreat or fight major battles against tremendous odds, the Germans withdrew from the northern part of the colony. This set the pattern for the future campaign. Lettow-Vorbeck would slowly retreat, fighting just enough to weary and tax the British, always careful not to suffer too many casualties himself, taking every advantage of the terrain, and using every ounce of guile and wiliness he possessed to keep the enemy tied down in East Africa.

As more troops were dispatched, the sheer size of British forces in the African theater became a supply nightmare and its own size became self-defeating. This difficulty in supply often meant that smaller forces advanced from different supply bases, and the inability to concentrate their forces led to many opportunities for the Germans. Lettow-Vorbeck could concentrate his forces quickly and attack converging columns one at a time from interior lines. He could also anticipate the British since they had to base their supply system on a port or railroad. Moving away from their bases meant using human carriers or at best horses and mules. The British were to use tens of thousands of carriers, of whom nearly 50,000 would die by the end of the war, primarily from disease. In addition, nearly 140,000 horses and mules died—and still the supply system failed. The British outstripped their supply lines and were often reduced to starvation rations. Short rations, shortages of medicine, and ever-present disease led to a steady attrition of British forces, whether or not they came into contact with the enemy. As the Germans withdrew, Lettow-Vorbeck tried to exploit all food resources in a given area so that it could not support the enemy. From May 1916 on, the campaign in German East Africa became known by those who fought it as “the hungry war.”

Isolated from the outside world, the Germans became increasingly self-reliant. Lettow-Vorbeck compared the improvised German economy to “the industry of the Swiss Family Robinson.” Motor fuel was made from coconuts. Boots were made from skins of cattle and game, the soles cut from captured saddles. A cottage weaving industry was established to produce cloth for uniforms. Quinine, the all-important drug used to treat malaria, was made from wood bark. Among the troops it was jokingly known as “Lettow-Schnapps,” and many complained that its flavor was worse than the disease. Any and all assets were put to work. The German cruiser Königsberg had holed up in the estuaries of the Rufiji River after sinking the British cruiser Pegasus in Zanzibar harbor. The British sent two 6-inch Monitors all the way from Malta to sink her, which they did in July 1915. The Germans salvaged the guns, built carriages for them, and used them until October 1917, when they finally gave out.

Unable to bring Lettow-Vorbeck to bay, the British steadily pursued the Germans. Pushed into the southeast corner of the colony, Lettow-Vorbeck faced an agonizing decision. With the Allies in control of almost the entire colony, there was no shame in surrendering after a well-fought campaign. But as long as a German army could remain in the field, his original mission of tying down British forces was still viable. Even after the long retreat, morale among the Askaris was still high. Lettow-Vorbeck was not one to give up and it was his indomitable spirit that the troops followed. “There is almost always a way out, even of an apparently hopeless position, if the leader makes up his mind to face the risks,” Lettow-Vorbeck said.

Given the options, he decided to evacuate German East Africa and invade Portuguese East Africa. It was a plunge into the unknown. The Germans had neither maps nor any real idea of what they would face on they got there, but Lettow-Vorbeck was undaunted. “If we succeeded in maintaining the force on the new territory,” he reasoned, “the increased independence and mobility, used with determination against the less mobile enemy, would give us a local superiority in spite of the great numerical superiority of the enemy.” Accordingly, he reduced the size of his force to one that could be handled well in the bush. German doctors picked the healthiest men, not necessarily the best soldiers, since endurance would be the most important factor. He now commanded an army made up of 300 Europeans, 1,700 Askaris, and 3,000 native carriers. His force would be totally independent of supply dumps and could rely only on what it could capture.

His reorganization complete, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed the Rovuma River on November 25, 1917, evacuating the German colony and invading Portuguese East Africa. The tone for the new phase of the campaign was set immediately. There was a Portuguese fort at Negomano less than a mile from where the Germans were crossing the river. Although his forces were still in the process of making the crossing, Lettow-Vorbeck had personally reconnoitered ahead and found some woods approaching the fort. He ordered an immediate attack using the cover of the woods. The 900-man Portuguese garrison did not put up much of a fight. The Askaris, however, went wild; Lettow-Vorbeck termed it a “fearful melee.” Now the Schutztruppe were not just merely the hunted—they were also the hunters. Among the plentiful supplies they captured were medicines, six machine guns, 250,000 rounds of ammunition, and enough rifles and uniforms to re-equip half the force. “With one blow,” said Lettow-Vorbeck, “we had freed ourselves of a great part of our difficulties.”

“This is a Funny War. We Chase the Portuguese, and the English Chase Us.”

The successful start to the Portuguese East Africa incursion sent German morale soaring to new heights. Although the Portuguese maintained a relatively large and well-equipped army, their dispositions often made then easy pickings for the Germans. Portuguese rule was very unpopular, and their army of over 7,000 men was split into hundreds of small units throughout the country to maintain order. Native dissatisfaction and latent rebellion required local garrisons to conduct ceaseless patrolling. These poorly led small garrisons would seldom put up more than token resistance before fleeing into the bush, leaving their supplies and weapons to the feared German Askaris. By this point in the war the reputation of the Schutztruppe was a potent weapon in itself.

Wherever Lettow-Vorbeck went, the British were forced to follow. The Germans moved south down the center of Portuguese East Africa, stretching the British supply lines from the coast and Nyasaland. Supply proved every bit as difficult for the British in the Portuguese colony as it had in the nearly road less stretches in the southern part of the German colony. The farther inland the Germans went, the less fit the British were to attack them successfully. Lettow-Vorbeck used the terrain and environment in a constant war of attrition on the British. Every man who came down with malaria or fell out from hunger was one more who would not require an Askari bullet. An old Boer serving with the Germans summed it up best. “This is a funny war,” he said. “We chase the Portuguese, and the English chase us.”

Many Askaris had brought their fami-lies with them, and numerous children were born during the march. Bearers, women, and children were taught to march at the same pace as the soldiers. They marched six hours a day, with a half-hour rest period every two hours. This strange parade could cover 15 to 20 miles a day through roadless territory. Rapid mobility was absolutely essential for the survival of the Schutztruppe. The Germans practiced making boats from bark until they could be completed in less than two hours. This allowed for the rapid crossing of the many rivers and waterways without having to carry boats along with them. The march was arduous, and the seriously wounded could not be carried along for long. Lettow-Vorbeck was faced with yet another difficult choice. “There was nothing for it but to collect our invalids from time to time, turn them into a complete field hospital, under a single medical officer, and take our leave of them finally.” Nothing could be allowed to slow down the Schutztruppe. As always, the indomitable will of the commander led the army. Once when he was fever ridden and nearly blind, Lettow-Vorbeck led his exhausted horse into camp. His adjutant noted: “I am not sure which one more resembled a skeleton. One thing is certain. The horse will not last the next 24 hours, but the colonel will.”

Lettow-Vorbeck had to coordinate his tactics with the unavoidable need to procure food. The command was divided into groups of three companies each, with a supply detachment and a field hospital. Each group could operate independently or in combination with other groups. Accidental meetings with enemy patrols happened without warning in the bush, and the Germans could bring their superior firepower to bear almost immediately. As in Europe, the machine gun was king of the battlefield. Brief violent patrol clashes were a common occurrence, and the German-led Askaris usually came off the victors. They would hit hard and quickly, police the battlefield for anything of use, and then disappear back into the bush long before any superior enemy force could arrive. Any advantage was seized on by the Germans. During the dry season, the Askaris would start brush fires to slow the British pursuit, sometimes mounting small counterattacks under cover of the smoke.

The Germans drove almost the entire length of the Portuguese colony, raiding food supplies and capturing small Portuguese garrisons along the way. But food was only one of Lettow-Vorbeck’s requirements for maintaining the fighting ability of his force. Ammunition was becoming critically low, and its procurement became a top priority. But first something had to be done about the tightening net of British pursuit. A British force had landed at Port Amelia and was nearing a linkup with a second force from Nyasaland. Lettow-Vorbeck first struck the Nyasaland force, then turned and inflicted a sharp defeat on the Port Amelia force, once again striking two converging columns from interior lines. The pursuit thus temporarily neutralized the Germans continued their search for ammunition.

The Germans headed for the built-up area around Kokosani, in the southern end of the Portuguese colony. Kokosani was a sizeable town with a railroad, and Lettow-Vorbeck was sure that there would quantities of ammunition somewhere in the vicinity. The Schutztruppe achieved surprise at Kokosani and took the town without much of a fight. But finding no ammunition stores, they moved on down the rail line. At nearby Nhamacurra, the garrison, which had been reinforced with British troops, was ready and waiting. The Germans brought up two field guns and 200 shells they had captured the previous day. The guns, fired from short range, panicked the Portuguese soldiers, making the British position untenable. Their retreat was hard pressed by the Askaris and rapidly became a rout that was blocked by the Nhamacurra River. In attempting to cross the river, many drowned, including their commander. The British suffered 223 casualties out of a force of 300 men, and the Germans collected over 500 Portuguese and British prisoners. Even more important, Nhamacurra turned out to be a main supply depot, and the German victors snatched up vast supplies of much-needed food, medicine and ammunition.

Having run the entire length of Portuguese East Africa with British columns in hot pursuit, Lettow-Vorbeck reversed course and headed north, hoping that the British would think he was headed for Tabora. On September 28, 1918, the Schutztruppe crossed back into German East Africa, rapidly moving north. Tabora was an important town, located on the central railway, and was therefore a linchpin in the British supply lines. It was also the best recruiting area for the Askaris before the British had occupied it. The last thing the British wanted was to allow Lettow-Vorbeck to replenish his ranks. The British rushed forces from all over the colony to protect Tabora and try to bring the German army to bay. Having once again forced the British to dance to his tune, Lettow-Vorbeck veered sharply to the west, avoiding the British concentration around Tabora and invading instead the British colony of Northern Rhodesia.

Always with supplies first in mind, the German force headed toward land as yet untouched by war, where there would be nothing stronger than local police forces to oppose them. The Askaris were in fine spirits, fully armed, and leading a herd of 400 cattle. On November 9, the Germans took Kasama in Northern Rhodesia. They were pleased to find full supply depots, only lightly defended, as they moved farther into Rhodesia. They had more supplies than they could carry and had also captured quinine stocks to last them to June 1919. The Schutztruppe was ready to carry on the war indefinitely. According to Lettow-Vorbeck, “The men were well armed, equipped and fed, and the strategic situation at the moment was more favorable than it had been for a long time.”

German Casualties: 2,000 Killed, 9,000 Wounded

On November 13, Germans reached the Chambezi River. There they received the stunning news from the British commander that an armistice had gone into effect two days before. World War I was over. The Schutztruppe marched into Abercorn two weeks after the end of the war and formally surrendered on November 25, 1918. At the surrender, Lettow-Vorbeck’s force contained 155 Europeans, 1,168 Askaris, and 3,000 other Africans, including 819 women. The weapons they turned over included a Portuguese field gun, 37 machine guns (30 of them British), 1,071 English and Portuguese rifles, 40 rounds of artillery ammunition, and 208,000 rounds of rifle ammunition. Although they had been ready to continue the war indefinitely, the signs of their 3,000-mile trek were all around them. Many men were wearing bandages made from bark, and Lettow-Vorbeck himself was wearing captured boots slit over the toes to make them fit.

Overall, the Germans lost 2,000 killed, 9,000 wounded, and 7,000 prisoners or missing, along with some 7,000 African carriers dead, primarily from disease. The British suffered 10,000 dead, 7,800 wounded, 1,000 missing or captured, and a staggering 50,000 African carriers dead—once again showing how badly Lettow–Vorbeck had stretched British supply lines. Belgian and Portuguese casualties totaled 4,700. Great Britain alone spent £72,000,000, as opposed to the kaiser’s government, which had not even paid its East African soldiers. The fact that the men would fight on without pay for years on end was testament to the loyalty they had for their indomitable leader. British soldiers could claim to fight for God, king, and country. The Askaris had fought for Lettow-Vorbeck.

With their help, Lettow-Vorbeck had accomplished his original aim of tying down as many Allied troops as possible. With a troop total of 3,000 Europeans and 11,000 Askaris, he had successfully faced down, at one time or another, some 300,000 Allied soldiers deployed against him from August 1914 to November 1918. His exploits earned the respect of friend and foe alike. Even England’s Queen Mary voiced her admiration. Lettow-Vorbeck finished the war Germany’s only undefeated general, one who under the harshest of conditions still had managed to fight a gentleman’s war. As one English officer willingly admitted, “We had more esteem and affection for him than for our own leaders.” Met with a hero’s welcome when he disembarked at Rotterdam, Lettow-Vorbeck was characteristically humble: “Everyone seemed to think that we had preserved some part of Germany’s soldierly traditions, had come back home unsullied, and that the Teutonic sense of loyalty peculiar to us Germans had kept its head high even under conditions of war in the tropics.” Indeed it had.

East Africa did not generate much in the way of war films either. This was probably due to lack of interest in that theatre. Two of the more prominent were “The African Queen” with Humphrey Bogart and “Shout at the Devil” with Roger Moore.

In 1964 the German government paid the East African soldiers the wages they were owed.