by Lowell L. Getz

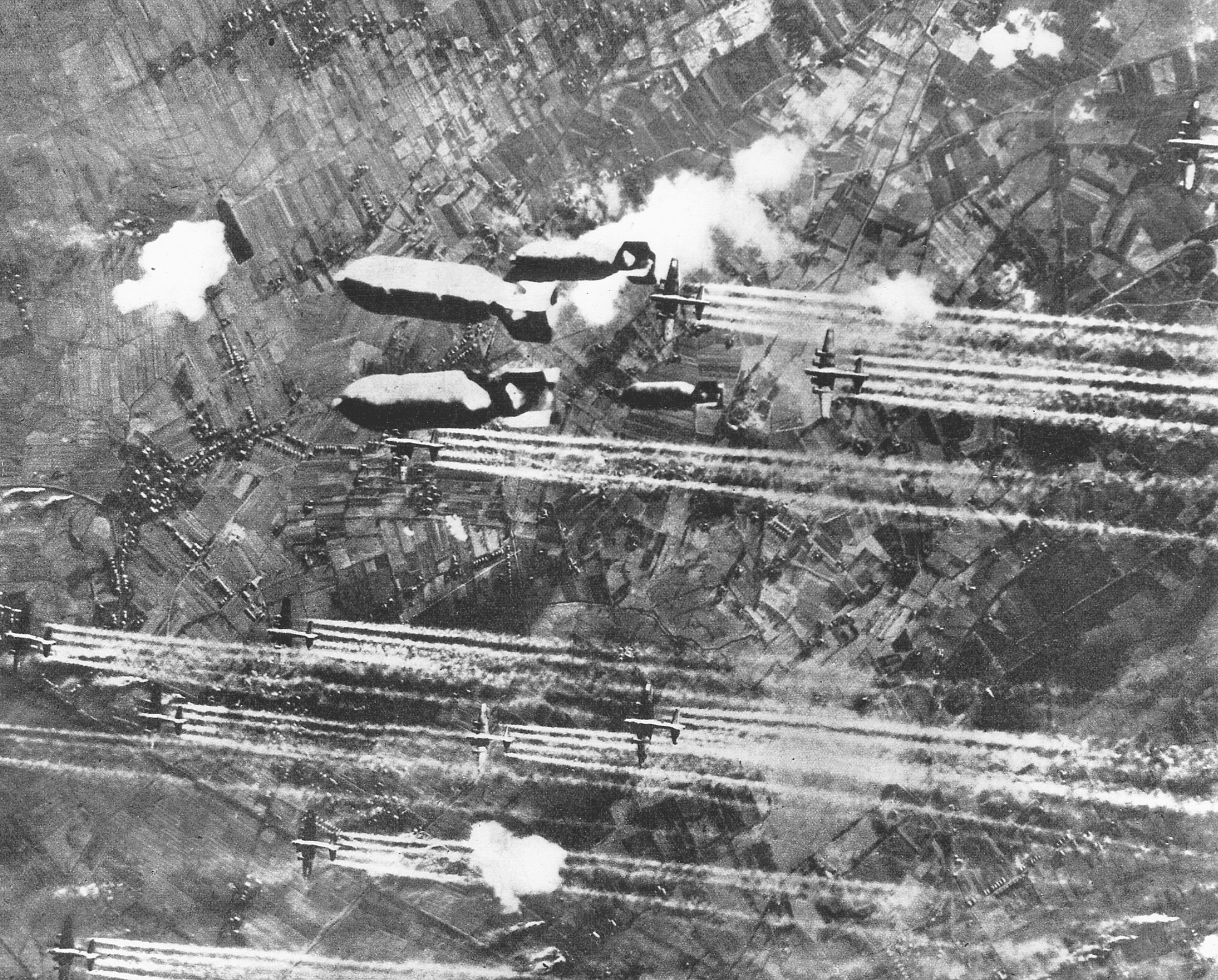

“Bombs Away” rang out over the intercom static of the 29 aircraft of the 91st Bomb Group (Heavy). From each olive drab Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, five 1,000-pound general purpose bombs broke free of their shackles and fell through the open bomb bay doors.

Relieved of the weight, the bombers lurched upward. The high explosives streamed downward onto the Bremen, Germany, Flugzeugbau assembly works of the Focke-Wulf aircraft factory 26,000 feet below. The plant produced about 80 Focke-Wulf FW-190 fighters each month. FW-190s, along with hoards of Messerschmitt Me-109s, were wreaking havoc among heavy bomber formations as they penetrated into German airspace.

Many of the bombs exploded within the factory itself, destroying at least half of the buildings. Others fell on the adjoining airfield and aircraft dispersal areas. The time was 1259 hours, April 17, 1943 and planes of the 91st Bomb Group had been in the air for almost three hours. Thus ended successfully the day’s work for Uncle Sam. From that point on, the air crews were working for themselves. The crewmen’s primary objective for the rest of the day was to return safely to their home base at Bassingbourn, East Anglia, England where a party awaited them. Local English girls, the crewmen’s dates, were already preparing for a night of dancing and general revelry. In a few hours, “passion wagons,” (trucks) would be heading out to nearby villages to pick up the girls and bring them to the airbase.

The Largest Heavy Bomber Contingent to Date

For the April 17 mission, VIII Bomber Command had launched the largest number of heavy bombers over the continent to date in the war. Of the 115 aircraft put into the air earlier that morning, 107 made it to the target, another record. It was a rough mission, even for this period of the air war over Germany.

Weather over the target was clear, perfect for bombing, putting the Germans on guard as to the possibility of an attack on Bremen. Further, a Luftwaffe reconnaissance plane spotted the American formation while it was still well out over the North Sea. German fighter control was alerted as to the likely target, as well as heading, speed, altitude, and number of bombers in the strike force. A “welcoming committee” of 150 German fighters awaited the formations as they approached the enemy coast.

This was the 69th combat mission the 91st Group had flown since its first foray over the continent on November 7, 1942. The 91st and the 306th Bomb Groups, comprising the 101st Provisional Combat Wing (PBCW), with the 91st in the lead, were first over the target that day. They were followed by the 305th and 303rd Groups of the 102nd PBCW. The 91st Group put up 32 bombers that morning, the largest force it, too, had mounted to date.

Heading for the Initial Point

The 91st Group lead aircraft, “Stupntakit,” of the 323rd Squadron, had lifted off at 0956 hours. Other planes followed at approximately 30-second intervals, the last one, No. 399, “Man-O-War,” leaving the runway at 1008 hours. There was considerable ground haze at Bassingbourn during takeoff, reducing visibility to between one and two miles. In spite of this, the pilots did not experience serious problems in forming up on the group lead and heading for the wing rendezvous with the 306th Group.

Weather conditions over the prescribed route to the target were the best they had been for the past month. Although a general ground haze covered the continent and cloud patches were prevalent at 6,000, 14,000, and 20,000 feet over most of the route, at no place did cloud cover exceed 5/10 density. Still, it required considerable skill and a little luck for the lead navigator, Captain Charles F. Maas, to identify checkpoints along the route.

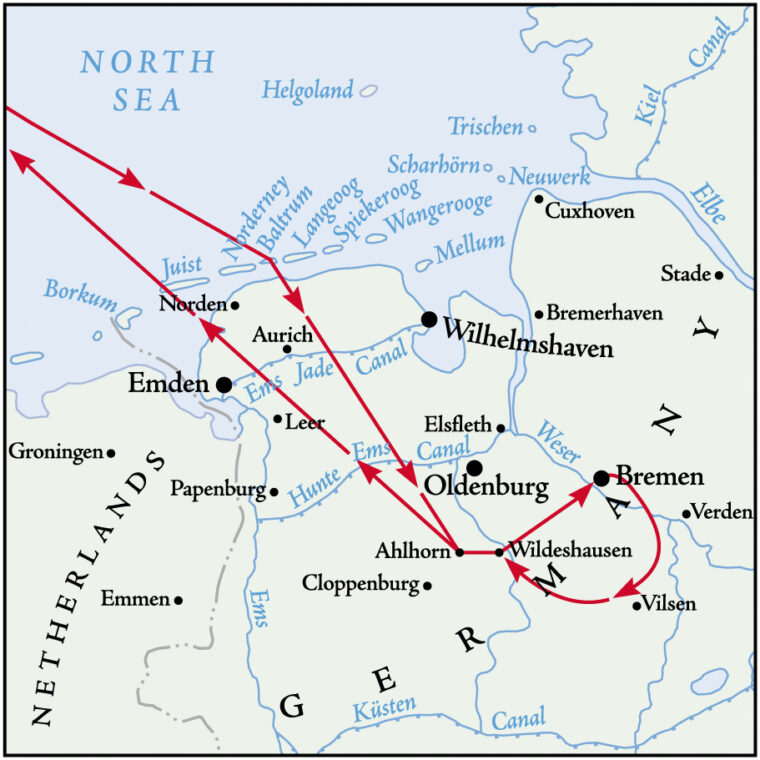

The flight path took the strike force to the northeast over the North Sea, over the East Frisian Islands, and on to Germany west of Wilhelmshaven and Oldensburg. Checkpoints along the way were Baltrum Island, Edewecht, Ahlhorn, and the IP (Initial Point, beginning of the bomb run) at Wildeshausen. The IP was five minutes from the target. The prescribed rate of climb to bombing altitude while over the North Sea was very fast; the bombers had to move from 6,000 feet to 26,000 feet in 32 minutes.

Two Bombers Turn Back Early

This placed considerable stress on the heavily loaded bombers. Two aircraft encountered problems because of the fast rate of climb.

One 322nd Squadron crew in the Composite Group, Lieutenant McGehee Word’s “Piccadilly Commando,” had to return to base. After test firing his .50-caliber left waist machine gun, S/Sgt. Edward A. Murphy lifted the gun back into the aircraft to make adjustments. In doing so, he accidentally hit the trigger, causing the gun to run away inside the fuselage. He shot up the stabilizer, knocked the oxygen system out, and nearly hit the tail gunner, S/Sgt. Marvin E. Dyer. Word turned back at 1230 hours, 15 miles northwest of Baltrum Island.

When the group crossed onto the continent, only 29 of the 32 bombers that left Bassingbourn remained in the strike force. Eight 401st Squadron planes went over the continent, five in the low squadron of the 91st formation and three in the low squadron of the Composite Group.

The Luftwaffe Greeting Party

As the 91st passed over the East Frisian Islands, moderately heavy and accurate flak came up at the formation. None of the 91st Group planes received serious hits. As soon as the bombers passed beyond the range of these antiaircraft guns, German fighters appeared. The fighters did not at first charge into the bomber stream, but gradually picked up the tempo of runs at the bombers until the IP, Wildeshausen, by which time they were mounting vicious attacks on the intruding aircraft. All the while flak continued to come at the strike force from Aurica, Oldenburg, Alhorn, Wildeshausen and of course, Bremen.

Nearly every type of fighter available to the Luftwaffe came at the strike force. Most were Me-109s, but a number of FW-190s also attacked the bombers. Although the majority of the enemy aircraft stormed in on the bombers from between 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock high, attacks were made from almost every conceivable direction. Many of the passes were made by “javelin” formations of several enemy aircraft flying in line directly through the bomber formation. Others swarmed at the bombers in groups of three.

Me-110 twin-engine fighters engaged the bombers at a distance of over 1,000 yards, beyond the protective range of the bombers’ machine guns, firing 20mm and 30mm cannon shells at the planes. Twin-engine Junkers Ju-88s were believed to have dropped aerial bombs into the formation from above. No fewer than 125 single-engine and 25 twin-engine enemy aircraft were estimated to have engaged the strike force.

Captain Maas could not see the IP because of the haze, but rather than diverting to the alternate target, he turned at the time he was supposed to turn on the IP and hoped for the best. He was accurate. Bremen appeared directly ahead, and the bomb run was on course.

The heaviest fighter attacks were experienced at the beginning of the flak barrage at Bremen. Fighters continued coming at the bombers over the target as enemy pilots ignored the exploding flak. It appeared to the bomber crews that the enemy attacks were planned to drive lead elements of the squadrons off the bomb run after the group had been committed, to render the entire bombing inaccurate. Many German pilots pressed their attacks to within 25 yards of the bombers before breaking off. In spite of persistent flak on the run into the target and intensifying fighter attacks on the 91st as the group approached Bremen, all 91st planes that crossed the enemy coast remained in formation over the target.

Despite Damage, ‘Sky Wolf II’ Makes It’s Bombing Run

Just after leaving the IP and beginning the bomb run, “Sky Wolf II” received flak hits and was attacked head-on by German fighters. The windshields in front of both pilots were shattered. Fighters were queuing up off to the left of the bomber, darting ahead, turning over on their backs, and circling back in head-on attacks. Others were coming in from all positions. Some of the enemy aircraft came so close that 1st Lt. Nicholas Stoffel and co-pilot Captain Robert Foster could see their eyes. Crewmen were literally screaming out directions of incoming fighters over the intercom.

One 20mm shell came through the nose of the plane and exploded in the bulkhead just in front of the pilots’ legs, severely wounding the bombardier, 2nd Lt. Everet A. Coppage, in the buttocks. A piece of shrapnel went on through the nose compartment and into the flight deck, hitting Foster in the right leg, causing a gaping wound. Stoffel was wounded in the left leg by the exploding shell.

Foster believed his wound to be serious and knew that he would need immediate medical attention. He went down into the nose to bail out, hoping the Germans would find him quickly and get him to a hospital. When he discovered that he did not have his chute on, he returned to the cockpit, removed the chest pack from under his seat, snapped it on, returned to the nose, and bailed out.

After free floating for a short while, Foster pulled the ripcord. It came loose in his hand. He had to pull the parachute canopy out of the pack by hand. While descending, Foster took his oxygen mask hose and tied it around his right leg to slow the blood still flowing from his wound. He landed heavily in a field and lay there, unable to get up because of his injured leg. A group of angry farmers came running at him from one direction and a small open vehicle with military men in it from another. The military won, and he was taken prisoner. Foster was taken to a hospital in Oldenburg, where he remained for almost five months while his leg healed. He was later moved to the center compound at Stalag Luft 3.

“Sky Wolf II” continued to the target, with Stoffel handling the controls alone. She took more flak hits on the bomb run. The No. 1 engine was set afire while 20mm cannon shells ripped through the rest of the plane. Much of the electrical system was knocked out, and the plane sustained structural damage to the wings and fuselage. Still, “Sky Wolf II” remained in formation.

All of the Bombs are Dropped

The Composite Group also remained intact to the target. In the confusion of evasive action in response to fighter attacks, Lieutenant William Genheimer and “Frisco Jinny” moved ahead of Lieutenant Kenneth Wallick in “The Old Standby,” who ended up flying on Genheimer’s right wing. As the two aircraft turned on the IP, 20mm cannon fire blasted into the top turret of “Frisco Jinny.” The gunner, T/Sgt. Roland E. Hale, was hit in the middle of the back and killed instantly. In spite of the damage to “Frisco Jinny,” the two 322nd Squadron planes continued over the target, dropping with the rest of the formation.

Only two bombers from the entire Strike Force, both from the 306th Group, were lost en route to the target.

Except for “Ritzy Blitz” of the 324th high squadron of the Composite Group, the 91st bombers dropped all their bombs on the target. Three bombs hung up when the bombardier of “Ritzy Blitz,” 2nd Lt. R.W. Stephenson, toggled over the target. He eventually was able to salvo the three remaining bombs, causing them to fall on Ochtelbur at 1329 hours on the return leg of the mission.

Flak over the target was intense, the most concentrated barrage the group had encountered on any mission up to that time. The crews had been briefed that morning that there were an estimated 496 antiaircraft batteries around Bremen. This appeared to be an accurate assessment. The guns put up a solid box of exploding 88mm and 105mm shells. The resulting flak formed a massive black cloud of steel shards over the target.

A Nightmarish Trip Home

The trip home proved to be a nightmare for the 401st Squadron. After bombs away, the prescribed route out of Germany started with a 90 degree right turn off the target, heading south into a sweeping right turn just north of Vilsen, angling back over Wildeshausen, and then to Ahlhorn. From there, the bomber stream made a straight-line run out of Germany, passing east of Emden, west of Aurich and to the North Sea over the west end of Juist, one of the Frisian Islands.

The enemy aircraft did not break off their attacks on the 91st until the group had left the enemy coast and was about 40 miles out over the North Sea. At this time, the strike force was picked up by a formation of 12 British Supermarine Spitfire fighters which escorted the bombers back to England. Only two 401st bombers, both from the Composite Group, were still in the air when the strike force was met by the protecting British fighters.

The Crash of ‘Invasion 2nd’

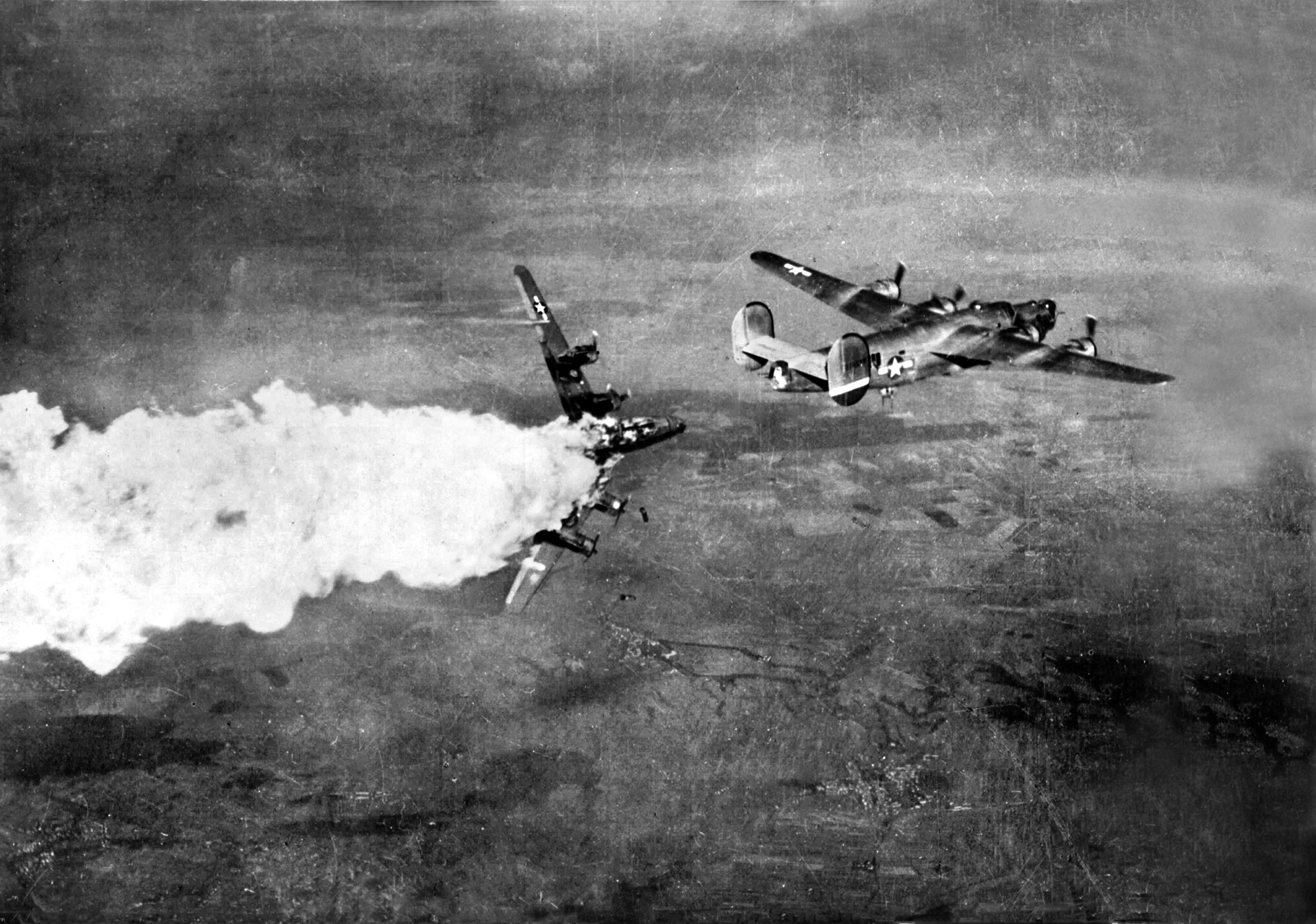

While over the target, “Invasion 2nd” took flak hits and was attacked by German fighters. Three fighters came in head-on at 12 o’clock. They shot the front of the No. 2 engine completely off. The left wing and fuselage were also hit, turning the bomber into an inferno. “Invasion 2nd” was on her way down. The pilot, Captain Oscar O’Neill, rang the bail-out bell and called over the intercom for the crew to leave the aircraft.

The ball turret gunner, T/Sgt. Benedict B. Borostowski, came into the fuselage to the partly open waist door. The door was jammed, and the waist gunners, S/Sgts. William B. King and Eldon R. Lapp, were sitting in front of the door, unable to squeeze out. Borostowski stepped up, put a foot between the shoulders of the two men, and one at a time, pushed them through the narrow opening. The others in the rear of the aircraft had already left. The tail gunner, S/Sgt. Aaron S. Youell, dropped through his tail escape hatch. The radio operator, S/Sgt. Charles J. Melchiondo, and the flight engineer, T/Sgt. Harry Goldstein, went out through the bomb bay.

There was no one left to push Borostowski out, so he went to the tail escape hatch and dropped out. The rest of the crew, including O’Neill and the co-pilot, 1st Lt. Robert W. Freihofer, bailed out through the nose hatch. The bombardier, Captain Edwin R. Bush, detached the Norden bombsight and tossed it out the escape hatch before following the navigator, Captain Edwin M. Carmichael, through the opening.

“Invasion 2nd” crash-landed in an almost perfect landing on the ground near Oldenburg. Five planes were left in the low squadron.

‘Hellsapoppin’ Goes Down

The next 401st low squadron plane to go down was “Hellsapoppin.” Three or four minutes after the target was hit, there was a very hard jolt under the left side of the plane, close to the fuselage. An antiaircraft shell had exploded just under “Hellsapoppin.”

Flak ripped into the left side of the aircraft, tearing off chunks of metal from the fuselage and throwing them through the interior of the plane. At the same time, a three-foot section of the right wingtip was blown off by a flak burst. A one-and-one-half-foot hole appeared in the nose compartment, and all the nose window plexiglass blew out. There was fire in the left wing and nose compartment. The radio room became engulfed in fire from broken oxygen lines.

The pilot, Lieutenant John Wilson, was wounded in the head, and the co-pilot, 1st Lt. Arthur A. Bushnell, was hit in the right eye, both legs, the left arm, and the right hand by flying aluminum. In the nose, bombardier, 1st Lt. Harold Romm was hit in the left leg by flak. Earlier, before arriving over the target, Romm had been hit in the same leg by a machine-gun bullet during an attack by an FW-190.

In the top turret, the flight engineer, T/Sgt. Norman L. Thompson, felt a jolt and saw the left wing on fire. He had just seen a fighter off the left wing going after a plane below and was afraid it would come back up at “Hellsapoppin.” The enemy fighter was about 15 feet too low for Thompson to deflect his top turret guns to get off a burst.

Since the intercom was shot out, Thompson was not certain what was happening to the plane. He stepped down from the turret and went into the cockpit. There he saw both pilots with their oxygen masks off and blood pouring from under their helmets. He assumed both were dead. Thompson had not heard any firing from the gunners since “Hellsapoppin” had left the target. He figured they either had been killed by the flak and fighters or were too seriously injured to move. From the intensity of the fire he knew “Hellsapoppin” could explode at any second.

Thompson took a final glance at the instruments to ensure that the plane was still in level flight. He went back to the bomb bay and opened the doors. After checking below and seeing there was no plane under him, he dropped out.

Almost immediately after Thompson bailed out, the plane broke in two at the radio room. Four others, Bushnell, Barton, Romm, and the radio operator, T/Sgt. Howard A. Earney, were wounded but managed to escape the plane. The rest of the crew remained trapped in the falling aircraft. “Hellsapoppin” crashed 20 miles south of Bremen. Four planes were left in the low squadron.

The Demise of ‘Thunderbird’

“Thunderbird” also was hit hard by flak over the target and limped along only a few minutes longer than did “Hellsapoppin.” Apparently, “Thunderbird” took two direct hits on the No. 3 and 4 engines. The right wing was immediately set ablaze by burning oil. There was also fire in the radio room and bomb bay. The pilot, Lieutenant Harold Beasley, hit the fire extinguisher switch. Nothing.

The ball turret gunner, S/Sgt. James L. Branch, looked up at all the fire and knew “Thunderbird” was in serious trouble. He figured it was time to get out. Branch had been hit in the corner of one eye by a piece of shrapnel, and blood covered the eye. He called Beasley over the intercom and asked to come into the fuselage.

After getting out of the turret, Branch grabbed a fire extinguisher and went to work in the radio room and bomb bay but could not extinguish the fires. Beasley rang the bail-out bell and then asked Branch to go to the rear of the plane to see if everyone was out. Branch saw that the tail gunner, S/Sgt. Johnnie Cagle, had bailed out through the tail hatch. He then told the waist gunners to jump from the waist hatch and told the radio operator, T/Sgt. Jay M. Franklin, to “get your ass back there and bail out.”

Franklin started back but passed out in the door of the radio compartment, apparently from lack of oxygen. Branch and the right waist gunner, S/Sgt. Everett L. Creason, picked him up and threw him out, assuming he would come to and open his chute when he fell to where oxygen was adequate. He did. Creason bailed out, and Branch called up to the pilot to tell him everyone else was out and he was leaving. After exiting the aircraft, Branch opened his chute and looked up. He saw “Thunderbird” rise up on its back, turn on it nose, and go straight into the ground.

While all this was going on in the rear of the aircraft, the flight engineer, T/Sgt. Mark L. Schaefer, came down from the top turret and stood behind the pilot and co-pilot to assist them in getting control of the aircraft. He saw Beasley push the control column all the way forward and then pull it all the way back. No response! The controls were shot out. Beasley and the co-pilot, Lieutenant Walter McCain, were getting ready to get out of their seats and snap on their chutes as Schaefer went down to the nose hatch and bailed out.

As the action had begun to develop, the bombardier, 2nd Lt. Mathew Michaels, who was on his first mission, saw puffs of black smoke around the aircraft. He thought to himself, “This must be what they had told us about.” Just then “Thunderbird” took direct flak hits in the right wing. Beasley hit the bail-out bell, which Michaels mistakenly took to be only a warning. While Michaels was waiting for the second bail-out bell to ring, the navigator, 1st Lt. Harry D. Sipe, headed for the nose hatch and bailed out. At that time a fighter appeared alongside the bomber. Lt Michaels fired at him with the side gun, but missed.

“Thunderbird” started spinning downward. A case of .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition pinned Michaels to the top of the nose compartment. He heard glass breaking as his head crunched against one of the windows. A fighter came head-on at “Thunderbird,” blowing away part of the nose with 20mm cannon fire. The next thing Michaels knew, he was floating free of the plane. Either he had been blown out the nose when the 20mm cannon shells hit or was stunned by the explosion and did not remember going out the nose hatch. He was still fairly high up and pulled his ripcord in time to float safely to the ground.

Beasley and McCain must have been locked into the plane as it nosed over and dived downward. Their bodies were discovered by the Germans in the wreckage of “Thunderbird,” which crashed about 20 miles southwest of Bremen. Three planes were left in the low squadron.

‘Sky Wolf II’ Finally Succumbs

Although “Sky Wolf II” had been hit hard on the bomb run and the No. 1 engine was on fire, Stoffel kept her in position over the target. The bombardier, Coppage, toggled the bombs with the rest of the squadron. As soon as the group turned off the target and was just beyond the edge of the flak barrage, more enemy aircraft jumped “Sky Wolf II.” Another 20mm shell hit the nose, throwing plexiglass into Coppage’s face, causing severe wounds. The navigator, 1st Lt. John F. Segrest, Jr., who had also suffered wounds in both legs and his shoulder, told Coppage he needed immediate medical attention and helped him out the nose hatch. Although alive when he left the aircraft, Coppage did not survive.

Segrest then went into the cockpit to help Stoffel fly the plane. They flew along for about five minutes when more fighters came at them. “Sky Wolf II” took a direct 20mm hit that knocked out all the controls. Stoffel pushed the bail-out bell and said to Segrest, “Let’s go.” Both officers went down to the nose hatch and bailed out.

The electrical system to the ball turret was inactive, and the gunner, Sergeant Carl H. Quist, could not rotate around to get out. He remained trapped in the falling aircraft. The tail gunner, Sergeant Mathew C. Medina, had not been heard over the intercom for some time. He apparently was either dead or so badly injured that he could not bail out. Medina also went down with “Sky Wolf II,” which crashed 10 miles south of Aurich, in Ostfriesland, Germany. Two planes were left in the low squadron.

Just Two Planes Left in the Low Squadron

“Rain of Terror” was hit by flak as well as by Me-109s and FW-190s over the target, setting the aircraft afire. The bombs had just dropped when more flak hit the aircraft. The bomb bay doors were still open. The pilot, Lieutenant Robert Walker, managed to keep the plane with the formation in spite of the fire. On the way to the coast, a fighter made a pass over the top of the bomber, wounding the top turret gunner, T/Sgt. Robert F. Flanagan. The tail gunner, S/Sgt. Nick Sandoff, was most likely killed during this attack. The radio operator, T/Sgt. Gust E. Collias, saw him slumped over in the tail.

As “Rain of Terror” continued toward the North Sea, the fires became more intense, and Walker could no longer keep her in the air. The aft crew bailed out, Collias going out through the bomb bay. He did not see the left waist gunner, S/Sgt. Donald J. Snell, in the plane when he bailed out. He assumed Snell, who did not survive, had already gone out the waist door. The ball turret gunner, S/Sgt. Raymond C. Ottman, came up from the turret and went out the waist hatch. He had been hit in the buttocks and back during the fighter attacks.

The togglier, a Sergeant Zedoneck, and the navigator, 1st Lt. Roy W. Scott, bailed out the nose hatch. Zedonek landed in a tree, severely straining his back. German farmers spotted him and turned him over to the military. Scott fell softly to the ground about two miles southwest of Bremen. As “Rain of Terror” continued losing altitude, the pilot and co-pilot finally made a crash-landing on the coast of the North Sea. They both became POWs.

All 401st planes were now gone from the low squadron. Only the 323rd Groups’ spare aircraft, No. 399, “Man-O-War,” flown by the 92nd Bomb Group crew, was left. Pilot Lieutenant Lowell Walker formed up with another squadron for protection. The low squadron was no more.

‘Short Snorter III’ Goes Down at Sea

In the Composite Group, No. 337, “Short Snorter III,” made it through the flak over the target without being hit. On the way out to the coast, she was attacked by fighters which inflicted heavy damage on the aircraft. Still, “Short Snorter III” remained in formation. At 1326 hours, as the aircraft passed three miles east of Emden, “Short Snorter III” took direct flak hits that knocked out the No. 3 engine and set the No. 4 engine afire. The pilot, Lieutenant Nathan Lindsey, feathered the No. 3 engine. Almost immediately afterward, another antiaircraft shell burst into the cockpit, killing both Lindsey and the co-pilot, 2nd Lt. George Slivkoff. More flak hits smashed into the aircraft. “Short Snorter III” began slowly circling downward.

The bombardier, 2nd Lt. Albert Dobsa, was hit in the stomach by one of the flak bursts. The navigator, 2nd Lt. Rocco J. Maiorca, was uninjured. Dobsa, sensing the plane was out of control, went to the cockpit to see what was wrong. He saw both pilots dead in their seats. He looked back into the fuselage and saw crewmen lying on the floor, also apparently dead.

Dobsa knew it was time to bail out and went back into the nose. Maiorca was standing above the nose hatch, hesitating to jump. Dobsa pushed him out the hatch and dropped through after him. Dobsa came down in the shallow water near a beach in the Frisian Islands where he was immediately captured by German troops. Maiorca drifted about a mile out to the sea off the Islands and swam ashore. He was in the water for three hours before he was taken captive.

“Short Snorter III” went on out to sea where she crashed, taking the rest of the crew with her to a cold, watery grave. Only two of the seven 401st planes, Nos. 484 (“Bad Egg”) and 437 (“Frank’s Nightmare”) were still flying. “Frank’s Nightmare” had only six bullet holes in the right stabilizer, and the pilot, Lieutenant Donald Frank, landed her at 1556 hours. “Bad Egg” had one of her tail guns disabled by a flak burst and several holes in the fuselage. She touched down at Bassingbourn at 1615 hours.

The Heavy Toll on the 91st

Of the 21 returning aircraft in the other three squadrons, three sustained heavy damage. The top turret of No. 497 (“Frisco Jinny”) was blown out by the 20mm shell that killed Sergeant Hale. The other two bombers with major damage were from the 323rd Squadron. Number 77 (“Delta Rebel No. 2”) was hit hard; a 20mm shell had exploded in the nose, knocking out most of the glass, damaging the Norden bombsight, and wounding the bombardier, 1st Lt. Robert G. Abb, in the hand. The No. 1 engine was also hit. Number 475 “Stric-Nine,” flown by 1st Lt. Homer C. Briggs, Jr., was raked by 20mm cannon fire as she came off the target. The No. 4 engine and the oxygen system on the plane’s left side were shot out. “Stric-Nine” landed at Hethel to refuel before going on to Bassingbourn.

The remaining 91st planes returned safely to England. The last plane in formation going straight on to Bassingbourn, No. 481 (“Hell’s Angels”) of the 322nd, touched down at 1636 hours. The sky was clear of bombers. The 401st ground crews milled around with looks of disbelief on their faces. Only three of the nine squadron planes that had taken off six and a half hours earlier were now sitting on their hardstands. One of these had aborted over the English Channel and did not make the run.

Fifty 401st crewmen, along with 10 men of the 92nd Group flying in the 401st Squadron, were missing. Eventually, it would be learned that a total of 32 had been killed and 28 survived to become POWs. While accustomed to losses, so many on one mission and all from one squadron had a demoralizing effect on all crewmen of the 91st Bomb Group, flight and ground alike.

Morale was no better over in the 306th Bomb Group at Thurleigh. Ten of the two dozen planes the group had put in the air were shot down. Five of the six planes in the high squadron and three of four in the low squadron were lost. Thirty-four crewmen were killed, and 66 became POWs. Planes of the 369th Squadron of the 306th, flying in the Composite Group, were hit hard by flak and fighters, but none of these bombers went down. During the May 17, 1943, mission to Bremen, 16 of the 107 bombers that reached the target were lost, all from the 91st and 306th Bomb Groups.

Of the 233 91st Group crewmen who returned to Bassingbourn from Germany that day, 42 were later killed in action, while 31 others became POWs. The casualty rate among them was 31.3 percent.

Bleak Future for the Surviving Planes of the 91st

The future for the surviving planes of the 91st Group was even bleaker. Eighteen of the 23 returning B-17s were shot down within a few months. Three were so badly damaged that they were placed in salvage and cannibalized for spare parts. One was declared unfit for combat and transferred to the Aphrodite program to be filled with explosives and sent as a flying bomb to attack the V-1 buzz bomb site at Mimoyecques, France. The plane was blown to bits and missed her target. A total of 80 crewmen flying on the last missions of these bombers were killed in action, and 92 became prisoners of war. Another 19 crewmen were shot down but evaded capture.

Hollywood movie director William Wyler had been at Bassingbourn for several weeks filming combat action for a documentary dealing with VIII Bomber Command. His intention was to base the documentary on the plane and crew to complete 25 missions, the required number for a return Stateside. The Army planned to have the crew fly its plane back to the States for a public relations tour to encourage sales of war bonds. The plane Wyler had selected and had been filming was “Invasion 2nd,” but the crew and Captain Oscar D. O’Neill were lost on the pilot’s 24th mission.

With the loss of “Invasion 2nd” and Captain O’Neill’s crew, Wyler had to select another plane and crew. He picked No. 485, “Memphis Belle,” and Captain Robert K. Morgan’s crew from the 324th Squadron. “Memphis Belle” flew her final mission on May 19, with 1st Lt. Clayton L. Anderson’s crew. Captain Morgan’s crew had completed its 25th mission two days earlier.

“Memphis Belle” was ordered to return to the U.S., and Captain Morgan and his crew departed with her on June 13. “Memphis Belle” was the only plane that flew the May 17 mission to Bremen to survive the war. She was also one of the very few B-17s that flew combat to escape the recycler after the war. “Memphis Belle” eventually came to reside on public display in Memphis, Tenn.

The party scheduled for the evening of May 17 went on as scheduled. Approximately 200 officers and 150 service and civilian guests congregated in No. 1 Mess. The events of the day cast an ominous gloom over the evening, the sense of despair heightened by the presence of girls whose dates were among the missing. A few found other escorts, but most simply stood around watching the dancing until the trucks took them back to their villages.

Late in the evening, many of the officers who had indulged too freely of the alcohol became unruly, creating a considerable disturbance. This behavior was understandable, given the pent-up frustration of losing so many friends and knowing that very likely they would be next. Eventually order was restored, the men retired to their billets, and the girls returned to their homes.

There would be other bad missions, other parties, other dates, and other missing escorts. The losses went on, the parties went on, the war went on. There were 271 missions yet to be flown.

Lowell L. Getz is professor emeritus of ecology, ethology, and evolution at the University of Illinois. He is also a retired U.S. Army colonel.

One of the best recounts of the Bremen raid (or any mission of the USAAF for that matter) that I have read. Just the right amount of factual information and personal anecdotes. The names / identities of the individual aircraft connecting with the names of various crewmen made this a personal narrative and extremely interesting. Very well written Mr. Getz (or Colonel Lowell L Getz, ret.)

PS: Have pictures of Memphis Belle (owned by The Collings Foundation) but just not posted on the internet.

My dad’s uncle was the co pilot on hellsapoppin, he survived being a POW and made it home. Was like a grand parent to me, would never talk about the war to anyone. He died relatively young, I think being so wounded and being a pow took 25 years off his life. Kindest man I ever met. He is missed….

Staggering ignorance to claim that 117 heavy bombers over the continent was the largest number to date, when the British had put 1,047 bombers onto Cologne the previous year (30-31 May 1942). Myopic “history”, that’s for sure. But it is worse than that – the previous year (25-26 June), the RAF sent 960 bombers to Bremen, with 700 bombing it, most with bomb loads much greater than the “heavy” B17s. 117 bombers is pitiful in comparison. I appreciate that Professor Getz is not a historian – but come on! Other than that, it is a pretty reasonable account of VIII AF mission number 52 – except that 115 bombers were despatched, not 117. Mission 52 put the largest number of VIII AF heavy bombers over the continent up to that date.

If you read the article, it was the VIII Bomber Command that put 117 heavy bombers over the continent as the largest number of the VIII Bomber Command to date. It specifically said VIII Bomber Command (U.S.). The article said nothing about the RAF bombings, specifically being left out because it was only talking about U.S. daylight bombing.

Side note: The bombing was not all that accurate. Despite claims as to the effectiveness of the Norton bomb sight, information gathered after the war indicated that fewer than 15% of the bombs came within 1000 yards of the intended target. Consequently, saturation bombing was the preferred method of attack but also resulted in higher casualties among the attacking forces from flak and interceptors.